Propaganda, Idealism, and Subculture: The Evolution of Che Guevara's Image in Chinese Cultural Memory

By

2021, Vol. 13 No. 02 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

AbstractBeing a worldwide popular icon, the Argentine Marxist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara has been differently re-appropriated by a variety of movements across the globe; but his reception and symbolization in contemporary China has been less discussed by western scholars. This paper examines the image and reception of Che Guevara in Chinese cultural memory from the 1950s to the present, revealing his manifold significations endowed by different social groups in various historical contexts. He evolved from a propagandized model of the socialist revolution and anti-American hero endorsed by the Chinese Communist Party, to a secret spiritual guide for the “sent-down” youth during the Cultural Revolution; from a nostalgic symbol for idealism generated by Guangtian Zhang’s milestone drama Che Guevara, to a subculture of “Qie Guevara” on the internet that voices discontentment with social and economic inequality. The complex evolution of Che Guevara’s image in modern China testifies to his chameleon-like potential to represent different ideals. This discussion shows how his image has been tailored to various local contexts and has become engraved in Chinese cultural memory. Following his legendary life as well as his tragic, almost-sacred death, the Argentine Marxist revolutionary, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, was transformed into a world-wide popular icon that has shaped the cultural memories of many generations. The paper will examine the development of Che Guevara’s image in China, a topic that is less discussed by western scholars and historians. Guevara’s reception in China can be roughly classified into four stages: firstly, during the period from 1959 to 1965, Guevara was endorsed by the Chinese Communist Party as a heroic symbol of the socialist revolution and anti-Americanism. Then, during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Guevara was officially rejected by the Party but was secretly treated as spiritual guidance by the “sent-down” students living harsh agrarian lives. From the eighties to the beginning of the twentieth century, Guevara became a nostalgic symbol for idealism that became scarce in a society turning toward consumerism and entertainment. Lastly, from 2012 to the present day, the emergence of a subculture “Qie Guevara” among the youths exposed hidden issues of social inequality, class tension, and widespread discontentment, expressing a call to redefine happiness and secure the freedom to live one’s desired life. From the Socialist Hero to a "Bourgeois Opportunist"In 1959, when the Cuban Revolution’s victorious news reached to People’s Republic of China on the other side of the Pacific ocean, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) responded with great enthusiasm and quickly initiated a country-wide propaganda campaign that introduced Cuban history and praised the revolution. Che Guevara, a major figure of the revolution and the Minister of Industries, was especially endorsed by the CCP as a political model for socialist revolutionary and a hero who resisted the U.S. imperialism. His speeches and writings began to frequently appear on People's Daily, China's official newspaper directly managed by the Party, the most widely read publication in China during that time. From 1959 to 1965, there were in total 83 pieces of translated articles and remarks by Guevara published on People's Daily, the majority of which shared the theme of anti-U.S. imperialism1. Titles were written in a similar style: "Guevara said that the U.S. imperialism would not make Cuba surrender"2, "Guevara said that there would not be peace as long as imperialism exists,"3 "Guevara said that the U.S. imperialism is the main enemy to people of the world,"4 and so on. The “Guevara said” series perfectly exemplifies the Party’s endorsement of Guevara, who was presented as a well-received anti-American hero with worldwide support. Besides underlining Guevara’s anti-American stance, People’s Daily also published photographs of Guevara’s visit to China in 1960, showing scenes that became key events in Chinese public memories: pictures of him receiving flowers from students, meeting with Mao, visiting rural villages, and spending time at kindergartens with children…5 these captured moments were together woven into his image in the eyes of the Chinese people – a heroic yet humanistic leader.Guevara's reception in China became suddenly reversed, however, as international politics shifted to a new paradigm. Shortly after the 1959-1965 period, the CCP began to distance itself from the socialist Cuba: China’s relationship with the Soviet Union deteriorated, and Cuba chose to ally itself with the Soviet Union by Fidel Castro's decision. In 1965, the two countries' dispute on China's reducing rice supply to Cuba became the last straw; Fidel Castro's speech on Feb. 6, 1966 titled "Castro Statement on Cuban-CPR Relations" accused the Chinese government of "[displaying] absolute contempt toward our country [Cuba]” and imperialism.6 The full-text of Castro’s speech was translated and published on People's Daily, explicitly titled "Fidel Castro’s Anti-China statement,"7 a moment that marked the beginning of cold-war confrontation between China and Cuba.8 It was not by chance, then, that the last time Guevara was mentioned in People's Daily was also in 1965, in a piece of news announcing his resignation and departure from Cuba to foment revolution abroad.9 China's break with the Soviet Union heralded the age of China’s Cultural Revolution, a movement launched by Mao Zedong to re-assert his orthodoxy and authority. During the entire movement from 1965 to 1976, not a single piece of news ever mentioned Guevara – not even on his death in 1967 that shocked the world.10 Yet the Party did not withdraw its attention to this influential revolutionary leader. During the Cultural Revolution, a series of Guevara-related works – including two biographies of Guevara and Guevara's own writings such as Guerilla Warfare and Che Guevara's Diary in Bolivia (1971) – were translated into Chinese and published for "internal reading", a term invented for books that had academic values but were inappropriate for public reading due to the "incorrectness of their thoughts".11 In the Party-dictated editorial notes, Guevara was criticized for not being a true socialist revolutionary: he “did not reply on the masses," practiced “opportunism and adventurism,"12 and was "a bourgeois revolutionary democrat who wrongfully advocated the anti-Marxist 'guerrilla-centered' theory."13 The official evaluation of Che Guevara changed so drastically in the 1970s that it contained self-contradictions that were hard to reconcile. Guevara's double-sided image – ranging from a socialist hero to a "bourgeois opportunist" – was inextricably tailored to the agenda of the Chinese Communist Party. A Spiritual Power for the Sent-Down YouthSurprisingly, while Guevara's heroic image was renounced by the Cultural Revolution’s official language, it was revitalized by the exuberant, idealistic youths sent down to remote countryside for re-education. In 1968, the Chinese Communist Party instituted the "Down to the Countryside Movement", sending over 4 million university and high school students to rural areas to be re-educated through agrarian labor and living peasant lives. The ambitious youths, eager to build a socialist society and excitingly volunteering in this movement, soon found themselves trapped in harsh, repetitive labor work, deprived of spiritual resources. They constituted a generation often referred to as “the lost generation,”14 who worked day after day only to gradually realize the utter nullity of their labor and the unbridgeable distance between their lives and “a true revolution.” Yet many of these disillusioned youths discovered spiritual guidance and comfort in Guevara-related writings published in the form of "internal reading." To overcome the extreme scarcity and strict regulation of these books, the students copied the books by hand at night and circulated the manuscripts secretly. They walked dozens of miles only to borrow a copied Che Guevara's Diary, which was then circulated between several villages, read by countless earnest youths until the copy completely fell apart.15 These youths, hearts filled with revolutionary ideals and adventurous spirits, discovered emotional resonance in Che Guevara's legendary experience and soulful character. "I feel that my soul has flown to the Latin American forests thousands of miles away, immersing in the burning sound of ideals and passions," one sent-down student later remarked on his reading experience.16 Although the Party-dictated editorial notes on the books criticized and depreciated Guevara, the youths rejected the official interpretations; instead, they cherished their individual reading experience during their harsh and lonely days. Guevara's legend became a tremendous spiritual power that supported those disillusioned youths to overcome the bleakness and hardship of their rural lives. They refused absorption into the official voice and instead established individual, spiritual relationship with the "Guevara" imagined and understood by themselves. During the chaotic times of the Cultural Revolution, Guevara’s image was manipulated by the CCP as a political weapon, but in the rural areas of China, individual consciousness and idealism re-gained momentum as "the lost generation" broke away from the authoritative voice and strived to protect their own "Guevara." Che Guevara on Stage: A Nostalgia for Idealism

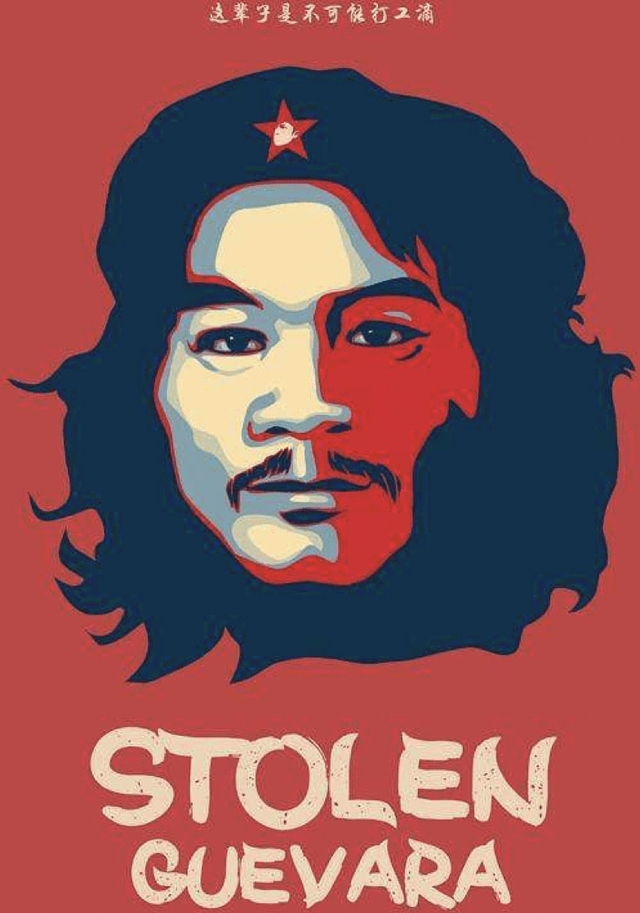

Thirty years after the Cultural Revolution, the name “Che Guevara” re-aroused public attention when the experimental play Che Guevara, directed by musician and playwriter Guangtian Zhang, was performed in Beijing in 2000.18 Shortly after the initial performance, the play became famous country-wide and was elected to 2000’s top ten “Significant Intellectual Events” in China.19 The opening song, whose lyrics are quoted above, was performed by the director Guangtian Zhang himself before the curtain was raised. Born in 1966, Zhang witnessed the idealistic movements in the 1980s in his adolescence, a time when China was recovering itself from the Cultural Revolution’s turmoil and people were dedicating themselves to the pursuit of democracy and freedom. The idealistic period did not last long – it was abruptly crushed by the 1989 Tiananmen Square Incident, which became the most sensitive taboo in Chinese public memories. After the 1989 watershed, older generations became increasingly disillusioned and thwarted in political participations; many shifted their focus to economic prosperity and personal enjoyment. While they refrained from political discussions that steadily became intolerable under the Party’s regulation, young people intended to stay aloof from politics, immersing themselves in the booming entertainment industry. As people’s political enthusiasm faded, the name “Che Guevara” also began to disappear from the public’s view. Zhang’s Che Guevara in 2000, depicting Guevara’s heroic life and undying idealism, revived Che’s image in public memories and reminded the audience of a hopeful past where dreams had not deteriorated into dystopias. The play served not only as a historical reckoning, but also as an ardent call to not obliterate the Guevara-like idealism from the society now turning toward consumerism and entertainment.20 There was no visual representation of Guevara on the stage throughout the play; as Zhang deliberately explained in the script, “Guevara is represented on stage only by an offstage voice.”21 This creates a cinematic timelessness: Guevara existed purely as an ideal, undefined by historical judgements and free from political purposes. Zhang’s Che Guevara was more than an artistic production; it was aimed to be a work of social criticism. Zhang incorporated many Chinese elements into the play, such as the use of Chinese dialects, Peking Opera, and weapons from the 1940s Sino-Japanese war period, creating a spiritual parallel between China and the socialist Cuba that transcends geographical boundaries and cultural differences. While the stories all take place in Latin America, the play makes constant references and allusions to contemporary Chinese society. Exposing issues such as corruption, social inequality, and bureaucracy, Zhang depicted a post-revolutionary society festering with moral decay and inner hollowness. "Why did the broken iron fetters be put on again? Why did the slave become the new king again?" The lyrics of an interlude song reflected a disillusionment with the status quo, that years after the revolution, the promised future of equality and justice was still nowhere to find. The play’s social criticism culminated in the ending scene of a bitter irony, where a woman, who years ago was an aspiring teacher at the school where Guevara was shot to death, became a tour guide at La Higuera and made money by exaggerating her encounter with Guevara to attract tourists. Warning against the danger of consumerism and commercialization, Zhang was ultimately suggesting that the commercialization of Che Guevara is but another form of collective oblivion. Without indulging the audience with redemptive closures nor concealing the cruelty of history, Zhang’s play expressed social criticism, but also took its stubborn and firm stance on idealism. In the performance, after the stage curtain fell amid a sea of red flags, Zhang, together with the entire crew, sang the Internationale together; their singing was also joined by the audience.22 It is hope, represented by the ending song, that have shivered throughout. Just as the opening lyrics suggest: “millennium of dark nights shall today be no more, and perhaps the light will arrive early.” “Qie Guevara”: An Emerging SubcultureBut the light did not come as Zhang wished. Instead, in 2012, the country-wide popularity of Liqi Zhou – known by his nickname "Qie Guevara" – a convict who was arrested for stealing electric bikes, indicates a new stage of Guevara's image that completely broke free from previous expectations. In 2012, a video of Zhou being interviewed in police detention went viral on the internet. When asked by the police why he didn't look for a job to make a living, Zhou, with one hand handcuffed to the bars, smiled and answered uprightly with a comical accent: "working for someone else is impossible. I will never work for someone else in my whole life."23 Zhou's rebellious attitude and his unique appearance – long hairs and a wisp of bread – quickly inspired the public to associate him with the image of Che Guevara (Figure 1). Figure 1: A screenshot from Liqi Zhou’s “Qie Guevara” interview. The subtitles at the bottom are “working for someone else is impossible. I will never work for someone else in my whole life.” He was thus nicknamed "Qie Guevara", as "Qie" means "stealing" in Chinese and has the same pronunciation with "Che". Many young netizens, describing how much they were amused and inspired by Zhou's rebelliousness and calmness, jokingly hailed him as their "spiritual leader."24 The “Qie Guevara” interview video spread like wildfire on social media and garnered millions of views; his quote "never work for someone else in my life" began to appear in various memes and advertisements; his identifiable face was photoshopped onto iconic Che Guevara posters (See Figure 2), and people printed his face and quotes on T-shirts... a lively subculture emerged. Indeed, the decadence of Che Guevara's public image from a revolutionary hero to a bike thief seems more like a farce than a tragedy; yet beneath the abnormal popularity of "Qie Guevara" lies the unseen aspects of social inequality and discontentment. When stating that he would never "working for someone else", the original word Zhou used was dagong, a word that in modern context alludes to factory labor that is characterized by hard work, low wages, harsh environments and instability. Liqi Zhou represents a social group living on the edge of the society: under-educated migrant workers who left their rural homes to seek opportunities in the cities. Figure 2: Liqi Zhou’s face photoshopped onto Che Guevara’s poster. The line at the top reads “impossible to work for someone else in my whole life.” After China's collective economy failed disastrously during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, premier Deng Xiaoping carried out economic reforms in the 1980s that encouraged entrepreneurship, de-collectivized state-owned industries, and promoted a free market economy within the socialist political structure.25 As a result, China experienced a period of rapid economic growth and urbanization, described as "the China miracle," but what went unmentioned were the increasing income inequality, the deepening urban-rural divide, and the living condition of the 200 million migrant workers who built the economy but were exploited by it. In 2010, two years before "Qie Guevara" became a popular icon, fifteen young workers at Foxconn company in Shenzhen committed suicide one by one, a tragic response to the harsh environments, extended work hours, poverty, weak social network, and loneliness that amounted to the precariousness that threatened their daily lives.26 This incident revealed how structural violence and institutional barriers negated the rosy ideal propagandized by the state that working hard leads to success. Many may have noticed this inherent irony within the narrative: the “proletarian working class” became the most exploited and structurally vulnerable group in a society entitled itself "socialism." Nowadays, the red banners prevailing on the streets are still showing the twelve "Core Socialist Values" to every passenger, among which are "prosperity" and "equality."27 The reality is too far from the ideal. In Leslie Chang's Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China, published in 2008 in the U.S., she depicts the everyday lives of female migrant factory workers in China by telling individual stories. She exposed how the young female workers worked countless hours in hazardous conditions, but were still trapped in a downward spiral of poverty and structural inequality, stagnated in their social class.28 Yet such discussions are seldom allowed in China. Keywords such as “low-end population,” which touch upon those migrant workers’ living condition, are strictly censored on Microblog, the biggest cyber platform in China. Journalists and scholars are warned against publicizing opinions that disturb public peace; strike is severely prohibited. The video of "Qie Guevara", in the most bizarre and bantering form, re-attracts the public's attention to the issue of dagong, and to the people who spend their whole lives "working for someone else." Without a serious outlet, people unleashed torrents of emotions in this cult of "Qie Guevara," a comical yet rebellious postmodern anti-hero. One user of the Q&A platform Zhihu, the Chinese version of Quora, wrote in his post: "Leader’s calling has shaken the exploitative nature of capitalism over the proletariat..."29, jokingly adopting the language of class struggle, reminiscent of China's revolutionary past. Being an anti-hero that challenges the sublime image of Guerrillero Heroico, “Qie Guevara” and his subculture are a joke that deconstructs authority. Liqi Zhou's icon becomes a channel through which people enjoy the freedom to express their hidden discontentment and anxiety in a light-hearted way. This subculture refuses absorption into the narrative of exploitative work ethics phrased by the capitalist and entrepreneurial culture. A Foxconn's recruitment slogan reads:

Now the young people respond to it with the "Qie Guevara" quote – “I will never work for someone else in my whole life.” This represents the awakening consciousness of a new generation who rejects the capitalist work ethics that exploit and alienate the individual. With the subculture of “Qie Guevara,” they aspire to define happiness and success by themselves, and in their own language. Che Guevara’s image in modern China varied drastically, testifying to his chameleon-like ability to represent diverse ideals to different groups in varied historical contexts. But what remains essential to Che’s image is its capacity to awaken individual consciousness and rebelliousness, either for the re-educated youths during the Cultural Revolution who developed individual understandings of Guevara that broke free from the authority, or for artists like Guangtian Zhang who aspired to rediscover the Guevara-like idealism and voice his disillusionment with the status quo, or for contemporary workers and youths who rebelled against the exploitative economic system by forming the subculture of the anti-hero “Qie Guevara.” Guevara’s image will continue to change as time marches on, but the ideas of rebelliousness, idealism, and individual consciousness symbolized by Guevara will remain forever as irreplaceable cultural memories of the Chinese society – cherished, celebrated, and passed on by those who strive to see a brighter future. References“Core socialist values,” chinadaily.com.cn, 2017, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-10/12/content_33160115.htm. Castro, Fidel, “Castro Statement on Cuban-CPR Relations,” 1966, Castro Speech DataBase, Latin American Network Information Center, http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/castro/db/1966/19660206.html. Chan, Jenny. "A Suicide Survivor: the life of a Chinese migrant worker at Foxconn." Asia-Pacific Journal,11.31, 2013, 1-22 Cheng, Yinghong, “Che Guevara: Dramatizing China's Divided Intelligentsia at the Turn of the Century,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Vol. 15 No. 2, Fall 2003 Ding, Dong, The Wandering of the Spirit, China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing Corporation, 2000 Feng, Tongtong, “A Musician's Artistic Transcendence and the Loss of Idealism: Guangtian Zhang’s Che Guevara and its Controversial Reception,” Nanking University Journal of Theatre Studies, 2016, issue 2 Guevara, Ernesto, Guerrilla Warfare, translated by Institute of Latin American Studies at Fudan University, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1975 Guo, Xueqing, The Rise and Fall of A Hero, Peking Foreign Language University, 2019 James, Daniel, Che Guevara, translated by Institute of Latin American Studies at Fudan University, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1975 Lu, Xing, Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture, and Communication, University of South Carolina Press, 2004 People’s Daily, Database from Peking University Library. Xu, Ruoqi, Chronicles of My Reading: 1962-1972, Anhui Literature & Art Publishing House, 2016 Ye, Ruolin, “Fresh Out of Prison, Bike Burglar Qie Guevara Shuns Spotlight,” Sixth Tone, 2020, https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1005528/fresh-out-of-prison%2C-bike-burglar-qie-guevara-shuns-spotlight. Young, Jason. China’s Hukou System: Markets, Migrants, and Institutional Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013 Zhang, Guangtian, Che Guevara, reproduced in 2005, https://www.bilibili.com/video/av18381153. Zhang, Guangtian, Jisu Huang and Shen Lin, Che Guevara, translated by Jonathan Noble, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture Resource Center, Ohio State University, https://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/noble/ Zhang, Leslie, Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China, Random House, 2008 Zheng, Ruijun, “The Rule of ‘Internal Reading’ and the Publications of ‘Grey Books’ and ‘Yellow Books’,” Publication Studies, issue 11, 2014. Endnotes1.) Guo, Xueqing, The Rise and Fall of A Hero, Peking Foreign Language University, 2019, 12. 2.) People’s Daily, November 3rd, 1960, section 6. Database from Peking University Library. 3.) People’s Daily, April 18th, 1961, section 6. 4.) People’s Daily, December 28th, 1964, section 3. 5.) Guo, The Rise and Fall of A Hero, 15. 6.) Fidel Castro, “Castro Statement on Cuban-CPR Relations,” 1966, Castro Speech Data Base, Latin American Network Information Center, http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/castro/db/1966/19660206.html. 7.) People’s Daily, February 22nd, 1966, section 3. 8.) Guo, 49. 9.) People’s Daily, October 8th, 1965, section 3. 10.) Guo, 33. 11.) Zheng, Ruijun, “The Rule of ‘Internal Reading’ and the Publications of ‘Grey Books’ and ‘Yellow Books’,” Publication Studies, issue 11, 2014, 96. 12.) Guevara, Ernesto, Guerrilla Warfare, translated by Institute of Latin American Studies at Fudan University, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1975, 2. 13.) James, Daniel, Che Guevara, translated by Institute of Latin American Studies at Fudan University, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1975, 1. 14.) Lu, Xing, Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture, and Communication, University of South Carolina Press, 2004, 195. 15.) Ding, Dong, The Wandering of the Spirit, China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing Corporation, 2000, 37. 16.) Xu, Ruoqi, Chronicles of My Reading: 1962-1972, Anhui Literature & Art Publishing House, 2016, 73. 17.) Zhang, Guangtian, Jisu Huang and Shen Lin, Che Guevara, translated by Jonathan Noble, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture Resource Center, Ohio State University, https://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/noble/. 18.) The recorded version, reproduced in 2005, can be watched at https://www.bilibili.com/video/av18381153/. 19.) Feng, Tongtong, “A Musician's Artistic Transcendence and the Loss of Idealism: Guangtian Zhang’s Che Guevara and its Controversial Reception,” Nanking University Journal of Theatre Studies, 2016, issue 2, 166. 20.) Feng, “A Musician's Artistic Transcendence and the Loss of Idealism,” 169. 21.) Zhang, Che Guevara. 22.) Cheng, Yinghong, “Che Guevara: Dramatizing China's Divided Intelligentsia at the Turn of the Century,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Vol. 15 No. 2, Fall 2003, 5. 23.) The full interview video can be watched at: https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1fx411g74f?from=search&seid=12167295797719116576. 24.) Ye, Ruolin, “Fresh Out of Prison, Bike Burglar Qie Guevara Shuns Spotlight,” Sixth Tone, 2020, https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1005528/fresh-out-of-prison%2C-bike-burglar-qie-guevara-shuns-spotlight. 25.) Young, Jason. China’s Hukou System: Markets, Migrants, and Institutional Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, 49. 26.) Chan, Jenny. "A Suicide Survivor: the life of a Chinese migrant worker at Foxconn." Asia-Pacific Journal, 11.31, 2013, 1-22. 27.) “Core socialist values,” chinadaily.com.cn, 2017, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-10/12/content_33160115.htm. 28.) Zhang, Leslie, Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China, Random House, 2008. 29.) Ye, “Fresh Out of Prison.” 30.) Chan, “A Suicide Survivor.” Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in History |