The Career Value of the Humanities & Liberal ArtsThe Evolution—Not Extinction—of Degrees in the 'Arts & Humanities'

In 2013, the Wall Street Journal published an article based on the findings of a Harvard University study stating that “the percentage of humanities degrees (as a share of all undergraduate degrees attained) has dropped by half since the 1960s.” According to the Harvard study, liberal arts and humanities are “attracting fewer undergraduates amid concerns about the degrees’ value in a rapidly changing job market.” Harvard and the WSJ’s inference was that there are no jobs—and hence no money—for graduates of liberal arts and humanities programs. Following this study, liberal arts departments and humanities scholars all over the country dove into research with the intent of answering two questions:

The answer they found was slightly more nuanced: While graduates with humanities and liberal arts degrees may earn less immediately after graduating, in the long run they actually earn more on average than those with professional degrees.

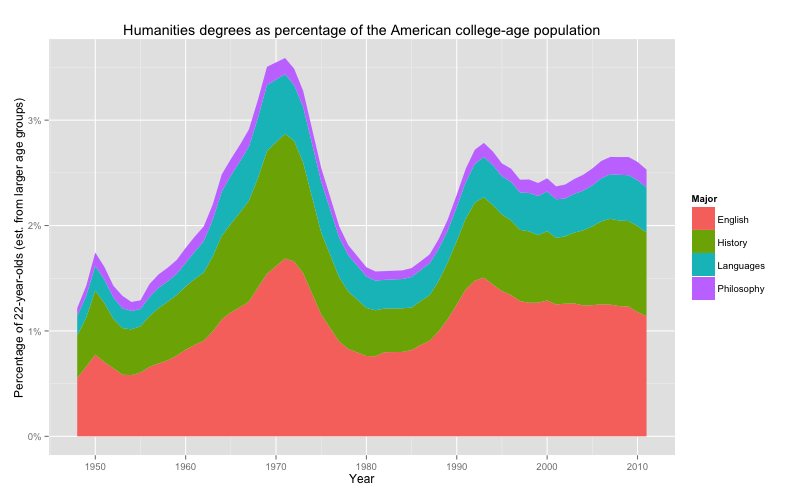

True Numbers, but Slanted ImplicationThe answer to the question about enrollment in humanities and liberal arts programs, researchers found, is that while there has been a drop off, it has been small. Enrollment has dropped since the peak it achieved during the Vietnam War. However, when compared to 1950s numbers, enrollment percentages are only slightly lower. More importantly, “the percentage of college-age Americans holding degrees in the humanities has increased fairly steadily over the last half-century, from a little over one percent in 1950 to about 2.5 percent today,” according to Harvard graduate and Northeastern University professor Ben Schmidt. Questioning the Realities of a Bachelor of Arts DegreeIn an era of rising higher education costs, the debate over the value of obtaining a liberal arts degree is important. Yet just as some seemed ready to write off the value of these programs, many others are finding that the conceptual and analytical skills that study in the humanities and liberal arts promotes are becoming more crucial than ever before. Ironically, this may be particularly true in the field of tech, which tends to be dominated by coders and engineers. As George Anders writes for Forbes, “The more that audacious coders dream of changing the world, the more they need to fill their companies with social alchemists who can connect with customers–and make progress seem pleasant.” Humanities, liberal arts and social science majors are often saddled with clichés linking a bachelor of arts degree with the ability to reason and write, but few other skills. Traditionally, the assumption was made that graduates with degrees in other fields of study had larger skill sets and could write and reason. But that is no longer the case. According to Verlyn Klinkenborg, a professor of nonfiction writing who has taught at Harvard, Yale, Bard, Pomona, Sarah Lawrence and Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism, “many college students graduate without being able to write clearly.” In technical fields, this skill is simply not as important and thus not practiced and perfected. While doing research in both science and humanities journals for their book Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa discovered that “Students majoring in liberal arts fields see ‘significantly higher gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills over time than students in other fields of study.'” By contrast, students majoring in business, education, social work and communications showed the smallest gains. Yet critical thinking and complex reasoning are crucially important to success in the marketplace. Short and Long-Term Employment Realities of Liberal Arts and Humanities GraduatesGaining employment as a liberal arts or humanities major can be difficult and often means taking a salary that is less than one’s counterparts. Studies indicate, however, that in the end, liberal arts or humanities majors actually make more money than the vast majority of graduates with degrees in other fields. In Inside Higher Ed, Allie Grasgreen reports, “By their mid-50s, liberal arts majors with an advanced or undergraduate degree are on average making more money than those who studied in professional and pre-professional fields, and are employed at similar rates” According to a joint report conducted by AAC&U and the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, “while in the years following graduation they earn $5,000 less than people with professional or pre-professional degrees, liberal arts majors earn $2,000 more at peak earning ages.” This long-run advantage takes hold, in particular, when liberal arts and humanities graduates go on to obtain graduate degrees. Humanities is the FutureAs technology continues to expand and the number of people with high levels of technical proficiency grows, a greater number of the available jobs will require the multidisciplinary skill set provided by a bachelor of arts degree. Technical jobs are often easier to mechanize, particularly as our computing abilities continue to grow and as our societies become increasingly networked. “The humanities are a good bet because the things that are hardest to computerize or outsource are going to be all about skills that emphasize human interaction. Empathy, sociability, writing, analyzing, and reacting to people — all things more likely to come from the humanities than hard sciences.” The liberal arts and humanities teach students to think at an abstract level and to make connections that technology, so far, simply cannot emulate. In this sense, these degrees teach more than just skills, but rather a way of thinking that will always have an important, strategic value—even in a marketplace that is based on scientific and technological development. |

Comments & Discussion