A Barrier to Prosperity? Analyzing the Impact of Israeli Security Policy on Palestinian Manufacturing Productivity

By

2021, Vol. 13 No. 01 | pg. 1/1

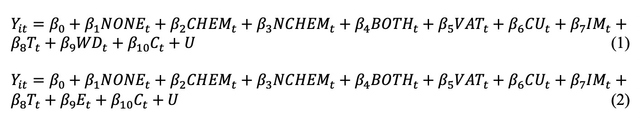

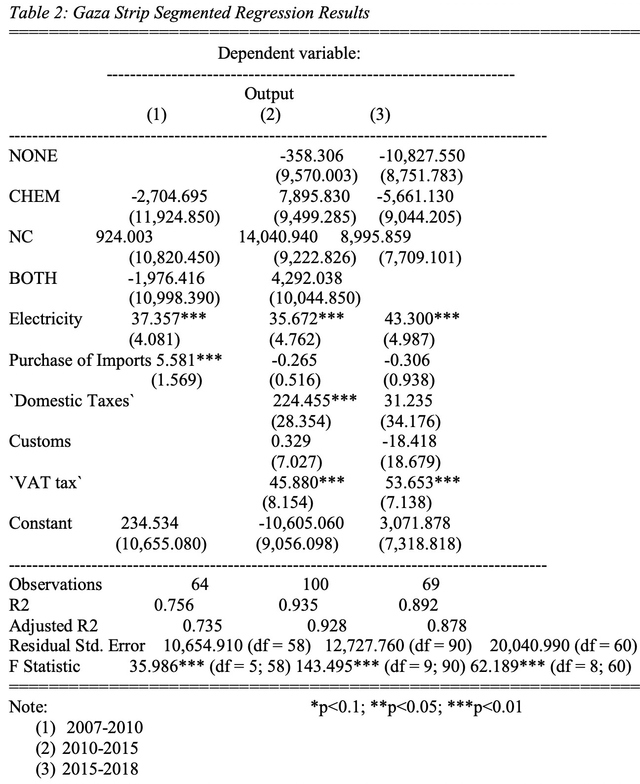

IN THIS ARTICLE

AbstractIsrael has increased the nation’s security presence around the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank. Here, the research project analyzes how transaction costs resulting from Israeli security policy impact the output of manufacturing activities in the Palestinian territories. The study examines transaction costs in the form of import restrictions and items Israel restricts from entering the Palestinian territories in the form of the dual-use goods list. Existing research outlines trade restrictions from Israeli security policy but does not explain how the restrictions impact Palestinian manufacturing productivity. I use a multivariable regression model to look for a correlation between a manufacturing activity’s exposure to Israeli security restrictions, in the form of the controlled dual-use goods list and import restrictions and a decrease in output. The regression breaks down the type of restriction a manufacturing activity could face into no restrictions, restrictions on chemical items, restriction on non-chemical items or restrictions on both chemical and non-chemical items. Furthermore, the project compares costs, procedures, processing times, and documentation associated with Palestinian importation through Israeli vs Jordanian ports. The study found a manufacturing activity's exposure to the dual-use goods list was not a statistically significant predictor of outcome. However, Palestinians face costs due to increased wait times, limitations of port security inspection infrastructure, increased transportation costs, storage fees, and security inspection costs as a result of Israeli security restrictions regardless of the port Palestinians use to import products. These findings demonstrate the need for the Israeli Government to increase the infrastructural capabilities and operating hours of Palestinian border crossings. Today the Palestinian economy relies on the services sector for employment and output. Governmental social services are a staple in both the West Bank and Gazan economies. The expansion of the service sector means the manufacturing sector now plays a smaller role in the overall Palestinian GDP. In 2019, the service sector accounted for 73.4% Palestinian GDP while the agricultural sector decreased from 5.8% to 3.4% from 2005 to 2019 and the manufacturing sector from 25.8% to 22.9% (UNData, n.d.). Governmental social services make up 60% of the Gazan service sector GDP and 32% of West Bank service sector GDP (Al-Falah, 2013). While the Palestinian Authority (PNA) ran a debt-to-GDP ratio of 16% in 2018, decreases in foreign aid to the PNA means the budget deficit will enlarge (International Monetary Fund, 2018). As a result of the agricultural and manufacturing sectors’ decrease in output, a smaller PNA budget poses a large risk to the economic stability of the West Bank. Lastly, Israeli withholding of Palestinian import and value added taxes risks Palestinian job security due to the West Bank labor force’s public-sector employment reliance. As Israel collects Palestinian import taxes, Israel also decides what imports Palestinians can bring into the Palestinian territories. Israel restricts items Palestinians may use in a military fashion via the dual-use restrictions list. The number of items Israel restricts vary based on the security threat of the Palestinian territory. As of April 17th, 2019, Israel restricted the import of 56 categories of items into the West Bank and 61 Gaza Strip specific restricted categories of items (The World Bank, 2019b). Israel first outlined the dual-use restrictions list in the 2007 Defense Export Control Law and the 2008 Defense Export Control Order (Gisha, n.d.). However, in July of 2010 Israel announced a Gaza Strip specific dual-use goods list in addition to the existing list (Gisha, 2016, p. 4). In March and November of 2015, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) added items to the Gaza Strip specific dual-use goods list (see list 3 Appendix B) (Gisha, 2016, p. 4). Because Hamas continues to pose a security threat to Israel, Israel will likely maintain restrictions on Gazan importation of military use items. Because Israel will likely not remove security restrictions on movement and trade in the near future, an analysis of the relationship between the security restrictions and Palestinian economic output may help academics understand the cost of Israel’s security presence on the Palestinian population.This research project investigates how transaction costs from Israeli security policy impact manufacturing output in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Specifically, the research examines how costs resulting from Israeli security policy impact the cost of importing for the Palestinian manufacturing sector. I use a multivariable regression model to look for a correlation between a manufacturing firm’s exposure to Israeli security restrictions, in the form of the controlled dual-use items list and import restrictions, and a decrease in output. Next, the project compares security related costs such as costs due to increased wait times, increased transportation costs, storage fees, and security inspection costs when Palestinian importers import through Israeli vs the Jordanian Ports The project uses dependency theory to show how Israeli security and economic concerns limit the growth potential of the Palestinian economy. Through understanding the causes of Palestinian economic struggles policymakers in Israel, the Palestinian territories, and the United States can decrease poverty and unemployment in the Palestinian territories. Together with improved Palestinian governance, the Palestinian economy will be able to support local Palestinian labor forces and increase economic growth. The paper argues the dual-use goods list does not negatively correlate with manufacturing output in the Palestinian territories while Israeli security restrictions at ports and checkpoints directly increase costs for manufacturing activities. The dual-use goods list is the list of items Israel restricts from entry into the Palestinian territories because Palestinians could use the items for military purposes. The Literature Review covers existing academic scholarship on how the Israel-Palestinian customs union shaped Israeli-Palestinian economic relations and the relationship between Israeli security restrictions and Palestinian trade. The Analysis section runs a regression analyzing how a manufacturing activity’s exposure to the dual-use goods list impacts the activity’s output. The section compares the similarities and differences in security-related costs when a firm imports goods through Israeli vs Jordanian ports. The Discussion examines the contributions of the dependency theory to understanding Israeli-Palestinian trade relations and provides recommendations to decrease security-related costs. Literature ReviewScholars argue the customs union established by the Paris Protocol on economic relations solidified an asymmetrical arrangement benefiting the Israeli economy at the expense of the Palestinian economy. The agreement still defines economic relations between Israel and the Palestinian territories today. Haddad (2016) and Samhouri (2016) argue the Paris Protocol flooded the Palestinian markets with cheap Israeli made products, consequently limiting the competitiveness of the Palestinian manufacturing sector (p. 102; pp. 581-583). Also, the Paris Protocols limited the ability of the PNA to by adjust instruments like fiscal, monetary, trade, and labor policy (Samhouri, 2016, p. 604). Similarly, under the Paris Protocol, Israel retained control over collecting Value-Added Taxes (VAT) and import taxes (Haddad, 2016, p. 102). While the literature covering the Paris Protocols answers how economic integration limits the competitiveness of the Palestinian manufacturing sector; the literature does not answer how hostilities between Israel and the Palestinian territories impact the customs union. To understand the production capability of the Palestinian manufacturing sector, scholars need to examine if Israeli security restrictions on the Palestinian territories limit the ability of Palestinian firms to move goods through Israeli territory under the customs union. Additionally, Scholars are investigating whether limiting Palestinian access to Trade Facilitation Services (TFS) reduces exportation to international markets. Scholars have an interest in Palestinian access to TFS because the West Bank relies on Israel for most TFS. Previous studies evaluated how Israeli security concerns about the Palestinian territories alter Palestinian access to TFS and subsequently reduce Palestinian international market access (Eljafari, 2010, p. 748). Berends (2008) examines the Israeli-Palestinian TFS relationship by analyzing remedies to maximize international market access such as opening the Rafah crossing in Gaza for exports, and improving trade services (Berends, 2008, pp. 152-153). Research analyzing how easily Palestinians are able to access to TFS when importing could reveal if Israeli security policy limits access to inputs for Palestinian manufacturers. Further literature analyzing the ability of Palestinian businesses to access inputs for production may explain changes in the output of the manufacturing sector. Existing academics frame integration between the Israeli and Palestinian economies through the lens of dependency theory. Dependency theory argues the underdevelopment of developing states is due to interactions between dominant and dependent states which reinforce unequal patterns of development. Past research argues the Palestinian economy is dependent on income earned by Palestinian laborers working in Israel (Zilberfarb, 2018, p. 785). The PNA is also dependent upon development focused foreign aid from developed countries and the United Nations to fill the government’s budget (Springer, 2015, p. 4). Lastly, scholars argue the PNA budget is dependent on VAT and import taxes Israel collects and has withheld in the past to punish to the PNA (Daoudi & Khalidi, 2008). However, existing research does not analyze through the lens of dependency theory how Israeli security restrictions on products entering the Palestinian territories limits economic output. Also, the literature does not examine whether the Israeli-Palestinian customs union creates a Palestinian reliance on Israeli trade facilitation. This research adds to existing literature on barriers to Palestinian long-term economic growth by analyzing how transaction costs from Israeli security policy limit Palestinian manufacturing productivity. Existing research outlines trade restrictions from Israeli security policy but does not explain how the restrictions impact Palestinian manufacturing productivity. Furthermore, scholars have examined how the Israeli-Palestinian customs union decreases Palestinian manufacturing productivity but do not incorporate Israeli security restrictions into the research. Other literature has investigated how Palestinian reliance on Israeli TFS reduces Palestinian export access, but the research does not state whether Palestinians face increased security costs when importing using Israeli TFS. The present research analyzes the impact of Israeli security restrictions on Palestinian economic output and the Israeli-Palestinian customs union through the lens of dependency theory. My research will add to existing research by identifying how Israeli security policy impacts the output of Palestinian firms. Israel and Palestinian policymakers can only boost Palestinian economic development after policymakers understand the causes behind the Palestinian economic stagnation. Economic development would improve the quality of life in Palestinian territories while reducing Israeli security concerns. Research DesignDependency theory explains how unequal relationships between the developed and developing states in the world prevent economic growth of developing countries. The theory explains how the lack of growth in developing states comes at the benefit of developed states. Dependency theory labels developed as core states and developing states as periphery states (Shrum, 2001). Dependency theorists argue the impediments to economic growth in periphery states are imposed by developed countries who are pursuing domestic economic interests (Egeonu, 2017, p. 17). Dependency theorist Theontonio Dos Santos outlines the dependence of periphery states as “a situation in which the economy of certain countries (periphery states) is conditioned by the development and expansion of another economy (core states) to which the former is subjected” (Dos Santos, 1970, p. 231). Dependency is useful to understand how the Palestinian reliance on Israel for trade access alters output growth potential in the Palestinian territories. Moreover, the theory is useful to explain whether the Palestinian territories suffer from a reliance on Israel for customs duties, VAT, and import tax collection. I collected data from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) on the output, VAT, domestic taxes, and customs taxes of 30 West Bank and Gazan manufacturing activities (see Appendix A). The Palestinian Trade Center (PALTRADE) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) outlined specific costs associated with Israeli security restrictions. I listed items the Israeli Coordinator of Government Activities (COGAT) added to the Israeli dual use items list between 2007 to 2018. The dual use items list outlines items COGAT restricts Palestinians from importing because of Israeli Government fears Palestinians may use the items for military purposes (Gisha, n.d.). I gathered data from the PCBS’ Economic Surveys Series between 2007 and 2018 on the amount of customs taxes, VAT, and import purchases of a given manufacturing activity to determine whether a manufacturing activity was exposed to Israeli import restrictions. I gathered data on transportation, storage, and inspection costs as a result of Israeli security policy and the infrastructural capabilities of border crossings into the Palestinian territories from PALTRADE and UNCTAD. The time span between 2007 and 2018 is ideal to look for a potential relationship between Israeli security policy and Palestinian manufacturing output because Israel changed items listed on the dual-use items list in 2007, 2010, and 2015. A breakdown of specific costs to Palestinian importers as a result of Israeli security measures allows the project the compare the cost of importing through Israel vs Jordan. To measure the impact of Israeli security restrictions on the productivity of the Palestinian manufacturing sector, I created a spreadsheet consolidating the output of each manufacturing activity and used binary coding to apply the import and controlled dual-use items restrictions to the activities. I used a multivariable regression model to look for a correlation between a manufacturing activity’s exposure to Israeli security restrictions, as in the controlled dual-use items list and import restrictions, and a change in output. I separated dual-use goods list restrictions into no restrictions, restrictions on chemical items, restrictions on non-chemical items or restrictions on chemical and non-chemical items. I coded a manufacturing activity a one in the categories NONE, CHEM, NCHEM, or BOTH based on whether the firm use a dual use goods list item in the production process and a zero in the remaining categories (see Table 1). I used VAT, import purchases, and customs taxes as a proxy for exposure to import restrictions. A multivariable regression is optimal because through statistical significance, a regression describes whether any potential relationship between a manufacturing activity’s exposure to security restrictions and the manufacturing activity’s output is causal or not. The regression controlled for the C, E, WD, and T to account for other variables that might decrease the output of manufacturing firms (see Table 1). The variable WD is only used in regard to the West Bank while E is only used with the Gaza Strip. I used the yearly number of casualties due to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the Israeli NGO, B’Tselem, as a proxy to represent changes in the conflict level between Israel and the Palestine (B’Tselem, n.d.; OCHA, n.d.a). Next, I controlled for differences in wages between Israel and the West Bank for the same manufacturing activity from the Palestinian Labor Force Survey, between 2007 and 2018. From the Economic Surveys Series, I collected data on the domestic taxes each manufacturing activity paid per year not including the VAT or customs duties. I held constant both taxes and monetary compensation to understand the relationship between Israeli security restrictions and the output of the Palestinian manufacturing sector because low domestic taxes and low wages make the two sectors competitive in the region. I controlled for the level of violence in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict per year because escalations in the conflict may decrease productivity and the present research wants to isolate the impact of the import restrictions and the dual-use list on Palestinian manufacturing productivity. I used the multiple regression model (1) for the West Bank and (2) for the Gaza Strip,

To examine the relationship between the controlled dual-use list restrictions, import restrictions, and the output of a manufacturing activity, I used the statistical computing software R Studio to carry out the regression calculations. In the model (see table 1 for descriptions of variable symbols), Y represents the dependent variable, NONE, CHEM, NCHEM, BOTH, VAT, CU, and IM are the independent variables, while T, WD, E, and C are the control variables. b2, b3, and b4 represent the change in output of a manufacturing activity due to the dual-use goods list; b5, b6, and b7 are the change in output as a result of a change in VAT and customs duties paid and imports a firm purchases. As the subscript t labels the variables by year between 2007-2018, the model is optimal because it was able to compare the output of firms exposed to dual-use goods list as the Israeli Government changed the number of items on the list between 2007 and 2015. The model also explains the change in output due to factors other than the dual use goods list and import restrictions such as domestic tax burden, level of conflict, wage differential, and electricity usage.

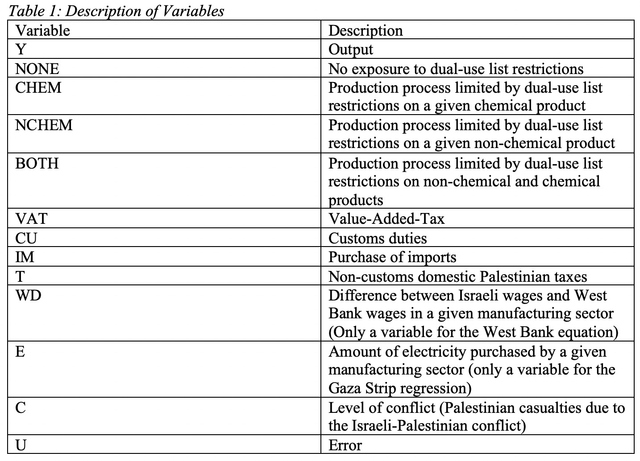

To gain a deeper understanding of the specific security restrictions Palestinian importers face I compared the security restrictions firms encounter when importing products through Israeli vs Jordanian ports. The research project compares the costs of security inspections at ports and checkpoints along with transportation costs and storage costs due to wait times associated with security measures. First, the research breaks down the security and storage cost of importing a smaller 20ft shipping container vs a 40ft shipping container through Israeli ports vs the security-related cost through Jordanian ports. Lastly, the project compares the similarities and differences of security related costs when Palestinians move products through Jordan-West Bank vs Israeli-West Bank crossings. Analyzing the particular costs firms face when importing breaks down how Israeli security policy may harm the output potential of manufacturing activities reliant on imports. Moreover, comparing the security related costs when Palestinians import through Israel vs Jordan can help scholars understand whether the security-related costs alter the decision of where Palestinians want to import goods. AnalysisRegression Findings: 2007-2018The regression examining the impact of a manufacturing activity’s exposure to the dual-use goods list1 on the activity’s output shows Israel’s implementation of the dual-use goods list is not correlated with a decline in Palestinian manufacturing output. The project regresses separately manufacturing activities in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. In the West Bank (column 1 of Table 1), Israeli restrictions on Palestinian access to chemical items or non-chemical items negatively relate to output but are statistically insignificant statistical. In the Gaza Strip (column 2 of Table 1), Israeli restrictions on Gazan access to chemical or non-chemical items positively correlates with output but are of statistically insignificance. As the smaller West Bank dual-use goods list has a negative relationship with output while the larger Gaza Strip dual-use goods list has a positive relationship with output, the regression fails to show a larger list of Israeli import restrictions impacts Palestinian output negatively. The lack of correlation between a Palestinian manufacturing firm’s exposure to the dual-use goods list and output reveals Palestinian manufacturing firms are able to increase production despite Israeli import restrictions.

In the West Bank, a manufacturing activity’s importation of products is a stronger predictor of output than exposure to the dual-use goods list. To represent whether a manufacturing activity relies on imports, the regression uses the amount of imports a firm purchases, along with the amount of VAT and customs duties a manufacturing firm pays. Palestinian companies purchasing imports pay VAT and customs duties when the products arrive at port. VAT is a strong predictor of a manufacturing activity’s output as VAT and output are positively correlated with a 99% confidence level (Table 1). The total customs duties a West Bank manufacturing firm pays is positively correlated with output with a 95% confidence level. The positive correlation between the activity’s purchase of imports and output shows manufacturing activities with higher levels of output in the West Bank are larger importers than activities with smaller output levels. As the data shows a correlation between VAT, customs, purchase of imports, and output, the data reveals the West Bank manufacturing sector is reliant upon imports to increase output. Consequently, Israeli imposed security costs at ports or Palestinian crossings would result in extra costs to a vital step of the manufacturing process. Israel has changed the number of items the Israeli Defense Forces restricts from entering the Gaza Strip multiple times since 2008. Israel has added items to the list when Hamas expands it’s military capabilities and has subtracts items during peace negotiations or at the United Nation’s behest. After Hamas took power in the Gaza Strip in June of 2007, Israel limited imports into Gaza to only humanitarian items including, “ 70 items of foodstuffs, medicines, and grocery items (i.e. detergent, soap)” (Gisha, 2016, p. 1). Israel alleviated the near total blockade in May of 2010; On July 6th, 2010 Israel announced 23 categories of items the IDF would restrict Gazans from importing with the existing dual-use goods list the IDF outlined in 2008 for the Gaza Strip and West Bank (Gisha, 2016, p. 4). In March and November of 2015, Israel added items to the Gaza Strip’s specific dual-use goods list so Israel now restricts 61 categories of items from entering the Gaza Strip (Gisha, 2016, p. 4). The three different versions of the Gazan dual-use goods list means Israel has subjected Gazan manufacturers to three different intensity levels of import restrictions. Consequently, the study can investigate whether the correlation between a Gazan manufacturing activity’s exposure to the dual-use goods list and output vary when the dual-use goods list changes.

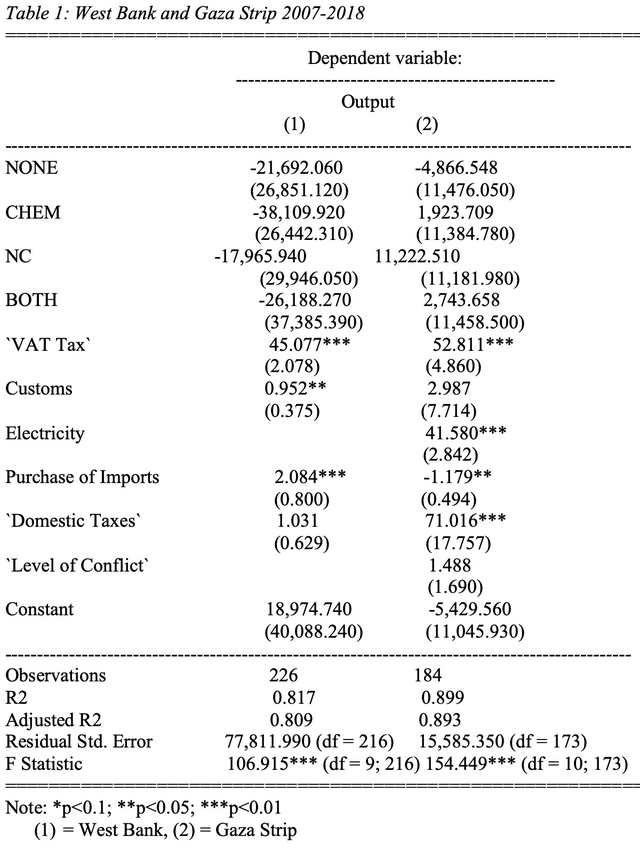

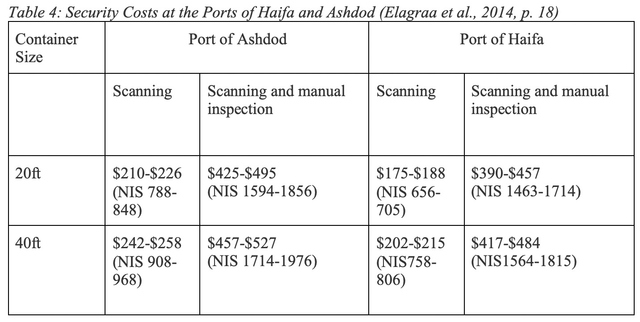

The impact of the dual-use goods list and trade restrictions on Gaza Strip manufacturing activities’ output vary based on the amount of items each dual-use goods list blocks. The first list, from 2007-2010, restricts the most items, the 2015-2018 list restricts fewer items, and the list from 2010-2015 is the least restrictive. Even when the project breaks down the regression based on Israeli changes to the Gaza Strip dual-use goods list, exposure to chemical, non-chemical, both types, or no restrictions, all remain statistically insignificant. During the period of Israel's near total blockade on the Gazan import of goods (2007-2010), and since Israel expanded the dual-use goods list (2015-2018), restrictions to chemical products show a negative relationship with output. When the IDF enforced a smaller list of dual-use goods restrictions (2010-2015), chemical, non-chemical, and both types of restrictions had a positive relationship with output but were statistically insignificant. Therefore, a reduction of the number of items as in 2010 may improve the Gazan economy. As the 2007-2010 and 2015-2018 versions of the list fail to correlate significantly with output, the data further proves the addition of items to the dual-use goods list does not restrict growth of Palestinian manufacturing output. Output of a manufacturing activity in the Gaza Strip correlates more strongly with import purchases and electrical usage than exposure to the dual-use goods list. The study investigates the relationship between Gazan electrical usage and manufacturing output because Israel supplies the Gaza Strip with electricity and power plant fuel. The regression demonstrates manufacturing output in the Gaza Strip increases $41.24 when the amount of electricity a manufacturing activity bought increases $1. Because firms pay the VAT when importing products, the correlation between the total VAT a firm pays and output shows Gazan manufacturing firms with higher output rely on imported products (Table 2). The correlation between a manufacturing firm’s purchase of imports and output was statistically significant during the years of the near total Israeli blockade on imports while not significant between 2010 and 2018. The positive correlation between a manufacturing firm’s electricity usage and output means Israeli restrictions on Gazan electricity allocations limit Gazan manufacturing productivity. Furthermore, the correlation between VAT tax, purchase of imports, and manufacturing output means any additional security costs to Gazan imports would decrease Gazan manufacturing productivity. Dual-Use Goods Restrictions and the Least Productive Manufacturing ActivitiesWhen the research project lists the specific items the dual-use list restricts a firm in the West Bank from obtaining, the list shows West Bank manufacturers with the lowest output more often cite restrictions of non-chemical items as barriers to production. Non-chemical items on the dual-use goods list include items like metals, machinery, vehicles, and tools. In the West Bank, the manufacture of vehicles and trailers, electrical products, machinery, and basic metals are the manufacturing sectors most commonly with the lowest output between 2008 and 2018 (PCBS, 2009, pp. 57-58, 2019, pp. 63-64). The dual-use goods list limits the output of the manufacture of basic metals, machinery, equipment, motor vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers by restricting non-chemical items like metal working machinery, spare parts, and furnaces (Gisha, n.d.). The most commonly restricted items between the activities were sulfuric acid (an input for all four activities except the manufacture of vehicles and trailers) and lathe machines (an input for all four activities except the manufacture of electrical products) (Gisha, n.d.). As the four lowest output manufacturing activities cite restrictions of non-chemical items as impediments to production, the non-chemical restrictions limit even greater output from the four activities. While non-chemical restrictions on the dual-use list do not cause an overall decrease in manufacturing output, the non-chemical restrictions prevent the manufacturing sector from reaching it’s full productivity potential. The lowest output activities in the Gaza Strip deal restrictions on construction related items while the West Bank does not deal with equivalent restrictions. The dual-use goods list for the West Bank is the same in 2018 as in 2008; Israel has changed the Gaza Strip dual-use goods list three times since 2008. The Gaza Strip's lowest output manufacturing activities include the manufacture of leather, vehicles and trailers, machinery and equipment, and paper products (PCBS, 2009, pp. 91-92, 2019, pp. 117-118). The manufacture of vehicles, trailers, machinery, and equipment do not have access to construction related inputs due to the 2015 Gazan dual-use goods list (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2010). Specifically, Israeli restrictions on items such as, steel products, cables, resins, and sealants in 2010 with restrictions on welding equipment, winches, lifting equipment, copper, and aluminum products in 2015 limit the ability for Gazans to manufacture machinery, equipment, automobiles, and trailers (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2010; Gisha, n.d.). As both the lowest productivity West Bank and Gazan manufacturing activities list non-chemical items as key items to production the dual-use goods list restricts, the non-chemical restrictions reduce how much the lowest output manufacturing activities can increase output. As neither Gazan nor West Bank manufacturing industries commonly cite chemical items as products in the production process, the chemical items restrictions do not prevent output growth. The output of manufacturing sectors using construction-related materials decreased when Israel introduced additional construction or non-chemical items to the dual-use goods list. Manufacturing activities whose output decreased had used restricted construction materials as inputs for production. From 2009 to 2010, when Israel lifted the blockade, the output of manufacturing activities in the Gaza Strip increased from $158,323,400 to $316,646,800 as the blockade on the Gaza Strip limited all manufacturing sector’s access to inputs (PCBS, 2010, p. 91, 2011, pp. 119-120). As Israel’s 2015 expansion of the dual-use good list added Wood panels 1 cm thick and 5 cm wide, the output of furniture manufacturing decreased from $119,071,600 in 2015 to $57,412,500 in 2018 (PCBS, 2016, pp. 116-117, 2017, 2019, pp. 117-118). Manufacturing activities requiring heavy machinery such as electrical equipment manufacturing saw output decrease from 12,241,500 in 2015 to 10,322,100 in 2016; manufacturing of vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers output decreased from 6,737,400 in 2015 to 5,366,400 in 2016 (PCBS, 2016, pp. 116-117, 2017, p. 115-116). As multiple Gazan manufacturing activities’ output decreased after Israel introduced additional non-chemical items to the Gazan dual-use goods list, Israeli restrictions on non-chemical items prevent the Gazan manufacturing sector from attaining a higher growth rate than possible with the restrictions on non-chemical items. Therefore, an Israeli reduction of restrictions on non-chemical items would increase the output of the Gazan manufacturing sector. Palestinian Importation of Dual-Use Goods List ItemsIsrael does not completely block Palestinians from having dual-use list items. The IDF implements different levels of security screenings based on the dual-use good and subsequent destination. To import a dual-use goods list item into the West Bank, the Palestinian company applies for a transfer license from the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories’ (COGAT) Exceptions Committee (World Bank, 2019, p. 16). For a Gazan to import a dual-use goods item, the Israeli Customs Authority, Army, and intelligence service all screen the applying Gazan firm (The World Bank, 2019, p. 30-31). When companies import chemical products on the dual-use goods list, firms apply for “dealer permits” from the Israeli Civil Administration and Israeli Security Administration, who perform background checks on the firms (World Bank, 2019, p. 16). However, the IDF has not provided exact details on how Palestinian firms are to obtain a transfer license. Due to the vague description of items on the dual-use goods list, Palestinian manufacturers importing products are often unsure of particular items to declare as dual-use goods and therefore IDF personnel confiscate the dual-use goods without a license at Israeli-Palestinian checkpoints. While Palestinians can apply to import dual-use goods list items into the West Bank or Gaza Strip, the process is complicated and cumbersome. Licenses for Palestinians to import dual-use goods vary depending on the type of product and destination. The World Bank’sEconomic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee (2019) describes why Palestinians struggle to import dual-use items as COGAT accepted 95% of license applications for Palestinian companies to import dual-use goods in 2013; however, Palestinian companies only submitted 126 license requests. The World Bank labels the procedure for firms to get a license as a “long, nontransparent, and unpredictable.” Lastly, the license is only valid for 45 days and the company has to get permission from COGAT every time the company wants to import dual-use goods list items (World Bank, 2019, p. 16). As Palestinians find the process to obtain a permit as complicated, Palestinians will be less likely to import items on the dual-use goods list. The complicated nature of Israel’s dual-use goods permit policy means Palestinian importers don’t have an efficient mechanism to import dual-use goods list items. Costs to Palestinians of Importing into the West Bank from IsraelAt the Israeli Ports of Haifa and Ashdod Palestinian importers face multiple costs related to Israeli security policy. Foreign companies exporting to the Palestinian territories more often use the Israeli Ports than the Jordanian Port of Aqaba due to lower shipping costs at the Israeli Ports. Mustasim Elagraa, Randa Jamal, and Mahmoud Elkhafif in Trade Facilitation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Restrictions and Limitations (2014) describe security restrictions at Israeli ports as after a shipment enters the Port of Haifa or Ashdod, the Palestinian merchant makes an security check appointment with the Israeli Customs Authority and consequently waits one to seven days. At the security check, 70% of Palestinian imports go through a security scanning in electronic detectors while the Israeli Customs Authority either does not inspect or manually inspects the rest of imports. Costs to Palestinian importers from security screenings and manual inspections range from $210-$457 for smaller containers and $242-$484 for larger containers (see table 4) (Elagraa et al., 2014, pp. 14-18). Consequently, Palestinian manufacturers heavily reliant on imports are likely to spend a more revenue on security measures at Israeli ports. As foreign exporters more often ship products to the Ports of Haifa and Ashdod rather than the Port of Aqaba, Palestinian manufacturers reliant on imports are unlikely to be able to avoid the security costs.

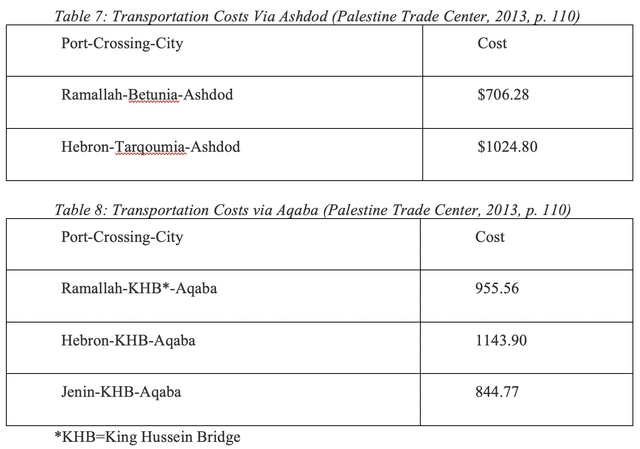

West Bank importers acquire high transportation costs due to the limited number of Israeli-West Bank crossings. Israel reduced the number of crossings into the West Bank when Israel constructed the Israeli-West Bank separation wall following the Second Intifada. The 712-kilometer wall separating Israel and the West Bank limits the flow of imports between Israel and the West Bank to a smaller number of commercial crossings (OCHA, n.d.c). The Palestine Trade Center (n.d.) notes Palestinian importers must take less efficient routes to and from the West Bank crossing at one of four commercial crossings: Tarqumia, Betunia, Sha’ar Ephraim, and Al Jalameh (Image 1). The four commercial crossings have specific infrastructural restrictions; specifically, the Taybeh Checkpoint only handles containers for imports while Tarqumia only handles stone shipment containers (Palestine Trade Center, n.d.). As a result, Palestinian importers have to spend extra time and resources traveling to a crossing able to handle the needs of the importer. As the Palestinian importer continuously accumulates extra transportation costs, the costs are likely to reduce the firm’s ability to invest in other business areas.

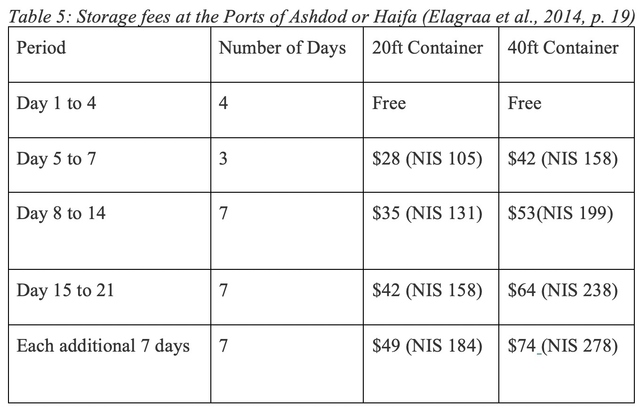

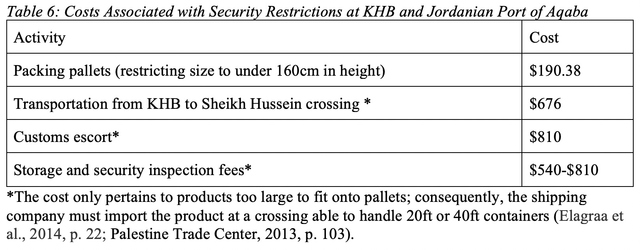

Moreover, at Israeli ports and Israeli-West Bank checkpoints, Israeli security checks cause delays and higher costs for Palestinian importers. Wait times and infrastructural limitations at Israeli-West Bank crossings result in higher costs at Israeli ports. At Israeli-West Bank commercial crossings, Palestinians importing goods unload shipments from Israeli trucks where Israeli security personnel inspect the cargo and then move the goods to Palestinian trucks (World Bank, 2008, pp. 7-8). As Elagraa et al. (2018) states, the commute from the Israeli ports to the checkpoints is two hours, shipments must leave the ports by 1:00 pm to cross the checkpoints before the crossings close at 5:00 pm. Because of security checks, health, and sanitary screenings, and the limited hours of Israeli-West Bank commercial crossings, Palestinians imports usually have to pay storage fees at Israeli ports (see table 5) (Elagraa et al., 2014, pp. 19-20). The combination of limited hours of Israeli-West Bank checkpoints, security screenings, and delays at Israeli ports means Palestinian importers dedicate multiple days to moving an import from Israeli ports to the West Bank. Despite the costs and wait times Palestinians face when importing through Israeli ports, imports fuel the Palestinian economy. As the Palestinian economy struggles to expand exports, the Palestinian territories maintain a high trade deficit. The Palestinian economy relies on imports as imports of goods and services accounted to 59.2% of Palestinian GDP in 2015 while exports were 18.3% of GDP (The World Bank, n.d., p. 8). Manufacturing activities in the West Bank and Gaza Strip imported $3,466,168 worth of products in 2008 and $6,539,590 in 2018 (PCBS, 2009, pp. 91-92, 2019, pp. 117-118). Since 2008 Palestinian companies have increasingly relied on imports for production; in the West Bank, the 3 largest manufacturing sectors: the manufacture of non-metallic mineral products, manufacture of food products, and manufacture of furniture had output increase 22%, 16% , and 33% from 2007 to 2018 (PCBS, 2019, p. 37). While the Palestinian economy already relies on imports, lowering security related costs on Palestinian imports would decrease costs for Palestinian manufactures. Consequently, a decrease in costs for Palestinian manufactures would boost the price competitiveness of Palestinian manufacturing products. Costs to Palestinians of Importing from Jordan to the West BankPalestinians moving products into the West Bank from Jordan face costs resulting from the infrastructural limitations of the Jordan-West Bank Crossing at the King Hussein Bridge (KHB). As the KHB is the only crossing between the West Bank and Jordan, the bridge facilitates most trade between the West Bank and Jordan. Because the security scanner at the KHB only handles products on pallets rather than larger shipping containers, merchants at the Port of Aqaba move products from large containers to pallets no taller than 160cm (Palestine Trade Center, 2013, p. 99). As the KHB cannot handle large containers, Israeli Customs personnel divert large imports to the Sheikh Hussein crossing 49 miles from the KHB; consequently, containerized imports incur extra storage, transportation, and Israeli customs fees (Elagraa et al., 2014, p. 22). In 2005 the IDF designated the Palestinian territory near the Damya Bridge Crossing a closed military zone; subsequently, the KHB faces higher traffic and wait times (Palestinian Shippers' Council, 2012, p. 5). The security infrastructure limitations at the KHB mean Palestinians really on Israeli ports when importing goods to large for pallets. Therefore, Israeli security policy directly results in higher costs for Palestinian imports coming through Jordan.

Imports coming into the West Bank from Israeli ports and the Port at Aqaba both face Israeli security restrictions but in different forms. The variance in security-related cost depends on the size of the import. If a product fits onto pallets, then the Palestinian company will face lower costs through Aqaba (only $190) vs either Israeli port (between $210-$484) (Tables 4 and 6). If the product cannot fit onto pallets, Palestinian firms importing through the Port of Aqaba face costs up to $2,296 (Table 6). Security-related costs at Israeli ports usually will not exceed $548 and depend upon the Israeli Customs Authority’s inspection technique of the import (see table 4) along with how long Palestinians store the product at port (see table 5). Therefore, the main security related cost decreasing the competitiveness of firms importing through Jordan vs Israel is inadequate security inspection infrastructure. Thus, the KHB needs a security scanner able to handle shipping containers to decrease the cost to Palestinians of using the Jordanian Port. While Palestinians face different security-related costs importing through Jordan vs Israel, Palestinians face a handful of common security measures regardless of port. Palestinians face common security measures at Israeli-West Bank and Jordan-West Bank crossings as Israeli security personnel staff all West Bank crossings. At both Israeli-West Bank and Jordanian-West Bank crossings, Palestinian importers unload products from Israeli or Jordanian trucks for Israeli security personnel to manually inspect and repackage into Palestinian trucks (Palestine Trade Center, n.d.). The manual security checks cause potential damage to goods, longer wait times, higher transportation costs, and spoilage of temperature sensitive goods as the checkpoints only provide unrefrigerated storage areas (The World Bank, n.d.). Lastly, Israeli personnel rather than PNA personnel perform security and operations on the Palestinian side of Israeli-West Bank and Jordanian-West Bank commercial checkpoints (The World Bank Group, 2017). Because of the security measures common at all West Bank crossings, Palestinian importers face some security related cost no matter the port a product enters from. Hence, an Israeli streamlining of the security inspection process would reduce costs and wait times at all crossings into the West Bank.

Despite costs due to security restrictions at Israeli ports, overall, Israeli ports are more attractive to shipping companies importing products to the West Bank. The Israeli ports are closer to Palestinian cities like Hebron, Ramallah, and Nablus. The Ports of Ashdod and Haifa are far cheaper than the port of Aqaba when the ship sails from African, American, or European ports. Additionally, the transportation costs to Palestinian cities is lower when the business imports from Israeli Ports vs Aqaba (see Table 7 and 8). When Palestinians import through Israeli ports Palestinian merchants do not have to worry about transferring products from containers to pallets as the Israeli-West Bank crossings are able to handle containers where the KHB cannot (Palestine Trade Center, 2013, p. 108). The higher security costs for containerized products through the Port of Aqaba with higher shipping costs for products going to the Jordanian port mean Palestinians overwhelmingly rely on Israeli ports to import products. Therefore, Palestinian importers are more likely to pay the security-related costs at Israeli ports. DiscussionDependency TheoryAs Israel collects Palestinian VAT and import taxes while maintaining a security presence around the Palestinian territories, the Palestinian economy is dependent upon Israel for funding and trade access. As Dependency theory outlines how unequal relationships between developed and developing states prevent economic growth in developing countries, the theory is useful to explain Israeli-Palestinian economic relations. Elkhafif et al. (2014) notes despite the 1994 Paris Protocol’s creation of an Israeli-Palestinian customs union, Palestinians cannot carry out customs operations as the Palestinian Authority (PNA) lacks a presence at border-crossing checkpoints and rely on Israel to collect VAT, customs, and import taxes. The customs union promotes Palestinian reliance on Israeli products while making foreign non-Israeli products more expensive as the PNA cannot lower the VAT more than 2% below the Israeli VAT (Elkhafif et al., 2014, pp. 9-10). The present study found Palestinian manufacturers when importing goods face Israeli security related costs whether the Port of entry is Israeli or Jordanian. As Israel’s control of Palestinian VAT and import tax collection allows Israel to control a major Palestinian revenue source, the PNA is dependent upon Israel to fulfill the PNA’s budget. Israeli security measures increasing costs for Palestinian importers shows the unequal customs relationship between Israel and the Palestinian territories negatively impacts Palestinian economic growth as dependency theory states. Israeli security related costs and exportation of low technology products to the Palestinian territories reduces Palestinian manufacturing competitiveness and benefits Israeli firms as dependency theory states. Israel’s use of its control of access to the West Bank to benefit Israeli firms while raising costs for Palestinian firms aligns with dependency theory’s explanation of how developed states may boost economic growth at the expense of developing states. Security-related costs do not hinder Israeli made imports because Israeli firms pay less in shipping costs and are not subject to the same security restrictions at Israeli Ports as other imports to the Palestinian territories (Bank of Israel, n.d.). Consequently, Israeli exports to the West Bank did not change when Israel implemented security restrictions due to the Second Intifada as imports from Israel were 70% of total imports before the Second Intifada in 1999 and 72% in 2006. (PCBS, 1999, pp. 38-45, 2006, pp. 46-51). Palestinian manufacturing GDP dropped from 21.2% of GDP in 1994 to 12.6% in 2007 (PCBS, 2003, p. 71, 2009, p. 73). Consequently, Israeli security restrictions on Palestinians benefited Israeli security and economic interests but decreased output potential of Palestinian manufacturing firms. Therefore, dependency theory clarifies how Israel’s presence in the Palestinian territories damages Palestinian economic growth potential but benefits Israeli security and economic concerns. Policy ImplicationsIsrael could reduce transport costs for Palestinian firms by equipping more checkpoints with necessary equipment to handle large imports and export loads. Israel needs to expand the number of checkpoints which can scan larger shipping containers. Containerization allows Palestinians to ship a larger number of products, decreases time spent at checkpoints, and reduces the amount of potential damage to goods (USAID, 2013, pp. 31). The Jordan-West Bank King Hussein Bridge (KHB) Crossing does not have the infrastructure to handle shipping containers while Israeli restrictions on which items Israeli security personnel can use in container scanners limits the use of container scanners at the Taybeh, Tarquima, and Al-Jalameh crossings (Palestine Trade Center, n.d.). A security scanner able to handle shipping containers at the KHB would mean Palestinians importing via Jordan using shipping containers would not have to spend $1,486 to transport goods via the Jordan-Israel Sheikh Hussein Crossing (Palestine Trade Center, 2013, p. 103). An Israeli expansion of security infrastructure to scan shipping containers would limit the number of trips a Palestinian firm would take to transport an equal amount of goods. A King Hussein Bridge Crossing able to handle shipping containers would reduce Palestinian reliance on Israeli ports. To increase manufacturing production in the Gaza Strip, foreign state and non-state donors need to increase funding to support Gazan electrical and fuel purchases. Egypt, Israel, and the Gaza Strip’s lone power plant supply the Gaza Strip with electricity. In 2019, the Gaza Strip had an average unfulfilled daily electricity demand of 263 megawatts due to fuel shortages at the Gazan power plant and a lack of funding for Gazan electricity purchases from Israel (OCHA, n.d.b). The present study found Gazan manufacturing output increases $41.24 when the amount of electricity a firm purchases increases $1. Offshore natural gas could provide fuel for the Gazan power plant as a European funded pipeline able to transfer 35 billion cubic feet of natural gas a year to the Gaza Strip is under construction; but until the pipeline is completed the Gaza Strip will need international donors to fund Gazan purchases of electricity and fuel (The Times of Israel, 2020). Expanded Gaza Strip electricity access and a subsequent reduction in the amount of power outages would allow Gaza Strip manufacturers to use electricity intensive modes of production and increase productivity. A larger supply of electricity in the Gaza Strip would improve living standards through expanding health, water, and sanitation services’ capabilities in the Gaza Strip. ConclusionPalestinians face costs due to increased wait times, limitations of security inspection infrastructure, increased transportation costs, storage fees, and security inspection costs because of Israeli security restrictions regardless of the port Palestinians use to import products. However, Palestinians face higher security costs importing shipping containers through the Jordanian port at Aqaba and lower security costs at the Jordanian Port if the import is shipped on pallets because the Jordanian-West Bank crossing does not have security scanning infrastructure capable to handle shipping containers. If the import can only fit onto shipping containers then the security related cost when Palestinians ship through the Jordanian Port of Aqaba can exceed $2,296 while the cost related to security shipping through the Israeli Ports will not exceed $548 depending on the security risk of the import. But when the import fits onto pallets, the security related costs are $190 through the Jordanian Port and $210-$548 through Israeli Ports. Although, the Ports of Ashdod and Haifa are cheaper than the Jordanian Port when the ship sails from African, American, or European ports. Due to security related costs and lower shipping costs to the Israeli Ports, Palestinians are dependent upon Israeli ports for trade facilitation. As Israel controls access into and out of the West Bank, Palestinian trade access is dependent upon the security concerns of Israel. ReferencesAdnan, W. (2015). Who gets to cross the border? The impact of mobility restrictions on labor flows in the West Bank. Labour Economics, 34, 86-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2015.03.016 Al-Falah, B. (2013). Structure of the Palestinian Services Sector and Its Economic Impact. Palestinian Economic Policy Research Institute. Bank of Israel. (n.d.). Trade links between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. https://www.boi.org.il/he/NewsAndPublications/PressReleases/Documents/Israel-Palestinian%20trade.pdf BBC (2012, September 24). Israel plans work permits for 5,000 Palestinians in West Bank. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-19701090 Berends, G. (2008). Fear and Loading in West Bank/Gaza: The State of Palestinian Trade. Journal of World Trade, 42(1), 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00632.x Brym, R. J., & Araj, B. (2008). Palestinian Suicide Bombing Revisited: A Critique of the Outbidding Thesis. Political Science Quarterly, 123(3), 485–500. B’Tselem. (n.d.). Fatalities in the first Intifada [table]. https://www.btselem.org/statistics/first_intifada_tables B’tselem. (2017, November 11). Hebron City Center. https://www.btselem.org/hebron Cali, M., & Miaari, S. H. (2018). The Labour Market Impact of Mobility Restrictions: Evidence from the West Bank. Labour Economics, 51, 136-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.12.005 Central Intelligence Agency. (2020a, January 30). The World Factbook: Gaza Strip. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gz.html Central Intelligence Agency. (2020b, January27). The World Factbook: West Bank. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/we.html Cohen, R. S., Johnson, D. E., Thaler, D. E., Allen, B., Bartels, E. M., Cahill, J., & Efron, S. (2017). https://doi.org/10.7249/RB9975 Daoudi, H., & Khalidi, R. (2008). The Palestinian War-Torn Economy: Aid, Development and State Formation. A Contrario, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.3917/aco.052.0023 Dos Santos, T. (1970). The Structure of Dependence. American Economics Review, 40(2), 231-236. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:aea:aecrev:v:60:y:1970:i:2:p:231-36 Elagraa, M., Jamal, R., & Elkhafif, M. (2014). Trade Facilitation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Restrictions and Limitations (pp. 1–43). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Eljafari, M. (2010). Palestinian Capacity Building Needs in Trade Policy and Trade Facilitation. The Journal of World Investment & Trade, 11(5), 731-751. https://doi.org/10.1163/221190010X00383 Elkhafif, M., Misyef, M., & Elagraa, M. (2014). Palestinian Fiscal Revenue Leakage to Israel under the Paris Protocol on Economic Relations (pp. 1–58). United Nations. Egeonu, P. (2017). Third World Dependency, Theoretical Assumptions and African Underdevelopment: A Critique Analysis. Online Journal of Arts, Management and Social Sciences, 2(2), 16–28. Gisha. (n.d.). Controlled dual-use items – in English. Gisha. Gisha. (2016). Dark-gray lists. (pp. 1–6). Gisha. https://gisha.org/publication/4860 Haddad, T. (2018). Palestine Ltd.: Neoliberalism and Nationalism in the Occupied Territory. I.B. Taurus. Israeli Defenses Forces, (n.d.). The Gaza Tunnel Industry. https://www.idf.il/en/minisites/hamas/hamas/the-gaza-tunnel-industry/#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20most%20pressing,the%20cost%20of%20civilian%20rehabilitation. International Monetary Fund. (2018). West Bank and Gaza Report to the Ad Hoc Liason Committee. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2018/09/17/west-bank-gaza-report-to-the-ad-hoc-liaison-committee Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2010, July, 04). Gaza: Lists of Controlled Entry Items. https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/peace/humanitarian/pages/lists_controlled_entry_items_4-jul-2010.aspx Lloyd, R. B. (2012). On the Fence: Negotiating Israel's Security Barrier. The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 3(2), 198-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2012.741039 Mansour, H. (2010). The Effects of Labor Supply Shocks on Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Labour Economics, 17, 930-939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2010.04.001 Marcus, R. D. (2017). Learning ‘Under Fire’: Israel’s improvised military adaptation to Hamas tunnel warfare. Journal of Strategic Studies, 42(3-4), 344-370. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2017.1307744 Nashashibi, K., Gal, Y., & Rock, B. (2015). Palestinian- Israeli Economic Relations: Trade and Economic Regime. Office of the Quartet Representative. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (1999). Registered Foreign Trade Statistics Goods and Services, 2018 Main Results (pp. 1–208). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2003). National Accounts at Current and Constant Prices - (1994-2000), (pp. 1–101). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2006). Registered Foreign Trade Statistics Goods and Services, 2018 Main Results (pp. 1–85). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2009). Economic Surveys Series, 2008 Main Results (pp. 1–144). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Economic Surveys Series, 2009 Main Results (pp. 1–145). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2011). Economic Surveys Series, 2010 Main Results (pp. 1–182). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Economic Surveys Series, 2015 Main Results (pp. 1–179). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Economic Surveys Series, 2016 Main Results (pp. 1–183). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Economic Surveys Series, 2018 Main Results (pp. 1–186). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Palestinian Labour Force Survey Annual Report: 2018 (pp. 1–138). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. (2019). Registered Foreign Trade Statistics Goods and Services, 2018 Main Results (pp. 1–157). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/pcbs_2012/Publications.aspx Palestinian Shippers' Council. (2012). Capacity Development For Facilitating Palestinian Trade A Study on the Proposed Mobile Scanner at King Hussein Bridge (pp. 1–31). Palestinian Shippers’ Council. Palestine Trade Center. (n.d.). Export Processing Path through Internal Commercial Crossings. https://www.paltrade.org/en_US/page/export-processing-path-through-internal-commercial-crossings Palestine Trade Center. (2013). Exporting and Importing Via Jordanian and Israeli Ports Comparison Study (pp. 1–128). https://www.paltrade.org/en_US/page/sector-product-studies Pressman, J. (2003). The Second Intifada: Background and Causes of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Journal of Conflict Studies, 23(2). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JCS/article/view/220 Samhouri, M. (2016). Revisiting the Paris Protocol: Israeli-Palestinian Economic Relations, 1994–2014. The Middle East Journal, 70(4), 679-607. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/634691. Shrum, W. (2001). Science and Development . International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03165-X Smith, C. D. (2017). Palestine and the Arab-Israeli conflict a history with documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins. Springer, J. E. (2015). Assessing Donor-driven Reforms in the Palestinian Authority: Building the State or Sustaining Status Quo? Journal of Peacebuilding & Development,10(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2015.1050796 The Times of Israel. (2019, May 26). Israel re-expands Gaza fishing zone to 15 nautical miles. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-re-expands-gaza-fishing-zone-to-15-nautical-miles/#:~:text=Israel%20announced%20Saturday%20night%20that,from%20the%20coastal%20Palestinian%20territory. The Times of Israel. (January, 12, 2020). Israel pushes forward with plans for new gas pipeline to Gaza – report. (n.d.). https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-pushes-forward-with-plans-for-new-gas-pipeline-to-gaza-report/ the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). (2017a, October 28). UNRWA Condemns Neutrality Violation in Gaza. https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/official-statements/unrwa-condemns-neutrality-violation-gaza the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). (2017b, June 09). UNRWA Condemns Neutrality Violation in Gaza in the Strongest Possible Terms. https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/press-releases/unrwa-condemns-neutrality-violation-gaza-strongest-possible-terms The World Bank. (n.d.). Unlocking the Trade Potential of the Palestinian Economy (pp. 1–116). The World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/960071513228856631/unlocking-the-trade-potential-of-the-palestinian-economy-immediate-measures-and-a-long-term-vision-to-improve-palestinian-trade-and-economic-outcomes The World Bank. (2019a). Palestine's Economic Update — October 2019. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/westbankandgaza/publication/economic-update-october-2019 The World Bank. (2019b, April 17).World Bank Calls for Reform to the Dual Use Goods System to Revive a Stagnant Palestinian Economy. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/04/17/world-bank-calls-for-reform-to-the-dual-use-goods-system-to-revive-a-stagnant-palestinian-economy The World Bank Group. (2017). Unlocking the Trade Potential of the Palestinian Economy. Washington D.C.: The World Bank Group. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/960071513228856631/unlocking-the-trade-potential-of-the-palestinian-economy-immediate-measures-and-a-long-term-vision-to-improve-palestinian-trade-and-economic-outcomes United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2013). Report on Unctad assistance to the Palestinian people: developments in the economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory (pp. 1–19). Geneva. UNData. (n.d.). State of Palestine. https://data.un.org/en/iso/ps.html United Nations (n.d.). The Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism. Retrieved from https://grm.report United Nations Office for Project Services. (n.d.a). GRM. https://grm.report United Nations Office for Project Services. (n.d.b) The GRM Process. https://grm.report United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Occupied Palestinian territory (OCHA). (n.d.a). Data on casualties. https://www.ochaopt.org/data/casualties United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). (n.d.b). Gaza Strip electricity supply. https://www.ochaopt.org/page/gaza-strip-electricity-supply United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Occupied Palestinian territory (OCHA). (n.d.c). West Bank Barrier. https://www.ochaopt.org/theme/west-bank- barrier USAID. (2013). Trade Facilitation Project (pp. 1–52). USAID. World Bank. (2008). West Bank and Gaza Palestinian Trade: West Bank Routes (pp. 1–29). World Bank. World Bank. (2019). Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee (English) (pp. 1-41). World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/westbankandgaza/publication/economic-monitoring-report-to-the-ad-hoc-liaison-committee-april-2019 Zilber, N., & Al-Omari, G. (2018). State With No Army Army With No State. Washington D.C.: The Washington Institute For Near East Policy. washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/state-with-no-army-army-with-no-state Zilberfarb, B.-Z. (2018). The short- and long-term effects of the Six Day War on the Israeli economy. Israel Affairs, 24(5), 785–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2018.1505476 Endnotes1.) The dual-use goods list consists of items the Israeli Government thinks Palestinians could use “for the development, production, installation or enhancement of military capabilities” in addition to the civilian use of the item (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2010). Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |