Surviving Grad School Archives - Inquiries Journal - Blog ArchivesDecember 7th, 2016 The Career Value of the Humanities & Liberal ArtsIn 2013, the Wall Street Journal published an article based on the findings of a Harvard University study stating that “the percentage of humanities degrees (as a share of all undergraduate degrees attained) has dropped by half since the 1960s.” According to the Harvard study, liberal arts and humanities are “attracting fewer undergraduates amid concerns about the degrees’ value in a rapidly changing job market.” Harvard and the WSJ’s inference was that there are no jobs—and hence no money—for graduates of liberal arts and humanities programs. Following this study, liberal arts departments and humanities scholars all over the country dove into research with the intent of answering two questions:

The answer they found was slightly more nuanced: While graduates with humanities and liberal arts degrees may earn less immediately after graduating, in the long run they actually earn more on average than those with professional degrees.

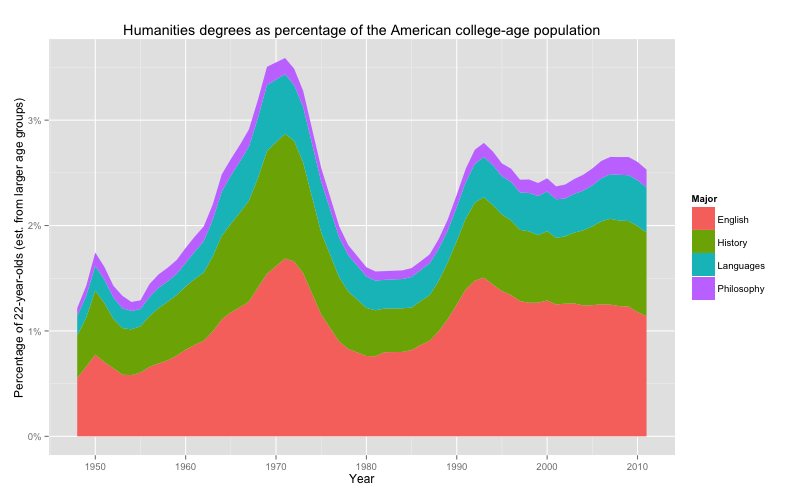

True Numbers, but Slanted ImplicationThe answer to the question about enrollment in humanities and liberal arts programs, researchers found, is that while there has been a drop off, it has been small. Enrollment has dropped since the peak it achieved during the Vietnam War. However, when compared to 1950s numbers, enrollment percentages are only slightly lower. More importantly, “the percentage of college-age Americans holding degrees in the humanities has increased fairly steadily over the last half-century, from a little over one percent in 1950 to about 2.5 percent today,” according to Harvard graduate and Northeastern University professor Ben Schmidt. Questioning the Realities of a Bachelor of Arts DegreeIn an era of rising higher education costs, the debate over the value of obtaining a liberal arts degree is important. Yet just as some seemed ready to write off the value of these programs, many others are finding that the conceptual and analytical skills that study in the humanities and liberal arts promotes are becoming more crucial than ever before. Ironically, this may be particularly true in the field of tech, which tends to be dominated by coders and engineers. As George Anders writes for Forbes, “The more that audacious coders dream of changing the world, the more they need to fill their companies with social alchemists who can connect with customers–and make progress seem pleasant.” Humanities, liberal arts and social science majors are often saddled with clichés linking a bachelor of arts degree with the ability to reason and write, but few other skills. Traditionally, the assumption was made that graduates with degrees in other fields of study had larger skill sets and could write and reason. But that is no longer the case. According to Verlyn Klinkenborg, a professor of nonfiction writing who has taught at Harvard, Yale, Bard, Pomona, Sarah Lawrence and Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism, “many college students graduate without being able to write clearly.” In technical fields, this skill is simply not as important and thus not practiced and perfected. While doing research in both science and humanities journals for their book Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa discovered that “Students majoring in liberal arts fields see ‘significantly higher gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills over time than students in other fields of study.'” By contrast, students majoring in business, education, social work and communications showed the smallest gains. Yet critical thinking and complex reasoning are crucially important to success in the marketplace. Short and Long-Term Employment Realities of Liberal Arts and Humanities GraduatesGaining employment as a liberal arts or humanities major can be difficult and often means taking a salary that is less than one’s counterparts. Studies indicate, however, that in the end, liberal arts or humanities majors actually make more money than the vast majority of graduates with degrees in other fields. In Inside Higher Ed, Allie Grasgreen reports, “By their mid-50s, liberal arts majors with an advanced or undergraduate degree are on average making more money than those who studied in professional and pre-professional fields, and are employed at similar rates” According to a joint report conducted by AAC&U and the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, “while in the years following graduation they earn $5,000 less than people with professional or pre-professional degrees, liberal arts majors earn $2,000 more at peak earning ages.” This long-run advantage takes hold, in particular, when liberal arts and humanities graduates go on to obtain graduate degrees. Humanities is the FutureAs technology continues to expand and the number of people with high levels of technical proficiency grows, a greater number of the available jobs will require the multidisciplinary skill set provided by a bachelor of arts degree. Technical jobs are often easier to mechanize, particularly as our computing abilities continue to grow and as our societies become increasingly networked. “The humanities are a good bet because the things that are hardest to computerize or outsource are going to be all about skills that emphasize human interaction. Empathy, sociability, writing, analyzing, and reacting to people — all things more likely to come from the humanities than hard sciences.” The liberal arts and humanities teach students to think at an abstract level and to make connections that technology, so far, simply cannot emulate. In this sense, these degrees teach more than just skills, but rather a way of thinking that will always have an important, strategic value—even in a marketplace that is based on scientific and technological development. Tags: College Majors, graduate school, Higher Education, Humanities, Liberal Arts November 23rd, 2016 What is the Secret to Success?At hundreds of colleges and universities across the country, thousands of students are in the midst of the fall semester, trying to manage the academic tasks of studying, exams, papers and lectures. A lot is riding on their academic performance – earning (or just keeping) scholarships, landing summer internships, gaining employment and of course acquiring new skills and knowledge. The vast majority of students will tell you they intend to do well, that they know it takes hard work to succeed. But some students will end up hitting more bars and parties than books. That is, not everyone ends up putting in that hard work. In our own work, we have found that asking college students questions like, “How important do you think it is to do well at college?” gives us essentially no information about who will do well in terms of grades. College students are hardly unique in not following through on their intentions and goals. Frustrated parents might do well to look to their own unused gym memberships or perennial weight-loss resolutions to realize that intentions are not always sufficient to ensure steady progress toward one’s goals. Why is there such a disconnect between our intentions and our actions? And, how can we predict who has the grit to succeed, if we can’t depend on what people tell us?

Explicit or Implicit Beliefs?When people are directly asked how important they think it is to succeed at some goal, they are reporting their “explicit beliefs.” Such beliefs may largely reflect people’s aspirations, such as their sincere intentions to buckle down and study hard this semester, but these may not always map onto their subsequent inclination to persist. Rather than depend on people’s explicit beliefs, in our research we looked instead to people’s implicit beliefs. Implicit beliefs are mental associations that are measured indirectly. Rather than asking the person to state what they think about some topic, implicit measures use computerized reaction-time tasks to infer the strength of someone’s implicit associations. For instance, a great deal of research by psychologists Brian Nosek, Tony Greenwald and Mahzarin Banaji over the last two decades has shown that people often hold negative implicit associations about members of stigmatized racial and ethnic groups. Even though many participants in these studies explicitly stated they believed in fairness and equality among racial groups, they nevertheless showed implicit biases toward racial and ethnic groups. In other words, whereas people “said” they were egalitarian, they in fact possessed strong negative associations in their mind when it came to certain racial groups. Implicit associations are critical to understand because they can predict a range of everyday behaviors, from the mundane (what foods people eat) to the monumental (how people vote). But do implicit associations predict who has the grit to succeed at life’s difficult goals? Here’s What We didTo find out, instead of measuring people’s explicit beliefs about the importance of their goals, we measured people’s implicit beliefs about the importance of an area (e.g., schoolwork, exercise) and then measured their success and persistence at relevant tasks (e.g., grades, gym regimens). We used a computer-based test called the “Implicit Association Test (IAT)” to measure our participants’ implicit beliefs. The test takes about seven minutes to complete. Participants have to don noise-canceling headphones and sit in a distraction-free cubicle. In five of our studies, we used this test to measure students’ cognitive association between “importance” and “schoolwork.” Student participants were asked to indicate, as quickly as they could, using computer keys, whether each of a series of words was related to “schoolwork,” was a synonym of “importance” or was a synonym of “unimportance.” Examples of such words included “exam,” “critical” and “trivial.” The test was set up in such a way so that even a slight difference in the speed of response (at the level of milliseconds) could reveal differences in the strength of the association between schoolwork and importance. In short, it allowed us to measure the extent to which people implicitly believed that schoolwork was important. Multiple Studies to CorroborateCould millisecond differences in reaction times meaningfully capture people’s beliefs and predict success in their goals? For instance, could this seven-minute-long measure of milliseconds predict who would earn straight A’s in their college classes? We found that they did. And we didn’t observe this relationship just once. We found that again and again – across seven different studies, run in different labs, with different populations and predicting different types of persistence and success. Across five studies, we found that college students’ implicit belief in the importance of schoolwork predicted who got higher grades. We didn’t limit our study to college performance. We also tested other goals, such as going to the gym. We found that those who had a stronger association between importance and exercise were significantly more likely to exercise more often and more intensely. Then we conducted a test to find out how implicit beliefs predicted test-taking abilities. We tested college students’ implicit beliefs about the importance of the GRE (Graduate Record Examination), a widely used exam that helps determine graduate school admissions and scholarships. Those who showed a stronger association between importance and the GRE scored significantly better on a practice GRE test. A Unique Measure of Likelihood of SuccessLike any measure, ours wasn’t perfect. We couldn’t always predict in every instance who would succeed or fail. But our brief computerized test provided new insight into who was likely to succeed – an insight not captured by more traditional measures. For example, higher SAT scores are taken to be a measure of who will likely do better at college and better on the GRE. Our data did show that SAT scores are a good predictor of both. However, knowing participants’ implicit beliefs in the importance of school or the GRE predicted success over and above what SAT scores could tell us. In other words, even when two people scored the same on the SAT, the one with the stronger implicit belief about the importance of the GRE tended to score better on the practice exam. One interesting finding in our studies was that implicit beliefs predicted some people’s success more than others. Closer examination showed that those for whom exerting self-control was difficult – those who said they have trouble completing assignments on time, who could be easily dissuaded from making it to spin class or who have difficulty maintaining focus during long reading comprehension passages – were those who most benefited from having a strong implicit belief that the goal was important. In other words, it was those individuals in need of a boost who most clearly benefited from the implicit nudge that their pursuits were important. What Exactly is the Role of Implicit Beliefs?Our work adds to a growing body of evidence that the ordinarily hidden-from-view, implicit associations in our mind offer new insights about many everyday decisions and behaviors. Implicit associations can predict success at some of life’s most challenging tasks. For example, just as implicit associations can predict intergroup behavior, first impressions of other people and voting behavior, our new findings show that they also predict success at some of life’s most challenging tasks. However, there are still some questions that remain. For example, do implicit beliefs in the importance of working hard actually cause people to do better, or do they simply identify who is likely to succeed? Could changing people’s implicit beliefs have real effects on their prospects for success? To be clear: It is certainly not the case that what people say about how much they care about something does not matter at all. Indeed, we would guess that people who say they care nothing about exercising will not be heading to the gym, regardless of their implicit associations between exercise and importance. But, especially among those who say they do care about something – such as the vast majority of college students caring about their performance at school – a measure of their implicit beliefs may give us a better idea about how likely they are to succeed. Melissa J. Ferguson, Professor of Psychology, Cornell University and Clayton R. Critcher, Associate Professor of Marketing, Cognitive Science, & Psychology, University of California, Berkeley

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

November 6th, 2015 How to Use Regression Analysis EffectivelySo, you want to use regression analysis in your paper? While statistical modeling can add great authority to your paper and to the conclusions you draw, it is also easy to use incorrectly. The worst case scenario can occur when you think you’ve done everything right and therefore reach a strong conclusion based on an improperly conceived model. This guide presents a series of suggestions and considerations that you should take into account before you decide to use regression analysis in your paper. The best regression model is based on a strong theoretical foundation that demonstrates not just that A and B are related, but why A and B are related.

Before you start, ask yourself two important questions: is your research question a good fit for regression analysis? And, do you have access to good data? 1. Is Your Research Question a Good Fit for Regression Analysis?This depends on many different factors. Are you trying to explain something that is primarily described by numerical values? This is a key question to ask yourself before you decide to use regression. Although there are various ways to use regression analysis to describe non-numerical outcomes (e.g., dichotomous yes/no or probabilistic outcomes), they become more complicated and you will need to have a much deeper understanding of the underlying principles of regression in order to use them effectively. Before you start, consider whether or not your dependent variable is numerical. Some examples:

At the same time, you need to make sure that there is sufficient variation in your dependent variable and that the variation occurs in a normal pattern. For example, you would have a problem if you tried to predict the likelihood of someone being elected as president because almost no one is elected as president. As a result, there is virtually no variation on the dependent variable. 2. Do You Have Access to Good Data?Before you can conduct any type of analysis, you need a good data set. Not all data sets are easily suited to regression analysis without considerable manipulation. Some things to consider before you decide to use regression:

Keep in mind that your independent variables need to meet the same criteria for normality and variability as your dependent variable. Once you decide to proceed with a regression model in your analysis, there are a three key concepts to keep in mind as you design your model to avoid making an easily preventable mistake that could send your conclusions way off track.

Each is described in more detail below. ParsimonyIn statistics, the principle of parsimony is based on the idea that when possible, the simplest model with the fewest independent variables should be used when a model with more variables offers only slightly more explanatory value. In other words, one should not add variables to a model that do not increase the ability of the model to explain something. Only add variables to a model if they significantly increase the ability of the model to explain something. If you add too many variables to your model, you can unwittingly introduce major problems to your analysis. In the extreme case, you must consider that your R2 value will always increase with the addition of new variables: so if you examine R2 alone, you can be duped into thinking that you have a great model simply by dumping in more and more predictor variables. There are two good ways to address this problem: use an Adjusted R2 to compare models with different numbers of predictors, and use stepwise regression to analyze the explanatory impact of each variable as it is added to the model.

A good rule of thumb as you consider different models is that you should always have a good reason to add a predictor variable to your model, and if you can’t come up with a good theoretical explanation as to why A influences B, then leave out A! Internal ValidityInternal validity is the degree to which one factor can be said to cause another factor based on three basic criteria:

In many cases, internal validity becomes an issue in the form of a “chicken and egg” problem. For example, let’s say you are considering the relationship between obesity and depression (a common example). If you want to include depression as an independent variable to explain obesity in your model, you first need to consider the question: Does depression lead to obesity, or does obesity lead to depression? If you have no clear theoretical guidance to show that, in fact, depression usually precedes obesity (temporal precedence), you could introduce a significant problem to your model if the relationship is in fact the other way around: depression being the result of obesity. Therefore, as you craft your model it is important to have a theoretical basis for the inclusion of each variable. MulticollinearityMulticollinearity occurs when the independent variables in a multiple regression model are highly correlated with one another. This can be a problem in several ways:

An example of variables that are going to be highly multicollinear are any variables that effectively measure the same thing. One way to show this, for the purposes of an example, is to imagine converting categorical data into a series of binary variables. Any variables that effectively measure the same concept are likely to have high collinearity. For example, let’s say that we have a variable measuring memory where respondents are able to choose very good, average, or poor as a response. One way to use this data in a regression model would be to convert the data into three dichotomous (yes/no) variables indicating a person’s response. However, if you then include all of these dichotomous variables in your model, you will have a big problem because they will become perfectly multicollinear. This is because anyone who indicated that they had a very good memory, by default, also indicated that they do not have a poor memory. The two variables measure the same thing: a person’s memory. Another common example can be found in the use of height and weight variables. Although the two variables measure different things, broadly speaking they can both be said to measure a person’s body size, and they will almost always be highly correlated. As a result, if both variables are included as predictors in a model, it can be difficult to discern the effect that each variable has individually on the outcome (measured by the coefficient). Thus, as you build your model, you need to be aware of the potentially confounding impact of using highly similar predictor variables. In an ideal model, all independent variables will have no or very low correlation to each other, but a high correlation with the dependent variable. Conclusion: Use Regression Effectively by Keeping it SimpleRegression analysis can be a powerful explanatory tool and a highly persuasive way of demonstrating relationships between complex phenomena, but it is also easy to misuse if you are not an expert statistician. If you decide to use regression analysis, you shouldn’t ask it to do too much: don’t force your data to explain something that you otherwise can’t explain! Moreover, regression should only be used where it is appropriate and when their is sufficient quantity and quality of data to give the analysis meaning beyond your sample. If you can’t generalize beyond your sample, you really haven’t explained anything at all. Lastly, always keep in mind that the best regression model is based on a strong theoretical foundation that demonstrates not just that A and B are related, but why A and B are related. If you keep all of these things in mind, you will be on your way to crafting a powerful and persuasive argument. Tags: academia, Modeling, Regression, research, Research Guide, Stats March 30th, 2015 How to Manage a Group Project (Video)Group work is an inevitable part of most university courses and the ability to work well with other people is something all employers care about. While working on a group project can be incredibly rewarding, it can also present real challenges if you don’t go in with the right mindset. Here are a few tips to make group work just a little bit easier! Be Prepared to Compromise

Something we must learn early in life is that different people have different working styles. While some people like to have an essay planned out and written weeks in advance, others thrive on the pressure of leaving it until the last minute. Be open about how you work from the start – if you talk about the ways in which each person works best right away, you can come up with a compromise that suits everyone. If everyone compromises a little – for example, by agreeing to pre-planned deadlines – this can help avoid leaving some group members stressed or upset by discovering that their expectations were out of line with the rest of the group.

Maximize Each Member’s StrengthsDo you love public speaking? If so, great – tell your group members that from the start! Break down everything that has to be done, from conducting the research to preparing the slideshow and giving the presentation in front of the class, and assign tasks to each person based on their strengths. While it can be difficult to please everyone, having an honest discussion about strengths/weaknesses early on and and attempting to give everyone tasks that they’re comfortable with will benefit the entire group in the end. Stand Up for Yourself and Do the WorkPeople have different personalities, so if you are naturally shy and are put in a group with someone more confident, it can be tempting to shrink up and not say or do anything, even when you think that the group might be headed in the wrong direction – this is a mistake! As scary as it is, make sure you stand up for yourself and speak up. This is the only effective antidote to groupthink and conversations where not everyone immediately agrees can be incredibly fruitful. Of course it goes without saying, always put in the work. Don’t be the person that shows up with the job half done. It is common for group projects to include peer assessments and if you don’t put in the effort, your classmates won’t be shy. Choose Your Group WiselyIf you are given the opportunity to choose your group members, the temptation is often to work with your friends. Sometimes that is for the best because you know each other well and it can make working on the project more fun and less stressful. However, it can also lead to even more tension, particularly if you aren’t diligent about assigning tasks and preparing some deadlines from the get go. Someone who you have a lot of fun with on a night out might not make the best partner for a group project. (For one thing, this can make it much easier to get distracted!) There are also a lot of benefits to working with people you don’t know – it can give your project a wider range of perspectives and help you capitalize on differentiated skills as a group. Moreover, you might even end up making a great new friend. Tags: college, group projects, group work, study tips March 23rd, 2015 Presentation Tips 101 (Video)Presentations have become an integral part of most university and college courses. While some students won’t think twice before getting up to speak in front of a room full of people, for others, the thought of being in the spotlight can become overwhelming. It’s natural to be nervous, but for many students, those nerves can spiral out of control, making you feel anxious for days leading up to the event. Here are a few tips which will hopefully help to make you feel as comfortable as possible before giving your next group or solo presentation!

Perfect Your SlidesIf you are required to make a visual background for your presentation on something like PowerPoint, make a really good job of it! Rather than cobbling together some blank slides with a couple of paragraphs on them the night before, take some time to make them look amazing! A well-structured, nicely designed slideshow will show your teacher and classmates that you put a lot of work into the presentation. This tells your audience that any visible nerves are purely due to public speaking and not from a lack of preparation. Having your key points outlined briefly on your slides also means that if your nerves get the better of you and you lose track of where you are, your slides will quickly guide you back to where you were. Practice, Practice, Practice!It sounds obvious, but the worst thing you can do if public speaking worries you is not run through your presentation a good few times in advance! Start off alone, speaking aloud in your bedroom or an empty classroom. Then ask some friends to act as a test audience for you. Not only will this likely lead to useful feedback on your content, but it will make you feel more comfortable in front of a crowd, too! It allows you to practice key strategies — such as eye contact — which will improve your presentation. Your tutor wants to see that you are engaging with the class, so getting used to being in front of others is really helpful. Make Use of Note CardsNote cards can be a useful tool to take advantage of, but do make sure you check that you are allowed to use them first! Having cards with brief summaries (not the full script of your presentation) can help to keep you on track and, much like the slideshow, can give you the confidence of knowing exactly what’s coming next. However, they can also be a useful tool to stop you from fidgeting, something which is ever so tempting when you’re nervous! If you have cards to hold, you won’t be as likely to touch your hair, fidget with a pen or fiddle with your jacket! Plan Something Nice for Later!Depending on your schedule, if you can afford to take a little time out to go out for dinner with friends, go to the cinema, or even just go for a walk round the shops – do it! Knowing you have something fun planned for after the big event can make it so much easier to get through the stress of a presentation. You might still be nervous, but knowing that no matter what, the rest of your day is only going to get better, is a great feeling! That alone might be enough to make you feel more settled. Tags: college, presentations, student life, study tips, videos March 10th, 2015 Finding Balance in Graduate SchoolIn the darkest days of the graduate school “doldrums,” as you wade through readings and midterms and papers, it can be hard to recall why exactly you decided to go to grad school in the first place. Even though you might feel like you can hardly find time to breathe, the truth is you can make time for relaxing, catching a movie, spending time with your partner, or whatever else you enjoy — if you try. How can you balance graduate school with enjoying your personal life? Here are five things you can try:

Grad school can often feel like a 24/7 job where you need to be thinking about your research, coursework, and teaching all the time in order to compete in the academic job market. Not so! If you discipline yourself, you can work a semi-regular “shift” and still make time for dating, relaxing, and hobbies. Figure out when your most productive daytime hours are, and schedule 8-10 working hours during that time. If you stay on task during these hours, you can feel good about shutting it down to enjoy some personal time. Of course there will always be emergencies and last-minute deadlines, but by scheduling working shifts you can actually minimize their occurrence and lead a more ‘normal’ day-to-day life.

Procrastination during your scheduled hours will drag work into your personal time, so you need to find strategies to stay productive and on task. Download an app that blocks time-wasting websites; write from a computer with internet disabled; meditate or go for a walk – whatever you have to do to stay on task. Schedule short breaks every 60 to 90-minutes so that you stay energized and give your brain some relief.

If you’ve ever had a pet, you know how effective small rewards can be. But you are trainable, too! Set realistic goals for yourself and then reward yourself when you meet them. Small rewards for finishing tasks or meeting goals can go a long way toward keeping you motivated. Figure out what you respond to – a Starbucks coffee? A homemade cookie? A night out dancing? – and reward yourself when you meet set goals. The more that you give yourself rewards, the more you will be willing to meet your own goals when you set them.

Some people dislike the idea of penciling in their partners or setting aside a block of time for pleasure reading – but given how graduate school work tends to expand to fill all of your time, scheduling off chunks of time to take care of your personal needs might be the smartest way to make sure they don’t get constantly sidelined. So schedule yourself some free time, put your school work away, and indulge. You’ll find that the more you allow yourself to refresh your brain, the more you will actually get done when it’s time to work – because your mind will be focused on work, and not how tired of working you are.

It’s easy to envision yourself working productively around the clock to finish academic obligations or publish one more paper. The flip side is that you often guilt yourself when you aren’t working – you think that any minute you spend relaxing could be spent working! But the truth is, even if you love your research area, it’s easy to get “burned out” in academia. If you work around the clock, you can get disillusioned and discouraged. The more exhausted you are mentally and spiritually with your work, the harder it is over the long-term for you to produce high-quality scholarship. You have to take breaks in order to produce your best work. Divest yourself from the guilt that graduate school can bring. Whenever you feel guilty for spending time on non-work things, mentally change the subject and remind yourself that it’s OK to spend time relaxing and recharging – even more, it’s healthy. So divest yourself from the guilt that graduate school can bring. Whenever you feel guilty for spending time on non-work things, mentally change the subject and remind yourself that it’s OK to spend time relaxing and recharging – even more, it’s healthy. This is a “fake it ’til you make it” kind of thing – you will have to actively pretend you don’t feel guilty at first. Spend more time focused on producing the highest quality work and less time on berating yourself. Beating yourself up is never productive anyway! So stay positive and learn to focus on a positive reinforcement-based schedule. The more you do this, the less guilt you will eventually learn to feel during time off. Tags: academia, graduate school, personal life, research, work December 4th, 2014 How to Select a Graduate Research AdvisorIf you attend a doctoral program, you’ll absolutely need a research advisor – someone to guide you along the way in your research activities and help train you to become an independent scholar. Even if you are headed to a master’s program, a research advisor can be a valuable asset, particularly if your eventual goal is to get into a doctoral program. Many doctoral and master’s students are assigned an advisor, but many more are presented with a myriad of choices and are baffled at how to go about selecting one. Here’s some advice for selecting a research advisor in graduate school. (This advice is primarily applicable to doctoral students, but master’s and professional students should find these suggestions useful, too.)

What is a Research Advisor?An advisor is a professor who is largely responsible for your progress through the program. In the early stages, they will help you select classes and get started on you first research tasks. Towards the end, they will most likely become the chair or sponsor of your dissertation committee, and guide you in the process of conducting the dissertation. They will also shepherd you through the research process and encourage you to present at conferences and publish papers in journals in your field. Less tangibly, through word and deed they will educate you on the conventions of your field, and if things work out, their networks will become your networks. Through word and deed your advisor will educate you on the conventions of your field, and if things work out, their networks will become your networks. They may assist you in getting a postdoc and/or a final position (within academia or without), and they will be the person writing your letters of recommendation for jobs and funding. Needless to say, advisors have a huge impact on the trajectory of your career, so it’s important to select wisely! I like to group advisor characteristics into three main buckets:

Each is very important, but each individual student needs to decide which bucket(s) are most important to them. Research Interests and ProjectsOne of the primary concerns of an advisor is to select someone whose research interests are similar to yours. Particularly in the sciences and social sciences, an early doctoral student may work on their advisor’s research project(s) until they get their own projects up and running. Their final dissertation project and many of their papers will likely be based largely upon projects their advisor has available. The key here is to find someone who has interests that are similar to yours – but they don’t have to match exactly. In fact, they should not match exactly; if someone senior to you is already doing exactly what you want to do, you haven’t found an untapped research niche and you need to redirect a little. It’s also very likely that your interests will morph throughout graduate school, so you need to find someone with a broad knowledge base who can help guide you as you grow as a researcher. Another potentially important issue is funding; in many programs, the advisor is primarily responsible for your stipend and tuition coverage, so you’d need to find an advisor who has an active grant with a line item for an RA or other suitable position. If you are not yet in grad school, you can find this person by reading intriguing scientific journal articles in your field and noting authors who appear often in your reading list; by perusing the websites of graduate programs in which you are interested, and reading the project and research descriptions there (although they are sometimes a bit out of date); and by perhaps attending some national or regional conferences and meeting with presenters who have interesting presentations. To find about funding status, you can use tools like NIH RePORTER or the NSF Award Search to see if a professor you are interested in has an active grant. If you are already in graduate school – go talk to the professors in your department! Attend brown bags and colloquia to hear what your professors are doing, and take their classes. Some science programs have lab rotations that allow you to work with 2-3 people on a trial basis. If not, don’t be afraid to set up short meetings with professors in your department to learn more about their work. However, do your due diligence: read their most recent articles and talk to their current grad students to get an idea of on what they are currently working on. Professional Qualities and CharacteristicsAfter considering research interests, think about the professional qualities of a potential advisor. An advisor’s position in the field and approach they take towards the field can have a large impact on the way you work with them and your own prospects on the job market. Take into account their research productivity: how much have they published in the last few years? Do they have grant funding? Are their research labs well-appointed? You can also try to evaluate the extensiveness of their networks. Do they know other people in the field – people that you might want a job or postdoc with someday? Are they generally well-regarded in your area? Do they regularly attend conferences and other professional development activities? This may be difficult to judge ahead of time, but asking one of their current grad students can help. It also helps to assess your potential advisor’s standing in the department. When you attend departmental events, casually observe their interactions with their colleagues and with other grad students. Do they show up to things? Are they generally well-regarded in the department? Do they have issues or conflicts with many other professors or people who might later serve on your committee? An advisor who gets along with their peers is an advisor that can grease the wheels for you if you have issues during the course of your program. Personality CharacteristicsMany graduate students do not consider personality characteristics when selecting an advisor – they assume that if the research interest is there, they will be able to work with the person. This is not so. In fact, in some cases it may be a better idea to work with someone with a weaker fit but who has a personality more compatible with yours. This is information that is best gleaned from current graduate students! However, much of this can also be subtly picked up during a brief meeting with a professor to assess research fit. For this step, you need to evaluate your own needs and desires. What is your approach to your work – more 9-to-5, or any time? Do you want to be a superstar who works 80 hour weeks? Many professors are themselves workaholics, and they will expect you to push yourself to their limit – sometimes forgoing social and personal concerns to do so. Other professors have a better work-life balance and will encourage the same from you. You need to find an advisor whose outlook fits yours. Are you independent and self-motivated or would you like a little more guidance (at least in the beginning)? Some advisors have a more hands-on style of mentoring, giving their students research projects on which to work, meeting with them more often and directing their analyses. Others take a much more hands-off approach, allowing students to explore and find their own way while being generally available for guidance and advice. Finding someone who matches your own preference will make life easier. Your research advisor has significant influence on your career – as well as a big impact on your experience during your graduate career. It’s important to consider the choice carefully and find an advisor who fits you both professionally and personally. If chosen correctly, however, your advisor can become a trusted mentor – and friend – for many years to come. November 9th, 2014 Writing a Graduate School Personal StatementMost graduate programs require students to write a “personal statement” or “statement of purpose” as part of the application process. This is true for master’s, doctorate, and professional graduate programs. And for many, this is the most difficult part of the application. The upside of your personal statement is that it’s a part of your application over which you have total control: your grades and test scores are set; others will be writing your letters of recommendation; and your CV/resume will be a product of experiences you have accumulated over many years. The personal statement is your biggest opportunity to improve your application. So how can you write a good one?

Generally speaking, your statement of purpose will contain three main sections:

While opinions differ on how much space you should devote to each section, my personal advice is to allow about 40% for past experiences, 40% on current interests, and the remaining 20% on career goals and ambitions.

This section should concentrate on answering two key questions:

This should not just be a rehash of your CV. Instead, you want to thoughtfully select a few standout experiences and discuss how they have provided you with a passionate interest in the field and the basic knowledge necessary to excel in a graduate program. For those seeking a research-based degree, discussing research experience is a no-brainer while those going into professional programs might discuss previous jobs or internships and how they related to your interests. What exactly do they mean by “personal” statement?Although it’s called a “personal statement,” one thing you should keep in mind is that the personal statement isn’t really “personal.” Graduate schools are interested in your personal professional life. Therefore, you want to keep the tone and the examples given in your statement professional. The admissions board isn’t interested in the fact that you’ve wanted to be a paleontologist since you were five years old, or that you’ve “always” wanted to be a college professor. Not only are these themes overused and cliché, they can give off the impression that you are not treating your future career seriously – that you are still looking at the field through the lens of a dreamy child instead of a thinking adult. If it helps, think of the “personal statement” as a “professional statement” and don’t get bogged down in stories that don’t fit that theme.

Likewise, you should avoid personal struggles that inspired you unless they are unusually profound. In clinical psychology, a very common theme is to write about a family member’s mental illness that made them want to enter the field (or even one’s own). But a large recent study of graduate admissions officers have labeled this a “kiss of death” for graduate admissions. The same goes for writing about how a family member’s serious illness made you want to become a physician, or that a favorite cousin was an engineer. What time period should you focus on?Focus on accomplishments from college and beyond. Frankly, the accomplishments you made in high school no longer matter, so you don’t want to discuss being a National Merit Scholar or being on high school Model UN. The rare exception would be if you did something truly exceptional in the later stages of high school (i.e., if you are applying to a music performance program and played at Carnegie Hall, or if you are applying to a science research program and did research with a professor or won the Intel STS in high school). Otherwise, stick to things that you accomplished after you graduated from high school.

Your second section should be about your current research and/or professional interests and why the program you’re applying to is a good fit for you and for them. If you are applying to research programs, you should describe in detail the kind of research you want to be involved in. If you are applying to professional programs, you’ll need to talk about your current professional interests as they relate to the field. How specific do you need to be? If you are too vague, it appears as though you haven’t quite thought through your professional interests. But if you are too specific, you may end up proposing something that is not feasible at the institution you’re applying to. It’s best to propose a relatively broad area of inquiry, allowing room for exploration, with some sharper details sprinkled throughout in a way that portrays you as someone with a clear focus who can also be flexible. You also need to make sure that you tailor your personal statement to reflect the program at each individual institution that you apply to. This is probably the best section to do that. You should make it clear that you have done background research into the university, department, and program that you’re applying to. If you’re applying to a PhD or Master’s program with an interest in research, you should try to mention two or three faculty members in the department who are doing research that interests you (and who could potentially serve as your faculty advisor). If the university has any special libraries, collections, centers, initiatives, or sub-programs that are particularly unique, describe how access to those resources will specifically help you reach your research and career goals. You want to convey to the admissions committee that you have done your homework, and that their university is the best place for you.

This last section of your statement should focus on your future career goals and how their program can help you achieve them. Graduate committees are interested in what their applicants plan to do with their degree, since those people will go on to represent the university in the world. You should present some clear goals in this section, even if you’re not absolutely certain about what your goals are. Remember, at this stage your primary goal is to get into the best graduate program that you’re able to. Once you’re in, your career goals can change — and they probably will. The faculty at the university you’re applying to have all gone through the same process themselves and they know and expect that everyone’s goals and aspirations change. If you don’t know whether or not you want to enter academia, that’s OK: after all, this will likely be your first foray into professional academia, so how could you know? Instead, emphasize your broad ambitions and the ways in which their program can enable you to succeed over a spectrum of different goals. This is a good note to end on, as you repeat here that their university is an ideal fit based on your experiences, your interests, and your future goals. Tags: graduate school admissions, graduate school applications, personal statement October 25th, 2014 How to Read for Grad SchoolOne of the very first things you’ll learn in graduate school is that your professors will assign a lot of reading. A lot of reading! Depending on your field, each week you may be asked to read anywhere from several journal articles (mainly STEM fields) up to an entire book per class (social sciences and humanities). How can you manage all of this reading? Here are a few tips to help get you through those pages.

The first thing is to recognize that you can’t read all of it in the time allotted. Graduate professors, quite deliberately, usually assign more reading than the average graduate student can complete in a given week. With research, teaching, sleeping, eating, and your personal life, there aren’t enough hours in the day to read all of the materials you are assigned. This means that you’re going to have to get creative in how you manage the reading load so that you cover the material requested.

Since you know that you can’t read it all, you’re going to have to figure out which of the readings are most important for a particular week. Start by organizing your readings into three groups:

But how do you determine which assignments to read closely and which to put on the back burner? Sometimes professors will make it obvious by designating certain readings as “required” and others as “optional,” or by foreshadowing what you’ll talk about in your next session. You can try to surmise this yourself by quickly looking through the materials that are assigned and finding their common theme. From there, you should be able to determine which readings are ‘core’ and which are peripheral to the main theme. What about ease of reading? It’s tempting to select the papers or books that you think will be the easiest to get through, but take caution. Often, the thorniest theoretical papers are the seminal ones that are the heart of the themes your graduate professor is trying to convey. They’re likely to be on your qualifying exams down the road. But if two or more papers look equally important and have similar purposes in the assigned readings, sometimes a good strategy is to pick the one that captures your interest most. Read ‘Closely’ by Taking NotesDoing a “close reading” of graduate school papers is not like reading a pleasure book. You’re looking for key themes and discussion points – things that are relevant to your research and scholarship. When doing your close readings, take notes! If you are using a paper copy, you can annotate right onto the paper. If you’re averse to writing on your paper – or don’t have enough room – brightly colored sticky notes can help flag specific sections in which you have a particularly insightful comment. These notes will be helpful to refer back to when discussing articles in class. Skim ActivelyWhile you’re not reading every single word, you’re also not just reading headings. Read the first and last sentences of each paragraph. Scan your eyes over each paragraph to see if there are important supporting points or keywords. After skimming a section, take a moment to summarize what you skimmed – jotting down brief synthesis notes can help, although they won’t be as extensive as the notes from the materials you read closely. Writing down broad questions you have can help, too – they may be questions you want to raise during the discussion or in your seminar paper. Whether you are reading closely or skimming actively, you should ask yourself questions as you read. Constantly challenge yourself: What is the point of this passage? What is the author trying to convey? How does this connect to my own scholarship? How does this connect to the larger body of work in my field?

Graduate school life is super busy, and many grad students find themselves getting around to their reading late at night, after they’ve spent a full day in the lab or classroom. If your lids are feeling heavy, put the article down and go to sleep! You’re not going to absorb the information in a meaningful way, while at the same time your cutting into precious time that could be spent on other more enjoyable aspects of your life. A double-whammy of wasted time and missed opportunity! Set time aside to take care of yourself. Sleep is important, so make sure you get enough of it! In the end, it’s better to have meaningfully consumed a smaller portion of your reading than it is to have read it all and retained nothing.

One of the perennial questions I get about reading in graduate school is “should I use electronic resources, or hard copies?” I think this is a personal question that depends on your individual preferences and desires, but in so doing highlights an important point: you’ve got to figure out what works for you. Some students have a difficult time concentrating when staring at lighted electronic screens; others prefer the ease of annotating paper copies. On the other hand, all that printed paper can be an organizational nightmare that for some can be a distraction in itself. Whether you like reading real paper or the electronic version, try different options and see what ‘clicks.’ Likewise, try switching up the environment where you read to find the best fit:

Getting through your reading doesn’t just take steely perseverance, it also takes common sense and a personal strategy that works for you.

Tags: coursework, grad student, graduate school, phd, reading, survival strategies October 15th, 2014 “Should I Go to Graduate School?”If you’re an undergrad or recent college graduate, you’re probably asking yourself this question: “should I go to grad school?” The idea is simultaneously tantalizing and terrifying. Along with the promise of prestige and expanded career opportunity comes the risk of added debt, a delayed start to your career, or wasted time. Here are five questions you should ask – and answer – before deciding whether or not graduate school is right for you.

Graduate school can be expensive. A report (pdf) by the New America Foundation shows that the median debt of a graduate degree holder is about $57,600, while the 75th percentile of borrowers owed over $99,000. The tuition for professional master’s degrees in top programs at private universities can be well over $40,000 a year and there is often little non-repayable financial aid available. What are the median salaries in the field you want to enter with your degree? How much money can you expect to make after graduating? And are you going to be able to comfortably repay the debt you incur? Even if you enter a fully funded PhD program, you will be out of the workforce for at least five years – and increasingly, six to ten years. Outside grad school, that’s time you could spend accumulating work experience and moving up the ladder (in addition to earning more money and saving for retirement). Six years is enough to make you mid-career in many fields, where you’ll be earning a great deal more than a grad student stipend. Ask yourself: Is it personally worth it to incur the expense or forgo those opportunities in order to earn your graduate degree?

Ultimately, a graduate degree is designed as a training program for some kind of career field. The end goal is for you to get a job in the field and build a career based on your newly acquired skills. But if you can already do that without a graduate degree, why spend the time and effort? I like the way Alison Green puts it: “Grad school makes sense when you’re going into a field that requires or significantly rewards a graduate degree.” Do the people who are currently doing what you want to do have graduate degrees? Is there a ceiling to your progression in that career if you don’t have an advanced degree? If so, where is it? The corollary to this question is to ensure that the degree you plan to obtain is actually going to lead you to the career field you want. Do some research: what kinds of graduate degrees, if any, do the people in your desired career field have?

Graduate programs – particularly PhD programs – are designed to be intense, immersive experiences. Unlike college, graduate school is not the time to explore new interests; instead, you’ll be hyper-focused on the area you choose to study. But remember that the graduate treatment of a subject can be quite different than what you were exposed to as an undergrad. As a master’s student, you will dive into the ‘nitty gritty’ in addition to spending a great deal of time mastering research methods and other analytical tools. If you don’t have a clear goal in mind, the passion you felt for a subject as an undergrad can quickly wear off. On the other hand, if you know why you’re there you may find yourself instilled with new-found drive and motivation: many of these students find that they enjoy their graduate experience more than undergrad. If you’re not entirely sure of what you want to study and why you want to study it, remember that you don’t have to attend grad school to continue your intellectual growth. You can attend lectures at nearby universities, take classes as a non-degree student, or simply go to your local library.

If this question makes you think, stop now! There are so many things you can do after college that don’t involve getting a graduate degree. According to the Census Bureau, only about 11.5% of the U.S. population over the age of 24 has a graduate degree. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the unemployment rate for those with only a bachelor’s degree is a mere 4%. It’s a myth that you can’t find a job without a graduate degree. The vast majority of the American workforce has never attended grad school and never will.

Graduate studies can be a wonderful experience – intellectually stimulating, challenging, eye-opening – but the environment can also be intense. Given the pool of students around you, graduate school can take on a pressure-cooker atmosphere, and while the rewards are (usually) high, the demands of your program (and accompanying stress) will be significant. The demands of grad school will also limit, at least to some extent, your ability to do other things. If there is something that you really wanted to do after undergrad – say, travel the world, teach abroad, move to a new city – with few exceptions, you should do that first so that you can feel settled once your start your program. The last thing you want to do is find yourself totally overwhelmed by other interests in your first year of grad school. Tags: academic careers, after college, career choices, graduate school, phd, survival strategies |