Accessibility of Abortion in Canada: Geography as a Barrier to Access in Ontario and Quebec

By

2016, Vol. 8 No. 06 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

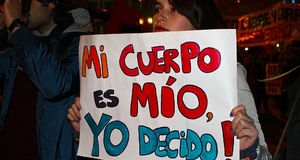

In Canada, a point of national pride has often been our publicly funded health care system. Its pillars of universality, accessibility and comprehensiveness exemplify the Canadian identity as being inclusive and progressive. However, it is important to look beyond the big picture and delve into how our health care system actually measures up to these standards in the lives of Canadians. Canada is often seen as a global leader in gender equality and sexual and reproductive rights (Action Canada for Sexual Health and Reproductive Rights [ACSHR], 2015a); we are one of the few countries in the world with no laws restricting abortion (United Nations, 2001). Despite this, the health care system’s realization of a woman’s right to abortion in real life is not necessarily congruent with the legal and moral stance of our country. Canadian women may have the right to choose to have an abortion, but this is not equivalent to having access to abortion procedures. This essay will explore how the current landscape of abortion accessibility is at odds with Canadian law established twenty-seven years ago. Specifically, it will focus on the ways in which many women in both Ontario and Quebec face inadequate access to abortion services due to their geographic location, and the repercussions of this lack of access. BackgroundIt is important to have at minimum a brief knowledge of the history of the struggle for abortion rights in Canada. This will help one understand the current landscape of abortion services and the value in critically assessing them. In 1892, Canada’s first Criminal Code was passed, criminalizing both abortions and contraceptives. Many women continued to seek abortions however they often posed a dangerous risk to a women’s health and well-being as they were illegal and ungoverned procedures (CBC News, 2009).The death rates estimated of women as a result of illegal and unsafe abortions were incredibly high throughout the first half of the 20th century in Canada, with an estimated 4,000 to 6,000 deaths between 1926 and 1947 alone (Cross, 2009). In 1969, amid government lobbying, abortion was decriminalized under certain circumstances by the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Therapeutic abortion was introduced, allowing a woman to legally obtain an abortion in an approved hospital if a Therapeutic Abortion Committee of three doctors agreed that continuing her pregnancy would put her health or life at risk (Cross, 2009). The result of this provision was that only a miniscule percentage of abortions were approved and accessibility throughout the country was inconsistent. It took another nineteen years and the singular efforts of Dr. Henry Morgentaler, Canada’s most renowned pro-choice advocate, to change this. On January 28, 1988 the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the therapeutic abortion law (section 251 of the Criminal Code) as unconstitutional in their ruling of R. v. Morgentaler. The Supreme Court found that it violated section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by infringing on a woman's right to "life, liberty and security of person” (CBC News, 2009). The 1988 ruling established access to safe, legal abortion as a constitutional right for women (Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada [ARCC], 2011). It also signified that abortion would be treated as any other medically necessary procedure, to be held to the standards of the Canada Health Act (Cross, 2009). Despite the legal ramifications of the R. v. Morgentaler decision, abortion services across the country currently exist in varying states, many of which overtly contradict the requirements of the Canada Health Act and section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms as it pertains to women’s reproductive freedom. Various examples can be made to demonstrate that the provision of abortion services in Canada does not reach any of the five main criterion of the Health Act: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility (Canada Health Act, 1985). However, in exploring geographic location as a barrier to the equitable access of abortion, this essay will focus on the divergence of abortion services from the principles of universality and accessibility. As established by the Canada Health Act, universality is the notion that all insured residents are entitled to the same level of health care. Accessibility exists when all insured persons have reasonable access to health care facilities (Canada Health Act, n.d.) This report will demonstrate that the lack of accessibility of abortion providers in rural and remote areas of Ontario and Quebec denies the achievement of universality in Canadian health care. Geographic location exists as a barrier to the accessibility of abortion throughout Canada, in provinces and territories beyond Ontario and Quebec. Only 15.9% of Canadian hospitals offer abortion services, and the majority of these hospitals are located in urban centres within 150 kilometers of the American border (Shaw, 2006). Specialized clinics that legally provide abortions exist in seven provinces (Sethna & Doull, 2013, Table 1), but similarly, these clinics are mainly located in urban centres (Sethna, 2012). While women living in southern Canada near urban centres are well-placed to access abortion services, women almost anywhere else in the country are not. Travel is the largest barrier Canadian women experience in accessing abortion services. In Prince Edward Island there are no hospitals or clinics that provide abortion services, and requests to receive an abortion in another province funded by P.E.I.’s provincial health care are most often denied (negating the CHA criterion of portability) (Reid, n.d.) Nunavut and Yukon each have only one provider of abortion services; the Northwest Territories and New Brunswick, two. Labrador does not have any abortion service providers (Reid, n.d.) There is countless more data that outlines the disproportionate dispersal of abortion services and the amount of travel necessary for some women to access them in Canada. The need to travel can be further compounded by financial strain related to the costs of transportation, accommodation, childcare, elder care, lost wages, and possibly even the procedure itself (ACSHR, 2015b). For teenagers or women who are poor, live in an abusive relationship, or are victims of incest, travel is especially difficult if not impossible (ARCC, 2005b). For these reasons, travel is the largest barrier Canadian women experience in accessing abortion services (ARCC, 2005a). Analysis: The Barrier of Geographic Location in Ontario and QuebecOntarioGeographic location is a major barrier to accessing abortion services in Ontario, specifically for women living in the northern half of the province. Only 17% (a total of thirty-three) of Ontario’s hospitals provide abortion services, and nearly all of these hospitals are concentrated in Toronto and southwestern Ontario. Of the large expanse of the province that exists north of Ottawa, there are only five hospitals that provide abortion services. Further, only one of these five is located north of the Trans-Canada Highway (Shaw, 2006). This means that the reproductive health needs of women in an immense area of the province are inadequately met. Ontario’s abortion services are currently undergoing a shift in model; where hospitals were once the primary providers of abortion services, specialized clinics are now heavily relied on to meet the needs of Ontario women (Kaptein, 2012). Between the short span of three years, from 2003 to 2006, the number of Ontario hospitals providing abortion services decreased by eleven (Shaw, 2006). This could have been a result of budget cuts, the shortage of health care professionals with abortion training, or the merging of publicly-funded hospitals with Catholic hospitals (Shaw, 2006). Regardless of the reason, it means that this shift (which minimizes the role of hospitals in abortion services), disadvantages women from rural, remote, and northern regions whose location prevents them from easily accessing urban clinics and are in need of hospital providers in their communities. Of the eleven abortion clinics in Ontario, nine are located in the Greater Toronto Area, the remaining two being in London and Ottawa. Abortion clinics do not exist far from the Canada-U.S. border or far from urban centres (ARCC, 2015), and are therefore not adequate providers for women living in northern and rural Ontario. As private abortion clinics only exist where large populations are sure to sustain them, a health care model that largely relies on these clinics to meet the abortion needs of its entire province is not only irresponsible, but inequitable. Many women must travel out of their communities to access abortion services which are offered only in a small percentage of hospitals. The hospitals that offer abortion services thus become overrun, causing long wait times. Ontario has the largest population of all provinces and too few hospitals providing abortion services, making it home to the three hospitals with the longest wait times for abortion procedures Canada wide. The providing hospitals in Sarnia, Peterborough, and Ottawa each have wait times of up to six weeks (Shaw, 2006). Long wait times in hospitals lead many women to travel to abortion clinics instead (Shaw, 2006). However, abortions performed in at least three of the eleven clinics in Ontario are only partially funded (ARCC, 2015), thus increasing the expenses to pay for the abortion as well as the travel costs. Besides disadvantaging women in northern Ontario by forcing them to travel outside their areas of residence to access abortion services, the inadequate accessibility of hospital-provided abortions also creates temporal and financial barriers to safe abortions. QuebecQuebec is considered the province which offers the best accessibility to abortion services (Shaw, 2006). In terms of physical availability of providers, Quebec has the most service delivery points in the country thanks to its two-tier system of hospitals and Local Community Service Centres (CLSC) which work together to meet the abortion needs of its population. In Quebec there are thirty-one hospitals and eighteen CLSCs that provide abortion services (Shaw, 2006). Further, these service delivery points are better distributed than they are in any other province (Dunn et al., 2010). This is because Quebec’s model assures a regional breakdown of funds so that all seventeen administrative regions are serviced by at least one provider of first-trimester abortions (Dunn et al., 2010). Despite Quebec’s success in furthering the accessibility of abortion services, geographic location still exists as a barrier for women in some areas of the province. With thirty-one service delivery points, Quebec may outnumber the rest of Canada in their delivery of abortion services, but this amount still constitutes less than 25% of all hospitals and CLSCs in the province (Dunn et al., 2010). As a simple procedure that any hospital with an obstetrics ward can be equipped for, this number is minimal (Shaw, 2006). The gaps in access can be seen in the southern regions of Estrie, Outaouais, and Chaudiere-Appalaches, where there is only one provider of abortion services for each region (Québec Portail Santé Mieux-être, n.d.), despite populations of up to 419,755 inhabitants (Institut de la Statistique du Québec, n.d.). More critically, because the majority of hospital providers are concentrated in southeastern Quebec, northern communities are dramatically disadvantaged in accessing abortions. The vast regions of Nord du Quebec and Cote Nord are each only serviced by two providers. This means that a woman from the remote northern town of Kuujjuaq in Nord du Quebec must travel 989 kilometers (more than half the length of the province) to access abortion services from the nearest provider, the CLSC located in Chibougamau. Women that cannot access abortion services from the hospitals and CLSCs within their areas of residence are in need of accurate and reliable information about where they can access these services. Even if a hospital or CLSC does not provide abortion services, they are still expected to be able to direct a woman to an appropriate provider. However, a study undertaken by Canadians for Choice and Fédération du Québec pour le Planning des Naissances discovered that only 58% of these institutions in Quebec were able to direct a woman to an appropriate abortion services provider (Dunn et al., 2010). The lack of reliable sources of information presents another level of barrier in the accessibility of abortion for women disadvantaged by geographic location. Repercussions of Inadequate Access Caused by the Barrier of Geographic LocationWhen women cannot access abortion services within their areas of residence there are serious implications for their physical, emotional, and financial well being. For one, abortion is an extremely time-sensitive procedure, making prompt access to abortion services essential to a woman’s physical health (Kaptein, 2012). Abortions performed at lower gestational age lower the risk of complications (Kaptein, 2012); acclaimed physician and pro-choice advocate Dr. Henry Morgentaler once stated, "Every week of delay increases the medical risks to women by 20 percent" (ARCC, 2011). Since prompt access is obstructed when women must take the time to locate an appropriate provider, take time off work, gather funds, arrange for childcare or elder care, transportation and accommodation, and physically travel to another location, women’s physical well-being is put at risk by geographically inaccessible abortion services. Another dangerous risk to women’s physical health arises when women do not access safe and legal abortions at all. Research has shown that the further a woman must travel in order to obtain an abortion, the less likely she is to get one (Shelton et al., 1976). When the distance is too far, the cost too expensive, and the trip ultimately impossible, women with unwanted pregnancies may attempt to self-induce an abortion. This is very dangerous as it can lead to severe medical complications including infection, infertility and death (Shaw, 2006). While no Canadian statistics exist regarding the frequency of self-induced abortions or their death toll, it is accepted that they are not as uncommon an occurrence as they should be in a country in which abortion is legal (Shaw, 2013). Despite the fact that abortions in Canada are legal, safe, and generally simple medical procedures (with less risk involved than childbirths), women that find abortion services geographically inaccessible face serious detriment to their physical health, because the needs of their pregnancies are not met (Raymond et al., 2012). Travel is the single biggest barrier to accessing abortion services in Canada (ARCC, 2005a). The burden of travelling to receive geographically inaccessible abortion services is compounded by the financial, emotional, and psychological strain it puts on women. In addition to the fact that women may have to pay out of pocket for their procedures or certain fees in some private clinics in Ontario and Quebec, those that choose to access abortion services by travelling will incur numerous other costs such as transportation fare or gas, accommodation, lost wages, and child or elder care. These costs can be doubled or tripled, as women are often required to attend a preliminary consultation at the providing clinic or hospital as well as a follow-up after the procedure, necessitating multiple trips (Shaw, 2006). Such expenses further limit the accessibility of abortion services for women that are geographically removed from a providing clinic or hospital (ARCC, 2005b). Women in the Montréal region of Quebec benefit from a policy that allows regional hospitals to arrange for all procedural, transportation and accommodation costs if they are over the gestational limit of the providers in the region and must travel elsewhere (Shaw, 2006). However, this policy does not apply to all the women living outside of Montréal, many of whom pay out of their own pockets just to access first-trimester abortions. The limited reaches of this policy once again underlines the immense inequity of abortion access, especially as pertains to geographic location as a barrier. Lastly, the financial burden of travel is likely a key factor in why the geographic inaccessibility of abortion is shown to disadvantage “the poorest, youngest and least sophisticated women” the most (Shelton et al., 1976). For many women, the need to travel to access abortion services presents a psychological and emotional strain. The planning involved in such a trip can cause stress surrounding lack of finances, having to locate an appropriate provider, and making life arrangements for the time away (ARCC, 2005b). Even after planning and travel, the vulnerability and stress associated with the need to navigate an unfamiliar environment can be enough to deter some women from accessing abortion services that are far away (Shelton et al., 1976). This emotional and psychological unrest can be added onto already existent emotional distress related to carrying an unwanted pregnancy. For teenagers, women in abusive relationships, and victims of incest, the need to travel makes accessing an abortion even more difficult and can result in an even harsher impact on emotional and psychological health (ARCC, 2005b). Finally, the geographic inaccessibility of abortion services means that post-abortion support meetings will likely be inaccessible to those women far removed from their providing hospital or clinic. Given the emotional hardship some women experience after having an abortion, these meetings are meant to support a woman in her mental and emotional health. For women without providers in their area, the lack of post-abortion support is just another way in which their emotional and psychological health is negatively impacted. Comparison of Abortion Accessibility in Ontario and QuebecWhile women in both Ontario and Quebec face inadequate access to abortion services because of their geographic location, there are insights to be gained from comparing each province’s approach. Despite the faults that have been outlined, it is clear that Quebec’s model is more effective in limiting the barrier that geographic location plays. One strength of Quebec’s delivery of abortion services is in it’s quantity of providers. The inclusion of CLSCs as a government institution that can legally provide fully-funded abortions alongside hospitals augments the accessibility of the service considerably. Ontario and Quebec have a comparable amount of hospitals that provide abortion services, thirty-three and thirty-one respectively, but Quebec’s additional eighteen CLSCs widen the geographic scope of its access. In comparison, the shortage of Ontario hospitals providing abortion services has resulted in a reliance on private clinics to meet demand. As discussed, private clinics in Ontario do not limit the barrier geographic location plays in accessibility because of their concentration in southern urban centres. Ontario’s shortage of hospital providers has also resulted in unacceptably long wait times of up to six weeks, while Quebec’s institutions average a wait time of ten working days (Dunn et al., 2010). A second strength of Quebec’s model of service delivery exists in its regional breakdown of funding. By dividing funds between Quebec’s seventeen regions in a way that assures that each one will have at least one hospital or CLSC that provides first-trimester abortions, Quebec does succeed in improving geographic accessibility. Finally, the accessibility of abortion services in Quebec seems to be resultant of a stronger government commitment towards the reproductive rights of women as well as a historically strong and active women’s right movement. ConclusionGeographic location is a barrier to the accessibility of abortion services in both Ontario and Quebec. This is because the concentration of abortion providers in southern regions of each province and in urban centres disadvantages women living in northern and rural areas. This geographic inaccessibility has negative implications on the physical, emotional, and psychological well-being of women, some of whom will not access abortion services at all, choosing instead to self-induce abortion or to continue the pregnancy. Neither of these are acceptable options for a woman in need of a safe, legal abortion, and in a country in which this is a constitutional right. The geographic inaccessibility of abortion services in Canada infringes on women’s Charter right to life, liberty and security of the person as established by R. v. Morgentaler in 1988, and diverges from both the accessibility and universality principles of the Canada Health Act. Officially, such breaches to the Canada Health Act by provincial governments would interfere with its qualification for the Canada Health Transfer (Canada Health Act, 1985). However, federal governments have not reacted. Pressure must be put on the current government to hold provinces and territories to account for the neglection of women’s right to reproductive freedom. If Canada is the inclusive, progressive nation many hope it is, a struggle will be made to unite women’s legal rights with their provision in real life. ReferencesAbortion Rights Coalition of Canada. (2015). List of Abortion Clinics in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.arcc-cdac.ca/list-abortion-clinics-canada.pdf (a) Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. (2005). Position Paper #6: Training of Abortion Providers / Medical Students for Choice. Retrieved from http://www.arcc -cdac.ca/postionpapers/06-Training-Abortion-Providers-MSFC.PDF (b) Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. (2005). Position Paper #7: Access to Abortion in Rural/Remote Areas. Retrieved from http://www.arcc-cdac.ca/postionpapers /07-Access-Rural-Remote-Areas.PDF Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada. (2011). Position Paper #1: Abortion is a “Medically Required” Service and Cannot be Delisted. Retrieved from http://www.arcc -cdac.ca/ postionpapers/01-Abortion-Medically-Required.pdf (a) Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights. (2015). Background Information and Recommendations for Canada on Key Issues Related to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Foreign Policy. Retrieved from http://www. sexualhealthandrights.ca/ wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Action-Canada- Election-2015-Global-briefs.pdf (b) Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights. (2015). Opinion: Canada’s Abortion Myth. Retrieved from http://www.sexualhealthandrights.ca/opinion -canadas-abortion -myth/ Canada Health Act (1985, c. C-6). Retrieved from the Justice Laws website: http://laws- lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-6/ Canada Health Act. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.canadian-healthcare.org/page2.html CBC News. (2009, January 13). Abortion Rights: Significant Moments in Canadian History. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/abortion-rights -significant- moments-in-canadian-history-1.787212>. Cross, P. (2009). Abortion in Canada: Legal but Not Accessible, A YWCA Canada Discussion Paper. Retrieved from https://www.ywcatoronto.org/upload/ advocacy-2009 %20policy%20abortion%20in%20Canada.pdf Dunn, M., Quirion, M. E., Parent, N., Jenicek, A., LaRue, P., Grabowiecka, S., Charbonneau, J. (2010). Focus on Abortion Services in Quebec. Retrieved from http://www.fqpn.qc.ca/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ResearchCFCFQ PN2010.pdf Institut de la Statistique du Québec. (n.d.) Statistical profiles by region and geographical RCMs. Retrieved from http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/profils/region _00/region_00_an.htm Kaptein, S. (2012). Access to Abortion Services in Ontario. Ontario Health Promotion E-Bulletin, 2012(742). Retrieved from http://www.ohpe.ca/node/13022 Québec Portail Santé Mieux-être. (n.d.) Finding a Resource Offering Abortion Services. Retrieved from http://sante.gouv.qc.ca/en/repertoire-ressources/avortement /?triPar= service&ch_service=3&ch_nom=&ch_code=&ch_rayon=0&choix Territoire=region&ch_choixReg=8&bt_submitCode=Start+search&mod=1 Raymond, E. G., Grimes, D. A. (2012). The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Abstract retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmed/22270271 Reid, M. S. (n.d.) Access by Province. Retrieved from http://www.morgentaler25years. ca/the-struggle-for-abortion-rights/access-by-province/ Sethna, C., Doull, M. (2013). Spatial disparities and travel to freestanding abortion clinics in Canada. Women's Studies International Forum, 38, 52-62. Sethna, C. (2012). Travel to Access Abortion Services in Canada. Retrieved from http:// socialsciences.uottawa.ca/sites/default/files/public/research/eng/documents/CSethna_WorldIdeas.pdf Shaw, J. (2013). Abortion in Canada as a Social Justice Issue in Contemporary Canada. Critical Social Work, 14(2). Shaw, J. (2006). Reality Check: A Close Look at Accessing Abortion Services in Canadian Hospitals. Retrieved from http://www.sexualhealthandrights.ca/wp-content/ uploads/2015/09/reality-check_EN.pdf Shelton, J. D., Brann, E. A., Schulz, K. F. (1976). Abortion Utilization: Does Travel Distance Matter? Family Planning Perspectives, 8(6), 260-262. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2001). Abortion Policies: Afghanistan to France. New York City, NY: United Nations Publications. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Health Science |