From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 9 NO. 2Creating the Cult of Xi Jinping: The Chinese Dream as a Leader Symbol

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

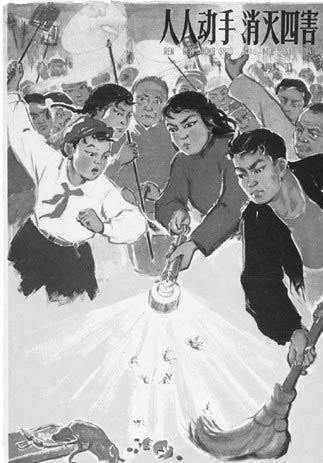

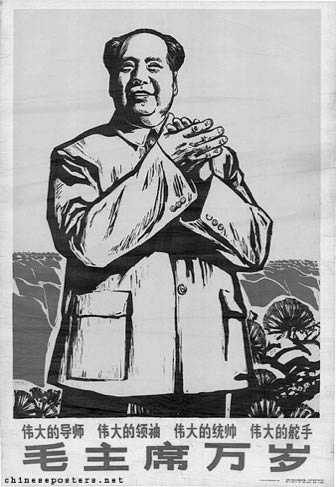

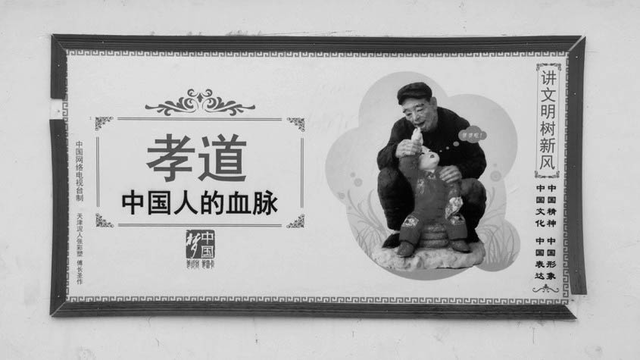

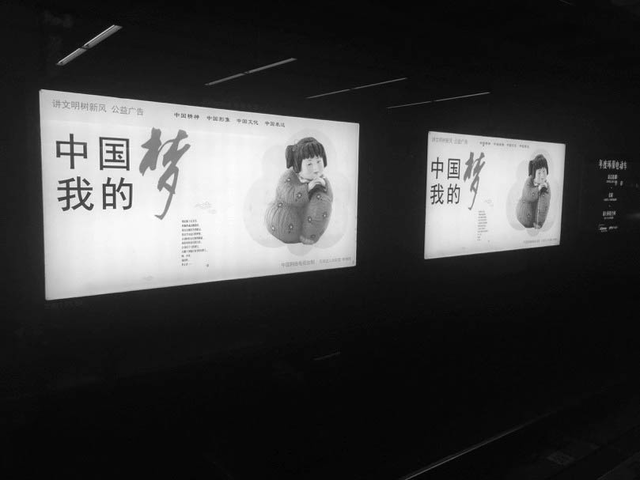

AbstractSince the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party has used publicly displayed propaganda art as a means of maintaining power. During the early years of the PRC, propaganda posters played a large role in establishing a cult of personality around Mao Zedong. Today's propaganda art seeks primarily to garner popular support for President Xi Jinping's "China Dream" campaign. The China Dream, popularized by Xi in 2012, is a nebulous concept that shares many of the materialistic components of the "American Dream," but simultaneously—and more importantly—emphasizes the Chinese nation's rejuvenation to a position of wealth and power. China Dream art deviates significantly from Mao era posters and ideology by heavily incorporating ancient Confucian concepts and images. The art focuses not on communist values, but on moralistic ones drawn from the teachings of Confucius that emphasize hierarchy and filial piety. This paper argues that China Dream art is being used not only to create a new source of legitimacy for the Communist Party, but also to establish a cult of personality around President Xi Jinping. As a result, China is transforming into a leader state where the relationship between Xi Jinping and the people is becoming a relationship between ruler and ruled. Propaganda art has long been an important means of political communication and expression in China. Since the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has used publicly displayed propaganda art as a means of retaining its power and ideological legitimacy. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), propaganda art–mainly posters (haibao 海报)–played a key role in establishing a cult of personality around Mao Zedong. The legacy of propaganda poster art is still present in contemporary China. Today's propaganda art seeks primarily to garner support for President Xi Jinping's "China Dream" (zhongguo meng 中国梦) campaign. The China Dream, popularized by Xi during a speech in 2012, is a nebulous concept that shares many of the materialistic components of the "American Dream," but simultaneously— and more importantly—emphasizes China's rejuvenation as a nation with wealth and power (fuqiang 富强). Since the fall of the Qing Empire in 1911, China's leaders have dreamed of restoring the Chinese nation to its former glory. The China Dream is Xi Jinping's contribution towards this goal. After Xi first proposed the concept of the China Dream in a speech in 2012, China Dream propaganda art began appearing in cities across China. In some of the largest cities, especially Beijing, the art effectively dominates many public spaces. This paper uncovers the role that China Dream propaganda art plays in creating a cult of personality around President Xi Jinping. To do this, it first uses contemporary social and political evidence to show that a cult of personality is forming around Xi. It then interprets the proliferation of China Dream propaganda art both within the historical context of Mao era propaganda art and within the context of the contemporary Chinese political and social climate. It demonstrates that the propaganda art of the Mao era and today's China Dream art share two key aims: propagating Party ideology as a means of retaining legitimacy and creating a cult of personality around the top national leader. However, the implementation of the two exhibits key differences. First, China Dream propaganda art deviates significantly from that of the Mao era because it relies not on the communist values of that period, but on moralistic ones drawn from Confucian teachings emphasizing hierarchy and filial piety. This is because as China continues to liberalize its economy, and economic growth slows, it needs to find new sources of ideological legitimacy. Second, unlike the art of the Mao era, which depicted the figure of Mao on a vast number of posters, China Dream art typically contains no direct references or depictions of Xi Jinping. Because Xi's image is not typically directly invoked in China Dream art, demonstrating that the art helps to create Xi's personality cult requires a deeper level of analysis. Grounding its analysis in the theory of "leader symbols," this paper argues that China Dream art is a powerful and ambiguous leader symbol that continuously constructs and shapes Xi's personality cult. This paper is not the first to claim that Xi Jinping's immense power is tantamount to a cult of personality.2 However, its argument is unique in its assessment of the centrality that China Dream propaganda art plays in constructing Xi's personality cult. Lastly, this paper argues that Xi Jinping's massive accumulation of political power and the building up of his personality cult are creating a leader state in which the fundamental relationship between the Chinese state and its citizens is changing. The results of this process will have significant implications for both China and the world.This research employs multiple sources and methodologies. Most importantly, it draws on primary photographic evidence of China Dream propaganda art that I collected during field research in China from May to August 2015. While in China, I traveled to five cities: Shenzhen, Shanghai, Nanjing, Beijing, and Qufu. These cities were specifically chosen for methodological purposes to account for variation in their historical, cultural, political, and economic characteristics. Shenzhen, located just across the mainland's border with Hong Kong, was China's first Special Economic Zone and one of its most successful ones. Known popularly as "China's Silicon Valley," Shenzhen's population has grown rapidly to about 11 million as migrants move to work in its massive manufacturing and technology industries.3 Shanghai was included because it is one of China's most populous and economically developed cities. It is one of China's most globalized cities, primarily due to it business activity and human capital.4 This puts it in stark contrast with China's less developed, more rural cities. Nanjing was chosen because it has a medium-sized population of around 7 million, and also has a notable history as one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China. Beijing was chosen for obvious reasons: it is China's second most populous city after Shanghai, and it is the capital city of China. Beijing is the seat of power from which the CCP governs. As such, I expected to find the greatest amount of China Dream propaganda here; indeed, the presence of China Dream posters in Beijing far exceeded that of any other city. Last, Qufu was selected because, in addition to being a very rural city with a small population, it is famous for being the hometown of Confucius. Given China Dream propaganda's emphasis on Confucianism, this offered the potential for interesting variance in its propaganda art. In addition to primary sources of China Dream art, this paper also relies on the informal conversations that I had with Chinese citizens. These conversations were not formal interviews and were not designed to account for variation among different people; they are simply used to provide context. I also reference scholarly and journalistic sources to provide additional evidence of Xi Jinping's growing political and social influence and the development of a personality cult. To ground the paper's theoretical claims, it builds on the theory of "leader symbols," which was developed by Jae-Cheon Lim. While Lim's work focuses on the personality cult of North Korean leaders, it provides a helpful theoretical lens through which to interpret and analyze propaganda art in China. Cult of Personality: Context and TheorySince assuming power in 2012, Xi Jinping has amassed more centralized authority than any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong. He has taken on the traditional roles of "Paramount Leader": President of the PRC, General Secretary of the CCP Central Committee, and Chairman of the Central Military Commission. However, he has also become the head of two newly created bodies: the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms and the National Security Commission. In doing so he has gained direct control over the central state and Party apparatuses. Most notably, immediately after assuming office, Xi announced a major new campaign to root out corruption within the Party. In addition to being widely popular among the Chinese public, these anti-corruption reforms have also been used as a tactic for centralizing power under Xi so that he can pursue greater reforms in the future.5 Does Xi's immense power warrant the label of a personality cult? There is no greater example of a cult of personality than the cult of Mao Zedong, the founder of the People's Republic of China and long-time leader of the Communist Party. In his book Mao Cult: Rhetoric and Rituals in China's Cultural Revolution, Daniel Leese lists some of the characteristics of the Mao cult: "Daily reading of Mao's Little Red Book …, confessions of possible thought crimes in front of Mao's portrait, and even physical performances such as the ‘loyalty dance.'"6 He later describes the role that the media played in creating Mao's cult by referencing the fact that in 1968 at the height of the Cultural Revolution, the phrase "Loyal to Chairman Mao" (zhongyu Mao zhuxi 忠于毛主席) appeared in the state-run newspaper People's Daily almost 1,500 times.7 Are these same phenomena, then, required for a Chinese leader to have a cult of personality? What would a post-Mao cult look like? If these characteristics are necessary, then Xi Jinping cannot be said to have a personality cult. However, even on the basis of these characteristics, he comes surprisingly close. There are no loyalty dances to Xi, but recently the ritual of self-confession (jiantao 检 讨) has returned for the first time since the Mao era. However, the confessions do not take place in front of Xi's image; they take place on public media.8 Today's self-confessions are also different from those of the Mao era because they are now primarily confessions of corruption by Party officials or business leaders, not confessions of deviation from Maoist thought. Despite not being overtly related to Xi, today's self-confessions are a direct reminder of the power that Xi and his anti-corruption campaign exert over individuals. Additionally, while Xi's appearance in the newspaper is still eclipsed by Mao's, in his first 18 months as leader his name was mentioned nearly twice as much as any other leader since Mao.9 This shows that despite not reaching the full extent of Mao's media presence, Xi's media presence is significantly larger than that of any other previous Chinese leader, even Deng Xiaoping. This trend shows no sign of slowing. On December 4, 2015, People's Daily mentioned Xi's name in 11 different front-page headlines. In an article about this phenomenon, Felicia Sonmez of the Wall Street Journal wrote: "State media's unswerving focus on Mr. Xi has set China's leader apart from his recent predecessors and spurred much speculation among China watchers over whether the country is on the path toward another personality cult similar to the one that surrounded Mao Zedong in the 1960s and '70s."10 She then went on to explain why this shift is so important. Since Mao's death, the CCP has gone to great lengths to ensure that another personality cult does not arise within the Party leadership. The Party has typically played down the public presence of leaders; yet the fact that the People's Daily focuses so much attention on Xi shows a marked shift from this pattern.11 There is other evidence that suggests Xi is building up a cult of personality. In September 2015, China held a massive military parade through Tiananmen Square to commemorate the defeat of Japan in World War II. This event is what Lisa Wedeen refers to as a "spectacle": a public symbol through which power is displayed and projected.12 Of course, parades and events such as this have taken place under past leaders; however, Xi used this particularly important event to demonstrate his power. In a speech given at the parade, he announced that the Chinese military would demobilize 300,000 troops. Ironically, in demobilizing troops, Xi demonstrates the firm grasp he has over the military and the extent of his reform capabilities.13 Given the Chinese military's rapid development in recent years, Xi's demonstration of his firm grip over the military is an especially potent utilization of a "spectacle" to show his authority. Taken together, this evidence suggests that a cult of personality is forming around Xi Jinping, but it does not explain how the cult came to exist. The core argument this paper makes is that the China Dream and its propaganda art play a key role in creating this personality cult. But how exactly does propaganda art help to bring about a cult of personality? Looking at other cases of personality cults helps to explain how they come to be. One does not have to look far from China to find a robust, modern cult of personality; North Korea's Kim dynasty provides a prototypical example of what a personality cult and a "leader state" look like. Jae-Cheon Lim argues: "North Korea can be systematically considered a ‘leader state' whose legitimacy is based solely on the leaders' personal legitimacy and is maintained mainly by the indoctrination of people with leader symbols and the enactment of leadership cults in daily life."14 He says that the prevalence of leader symbols and the routine, everyday encounters with leader symbols bring about the indoctrination of people into a cult of personality and the creation of the "leader state."15 Before applying this theory to the China Dream, the issue of the China Dream's ubiquity as a symbol must first be established, because leader symbols must be present in all areas of life, both public and private, to be effective at indoctrinating people into a personality cult. This paper does not argue that China Dream art is as prevalent as leader symbols in North Korea. The extent to which the Kim dynasty has consolidated a personality cult is without match, even in comparison to the Mao cult. Yet China Dream art is still a ubiquitous symbol that incorporates practices of cult rituals. However, this is only true in certain areas. For instance, Beijing's public spaces are heavily covered in China Dream art. At various locations throughout the city, building walls alongside roads are covered with posters, often for a hundred meters or more (see Figure 1). For those who walk these streets every day, it is impossible not to notice them. One potential weakness of this paper's argument is that the presence of these posters is not as prominent in other cities. In the small, rural village of Qufu, for example, I saw very little presence of China Dream posters in comparison to Beijing. But this does not discount my theory for two reasons. First, rural Chinese towns and villages such as Qufu are significantly less important politically than massive cities like Beijing. As stated previously, Beijing is the seat of power of the Party and the government. In the hierarchy of Chinese cities, Beijing is at the very top. Second, Xi Jinping has only been in power for about three years. Thus, the China Dream is a young, developing leader symbol. The Kim dynasty has had decades to create and build its leader symbols. For these reasons, the smaller presence of posters in more rural areas should not discount the overall effect that posters have in shaping Xi's cult. Second, China Dream art has entered into citizens' private lives, giving it more indoctrinating power. For example, in China, giving calendars during the New Year—China's most important holiday—is an old tradition. In January 2015, the most popular New Year calendars depicted Xi and his wife underneath the Chinese characters for "China Dream."16 This is important for two reasons. First, these calendars are typically cherished gifts that people share with each other, and they are brought into the home for decoration. This shows the incorporation of the leader symbol into the private, intimate space of the home. Second, these calendars are particularly important because they directly associate the image of Xi Jinping with the China Dream, which the publicly displayed posters did not. These calendars not only incorporate the leader symbol into the private space of the home, but also into a ritualized custom of sharing gifts during the annual Chinese New Year season. This shows the increasing presence that China Dream art plays as a ubiquitous leader symbol helping to create a personality cult around Xi Jinping. Comparing the Cults of Mao and XiIn applying Lim's theory of leader symbols to Xi Jinping and China, this paper focuses specifically on the use of leader symbols as a means of developing and maintaining Xi's cult. Lim lays out six specific functions of leader symbols: communication, relationship objectification, meaning condensation, integration, legitimacy promotion, and mass mobilization.18 On the basis of Lim's theory, if a symbol is ubiquitously incorporated into everyday life and successfully serves these six important functions, this suggests that such a symbol is in fact a leader symbol being used to create a cult of personality and transform the state into a leader state. As discussed earlier, Mao Zedong built one of the most robust personality cults in history. This section systematically shows how Mao used propaganda art as a successfully functioning leader symbol to create his cult of personality. Then, it shows how Xi Jinping is also successfully doing so in ways that are both similar and different from Mao. Communication FunctionThe first function, communication, is simply the ability to employ a leader symbol— in this case, propaganda art—to persuade the people to serve the aims of the leader.19 Communication was, perhaps, one of the most important functions of the propaganda posters during the Mao years, especially during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. The CCP constantly put out posters promulgating Mao's policy ideas. One example of this is the posters calling for all Chinese people to carry out Mao's Four Pests Campaign, which asked everyone to do all they could to kill rats, flies, mosquitos, and sparrows. The poster shown in Figure 2 shows a Four Pests Campaign poster that says, "人人动手消灭四 害" ("Everybody get to work to destroy the Four Pests").20 Unfortunately, Mao's calls to kill the Four Pests and the corresponding propaganda campaign were highly successful. They resulted in the destabilization of China's ecological system, which, among other factors, contributed to terrible famine and the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese people. Xi's China Dream art certainly serves the communication function in many aspects. A common theme among many of the posters in every city is the emphasis on natural landscapes and environmental conservation. An example of this can be seen in Figure 3, which shows a massive wall poster located on the north side of Picai Hutong, just a few blocks west of the Forbidden City. At this location, there was a long stretch of giant posters stretching for hundreds of feet. This particular poster contains a classical mountain painting scene along with the phrase "人心敬畏天地,才有水美山青," which loosely translates to "until the will of the people reveres heaven and earth, there will not be beautiful waters and green mountains." This directly communicates that in order for the China Dream to be attained, there must be a clean environment. It is a call for people to respect the environment and recognize the importance of environmental protection, even as China develops. Given Xi's announcement during his 2015 state visit to the U.S. that China will implement an aggressive cap and trade program to curb greenhouse gas emissions, this poster is a call for the Chinese people to support and follow these new regulations–a difficult request in a developing economy such as China's. The existence of such China Dream posters suggests that this propaganda art is effectively fulfilling the "communication function" of leader symbols. Relationship Objectification FunctionThe second leader symbol function, relationship objectification, is actually more readily demonstrated by the Xi cult than the Mao cult. During the time of Chairman Mao's leadership, many posters showed images of him and referred to him as the Great Leader. For example, the poster in Figure 4 calls Mao "伟大的导 师 伟大的领袖 伟大的统帅 伟大的舵手," meaning "Great Teacher, Great Leader, Great Commander, Great Helmsman."24 While these epithets convey a relationship of power over the people, they do not convey a sense of closeness and familiarity. President Xi, on the other hand, is commonly referred to as 习大大 (Xi Dada), which literally means "Xi big big," but translates colloquially to Uncle or Father Xi.25 While this has the effect of familiarizing Xi and making him seem like part of one's family, it also has a very significant meaning within Confucian notions of order, which emphasize filial piety. The relationship between father and children is extremely important—it is one of the five fundamental relationships of Confucian social order.26 Thus, when people refer to Xi as Xi Dada, they are equating him with a father figure and making him into China's father figure. This is very important, because as Tatlow says, quoting Daniel K. Gardner: "‘By embracing the nickname ‘Xi Dada,' Xi Jinping is allowing himself to be likened to an imperial ruler who governs by dint of wisdom, compassion and deep familial affection for the people, a ruler who is responsible for doing right by his subjects and guiding them.'"27 China Dream art represents this as well. As previously noted, one thing that makes China Dream propaganda so different from Mao era propaganda is that it draws from Confucian concepts and images, not Communist ones. The poster that best demonstrates this is shown in Figure 5. This poster, located near Longhua Temple in Shanghai, is very common in both Beijing and Shanghai. It depicts a little girl trying to feed her paternal grandfather (爷爷) saying: "爷爷 吃!" or "Grandpa, eat!" The text says, "孝道,中国人的血脉," which translates to "filial piety, the Chinese people's blood lineage." This poster is not only important because it invokes Confucianism, but also because it specifically invokes filial piety. Because Xi is known colloquially as "Father Xi," when China Dream art summons concepts of filial piety, it does two things. First, it incorporates Confucian values into the China Dream. Second, because Xi popularized and operationalized the China Dream, it is indirectly associated with him, and therefore he is also associated with filial piety and notions of Confucian hierarchy. This is an archetypical example of the relationship objectification function of leader symbols. It is the same thing that Kim Jong Il did when carrying out a transition of power from his father to himself. The North Korean leader drew on Confucian notions of loyalty, respect, virtue, benevolence, and filial piety to invoke a hierarchical and ordered Confucian version of the state, which emphasized the role of Kim Jong Il as ruler within the relationship between him and his people.29 In pre-modern Korea, filial piety was a defining attribute of relationships within the family, but as the concept of the "great family" came to exist, it also became a characteristic of the relationship between Kim and the people.30 Just as Kim Jong Il used Confucianism to cement his dominance over the rest of society, Xi Jinping and the CCP are relying on modernized notions of Confucianism to retain their ideological legitimacy. Shufang Wu sums it up well: "The government's overall strategy is to repackage Confucianism, institutionalize it, and integrate it into the current ideology. The aim is to provide further justifications for the CCP's political strategies and policies, make them acceptable to society, legitimate the party's rule, and consolidate its leadership."31 This paper argues that the use of Confucianism is more powerful than any other potential source of ideological legitimacy because it is, at its very core, Chinese. Chairman Mao's legitimizing ideology, known as Mao Zedong Thought, while still highly influential, was a form of communism very similar to Marxist-Leninist thought borrowed from Russia. Communism is not a Chinese creation. Confucianism, however, was the governing ideology in China for hundreds of years and was created and cultivated in China. As a result, Confucianism brings with it a stronger sense of national pride and unity than any other ideology might provide. In short, the China Dream's inclusion of Confucian values, especially filial piety, make it particularly effective in its relationship objectification function, in much the same way as in North Korea. Meaning Condensation FunctionThe third function, meaning condensation, is the ambiguous quality of a leader symbol that allows people to experience and internalize it differently at different moments.32 For example, Lim notes that peoples' reactions to seeing images of Kim Il Sung laughing in the media can bring about emotions of longing or disgust, depending on which side of the Korean War one was. Similarly, posters of Mao Zedong can have the exact same effects, depending on which side one supported during the Chinese Civil War. Any of the many Mao posters, which directly sought to create his personality cult, could be said to be ambiguously positive or negative in this way. However, the China Dream campaign is so ambiguous that it is hard to have a negative reaction to it. That is because there is no strict definition of the China Dream. One particular message, found in posters, online, and even in a television commercial, is perhaps the most famous China Dream message: "中国 梦,我的梦," which means "The China Dream, My Dream." The famous poster bearing this message, which I saw in Shenzhen, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Beijing, can be seen in Figure 6. The particular photo shown in Figure 6 was taken at a station on Line 1 of the Nanjing Subway system. On that particular line, every station I visited had multiple China Dream posters, usually including the "China Dream, My Dream" poster found in Figure 6. Why is this China Dream message the most prolifically displayed? Since the message being sent is that the China Dream is intentionally ambiguous, it is up to people to decide for themselves what their China Dream looks like. This not only enables personal connection with the government's propaganda campaign, it also gives individuals some sense of agency in pursuing their version of the China Dream. In my conversations with Chinese citizens, I heard many different definitions of what the China Dream means for them. In Shenzhen, I talked to a worker at a police training school in his late twenties, who worked under the mother of the family hosting me. He talked openly about the China Dream and said that because he likes to travel, for him, the China Dream means a passport that will let him travel anywhere in the world. The father of my host family, who is a very wealthy CEO of a Chinese company, told me that his China Dream meant being able to come up from poverty to own a large house, and especially to have his own garden. Both he and his wife constantly showed me the vegetables that they were growing in their garden, and they seemed more proud of the garden than their massive house. In a large, crowded city such as Shenzhen, owning a house with the space to grow a garden is a symbol of wealth and privilege. The differences in these two narratives of the China Dream show the extent to which Chinese people interpret it individualistically. This paper argues that the ambiguity of the China Dream as a leader symbol is one of the characteristics that makes it so powerful as a tool for propaganda and especially for creating a cult around Xi. Previous propaganda campaigns in contemporary China, such as Hu Jintao's "Harmonious Society," did not allow for the openness of interpretation that the China Dream does. This ostensible inclusivity and granting of agency allows people of vastly differing backgrounds and views to still support Xi Jinping and his goal of attaining the collective China dream. This gives Xi a chance to shape and use the China Dream to shore up support for himself, and build up his own cult, while still allowing the Chinese people to feel a sense of agency. This reality is expressed by Professor Steve Tsang, director of the Chinese Policy Institute at the University of Nottingham: "The Chinese Dream is not the dream of the people of China freely articulated by them. It is the ‘Chinese Dream' to be articulated on their behalf by Xi and the Communist Party."34 Thus, in appearance the China Dream leaves open all sorts of interpretation, which in turn serves to support Xi and his policies; but in reality, it is Xi and the CCP articulating the dream. In this way, the China Dream remains an ostensibly inclusive leader symbol that is actually shaped solely by Xi. This is one of the things that makes the China Dream such a uniquely powerful leader symbol.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |