|

Featured Article: World War II in the United States Colony of the Philippines: Beyond the Bataan Death March and Douglas MacArthur

World War II ranks among the deadliest military conflicts in history. From 1939-1945, the estimated number of casualties worldwide exceeded 60 million. The United States suffered military fatalities in excess of four hundred thousand, and the Philippines, an archipelago in Southeast Asia and an American colony from 1898 to1946, endured horrifying atrocities such as the Bataan Death March. One hundred thousand Filipino civilians (the majority being women, children, and the elderly), were ultimately slaughtered by Japanese Marines during the sack of Manila. By March of 1945, this cosmopolitan capital city, once known as the "Pearl of the Orient Seas," lay in ruins.

There has been a great deal of research on WWII in a variety of fields. However, there remains a void in perspectives pertaining to the experiences of the Filipino natives and foreign minorities who resided in the Philippine colony during the Japanese occupation (1942-1945). This paper addresses this breach by advancing the argument that the suffering endured by Filipinos during the latter part of the Japanese occupation paralleled that of American troops in the region. Moreover, this study contends that the Philippine Commonwealth experienced greater hardships during the war because of its status as a U.S. protectorate, and that the conflict on Philippine soil was never intended to be a "War of Annihilation," a thesis advanced by Zeiler and others; warfare escalated into extermination only when Japanese defeat was imminent.

The suffering endured by Filipinos during the Japanese occupation paralleled that of American troops in the region. Moreover, the Philippine Commonwealth experienced greater hardships during the war because of its status as a U.S. protectorate.

In the decades following the 1940s, the most extensive studies concerning the war in the Philippines have involved the Bataan Death March and biographies on General Douglas MacArthur; narratives surrounding the American liberation being the most widely available. However, there is so much more to this story. Scholarship involving WWII's impacts upon the Philippine Commonwealth is sparse, since studies have largely centered around the American or European experience. By emphasizing the lost voices of local Filipinos, this paper will provide a unique perspective on the nature of the conflict in Southeast Asia. This from-the-ground-up study will highlight the bravery and immense sacrifices of colonized Filipinos during the pivotal loss and subsequent recapture of the Philippine Islands from the hands of the Japanese. This scholarship offers the opportunity to transcend the fabled Douglas MacArthur legend and tales of the Bataan Death March, and illuminates lesser known, less glamorous aspects of WWII in Southeast Asia. In the process, the widely-circulated and popularly accepted theory that a war of annihilation was the definitive Japanese objective will be called into question.

Historians have presented profoundly differing views of WWII. Past accounts by leaders and elites "who made headlines" and whose "deeds survived as historical truth" have dominated the research on WWII. Biographies on General Douglas MacArthur by Carol Morris Petillo and Michael Schaller are prime examples of notable works in the "great man" vein. However, there has been a perceptible shift in recent years to uncovering the perspectives of everyday individuals. This progression brings to the forefront the experiences of previously marginalized groups, such as the Filipinos and foreign nationals who resided in the Philippines during the Japanese invasion; they were the masses who bore witness to the Japanese occupation firsthand, who fought and died in defense of American liberty on foreign soil. This welcome trend in historical scholarship offers an increasingly comprehensive and holistic picture of the WWII experience from the ground up. For example, the shift towards the common man perspective is apparent in the work of Juergen Goldhagen, which delves into the experiences of four ordinary foreigners "caught in Manila by the war."

Narratives like Goldhagen's represent an antithesis to the Good War hypothesis that endorsed the notion that WWII was "noble and heroic," an idea that has dominated historical scholarship since the 1940s, and persists in political rhetoric to this day. This "powerful idea based on myth, arrogance, and sanitizing the record," is unfortunate, for it trivializes the lasting scars suffered by war-torn victims, and blunts the invaluable lessons that may be gleaned from such historical events. In idealizing WWII, the Allies were customarily portrayed as champions for democracy in the conflict between good and evil. This portrayal is so pervasive that it still permeates present political discourse.

The depiction of WWII as the Good War reached its peak at the end of the twentieth century, when a new theory emerged: the War of Annihilation. This evolution from Good War to Annihilation is exemplified in Annihilation by Thomas Zeiler, which advanced the premise that WWII was an outright race to destroy the enemy's capacity to wage war; where lines between civilians and soldiering were blurred. Zeiler claimed that the objective of the war was to "eliminate the enemy threat physically, ideologically, and totally." While this was not entirely accurate when examined in light of the Japanese occupation in the Philippines, it nonetheless presents a sobering picture.

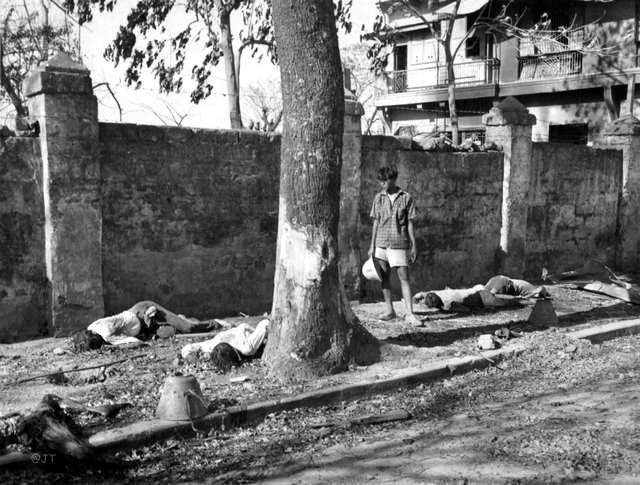

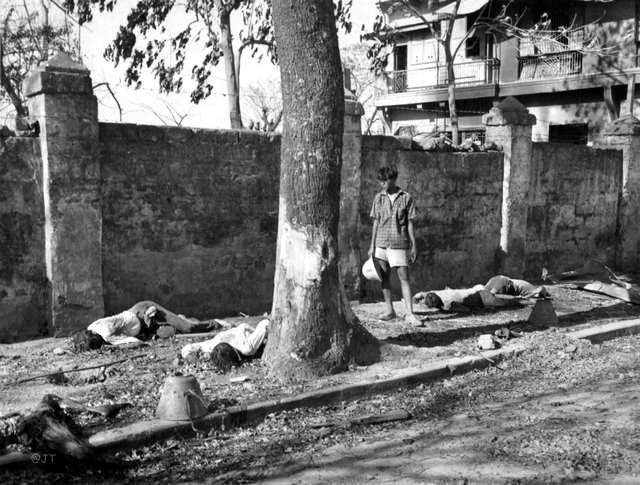

February 9, 1945. Colorado Street, Ermita, Manila. Photo: John Tewell

Prized by the U.S. for its strategic location in the Pacific Ocean, and forming what MacArthur called "a key or base point of the U.S. defense line," the Philippines presents a natural barrier between Japan and the abundant resources of East and Southeast Asia. An archipelago comprising over seven thousand islands, the Philippines is situated east of Vietnam, approximately seven hundred miles from Formosa, Taiwan. With a tropical-marine climate and a land area of 115,124 square miles, the Islands were awarded to the U.S. in 1898, at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War.

A year after acquiring the Philippines in 1898, America instituted a system of self-governance in the Islands to grant the Filipinos political experience and eventual independence. This experiment limped along, because U.S. intervention never truly ceased. Filipinos were allowed participation in the administration of the Philippines, but U.S. citizens retained all the substantial policy-making positions.

In 1935, the Philippines gained Commonwealth status under President Manuel Quezon, though it remained in every respect a U.S. colony, with Douglas MacArthur serving as Military Advisor to President Quezon and field marshal of the Philippine Army prior to the outbreak of WWII (1935-1941). Under American colonial rule, the objective was the "political education on democratic government" of the Filipinos, along with economic preparation for complete independence; however, this was primarily a farce, and dialogue of independence was biased with an eye towards preserving American self-interests and Philippine dependency upon the U.S. For example, constitutional provisions, such as the Public Land Act, limited the exploitation of Philippine lands and other natural resources to Philippine and American citizens. The inclusion of Filipino interests in the Public Land Act was meant to pacify the elite classes and garner their support for continued American occupation. From the point of view of Japan's Imperial Government, the Public Land Act translated to a slight against Japanese nationals, because it essentially disenfranchised over twenty thousand Japanese who were residing in the Philippines by 1935. Such policies were aimed at bolstering U.S. economic interests in the Philippines.

By 1941, Japan was blistering from several perceived U.S. insults. Its oil inventories were in dire straits due to American-led global oil embargoes. For the Japanese Government, which had been suffering severely from fuel shortages, the Philippine sugar fields represented the potential for an alternative alcohol fuel source and butane for aviation fuel. The need for substitute fuel sources had hit a critical stage if Japan were to sustain the war effort. At stake in the Philippines were vast natural resources in the form of rice, coconut, sugar cane, hemp (locally known as abaca), timber, petroleum, cobalt, silver, gold, salt, and copper--export industries which were thriving thanks in large part to the generous introductions of American capital.

Japan also viewed the Philippines as a golden opportunity for retribution against the U.S. for the pervasive disenfranchisement policies it promoted in the Philippines, and the prohibitions it championed against Japan globally. As an added bonus, Japan recognized that its occupation of the Philippines would deal America a grave economic blow, since the U.S. imported the bulk of its rubber, sugar, and various agricultural products from the Philippines.

It cannot be ignored that the Philippines was a logistical trading hub, since the Islands were advantageously located in close proximity to the South China Sea, Philippine Sea, Sulu Sea, Celebes Sea, and the Luzon Strait. This was a fact of which both Japan and the U.S. were keenly aware. From the Japanese perspective, its invasion of the Philippines served multiple purposes: it was a blatant affront meant to humble the U.S. and impress upon the Americans the sheer might and cunning of the Japanese military; and, by 1941, the Philippines was a trophy ripe for the picking. For nearly half a century, the Commonwealth had thrived under the protection of the powerful United States of America. What is more, by the outbreak of WWII, the Philippines had benefited economically from its colonial ties to the U.S. for many decades. This had guaranteed a measure of stability and lawfulness, with corruption kept at a minimum, which in turn fostered a climate of legitimacy that attracted private enterprises to the archipelago. Because of the inflow of U.S. financial subsidies into its military infrastructure, the Philippines possessed a fairly modern string of tactically placed naval bases, airstrips, oil tank fields, and roadways that wound through the Island from Cavite to Cebu, from Zambales to Manila--fortifications that the Japanese coveted.

For Japan, the Philippines was too tempting a prize to resist. On December 8, 1941, Japan launched its "onslaught against the Philippines" within twenty-four hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The United States Government representatives in the Philippines reacted swiftly, interring Japanese nationals residing in the Commonwealth. Japanese consulates, Japanese schools and office buildings were converted into temporary detention camps. But America's grip upon the Philippines was tenuous at best. The combined forces of MacArthur and the Philippine Army were woefully outmanned, and could not repel the full-scale Japanese assault. As a result, the internment of Japanese nationals proved to be short-lived, for scarcely two weeks later, the Japanese Army seized control of Mindanao in the southeastern Philippines, and all internees were released.

In an effort to rescue Manila from further destruction, on December 26, 1941, Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an "open city," before retreating and abandoning all defensive efforts. It was a calculated move intended to preserve Manila's historical landmarks and spare its civilians. This strategy was effective, and damage to infrastructure was minimal, since the incoming Japanese forces, for the most part, had respected wartime protocols. Soon after the Japanese took possession of Manila in January 1942, life continued on as before and a sense of normalcy gradually returned to the city.

Following MacArthur's retreat, while American and Filipino POWs were staggering across Mariveles on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula in what came to be known as the infamous Bataan Death March, thousands of American civilians were imprisoned in internment camps in Manila. The U.S. internees in the Philippines represented the largest group of American civilians to experience "enemy occupation" during WWII.

During the early years of the occupation, the University of Santo Tomas internment camp was not much of a prison; internees were granted "passes" to visit family on the outside. Some passes were a month long, requiring only periodic check-ins. This changed as the war progressed and Japanese camp administrators grew increasingly fearful of subversives.

While German, Italian, and Swiss nationals were treated as allies by the Japanese and were exempted from internment, Americans were not. Ironically, the internees may have been the fortunate ones, for although they suffered hunger, overcrowding, and maltreatment as the war wound to a close, life outside the confines of the camps eventually proved to be much worse. German Jews also fared much better in the Philippines than in Europe, because the Japanese did not condone the genocidal, anti-Semitic tendencies of their Nazi counterparts. Twelve hundred Jews migrated to the Philippines to escape the Nazis from 1937-1941, and in many ways, Jewish citizens received far better treatment at the hands of the Japanese than the Filipinos.

There was no policy of annihilation during the Japanese occupation; foreigners were granted the freedom to come and go. Internees even managed to aid the resistance, "running money and supplies" to guerrilla forces. Contrary to the War of Annihilation theory which espouses that, "civilians are military targets and not immune from warfare," in the Philippines, there was a definitive distinction between Japanese treatment of civilians and POWs. POWs were viewed as fair game, and were subjected to torture at the hands of interrogators. The Japanese exploited POW labor in sugar and cotton plantations in Pampanga and Batangas. Civilians who were caught aiding and abetting POWs or guerrillas, forfeited their civilian immunity and were susceptible to the same abuses.

For the Filipinos, the Commonwealth had merely swapped out one occupier for another. In spite of the Co-Prosperity Sphere propaganda, Japanese occupation of the Philippines simply masked Japanese Imperialism on the European model. Under the Imperial Army, schools and universities reopened, albeit with a revised curriculum that included Japanese language. Even movies and vaudeville shows were permitted. The Japanese allowed a limited number of American films to be shown in theaters, provided the subject matter steered clear of wartime topics. The Jai Alai games, a favorite national pastime, continued uninterrupted. Agriculture and animal husbandry were also encouraged. There were just as many stories of kind gestures and mutual cooperation among Filipinos and Japanese, as there were stories of atrocities at the end.

The role of the Roman Catholic Church in the life of the average Filipino cannot be overstated. The Church served as a defender of civil liberties, social justice, and political and human rights; it was often the social center of community life as well, and provided physical, emotional, and psychological refuge in turbulent times. To this day, the Philippines remains the only country in Southeast Asia with an overwhelmingly Christian population. During the Japanese occupation, Filipino citizens were granted the freedom to worship, and church services on Sundays resumed. Thus for the average Filipino citizen residing in the capital city of Manila, life during the first two and a half years of the occupation was somewhat similar to how it had been before the war.

The Japanese tried very hard to win over the Filipinos. However, they did not tolerate dissention. If a household was caught with a short wave radio, which were forbidden, it was not uncommon for violators to be hauled off to Fort Santiago, an old Spanish fortress at the entrance of the Pasig River, never to be seen again. Discipline was rigorously enforced by the High Command. The Japanese officers disliked lawyers; they did not tolerate arguments, and demanded strict obedience from military and civilian subordinates. Generally, as long as the populace cooperated with officials, the Japanese treated Filipinos fairly and were respectful of local customs and traditions.

From an economic perspective, the Imperial Government recognized that its conquest of the Philippines placed into Japan's possession an agricultural country that could be brought to self-sufficiency, with minimal economic dependency. In its occupation of the Philippines, Japan gained numerous agricultural resources, including Manila hemp (abaca), which was used for rope and twine and was highly prized by the Japanese. An added windfall to Japan was that it had managed to deprive the U.S. and much of Europe of major sources of rubber, sugar, hemp, and coconut oil. Moreover, the Philippines was also expected to solve Japan's shortages in cotton and aviation fuel, by utilizing "chemical-yielding plants" like sugar cane and castor oil as alternative fuel sources. The goal was that the conversion of sugar to fuel alcohol as a substitute for gasoline, would appease Japan's fuel crises, while launching the Philippines into total fiscal self-sufficiency.

A popular theory is that WWII was a War of Annihilation, the Annihilation premise being that "civilians are military targets and not immune from warfare." This concept stretches the battlefield to encompass towns and private citizens, exterminating enemy populations and destroying resources (such as infrastructure), by brute force. This was not the case with the Japanese occupation in WWII in the Philippines. On the contrary, the situation began to deteriorate two years after the Battle of Midway, as the defeat at Midway slowly shifted the tides in the Pacific against Japan. With each mounting loss, the inhumane treatment of citizens in Japan's occupied territories escalated.

It was only towards the latter part of the Japanese occupation (very late in 1944), as American forces were steadily advancing across the South Pacific, that the hypothesis that Japan had unleashed annihilation tactics upon the Philippines, may hold any merit. By the time the sacking of Manila transpired on the eve of the American-led liberation of the Philippines in February 1945, the Japanese Imperial Army occupiers had been replaced by the Japanese Marines.

There were two Japanese contingents occupying the Philippines during this crucial time: the Imperial Army led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita, and the Japanese Navy (Marines) commanded by Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi. The initial occupation of the Philippines in 1941 was carried out by the forces of the Japanese Imperial Army (Yamashita's men), who were tasked with setting up a government in Manila, and assimilating the local population. It was a commission that for the most part, the Imperial Army conducted with self-restraint and discipline. Yet by the latter part of 1944, the majority of Imperial Army officers, whose soldiers had previously displayed a respectful tolerance of the local populace, who had shown a surprising fondness for children, and who had honored Filipino traditions, had gradually been replaced by the Japanese Marines. The Marines were comprised of Korean and Formosan forces and battle-hardened veterans of the vicious China Campaign. These men were charged with defending Manila against the invading Americans in 1945, as the Japanese Army retreated.

It was unfortunate that the Japanese contingent tasked with holding Manila were a different breed; they were seasoned veterans, desensitized by the brutality of previous campaigns. These Marines spared the Filipinos no mercy. As Japanese defeat loomed, the lines between civilian and military targets evaporated, and annihilation began. Where the Japanese had once been "instructed by their High Command to behave and set an example," irrationality reigned and "they behaved like animals." In a 1946 interview, Major General Charles A. Willoughby (U.S. Army, who served as Douglas MacArthur's Chief of Intelligence), confirmed that the sacking of Manila "was an unnecessary act of fury and brutality" that was carried out "mostly by men from the Japanese Marines, the remaining personnel of sunken ships, the commercial crewmen, and others. The army had retreated towards the hills."

In what came to be known as the Battle of Manila, the Marines spared no compassion as impending defeat translated to sanctioned brutality.As American bombs began to rain down upon the Islands, the Japanese Marines turned savage. There were numerous accounts of babies being tossed in the air and speared on bayonets. Sons were shot in front of their pleading mothers. Those who elected to remain outside the confines of religious institutions or were not interred at the camps, were rounded up by the Japanese in abandoned apartment buildings and houses and burned alive. Women, children, and the elderly were not spared. Anyone who attempted escape by climbing out of windows or scaling walls, were picked off by rifle fire like pigeons in a hunt.

While Filipinos were permitted to continue to worship unimpeded, the Church ultimately proved to be the death knell for many. Blind devotion to the Catholic faith was universal among Filipinos. True to character, numerous Filipinos and mestizos (Philippine-born Spaniards), reacted to the carnage by fleeing into convents, churches, and parochial universities, seeking sanctuary and protection from the indiscriminate raping and murdering. This proved to be an unmitigated catastrophe. On February 7, 1945, the revered De La Salle College saw sixteen Christian Brothers murdered, along with forty-two Filipino and mestizo men, women, and children who had sought refuge inside its hallowed halls. Among them, the beloved Father Leo, an Irishman and Dean of the university and who had spent thirty years in the Philippines. Mothers and daughters were corralled into classrooms, raped, and then shot. At San Augustin Church, the Japanese isolated the Augustinian friars of the convent; six thousand civilians sheltered there. The men were separated from the women and children, and 1,600 were force-marched to Fort Santiago where many met their deaths.

It was devastating to the Filipino spirit to witness the worst atrocities committed by the Japanese during the latter part of the occupation, perpetrated in religious establishments. The desecration of their religious institutions tested Filipino fortitude beyond anything that transpired during the war. It rocked the Filipinos' steady faith deeply, because the violation of Catholic sanctuaries was previously unimaginable. Nothing could have prepared the native Filipinos for such a travesty. The violence was all the more traumatic given that throughout the Japanese occupation--up until the latter part of 1944--the Filipinos in Manila had met with respectful behavior from their Japanese occupiers. For this reason, civilians were caught completely off guard, and had not expected the Japanese to lash out so brutally. But "the more the Japanese were getting a beating, the worse they became."Continued on Next Page »

Andrew Gonzales and Alejandro T. Reyes, These Hallowed Halls, Unknown Binding, 1982.

Antonio Perez de Olaguer, Terror in Manila: February 1945, (Philippines: Memorare Manila Foundation, 2005).

Bolger, Lt. General Daniel P. "MacArthur Unleashes 1st Calvary on Manila." Army Magazine 65, no. 2 (February 2015): 59-61.

Bundgaard, Leslie R. "Philippine Local Government." Journal of Politics 19, no. 2: 262-283.

Carol Morris Petillo, Douglas MacArthur: The Philippine Years, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981).

Chen, C. Peter. "Invasion of the Philippine Islands." World War II Database. (Copyright © 2004-2016 Lava Development, LLC) http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=46

Connor, Joseph. "Imaginary Invasion." World War II Journal 30, no. 4 (Nov/Dec 2015): 62-67.

Danquah, Francis K. "Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in World War II from Japan's English Language Press." Agricultural History 79, no. 1 (2005): 74-96.

Donald Knox, Death March: The Survivors of Bataan, (New York: Harcourt, 1981).

Frederick H. Stevens. "Santo Tomas Internment Camp: 1942-1945." Limited private edition (1946).

History.com Vault, Japanese-American Relocation, A&E Networks, 2009. Accessed on November 12, 2016, http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese- american-relocation

Juergen R. Goldhagen, Manila Memories: Four Boys Remember Their Lives Before, During and After the Japanese Occupation, (London: Old Guard Press, 2008).

Marc Favreau, A People's History of World War II, (New York: The New Press, 2011).

Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. "open city," accessed November 14, 2016, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/open%20city

Michael C.C. Adams, The Best War Ever: America and World War II, (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1994).

Mudt, Joel. "The Streets Run Red in Manila," WorldPress, accessed on November 9, 2016. https://todayshistorylesson.wordpress.com/tag/admiral-sanji-iwabuchi/

Naidu, G.V.C. "Repression and Resistance." Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 3 (January 1985): 101-103.

National WWII Museum of New Orleans, By the Numbers: Worldwide Deaths, accessed on November 14, 2016. http://www.nationalww2museum.org/learn/education/for-students/ww2- history/ww2-by-the-numbers/world-wide-deaths.html

Orendain, Joan. "February 1945: The Rape of Manila." Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 16, 2014, http://globalnation.inquirer.net/99054/february-1945-the- rape-of-manila

Park, Madison. "How the Philippines Saved 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust," CNN, February 3, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/02/world/asia/philippines-jews- wwii/

Petillo, Carol M. "Douglas MacArthur and Manuel Quezon: A Note on an Imperial Bond." Pacific Historical Review 48, no. 1 February 1979): 107-117.

Pew Research Center's, "Five Facts About Catholicism in the Philippines:" http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/01/09/5-facts-about-catholicism-in- the-philippines/

Robert H. Jackson, That Man: An Insider's Portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt, (New York: Oxford Press, 2003).

Roland H. Worth, No Choice But War: The United States Embargo Against Japan and the Eruption of War in the Pacific, (New York: McFarland, 1995).

SE Asia & Pacific: Philippines, Imports. Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, Executive Office of the President (Accessed 11/12/16). https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/southeast- asia-pacific/philippines

Smith, Steven Trent. "Moving Target." World War II Journal 26, no. 6 (March/April 2012): 36-43.

Studs Terkel, The Good War: An Oral History of World War II, (New York: Pantheon, 1984).

Thiele, Rose Marie. (retired, United Nations Secretary). Interview by author. Summerlin, NV, November 2, 2016.

Thomas W. Zeiler, Annihilation: A Global Military History of World War II, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Toda, Roberto P. Diary. 1937-1992. Unpublished memoirs. Personal collection of M. Martha Helak.

The World Factbook 2013-14. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2013. East and Southeast Asia: Philippines. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world- factbook/geos/rp.html

United Nations Philippines, http://www.un.org.ph/

Ward, James M. "Legitimate Collaboration: The Administration of Santo Tomas Internment Camp and Its Histories, 1942-2003." Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 2 (May 2008): 159-201.

Weber, Mark. "The Danger of Historical Lies: President Clinton's Distortion of History," The Journal of Historical Review 16, no. 3 (1997). https://archive.org/stream/TheJournalOfHistoricalReviewVolume16Number3/T heJournalOfHistoricalReviewVolume16-number-3-1997_djvu.txt

Wheatcroft, Geoffrey."The Myth of the Good War." The Guardian, (December 2014). https://www.theguardian.com/news/2014/dec/09/-sp-myth-of-the-good-war

Willoughby, Major General Charles A. in Manila (with Antonio Perez de Olaguer, Terror in Manila: February 1945, Philippines: 159-166).

Yu-Jose, Lydia N. "World War II and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines." Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (1996): 64-81.

Endnotes

- The National WWII Museum of New Orleans, By the Numbers: Worldwide Deaths, accessed on November 14, 2016. http://www.nationalww2museum.org/learn/education/for-students/ww2-history/ww2-by-the-numbers/world-wide-deaths.html. Civilian deaths totaled 45,000,000. Battle deaths were 15,000,000. "World-wide casualty estimates vary widely in several sources. The number of civilian deaths in China alone might well be more than 50,000,000."

- Donald Knox, Death March: The Survivors of Bataan, (New York: Harcourt, 1981).

- Bolger, Lt. General Daniel P. "MacArthur Unleashes 1st Calvary on Manila." Army Magazine 65, no. 2 (February 2015): 59-61. Some civilians died from friendly-fire shrapnel, but these casualties were in the minority.

- Thomas W. Zeiler, Annihilation: A Global Military History of WWII, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Douglas MacArthur served as Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government of the Philippines prior to the outbreak of the war.

- Marc Favreau, A People's History of WWII, (New York: The New Press, 2011), Preface x.

- Robert H. Jackson, That Man: An Insider's Portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt, (New York: Oxford Press, 2003). This manuscript was unearthed only recently. It was written shortly before Jackson's death in 1954.

- Juergen R. Goldhagen, Manila Memories: Four Boys Remember Their Lives Before, During and After the Japanese Occupation, (London: Old Guard Press, 2008), 9; and, Antonio Perez de Olaguer, Terror in Manila: February 1945, (Philippines: Memorare Manila Foundation, 2005),93. The narrative of journalist Antonio Perez de Olaguer is another illustration of this tendency; de Olaguer's book expounds upon the sack of Manila in February 1945 from the perspective of the local Filipinos. This work was originally published in 1947 in Spanish, and underwent a translation, revival, and re-publication in 2005, a testament to the emergence in popularity of the common man perspective.

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey." The Myth of the Good War." The Guardian, (December 2014): https://www.theguardian.com/news/2014/dec/09/-sp-myth-of-the-good-war

- Zeiler, Annihilation, 5.

- Studs Terkel, The Good War: An Oral History of WWII, (New York: Pantheon, 1984), Preface vi.

- Weber, Mark. "The Danger of Historical Lies: President Clinton's Distortion of History," The Journal of Historical Review 16, no. 3 (1997). https://archive.org/stream/TheJournalOfHistoricalReviewVolume16Number3/TheJournalOfHistoricalReviewVolume16-number-3-1997_djvu.txt.

In Dwight Eisenhower's declaration of June 6, 1944, issued in connection with the D-Day invasion, Eisenhower called the fight against Nazi Germany, "The Great Crusade." President Bill Clinton boasted that America, "Saved the world from tyranny," during his second inaugural address on January 20, 1997.

- Zeiler, Annihilation, 5.

- Chen, C. Peter. "Invasion of the Philippine Islands."WWII Database. (Copyright © 2004-2016 Lava Development, LLC) Accessed on November 14, 2016.http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=46

- The World Factbook 2013-14. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2013. East and Southeast Asia: Philippines, 1. Accessed on November 14, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html

- Bundgaard, Leslie R. "Philippine Local Government." Journal of Politics 19, no. 2: 262.

- Naidu, G.V.C. "Repression and Resistance." Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 3 (January 1985): 101-103. America also led the Filipinos to believe that "they would leave as soon as the house is set in order."

- Yu-Jose, Lydia N. "WWII and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines."Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (1996): 64-81. American self-interest was evident in shaping the Philippine economy to be "dependent on the United States, the free trade between the two countries being the most controversial." In 1939, Paul McNutt (American High Commissioner), openly voiced opposition to the previously agreed upon plan of Philippine independence, advocated for "dominion" status instead, and that same year, Philippine independence was "postponed for 25 years" (68). While Japan granted the Philippines independence on October 1942 (during its occupation), this independence too was a charade--it was independence in name only (68).

- Yu-Jose. "WWII and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines," 75-76. The Public Land Act forbade ownership of public lands by non-Americans and non-Filipinos. A corporation could only purchase or lease land if 61% of its stock was under American or Filipino ownership.

- Yu-Jose."WWII and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines," 69.

- Yu-Jose."WWII and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines," 75. The embargo had depleted Japan's inventory of oil, so even before the outbreak of the war, Japan had less than two years' inventory remaining.

- Danquah, Francis K. "Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII from Japan's English Language Press." Agricultural History 79, no. 1 (2005): 74-96; and, Roland H. Worth, No Choice But War: The United States Embargo Against Japan and the Eruption of War in the Pacific, (New York: McFarland, 1995).

- The World Factbook 2013-14. Central Intelligence Agency, 1. Accessed on November 14, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html

- The World Factbook 2013-14. Central Intelligence Agency, 1. Accessed on November 14, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html

- The World Factbook 2013-14. Central Intelligence Agency, 1. Accessed on November 14, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html

- Connor."Imaginary Invasion." 62-67. Among these naval bases and airstrips were Clark field, located 50 miles from the capital city of Manila, and Cavite Naval Base, the U.S. Asiatic Fleet's home port.

- Petillo."Douglas MacArthur and Manuel Quezon." 111.

- Yu-Jose."WWII and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines." 78. Japanese men, women, and children who had been interned in Davao City were released on December 20, 1941, following the arrival of the Japanese Army.

- Southeastern Mindanao is located approximately 1,500 miles from the capital city of Manila.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. "open city." Accessed November 14, 2016, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/open%20city: "A city that is not occupied or defended by military forces and that is not allowed to be bombed under international law."

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 36. According to Goldhagen, although Manila was declared an open city, many lived in fear of what the Japanese might do, particularly in light of the Rape of Nanking, which had been broadcast in newspapers and newsreels.

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories,39. The events of December 27, 1941 (the day after the open city declaration), were an exception; Japanese forces violated international law by bombing warehouses along the Pasig River, which resulted in heavy casualties within the Walled City of Intramuros. By the same token, two days later on December 29th, the U.S. infringed upon its own open city declaration and dynamited the Pandacan oil tank fields to prevent the Japanese from accessing the fuel stored there.

- From Oral interview with Author: Thiele, Rose Marie, November 2, 2016. "We did stop school for a while only. But then I remember going back to school during the Japanese occupation at the same school, at Saint Scholastica."

- Smith, Steven Trent. "Moving Target."WWII Journal 26, no. 6 (March/April 2012): 36. Americans were sent to huge prison camps at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila. Santo Tomas was a Spanish, Catholic educational institution founded in 1611.

- Ward, James M. "Legitimate Collaboration: The Administration of Santo Tomas Internment Camp and Its Histories, 1942-2003." Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 2 (May 2008): 159. The camp at the University of Santo Tomas was the largest internment camp in the Philippines. Americans and other Allied nationals would be interned there for 3 years. There were approximately 8,000 American citizens residing in the Philippines, and many were held hostage by the Japanese. Another internment camp was located in Los Banos.

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 62. Narrative of Roderick Hall, "As the war progressed, he [dad] would only get a few half day passes. All leaves finally ended."

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 9 & 43. Swiss citizens were considered neutrals and were permitted to move freely within the occupied territory. Foreign nationals included but were not limited to Chinese, Japanese, Swiss, South Americans, Germans, Italians, and Spaniards. "Swiss, Germans, and Italians were considered by the Japanese to be neutrals, or allies."

- Frederick H. Stevens. "Santo Tomas Internment Camp: 1942-1945." Limited private edition (1946); and, de Olaguer, Terror in Manila,93. "Deaths averaged 5 or 6 per month in early 1944, up to 13 in October 1944 through January 1945, and 37 during the period of February 1-12, 1945."

- "How the Philippines Saved 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust," CNN, February 3, 2015. Accessed on November 14, 2016. http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/02/world/asia/philippines-jews-wwii/

From: Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 59. "Fortunately for us, the Japanese were not anti-Semitic. There was to be no ill-treatment of the Jews...they did classify Jews at a slightly lower category than non-Jewish Germans. At that time, none of us knew what was happening to the Jews in Germany."

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 62.

- Ward. "Legitimate Collaboration." 186.

- Zeiler, Annihilation, 2. For the purpose of this paper, POWs are defined as captured Allied military personnel or soldiers of the Philippine Army who were engaged in active warfare in the Philippines at some point during WWII.

- Danquah."Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII." 88.

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 57. As was the case of Mr. Goldsmith, a German Jew who was caught with a home safe containing IOUs from American POWs. Goldsmith was taken to Fort Santiago and tortured. He was eventually released, but died of his injuries soon afterwards.

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 57. "There was always an element of fear of the Japanese." The biggest problem being the language barrier. Filipinos did not know how to speak Japanese, and few Japanese spoke English.

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 49. From Goldhagen, "I asked my mother why she had me tutored rather than send me to a big school like De La Salle, which was run by Catholic Christian brothers. She told me that if I had gone there, I would have had to take Japanese and they did not want me to do that." Japanese language lessons were mandatory during the occupation.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 11. "American or foreign films were not as widely available at that time so that Filipino Theatre Industry was thriving."

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 55.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 11. "The elders would frequent the Jai Alai and the Metropolitan Theatre while the kids would enjoy themselves at home."

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 49.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 11. "Not all Japanese were cruel. There was a Japanese sentry during the Bataan Death March who allowed his prisoner to escape all because of a rosary." Stories of kindnesses included this firsthand account of a Japanese athlete, "a representative of Japan to the Asian Games which where were held in Manila a few years before the war. Because of limited hotel space, some athletes were housed in different venues. De La Salle College provided part of the school for some athletes accommodations, and this particular soldier stayed there. Every morning, when he would walk around the school, the Japanese athlete noticed the students carrying their rosaries [a DLS tradition]. During the Death March, when the sentry saw the prisoner with the rosary, the sentry asked if the prisoner had gone to De La Salle, and when the prisoner said yes, the Japanese sentry set him free."

From: Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 47. "What we didn't realize at the time was that the Japanese love children...I was feeding one of their horses some sugar and it tried to take a bite out of my light blonde hair, probably thinking it was straw. A Japanese soldier saw what was about to happen, and stepped in and stopped the horse."

- Naidu. "Repression and Resistance." 101. About 8 in 10 Filipinos today are Catholic according to the Pew Research Center's, "Five Facts About Catholicism in the Philippines:" Accessed on November 14, 2016. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/01/09/5-facts-about-catholicism-in-the-philippines/

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 65.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 4. Some mestizos were listening to a short wave radio when they were raided by a band of Japanese militia. The entire family was brought to Fort Santiago and "were never heard of again."

Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 67. The Japanese required that all radios must have the "short wave coils removed." The risk of non-compliance was a one-way trip to "Fort Santiago for torture, or towards the end" execution.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 7.

- Danquah."Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII."76, 92. Abaca (Manila hemp) was invaluable to the Filipinos, because it served as a raw material for fishing nets, rope, paper, socks, and water hoses. Fishing in particular was a major industry. During the war, abaca was used by the Japanese in the production of military gunnysacks.

- Danquah."Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII." 75.

- Danquah."Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII." 75. Prior to the war, approximately "90 percent of the islands' sugar exports went to the United States."

- Danquah."Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII." 2.

- Danquah."Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII."4.

- Zeiler, Annihilation, 1.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 4. Corroborated in oral Interview with Author: Thiele, Rose Marie, November 2, 2016. Corroborated in an Interview with American Major General Charles A. Willoughby, in Manila (de Olaguer, Terror in Manila: 159-166).

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 4.

- Oral Interview in Manila with: de Olaguer, Terror in Manila, 166. Major General Charles Willoughby, U.S. Army, served as Douglas MacArthur's Chief of Intelligence, Section G-2, during most of WWII.

- The Battle of Manila and the sacking of the city began on February 3, 1945 and ended on March 3, 1945.

- Goldhagen, Manila Memories, 116.

- de Olaguer, Terror in Manila, 29, 63-64, 101, 135. Corroborated in Oral Interview with Author: Thiele, Rose Marie, November 2, 2016.

- Andrew Gonzales and Alejandro T. Reyes, These Hallowed Halls, Unknown Binding, 1982.

- de Olaguer, Terror in Manila, 133. Some sources put the number at fifteen Christian Brothers killed at DLS.

- de Olaguer, Terror in Manila,131-137.

- de Olaguer, Terror in Manila,106-109.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 4.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary, 14.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary,2.

- Zeiler, Annihilation, 5.

- Zeiler, Annihilation, 5.

- Bolger. "MacArthur Unleashes 1st Calvary on Manila." 61.

- Bolger. "MacArthur Unleashes 1st Calvary on Manila." 61.

- Bolger. "MacArthur Unleashes 1st Calvary on Manila." 61.

- Bolger "MacArthur Unleashes 1st Calvary on Manila." 61. Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, Imperial Japanese Navy.

- Naidu. "Repression and Resistance." 101-103. America also led the Filipinos to believe that "they would leave as soon as the house is set in order."

- The World Factbook 2013-14. Central Intelligence Agency, 1. Accessed on November 16, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html

- Danquah. "Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in WWII," 86.

- Toda, Roberto P. Diary. "That night of December 8, 1941 when the bombs first started to drop. Soon after Pearl Harbor the Japanese started landing in Lingayen, north of Manila."

Oral Interview with Author: Thiele, Rose Marie, retired United Nations Secretary, November 2, 2016. That day "was the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. The Philippines is a very Catholic country, and so I remember it well."

- Chen. "Invasion of the Philippine Islands." 1.

- Chen. "Invasion of the Philippine Islands."1; and, Petillo."Douglas MacArthur and Manuel Quezon." 113. On February 8, 1942, a dispatch was issued from Fort Mills on Corregidor in which President Quezon suggested surrender and neutralization of the islands; MacArthur seemed to acquiesce, arguing that "the temper of the Filipinos is one of almost violent resentment against the United States."--MacArthur to Marshall, February 8, 1942, No. 2275, NNMM, NA. FDR's response was "emphatically deny[ing] the possibility of this government's agreement." Although Roosevelt granted MacArthur "permission to surrender Filipino troops, "Americans were not permitted to surrender."

- United Nations Philippines. Accessed on November 14, 2016. http://www.un.org.ph/

Save Citation » (Works with EndNote, ProCite, & Reference Manager)

APA 6th

Helak, M. M. (2017). "World War II in the United States Colony of the Philippines: Beyond the Bataan Death March and Douglas MacArthur." Inquiries Journal, 9(03). Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1552

MLA

Helak, Martha M. "World War II in the United States Colony of the Philippines: Beyond the Bataan Death March and Douglas MacArthur." Inquiries Journal 9.03 (2017). <http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1552>

Chicago 16th

Helak, Martha M. 2017. World War II in the United States Colony of the Philippines: Beyond the Bataan Death March and Douglas MacArthur. Inquiries Journal 9 (03), http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1552

Harvard

HELAK, M. M. 2017. World War II in the United States Colony of the Philippines: Beyond the Bataan Death March and Douglas MacArthur. Inquiries Journal [Online], 9. Available: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1552

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Centuries of subjugation under Spanish and American colonial rule have embedded an idealistic view of white beauty in the minds of Filipinos. It continues to be deeply rooted in Philippine culture due to the constant exposure of Filipina bodies to the advertisements of the massive skin lightening industry. Papaya soap... MORE»

The decades to come witnessed Japan grow at an unprecedented rate, with its economy reaching heights that were unseen in Asia. But this massive growth[1] also came at the cost of Japanese society’s underclasses—the women, the outcastes, the landless laborers, the prostitutes and the peasants. In particular, the hugely... MORE»

Human trafficking is a global issue that is only recently being recognized with global action. The United Nations' Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (UNTIP), the... MORE»

While the enslavement of humans has been occurring even before the dawn of written history, today's form of slavery occurs on an unprecedented scale in both scope and reach. This work attempts to understand the most vulnerable... MORE»

Latest in History

2022, Vol. 14 No. 02

India was ruled by the Timurid-Mughal dynasty from 1526 to 1857. This period is mainly recognised for its art and architecture. The Timurid-Mughals also promoted knowledge and scholarship. Two of the Mughal emperors, Babur and Jahangir, wrote their... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 02

The causes of the First World War remains a historiographical topic of contention more than 100 years on from the start of the conflict. With the passing of the centenary in 2014, a new wave of publications has expanded the scope and depth of historians... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 11

The Sino-Vietnamese War remains one of the most peculiar military engagements during the Cold War. Conventional wisdom would hold that it was a proxy war in the vein of the United States’ war in Vietnam or the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 11

While the Cold War is popularly regarded as a war of ideological conflict, to consider it solely as such does the long-winded tension a great disservice. In actuality, the Cold War manifested itself in numerous areas of life, including the various... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 11

This article analyzes the role of musical works in the United States during World War II. It chronologically examines how the social and therapeutic functions of music evolved due to the developments of the war. This article uses the lyrics of wartime... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 10

Early medieval Irish society operated on an elaborate power structure formalized by law, practiced through social interaction, and maintained by tacit exploitation of the lower orders. This paper investigates the materialization of class hierarchies... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 05

Some scholars of American history suggest the institution of slavery was dying out on the eve of the Civil War, implying the Civil War was fought over more generic, philosophical states' rights principles rather than slavery itself. Economic evidence... Read Article »

|