Emotion and Politics: How Strengths of Mind Relate to Political Attitudes in the United States

By

2021, Vol. 13 No. 12 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

AbstractPolitical polarization has been an increasingly salient point of discussion since the 2016 presidential campaign, the election of Donald Trump, and into today. Beyond emphasizing partisan and issue-based divides, scholars have identified emotion-based roots of polarization. With more cognitive and emotional aspects of social behavior being considered in empirical frameworks, contributions from psychology have become of paramount importance. The present study employs measures of variables that emphasize self-awareness and openness to opposing viewpoints, like intellectual humility. Research to date analyzing these variables has been limited to few previous studies. A mixed methods survey approach to measure growth mindset, intellectual humility, and students’ political attitudes was carried out here. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) analyses identified limited connections between growth mindset and intellectual humility. Further investigation among a broader sample is needed to draw more concise connections between the role that psychological traits, like personality, play in the strength of political attitudes.

INTRODUCTIONPolitical polarization in the United States has been an increasingly salient point of inquiry for pundits and academics since the 2016 presidential election—and presidency of Donald J. Trump that followed (Bansal and Weinschenk, 2020; Weeks et al., 2019). Moving beyond emphasizing strictly partisan and issue-based divides, scholars have identified more affective bases of polarization (Iyengar et al., 2012; Mason, 2018). With more individual cognitive and emotional aspects of social behavior being considered in emerging theoretical and empirical frameworks, contributions from the field of psychology have become of paramount importance. However, the existing literature featuring collaboration across disciplines have yet to reach their full potential. Moreover, comprehensive measures of variables that emphasize self-awareness and openness to opposing viewpoints, like intellectual humility, have been limited to only a handful of previous studies (Porter and Schumann, 2018).For decades, social and personality psychologists have looked to study predictors of achievement by going beyond the consideration of factors such as luck and circumstance (Duckworth et al., 2019). These same variables, however, have potential to be extended into the political and public spheres. The present study seeks to identify relationships between political attitudes and opinions—and two psychological strengths of mind often found in achievement research: growth mindset (Dweck, 2006) and intellectual humility (Hodge et al., 2020; Porter and Schumann, 2018). This inquiry may deepen understandings concerning the extent to which political attitudes and “non-cognitive” factors are related. Because lacking openness to disagreement and lowered respect for opinions that may be incongruent with one’s own are identified as key consequences of affective polarization (Huddy and Yair, 2017; Marcus et al, 2007), those same characteristics are key in the measurement of one’s intellectual humility. Thus, furthering the notion that the two may be correlates of one another. Those same factors that have yielded positive results in areas of human flourishing may be equally salient in healing political divides and contribute to a foundation for societal flourishing. Three research questions were posed in the present study:

The framework in this research strives to identify relationships between intellectual humility and growth mindset—as well as attempts to extend those connections to attitudes on controversial political issues like gun control and political ideology. A mixed methods approach surveying a total of 144 participants was employed. 138 students completed an online survey that measured these items. Additionally, six (6) qualitative interviews were conducted in an attempt to elaborate on these research questions and make connections to collected quantitative data. REVIEW OF LITERATURERhetoric surrounding the 2020 presidential election has provided a snapshot of the larger, troubling picture that is a deeply divided United States body politic (Pew Research Center, 2020). From rampant disinformation on social media, to increased social sorting (Mason, 2016), there is mounting evidence demonstrating that Americans are becoming more polarized at an alarming rate (Pew Research Center, 2014; Pew Research, 2020; Westfall et al., 2015). To date, much attention has been directed to the role that mass communication and misinformation relate to polarization (Schaewitz et al., 2020; Weeks et al., 2019). While media impact is a necessary cog in understanding the machine that is polarization as a whole, this research seeks to extend beyond exploring mediums for communication as a variable—and tap into the psychological roots of division itself. In recent years, partisans have moved beyond being strictly polarized over issues and policy (Iyengar et al., 2012, pp. 405-406; Mason, 2018, p. 868). Contrary to Converse’s theories of ideological innocence (as cited in Clawson and Oxley, 2017, pp. 140-148), polarization has stemmed past the perceptions of polarized political elites, extending to more of a polarized citizenry (Huddy and Yair, 2020, p. 2). Mason (2018) notes that distain between liberal and conservative-minded individuals may go past matters of opinions (p. 868). To this end, scholars have gone to consider affective, or emotional, bases of polarization (Groenendyk and Banks, 2014; Iyengaret al., 2012; Mason, 2016; Mason, 2018; Marcus et al., 2007; Weeks 2015). The study of affect’s role in politics specifically aims to investigate the way emotions interact with political cognitions (Marcus et al., 2007). Existing literature has identified a still-growing wealth of knowledge and theory studying the structural link between political thought and emotion, such as causal factors, and other relationships (pp. 2-5; Young, 2020). Several origins of affective polarization have also been distinguished. Selective exposure to media that confirms one’s own beliefs and hostility toward media that portrays opinions counter to one’s own (Selective Exposure Theory and Hostile Media Effect, respectively) are two prominent roots of affective polarization on an interactive level (Feldman, 2017; Kaye and Johnson, 2016; Weeks et al., 2019). Other contributors include perceived dissimilarity between partisans on racial, economic, ethnic, gender, and geographical lines—as well as psychological investment in choosing candidates (Huddy and Yair, 2020, p. 2). Taken together, the “us” versus “them” mentality drives the growth of affective divisions, adding to the notion that efforts to decrease hostility between groups as opposed to seeking policy agreement between parties on issues may be a more effective tool in mitigating affective polarization as a whole (p. 3). A connection between respect for others’ beliefs via cultivating intellectual humility seems to be a promising method for achieving this partial remedy. As a subdomain of general humility, intellectual humility’s conceptual definition is not widely agreed upon. Past studies have attempted to define the trait as having awareness of the limitations of one’s knowledge (McElroy et al., 2014), the ability to recognize one’s beliefs as potentially false or incomplete (Leary et al., 2017), or simply having acknowledging the presence of other perspectives (Krumrei-Manusco and Rouse, 2016). To date, only two studies exist that measure intellectual humility in the context of American politics (Hodge et al., 2020; Porter and Schumann, 2018). Porter and Schumann (2018) conceptualize intellectual humility by inviting components of the previously stated definitions: “. . . awareness, and . . . a willingness to appreciate others’ intellectual strengths” (p. 140). This study will employ an operationalization of this definition due to the inclusion of both awareness of personal knowledge and others’ viewpoints, thus solidifying the connection to the aforementioned effects and roots of affective polarization. At present, only one existing study in the psychological literature measures growth mindset in relation to intellectual humility (Porter and Schumann, 2018). Growth mindset, first pioneered by Carol Dweck (1998, 2006), is commonly investigated in the realm of educational and personality psychology under the umbrellaed belief that individuals have the potential to change their mindset about personal abilities and efficacy (p. 14). This includes, but is not limited to, a belief that intelligence is something malleable; that one can fundamentally change the kind of person they are; and belief in one’s own—or others’ abilities—as opposed to a fixed mindset (e.g. “I am not a math person” (fixed mindset) and “If I work hard, I can understand math better” (growth mindset)) (pp. 13-14). Additionally, having a growth mindset involves a specific personal monitoring of one’s own attention, memory, and judgement (i.e. being self-aware)—with the motivation that the end goal(s) concern a strife for growth, not perfection (p. 5). Both intellectual humility and growth mindset require some level of self-awareness. Porter and Schumann (2018) discovered that growth mindset extends to influence intellectual humility, as it is also impacted by both external and internal factors (p. 142). Moreover, their findings elaborate further by demonstrating a predictive relationship between growth mindset and intellectual humility (p. 157). That is, those who believed that traits and intelligence are malleable also demonstrated more openness to opposing views. Both studies, however, do not address the deeper psychological connections between mindsets and humility (i.e. metacognitive monitoring). Metacognition, or thinking about one’s thinking, is a reflective process defined as an awareness and understanding of one’s own cognitive processes (Feldman, 2017). A growing, but scarce, body of research has investigated metacognition as a variable alongside political beliefs (Rollwage, Dolan, and Fleming, 2018). The same literature involving political contexts identify metacognitive error as a key component of those who are persevering in their beliefs, even in the face of new information (p. 4014). On the whole, levels of awareness regarding the self should be understood in light of contemporary socio-political cleavages. At present, research investigating the relationship between intellectual humility and growth mindset is still largely unexplored territory. Moreover, little is known about each variable’s connection to attitudes of both controversial issues and favorability ratings of political leaders. The current survey seeks to address this disparity via a mixed methods approach. Theoretical Framework Diagrams

Public SignificanceIn a new era of increasing media availability and heated political rhetoric, many have begun searching for novel methods to mitigate hostility and disinformation in American politics. This study aims to add to the existing literature by investigating personal psychological attributes as they relate to political attitudes and beliefs. Metacognition is known to be involved in processes of intellectual humility and growth mindset, both of which have been empirically demonstrated as significant for understanding processes of affective polarization. Thus, further study about cultivating self-awareness (i.e. strengths of mind: intellectual humility, growth mindset, etc.) may prove to be a pivotal component of partly remedying polarization of the United States body politic. METHODOLOGYAs a result of the gaps in existing research regarding specific psychological attributes and political polarization in the United States, the following measures were designed and executed. ParticipantsThis study used convenience sampling, a non-probability type of sample, as the researcher had access to the population. A goal of 100 respondents was set for this survey. Following recruitment, 144 respondents (N=144) elected to participate, exceeding the study’s goal. 138 respondents volunteered to complete an online survey. All respondents were undergraduate students at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. with graduation years ranging from 2020 to 2024 and ages ranging from 18 to 39 years old. Additionally, six respondents (6) that did not participate in the online survey agreed to individual qualitative interviews. These participants ranged in graduation years from 2021 to 2023 and were female. ProcedureRecruitment was conducted through social media outreach in student group pages and email correspondence to university students. Text of the recruitment and procedure can be found in the appendices of this report. Participants who took part in individual interviews were also recruited from online social media groups affiliated with The George Washington University. These in-depth measures sought to elaborate on data collected from the quantitative measures. MeasuresQuantitative Measures. There were five sections to the present study: political ideology and identification; intellectual humility, mindsets, favorability of political leaders, and political participation in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Measures of political ideology were developed from Pew Research Center’s (2014) Ideological Consistency Scale. The original scale yielded sound internal consistency (ɑ = .72). A version of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale (Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse, 2016) was used to measure participants’ intellectual humility on a Five-Point Likert scale. This original scale yielded high internal consistency (ɑ = .88). Lastly, measures for mindset (fixed versus growth) were adapted from Dweck (1998, 2006, 2019) and De Castella and Byrne (2015). The mindset scale demonstrated high internal consistency (ɑ = .93). All questions included in this survey were carefully considered for priming effects, order effects, non-attitudes, and wording and context of questions (Asher, 2017, pp. 43-106). Qualitative Measures. Individual interviews adapted from the online survey questions were also conducted for this report. Six interviews were held via telephone and recorded with consent of the respondent. Please see the appendices of this document for the interview question text. Questions for this section were designed to yield open-ended responses from participants. Additionally, interviewer skills and demeanor were considered in careful efforts to maintain objectivity, permit space for elaboration and explanation where necessary, and consistency across participants (Asher, 2017, pp. 144- 152). ANALYSIS OF THE FINDINGSA series of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship(s) that might occur between intellectual humility and growth mindset—and attitudes toward controversial political issues in undergraduate students. Additionally, those same strengths of mind were measured alongside favorability of political leaders. Descriptive measures and frequencies are also displayed to show participant responses and demographic information. Descriptive StatisticsThe descriptions in this section are representative of the quantitative online survey only. Age and Graduation YearThe sample in the current survey included a variety of students from graduation years ranging from 2020 to 2024. The students ranged in age from 18 to 39 years. Table 1. Expected Graduation Year

Table 2. Participant Ages

Political Ideology and IdentificationTable 3 describes respondents’ political party identification. 52.2% (72) self- identified as “strong democrat,” 21% (29) as “weak democrat,” 17.4% (24) as “independent,” 5.8% (8) as “weak republican,” and 3.6% (5) as “strong republican.” Table 3. Party Identification

Of these respondents, a majority (67.4%) described their party identification as “moderately important,” “very important,” or “extremely important.” In contrast, a combined 32.6% of participants indicated that their political party identification was only “slightly important” or “not at all important.” (Table 4). Table 4. Importance of Party Identification

When asked to self-report their political ideology, the sample was skewed heavily liberal, with a combined 85.5% of respondents describing themselves as “somewhat liberal,” “mostly liberal,” or “very liberal.” 6.5% (9) respondents described their political ideology as “moderate,” and a combined 7.9% identified as “somewhat conservative,” “mostly conservative,” and “very conservative.” (Table 5). These findings held consistent on the basis of those who identified as a democrat also described their political ideology as varying degrees of “liberal.” Table 5. Self-Reported Political Ideology

Attitudes Toward Controversial IssuesWhen asked for their attitude of the “Black Lives Matter” movement based upon self-knowledge and/ or media representations, a majority of respondents indicated support for the organization (88.4% “support” or “strongly support”) 7.2% (10) respondents said they either “do not support” or “strongly do not support” the “Black Lives Matter” movement (Table 6). These findings were fairly consistent with self-reported ratios of democrats and republicans in the sample. Table 6. Support of “Black Lives Matter”

On the matter of supporting a ban on assault rifles, 82.6% (114) of respondents indicated that they are “for” legislation that would act to ban assault rifles. 17.4% (24) respondents said that they would be “against” a law that would ban assault rifles (Table 7). Table 7. Support for a Ban on Assault Rifles

Favorability of Political LeadersAn overwhelming majority of students (93.5%) in this sample declared an “unfavorable” opinion toward both President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence. 8 respondents (5.8%) said they had a “favorable” opinion toward the current President and Vice President (Table 8). Table 8. Donald Trump and Mike Pence Favorability

As shown in table 9, students’ favorability ratings of President-elect Joe Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris differed significantly. 72.5% (100) respondents said they had a “favorable” opinion toward President-elect Biden and Vice President-elect Harris, whereas 26.1% (36) said they had an “unfavorable” opinion of Biden and Harris. Table 9. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris Favorability

Voter ParticipationA majority of respondents in the sample voted in the 2020 United States Primary Elections earlier this year (71.7%). 27.5% (38) did not vote in the primary election—and one (1) non-response was measured (Table 10). Voter participation improved in the 2020 United States General Election with 93.5% (129) of respondents indicating that they voted on November 3, 2020. 5.8% (8) did not vote and one non-response was measured (Table 11). When asked which ticket they supported, a majority of respondents said they voted for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris in the November 3, 2020 election: 87% (120). 5.8% (8) of respondents supported President Trump and Vice President Pence and 5.1% (7) of voters in the current sample supported a third-party candidate. Three (3) non-responses were recorded (Table 12). Table 10. 2020 U.S. Primary Election Participation

Table 11. 2020 U.S. General Election Participation

Table 12. 2020 General Election Candidate Support

In light of the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, respondents were asked which method of voting they chose in the 2020 election. 67.4% (93) of students in this sample voted early or by mail. 10.1% (14) voted in person on election day and 16.7% (23) said they voted early in person. Eight (8) non-responses were recorded (Table 13). Table 13. Voting Method

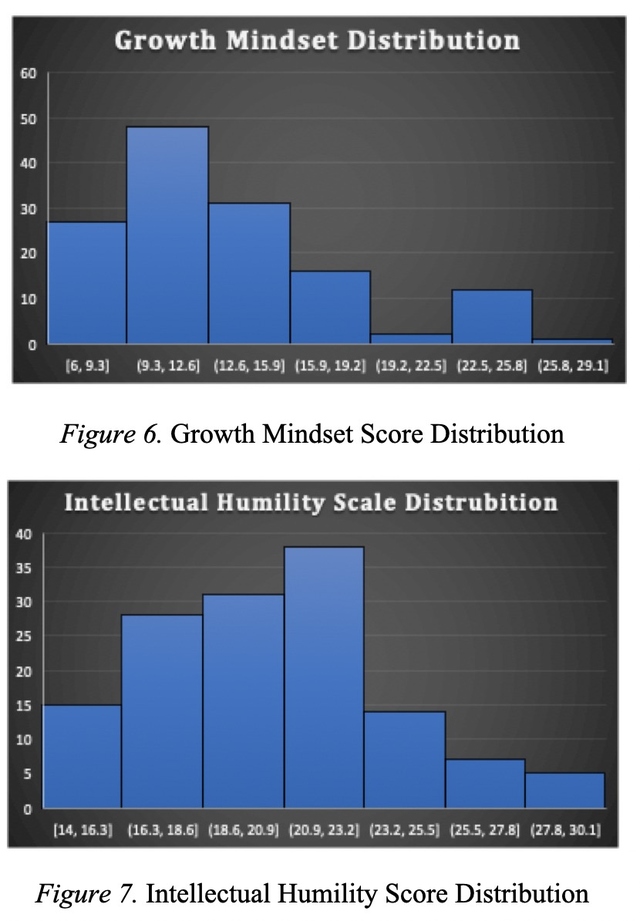

Psychological AttributesTwo measures were employed to measure intellectual humility and growth mindset in this sample. Participants’ responses were reverse scored to determine their individual growth mindset and intellectual humility scores. Those who scored higher points were determined to have greater strength in that respective category and vise versa. The scores for growth mindset, as shown in Figure 6, were not normally distributed. Intellectual humility scores, as shown in Figure 7, however, were more normally distributed. It is worth noting that these measures were only adaptations of surveys deployed by earlier research and were not exact replications and further research is needed to more accurately gauge these attributes and their validity. Scores on both the growth mindset and intellectual humility scales are shown in Tables 15 and 16, respectively. Scores ranged from 6.00 points to 26.00 points on the growth mindset scale with a majority of scores falling between 6.00 and 15.00 points. Intellectual humility scores ranged from 14.00 points to 30.00 points with a majority of scores falling between 18.00 and 24.00 points. Analytical statistics were applied to determine the relationship(s) that may exist between these variables. Table 15. Growth Mindset Scores

Table 16. Intellectual Humility Scores

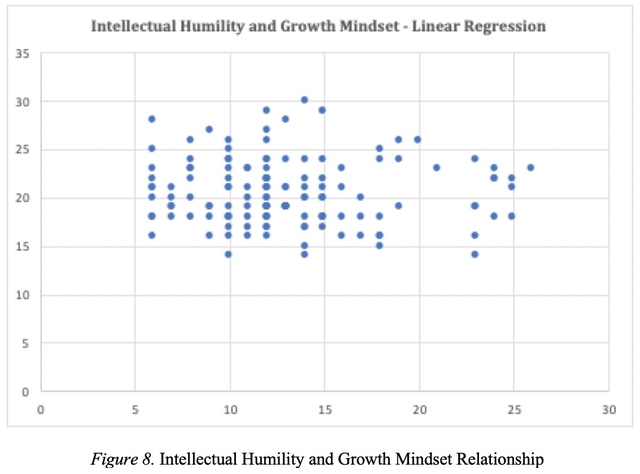

Analytical StatisticsPreliminary Analysis: Growth Mindset and Intellectual HumilityAn ordinary least squares regression analysis showed an insignificant predictive relationship between growth mindset and intellectual humility, β = +0.031, F (1, 136) = 0.130, p > .001, (R2= +0.00096). This finding was not consistent with previous studies in terms of the strength between two variable’s relationship (Porter and Schumann, 2018, p. 149). It is worth noting that this survey was not a replication of previous research, nor did the present survey employ identical measures of mindset or humility as previous research. Future research should develop more comprehensive measures for these variables to demonstrate a sound relationship. Individual scores for growth mindset and intellectual humility were analyzed in correspondents with the present study’s research questions. Full tables for these statistical analyses (regression and ANOVA) are available in the appendices of this report. Research Question 1: How does intellectual humility relate to college students’ attitudes toward controversial topics?A weak predictive relationship was found between those who support the “Black Lives Matter” movement and Intellectual Humility scores, β = +0.100, F (1, 135) = 1.368, p = .244, (R2 = +0.0100). Similarly, a weak relationship existed between those who support legislation that bans assault rifles and Intellectual Humility scores, β = +0.124, F (1, 135) = 2.09, p = 0.215, (R2 = +0.0153). For more detailed statistical tables, please see the appendices of this report. It is essential to note that these statistics do not yield significant findings and should not be taken into generalizable accounts. Research Question 2: How do individual mindsets relate to college students’ attitudes toward controversial topics?A weak predictive relationship was found between those who support the “Black Lives Matter” movement and Growth Mindset scores, β = +0.084, F (1, 135) = .949, p = - 0.417, (R2 = +0.0069). A slightly stronger, but still weak, relationship was discovered between those who favor legislation banning assault rifles and Growth Mindset scores, β =+0.107, F (1, 135) = 1.549, p = 0.215, (R2 = +0.0113). For detailed tables, see appendices. Due to the weak nature of the relationships found in this section, it would be premature to make any generalizations without conducting further study. Research Question 3: Is there a relationship between growth mindset or intellectual humility and favorability of political leaders?With regard to favorability of political leaders, specifically favorability of President Trump and Vice President Pence, a weak relationship was found with regard to Intellectual Humility scores, β = +0.022, F (1, 135) = 0.068, p = 0.79, (R2 = +0.0005). Similarly, a relationship between intellectual humility and support for President-elect Biden and Vice President-elect Harris was uncovered, β = +0.012, F (1, 135) = 0.048, p = 0.83, (R2 =+0.00035). Interestingly, those who indicated a favorable opinion of Donald Trump and Mike Pence yielded a slightly higher correlation in intellectual humility than those who held favorable opinions of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. Growth mindset scores were also analyzed alongside these same favorability ratings of political leaders. While the relationship is weak and not statistically significant, respondents scoring higher in Growth Mindset were found slightly more supportive of Donald Trump and Mike Pence, β = +0.044, F (1, 135) = 0.26, p = 0.611, (R2 = +0.0019). A similar relationship was found between favorability ratings of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris and Growth Mindset, β = +0.023, F (1, 135) = 0.071, p = 0.79, (R2 = +0.00053). Again, due to the nature of this sample being relatively small in the context of the American electorate, skewed heavily liberal, and the limited measures employed in this investigation, generalizations regarding any of the findings reported herein would be premature to take beyond this report. That said, more comprehensive research is needed to (a) investigate the relationship between growth mindset and intellectual humility further via more comprehensive measures and (b) apply those findings to political attitudes and opinions of the public. In an effort to elaborate beyond quantitative data and statistics, a series of personal telephone interviews were also analyzed. Qualitative Interview AnalysisSix (6) individual telephone interviews were conducted in addition to the quantitative survey given to the previously reported 138 participants. Due to the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, these interviews were not held in person. Questions from the earlier survey were adapted to allow respondents to provide detailed, open-ended responses, and engage in a conversation with the researcher (Asher, 2017, p. 144). Core themes of those conversations appear here: Political Ideology and IdentificationAll respondents identified themselves as either “moderate,” “slightly liberal,” or plainly “liberal” when asked how they describe their political ideology. Interestingly, respondents, while eventually identifying with the democratic party, were hesitant to express commitment to a political party citing skepticism of the party system and party leadership. To this end, all six persons said their party identity did not contribute much—or at all—to their personal identity. Additionally, those interviewed said they were able to distinguish their personal values from their political attitudes on matters, like religion. Favorability of Political LeadersAll respondents, when asked to elaborate on their opinion of political leaders, cited personal attributes rather than that of policy or substance. Responses given about Mike Pence and Joe Biden specifically led respondents to elaborate on their opinions about policy after the fact. For example, “Mike Pence is a typical conservative,” citing his public views on abortion or same-sex marriage—or ties to the “republican establishment.” To this end, those who expressed high favorability of President-elect Biden cited in large part “his competence” and “knowledge” of how the government works, as well as Biden’s “. . . ability to get things done.” Interestingly, the question about Donald Trump alone provoked a noticeably heightened emotionally based response from those being interviewed (e.g. dislike of personal qualities, personality versus policy, etc.) These same respondents’ opinions of Kamala Harris, Mike Pence, and Joe Biden seemed to not reach the same level of interest or strong opinion. This falls in line with Mason’s (2018) notion of “ideologues without issues” concerning affective polarization (pp. 866-867). Lastly, participants in these interviews explained a lack of awareness about Vice President-elect Harris’ past political history and expressed interest to “learn more about Kamala.” Psychological AttributesOpen ended questions posed to respondents about both growth mindset and intellectual humility yielded a variety of responses. Four of the six participants said they do not actively seek out information in either social or traditional media that contradicts their own personal opinions or offers another perspective. All, however, did express a willingness to” hear out” those with opposing views. These responses fall in line with core aspects of intellectual humility (i.e. openness to opposition or perspectives). Insight gained from these discussions suggest value in a mixed methods research approach moving forward in the study of affective bases of polarization and political opinions. Participants expressed a developmental theme regarding their mindsets. Two participants elaborated on their “growth mindsets,” placing emphasis on growth over time. Additionally, the respondents said that with greater education and/or completed courses, they noticed changes in their beliefs about intelligence, personal abilities, and self-efficacy. DISCUSSIONIn exploring the relationships between growth mindset and intellectual humility a weak predictive relationship was found. While not a replication of previous research, this study sought to elaborate further on the role that personal psychological characteristics play in the arena of political polarization. Additionally, there were varying degrees of weak relationships found between both intellectual humility, growth mindset and attitudes toward controversial topics like “Black Lives Matter” and indicators of support for legislation that would effectively ban assault rifles. This work is an important start of an already growing body of literature that is seeking remedies for uncivil discourse and division in American society, particularly following the highly contentious 2020 United States Presidential Election. Limitations in this report are wide, including, but not limited to a relatively small sample size (in proportion to the U.S. college student population), and a liberal skew in self- reported political ideology. Moreover, the insignificant statistical findings in the current investigation suggests much room for improvements in measurement and analysis in future research. Moving forward, a more comprehensive survey should be developed and conducted with a wider, more diverse sample. Mixed methods design approaches may prove to be valuable in evaluating these variables—as well as others that contribute to affective polarization due to the elaborative insight they provide as opposed to quantitative findings alone. Additionally, experimental designs should be considered for intellectual humility and mindset in the context of social media interactions to identify causal relationships. The incorporation of longitudinal methods to track the development of intellectual humility, mindset and political attitudes (socialization) over periods of time in a social media age may also prove to be valuable. In 2020, the United States finds itself at a unique point in time unlike ever before. From unprecedented economic tragedy, severe illness, and over 300,000 deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic—to increasing patterns of hostility and ideological echo-chambers in communities and on social media—the quest for ways to bring the nation back to core strivings of growth and new shared prosperity is vast. As more insights emerge about the functioning of the human mind, continued advancements in technology, and how our society is evolving to incorporate a changing world into daily life, that quest may very well begin with exploring those core individual competencies of mind. The mind is hard-wired with blind spots (Tarvis and Aronson, 2007). Blind spots in judgement, information processing, memory, and self-justification. And much like many of us aim to be as aware as possible of blind spots on the road, perhaps cultivating awareness and becoming cognizant of personal biases are just a few of many ways forward in bringing America back to itself. ReferencesAsher, H. (2017). Polling and the Public: What Every Citizen Should Know (9th ed.). CQ Press. Bansal, Gaurav and Weinschenk, Aaron, "Something Real about Fake News: The Role of Polarization and Mindfulness" (2020). AMCIS 2020 Proceedings. 8. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/social_computing/social_computing/8 Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (2017). Public Opinion: Democratic Ideals, Democratic Practice (3rd ed.). Sage Publication. De Castella, K., & Byrne, D. (2015). My intelligence may be more malleable than yours: The Revised Implicit Theories of Intelligence (Self-Theory) Scale is a better predictor of achievement, motivation, and student disengagement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30, 245–267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0244-y Duckworth, A. L., Quirk, A., Gallop, R., Hoyle, R. H., Kelly, D. R., & Matthews, M. D. (2019, December 16). Cognitive and noncognitive predictors of success. Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 116(52), 23499–23504. 10.1073/pnas.1910510116 Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballantine Books. Dweck, C. S., & Mueller, C. M. (1998). Praise for Intelligence Can Undermine Children's Motivation and Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33-52. Feldman, R. S. (2017). Essentials of Understanding Psychology (12th ed.). McGraw Hill Education. Groenendyk, E. W., & Banks, A. J. (2014). Emotional Rescue: How Affect Helps Partisans Overcome Collective Action Problems. Political Psychology, 35(3), 359-378. 10.1111/pops.12045 Hodge, A. S., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, D. E., & McElroy-Heltzel, S. E. (2020, April 16). Political humility: engaging others with different political perspectives. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1-10. 10.1080/17439760.2020.1752784 Huddy, L., & Yair, O. (2020). Reducing Affective Polarization: Warm Group Relations or Policy Compromise? Political Psychology, 0(0), 1-19. 10.1111/pops.12699 Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012, Fall). Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405-431. 10.1093/poq/nfs038 James, W. (1907, March 1). The energies of men. Science, 25, 321–33 Kaye, B. K., & Johnson, T. J. (2016). Across the Great Divide: How Partisanship and Perceptions of Media Bias Influence Changes in Time Spent with Media. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 60(4), 604-623. 10.1080/08838151.2016.1234477 Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(2), 209-221. 10.1080/00223891.2015.1068174 Leary, M. R., Diebels, K. J., Davisson, E. K., Jongman-Sereno, K. P., Isherwood, J. C., Raimi, K. T., Deffler, S. A., & Hoyle, R. H. (2017). Cognitive and Interpersonal Features of Intellectual Humility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(6), 793–813. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0146167217697695 Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., Crigler, A. N., & Marcruen, M. (2007). The Affect Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Political Thinking and Behavior. University of Chicago Press. Mason, L. (2016, March 21). A Cross-Cutting Claim: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 351-377. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw001 Mason, L. (2018, March 21). Ideologues without issues. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(Special Issue 2018), 866-887. 10.1093/poq/nfy005 McElroy, S. E., Rice, K. G., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., Hill, P. C., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2014). Intellectual humility: Scale development and theoretical elaborations in the context of religious leadership. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 42(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164711404200103 Pew Research Center. (2014, June 12). The Ideological Consistency Scale. Political Polarization in the American Public. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/appendix-a-the-ideological-co nsistency-scale/ Pew Research Center. (2020, November 13). America is exceptional in the nature of its political divide. PewResearch.org. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/13/america-is-exceptional-in- the-nature-of-its-political-divide/ Porter, T., & Schumann, K. (2017). Intellectual humility and openness to the opposing view. Self and Identity, 17(2), 139-162. Rollwage, M., Dolan, R. J., & Fleming, S. M. (2018, December 17). Metacognitive Failure as a Feature of Those Holding Radical Beliefs. Current Biology, 4014-4021. Schaewitz, L., Kluck, J. P., Klosters, L., & Kramer, N. C. (2020). When is Disinformation (In)Credible? Experimental Findings on Message Characteristics and Individual Differences. Mass Communication and Society, 23(4), 484-509. 10.1080.15205436.2020.1716983 Stanford University & Dweck, C. S. (1999). Growth Mindset Scale. stanford.edu. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from http://sparqtools.org/mobility-measure/growth-mindset-scale/#all-survey-questions Tavris, C., & Aronson, E. (2007). Mistakes Were Made (But not by Me): Why we Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Weeks, B. E. (2015). Emotions, Partisanship, and Misperceptions: How Anger and Anxiety Moderate the Effect of Partisan Bias on Susceptibility to Political Misinformation. Journal of Communication, 699-719. 10.1111/jcom.12164 Weeks, B. E., Kim, D. H., Hahn, L. B., Diehl, T. H., & Kwak, N. (2019). Hostile Media Perceptions in the Age of Social Media: Following Politicians, Emotions, and Perceptions of Media Bias. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 63(3), 374- 392. 10.1080/08838151.2019.1653069 Westfall, J., Boven, L. V., Chambers, J. R., & Judd, C. M. (2015). Perceiving Political Polarization in the United States: Party Identity Strength and Attitude Extremity Exacerbate the Perceived Partisan Divide. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 145-158. 10.1177/1745691615569849 Young, D. G. (2020). The Psychology of the Left and the Right. In Irony and Outrage: The Polarized Landscape of Rage, Fear, and Laughter in the United States (pp. 100-118). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oso/9780190912083.003.0006 Zabinski, A. M., & Bolsen, T. (2017). Party Identity and Evaluation of Political Candidates. Georgia State Honors College Undergraduate Research Journal, 4(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.31922/disc4.1 AppendixSuggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Psychology |