From Discussions VOL. 2 NO. 1Individualized Behavioral and Image Analysis of Response Time, Accuracy, and Social Cognitive Load During Social Judgments in Adolescents

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

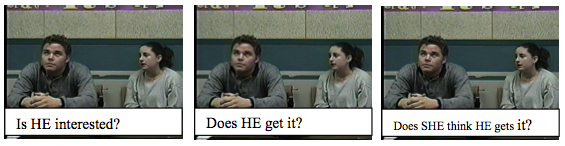

AbstractFunctional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become an invaluable tool in understanding the relationship between brain and behavior. This technique has become particularly important in the study of human social cognition. The current study focuses on the social cognitive judgment skills of late adolescents (ages 18 -21), and seeks to investigate four specific aims. These aims include the following: 1) To characterize the relationship of accuracy of responses and reaction time while making social judgments; 2) To describe the relationship between response accuracy and social cognitive load; 3) To identify the relationship between questions of increasing social cognitive demand and reaction time; and 4) to identify the interaction between response time, accuracy, and increasing social cognitive load. A secondary aim of this study is to complete an individualized functional imaging analysis taking into consideration each participants' accuracy and reaction time. This analysis will provide further insight into the brain-behavior relationship in human social cognitive function. Behavioral and imaging results of the present study will be reviewed. INTRODUCTIONSocial cognitive skills, such as the detection of sarcasm, the expression of humility, and the sharing of the conversational burden, are vital for successful social interactions with peers, especially during adolescence when individuals are faced with increasingly complex social interaction (Turksra 2000). The use of functional imaging technology has allowed investigators to examine the neural mechanisms responsible for social cognitive skills (Saxe 2006). Some of the brain regions identified as important for social cognitive behaviors include the superior temporal gyrus, anterior cingulate, fusiform gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, and inferior parietal lobe (Ciccia, et al. 2006). The present study investigates the behavioral effects of reaction time, accuracy, and level of social cognitive load on the functional imaging methodology currently used by Ciccia (2006) to study brain activation patterns during social cognitive judgments in adolescents. A secondary aim of this study focused on using the results of the behavioral analysis to customize the functional imaging analysis. Tailoring the functional imaging analysis to each participant's social decision reaction time will allow for a more valid investigation of the imaging results. METHODSParticipantsAll participants in this study met the following inclusion criteria: 1) No history of neurological disease or disorder (including acquired brain injury); 2) No history of learning or reading disability or gifted states; 3) No history of claustrophobia; and 4) No metal in their body (e.g., pacemaker wiring). The participants ranged in age from 18 to 21 years, with a mean age of 19 years, and included four male and four female participants. A total of fourteen participants completed the study; however, only data from eight of these participants could be analyzed. Four participants could not complete the study because of illness at the time of the scan, one participant was removed from data analysis because of clinical findings discovered when the file was reviewed by a Radiologist, and another participant was removed from data analysis because of equipment malfunction during the functional imaging protocol. Imaging Tasks and Behavioral Procedure Tasks:Participants were shown videos of different social conversation interactions that occurred between adolescent actors (Turkstra, 2000). Conversations focused on topics that were identified by adolescents as appropriate and likely to be brought up in normal conversation. These included topics such as after school activities, classroom performance, friendships, and dating. Social conversational skills that were depicted in these interactions included detection of sarcasm, expression of humility, and sharing conversational burden. After watching each video, participants were asked to make a series of social judgments of increasing difficulty based on the interactions just viewed (Figure 1). The first social judgment, requiring minimal social cognitive demand, was, "Is X interested?" (X referring to a specific actor in the video clip). The participants were then shown the same clip a second time and asked, 'Does X get it [the meaning]?' This question required a moderate amount of cognitive demand. After a final showing of the video clip, the participants were asked the high-level cognitive demand question, 'Does Y think that X gets it [the meaning]?' where Y refers to the second actor in the conversation. Figure 1: This figure shows video clips from the paradigm with the three questions used in the study. In this video, the female character is trying to elicit sympathy and compassion from the male character by telling him that her dog died this morning. The male character is not paying much attention to her or her story. The video was shown three times to each participant, with one question being presented in this order after each video clip.

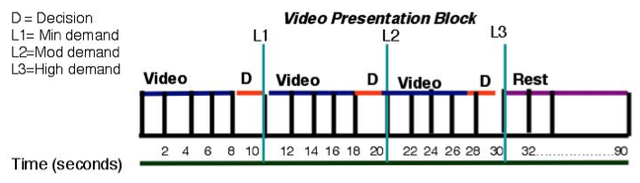

A total of three blocks, with five video vignettes in each, were shown to the participants. Each of these videos was shown three times within a block. Each video and each block was followed by a period of rest of either four or six seconds where the participant was presented with a blank screen. There was a sixteen second break following the last question in each block. Figure 2 depicts the paradigm design for each block, including rests. Each video clip, including decision making time, equaled a total of ten seconds. Following each clip, the participants had a three second window to give a response, although it was possible for them to give a response even after the next video had started. Each block took a total of 3:06 minutes. Figure 2: Video Presentation Block, an example of the video design shown in this experiment. The participants were shown a video example of a common social conversation. After viewing the video, the participants were asked to make a series of social judgments, which were presented in an order of increasing difficulty. The participants saw each video clip three times, each time followed by a different question. There were five individual video clips in each block.

Procedure:Informed consent was obtained and a practice session was completed before the participants entered the scanner. The practice session lasted one hour and consisted of reviewing social rules and practicing the video paradigm on a computer. The review of social rules included questions such as: "What makes a good/ bad communication partner? What makes a conversation go well? How do you know?" The functional imaging protocol took place at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and was completed within 48 hours of the practice session. Prior to beginning the functional imaging protocol, the video paradigm was practiced outside the scanner for a second time and the imaging technician answered any questions the participant's may have had about the scanner. Aside from watching the video paradigm, the participants were also required to make behavioral responses according to their social judgments. Participant responses were collected using 5DT virtual reality data gloves. The gloves were placed over the hands of the participants, who would then make minimal hand movements to register their response. The participants were instructed to move their left hand to indicate "no" and their right hand to indicate "yes". The participants were given the opportunity to practice this response pattern, with the gloves on, prior to completing the video protocol in the scanner and again between video block presentations. To ensure the comfort and safety of participants during the fMRI protocol, time in the scanner was limited to one hour and a foam pad was placed under each persons' head and knees. Additionally, participants were in constant contact with the researchers via an audio system that allowed researchers to hear the participants at all times. Participants were also given a "panic button" which would alert the research staff of any type of emergency. Each participant removed any metal from their bodies (e.g. earrings) prior to entering the scanning area.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Psychology |