From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 5 NO. 2The War Lovers (Again): What the Foreign Policy Advisers of Presidential Candidates May Tell Us About Future U.S. Foreign Policy

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

Evan Thomas's recent book, The War Lovers, chronicles the "monumental turning point" of the U.S. declaration of war against Spain in 1898, and the small circle of men who pressed for war, and for an American empire. The central figures, for Thomas, were Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy; his friend Henry Cabot Lodge, hawkish senator and foreign policy adviser to President McKinley; and William Randolph Hearst, editor of the New York Journal, whose paper did its upmost to fan war fervor in 1897-8. These men were inspired by, and had the strong support of Alfred Thayer Mahan a naval officer, history professor, and influential author of The Influence of Sea Power Upon History. Though President McKinley hesitated about war with Spain, Roosevelt and Lodge had long dreamed of a war that would establish the United States as a major player on the world stage. When another prominent politician, Speaker of the House Thomas Reed, opposed substantial increases in naval funding that he thought "invited conflict," Lodge promptly accused him of harboring "extreme pro-Spanish prejudices."1 The U.S. did declare war on Spain in 1898, won a six-months war, and then became bogged down for 14 years in a war against Philippine insurgents who had expected independence after Spain's defeat. In the process of "pacifying" the insurgency, the occupation officers developed methods of surveillance and torture that Americans would use again, both in the U.S. and abroad.2 The episode calls up obvious analogies. In other times there have been enthusiastic, often romantic war advocates who discounted the risks and costs of wars--wars that seldom turned out as the "war lovers" intended. Three Varieties of Engagement with the WorldFrom at least 1898, one finds in U.S. foreign policy three distinct threads of argument and action propagated by presidents and their circles of advisers: unilateralist expansionism (as in the RooseveltLodge argument for the Spanish American war); isolationism (represented by, among others, Speaker of the House, Thomas Reed); and the more recent liberal internationalism enunciated (if not always practiced) by Woodrow Wilson. The three doctrines are not always easy to label and disentangle, of course.3 Nevertheless, the point cannot be missed that small circles of advisors, chosen by presidents precisely because they share with him fundamental perspectives on the world, often become very influential sources of foreign policy advice. And whether or not the president subscribes overtly to unilateralist principles, presidents since 1946 have engaged in many wars, most without congressional declarations, and many without any real consultation with allied democracies or even the U.S. Congress. These facts draw our attention to the advice groups that support presidential foreign policy stances. The most notable since WWII have been the group of well-educated and urbane "Wise Men" who guided the postwar transition to U.S. superpower status and Cold War in the 1940s;4 the architects of the Vietnam War in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations,5 and the George W. Bush advisors (including the Vice President) who planned and executed the "global war on terror."6 From the beginning of American world power to the most recent stage of hegemonic dominance, these four groups were all men (with the exception of Condoleezza Rice in the Bush advisory group) who aspired to make their country powerful, and who themselves clearly relished the power that came with designing a new world. But there are critical differences. The first group of architects (the 1898 empire builders around TR) and the fourth (the 2001 Bush advisors, or "Vulcans" as the core group called themselves), represent episodes of nationalist unilateralism in Republican administrations. The second group of advisers, The Wise Men (as historians have dubbed them) were different, internationalists of a more cooperative bent, whether because they had just seen a cataclysmic war won by a determined alliance of democracies, or because the years after 1945 were clearly both transitional and critical (if war focuses the mind, so does making a lasting peace amid the rubble). They served a Democratic administration in which the Wilsonian commitment to multilateral, institution-centered internationalism was still a constraint on unilateralism. In addition, the two aggressively unilateralist advisory groups (of 1898 and 2001) saw the military as the central institution of American foreign policy. The Wise Men of 1946 who constructed (with a lot of help) the post-war world saw alliances, diplomacy and new international institutions as the central mechanisms of U.S. influence in the world. If the first and last advisor groups were War Lovers, the Wise Men were not. They were not dewy-eyed pacifists, by any means. They were tough-minded, hard-eyed calculators of national advantage at a time when U.S. economic interest and the goals of rebuilding Europe, integrating the world economy, creating new rules to deter war, and democratizing the defeated Axis nations were all quite compatible. But, however suspicious they were of the communists who by late 1946 were morphing into designated national enemies, and however narrow the vision developed in their mostly privileged families and toney universities, the 1946 cohort of foreign policy advisors were far more flexible in their strategic calculations, and the end-states they worked toward, than the 1898 empire builders, the Vietnam architects of 1964-68, or the Bush Vulcans of 2001. Even by the time they became, in the most fundamental way, anticommunists, the Wise Men differed from the first group by being less motivated by capitalist exigencies, and from the last group, by being less ideological. As Isaacson and Thomas describe the 1940s group, "ideological fervor was frowned upon; pragmatism, realpolitik, moderation, and consensus were prized. Nonpartisanship was more than a principle, it was an art form."7 Thus it seems accurate to say that the Wise Men, though they served a Democratic president, were less partisan than the two unilateralist groups, which contained few if any members from the other party and did not value pragmatic non-partisan collaboration. The words "partisan," and "ideological" have different implications. While partisanship may lead to policy gridlock (IF it strongly coincides with ideological fervor, which is not always the case), and may have other unfortunate consequences, ideologues make more worrisome foreign policy advisors. Or so argues political scientist Thomas Langston.8 Why Ideologues Make the Most Dangerous Foreign Policy AdvisersLangston has constructed an insightful typology that distinguishes partisans, ideologues, and other "people with ideas" who fall in neither of those camps. Many people interested in policy find a place in government because they have ideas for programs, usually centered on a set of goals that are valued by their party, and they have a set of logical means to achieve them. Many of these people are academics, technocrats, or simply pragmatists who have worked in real-world settings, in experimental ways, and want to carry those lessons and methods to the national level. But ideologues are more than just people with ideas. They are people of ideas. And that is the characteristic that can make them dangerously inflexible and closeminded, certain that the ends they insist upon justify whatever means can accomplish them.9 Regular partisans are seldom as inflexible as ideologues; they want to win elections. Ties to the general electorate give partisan officials a grounding in popular politics that ideologues in think tanks usually lack. Academics, whose numbers in government increased after the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, usually plan to return to their universities after government service, and, one might suggest, want to protect their scholarly reputations from charges of extremism; tenure demands may also act to moderate extremism, as do classes full of questioning students. Ideologues, on the other hand, live their lives surrounded by other ideologues, often in think tanks that are far more insulated than universities or campaigns and elected offices. In Langston's definition, "ideologues" are people of ideas who:

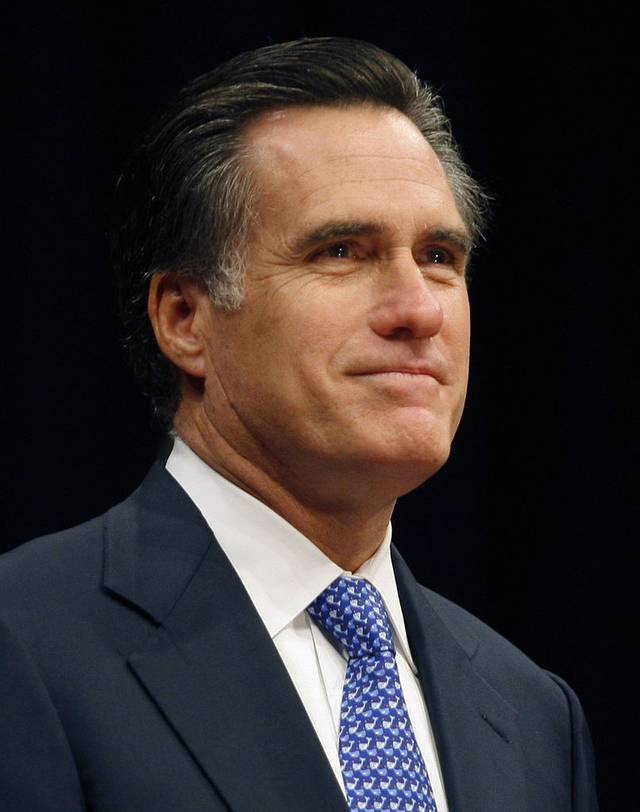

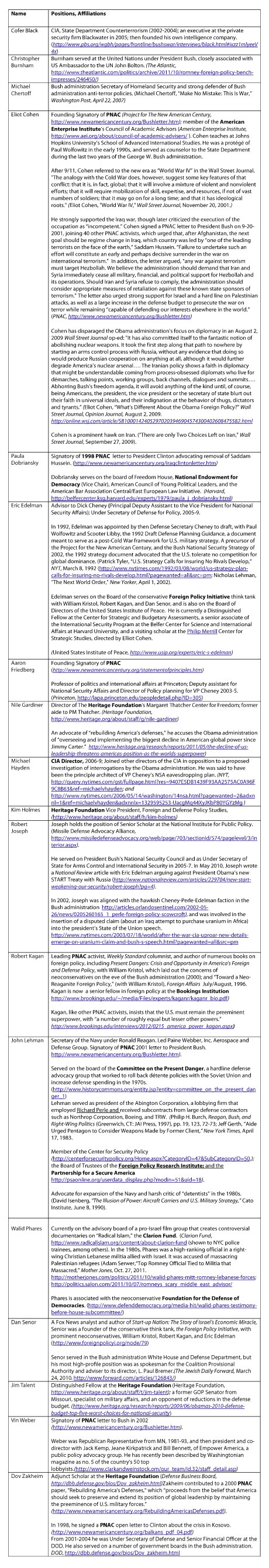

President Reagan and the Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev at a morning meeting in the Oval Office during the Washington Summit in December of 1987. Thus, ideologues value end-states above process, and adhere closely to those endstate values, even in the face of changing circumstances and new information. They are not very open-minded, in part because they do not have to be. They spend much of their time in think tanks and media outlets with like-minded pe ople, and are clever enough to insinuate themselves, in a kind of "chain migration" into presidential administrations where they may achieve great influence. The Expansion, Defeat, and Return of IdeologyThe number of ideologues in the executive branch has grown remarkably since the late 1970s. The essential cause is probably found on the supply-side: the growth of think tanks funded by a new breed of strongly ideological foundations. The total number of independent think tanks increased by over 400 percent between 1970 and 2001.11 Favorable tax incentives for contributions to nonprofits, dissatisfaction with the Carter administration, and particular unhappiness among businessmen and hawkish intellectuals about increasing regulation and taxes, post-Vietnam military cutbacks, and rising criticism of Israel after 1967-all these developments facilitated the expansion of conservative think tanks.12 The new think tanks differed from earlier ones by their overt political advocacy, according to the author of the major recent study of think tanks. Rather than focusing on the scholarly research and policy analysis encouraged by earlier funding sources (particularly the older Ford and Rockefeller foundations), the new breed of think tanks were aggressively ideological. As Andrew Rich reports, the large majority of think tanks in 1996 were "avowedly ideological" (165 of the 306 in his study, or 54%), and two thirds of those were conservative. Furthermore, "the rate of formation of conservative think tanks (2.6 each year) was twice that of liberal ones (1.3 each year).13 As the older foundations began to decline funding requests from think tanks with a political cast, the new conservative foundations—like the Bradley, Smith Richardson, and Sarah Scaife foundations-demanded active promotion of conservative economic and foreign policy ideas. And the difference in orientation to political advocacy ("aggressively promoting their ideas") is what has made the conservative think tanks so much more influential, according to Rich.14 By the 1990s, the largest think tanks, measured by annual budgets, included the Heritage Foundation, The American Enterprise Institute, and the Brookings Institution, all with budgets of around 20-25 million dollars, and the Urban Institute, with a budget of over $55 million. The first two were categorized by Congressional Quarterly's Public Interest Profiles as "conservative," the Brookings Institution as liberal. The Urban Institute last was classified by PIP as "politically balanced" or "non-partisan."15 Arguably the largest think tank of all is the Rand Corporation, founded in 1946 (and made independent of the Defense Department two years later) to produce technological and strategic policy studies for the armed services. It is still (like the Urban Institute) a major recipient of government contracts.16 If Rand were classified as a think tank, it would be listed on the conservative side, based on its policy orientations and funding sources; indeed, several prominent hawkish ideologues have been affiliated with Rand, as was an important neoconservative mentor, Albert Wohlstetter, a mathematician and strategic analyst.17 But even without Rand, growth in the 1980s and 1990s was robust for the 11 wealthiest conservative think tanks, leaving them with significantly more assets than the 11 wealthiest liberal institutions by the early 2000s.18 South Carolina State Treasurer Curtis Loftis campaigns with Gov. Mitt Romney during a September 2011 event in North Charleston, South Carolina. The Reagan administration was the first to reflect the surge in conservative think tanks. Langston describes it as the most ideological presidency in American history.19 Its closest competitor, the administration of Franklin Roosevelt (the previous realignment leader), was leavened with partisans, social workers, and competing ideologues, making its "ideological density" less notable. It is not surprising that a president with little experience in foreign policy would be willing to rely on a network of ideologues that could furnish ideas and rationales for his hawkish foreign policy orientation. One may perceive a pattern in the reliance of inexperienced presidents on ideologues, one that connects the Reagan and G.W. Bush administrations but skips the administration of the more experienced and assured George H. W. Bush. The Reagan administration, then, on taking office, reflected the "supply side" growth of available conservative ideologues from the new aggressively conservative think tanks. He also recruited heavily from a group of Cold War hawks that came together to protest cuts in the defense budget (The Committee on the Present Danger).20 Prominent among them were Richard Perle, Fred Ikle (both in Reagan's Defense Department), Eugene Rostow (an opponent of arms control appointed to head the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency), and John Lehman, Jr.(Secretary of the Navy), all colleagues from the CPD; and William Casey, heading the CIA. All were, to put it mildly, "opponents of détente." Casey, according to his executive assistant, Robert Gates, saw his purpose there as "primarily to wage war against the Soviet Union."21 The administration did have its share of divergent ideologues and traditional partisans, but the Iran-Contra scandal illustrated the potential for disaster when weakly supervised ideologues run amok. In the last years of his administration, however, Reagan abandoned the strident bellicosity and brinksmanship of the first three years and entered negotiations with the Soviet leader that led, in 1987, to the most important nuclear arms control treaty of the Cold War. The new Reagan posture allowed Gorbachev the maneuvering room to introduce dramatic reforms without fear of attack from the U.S., and then to dismantle the Soviet empire itself. But before that happened, the most inflexible foreign policy advisers left the Reagan administration in disgust, allowing relieved pragmatists to do their momentous work unimpeded.22 The resurgent hawks have apparently pinned their hopes on Romney. The end of the Cold War removed the major rationale for a highly militarized foreign policy, leaving the Reagan-era hawks rather at sea. They returned to their think tanks to regroup and await a new opportunity.23 That opportunity arrived in 2001. The George W. Bush administration was a second act for the extreme hawks. The modalities and apocalyptic discourse of the Cold War were easily adapted to a long-term war on terror. The neoconservatives, brought into the administration by Vice President Cheney, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, and Cheney's former DOD colleague, Paul Wolfowitz, recruited scores of like-minded people to manage the administration's foreign policy. President Bush wryly apologized to AEI for stripping its ranks of over 20 conservative thinkers for his administration.24 Bill Kristol boasted that every week one of the Vice President's aides dropped by the Weekly Standard offices to pick up 30 copies.25 The results of the ideological occupation of the executive branch in 2001 are well known. The Bush administration mismanaged two costly wars, each longer than any before 2001; launched a final surge of deregulation that freed financial institutions to take excessive risks; and cut taxes sharply during war (for the first time in American history). The U.S reputation abroad fell dramatically, debt mounted, and deaths rose.26 One might have thought that the conservative ideologues would quietly return to their think tanks after 2008 and keep a low profile. But surprisingly, they began to reappear in 2010. The Republican Party, grown even more conservative, surged back in the low-turnout midterm elections as the economy recovered too slowly and the health care, financial reforms, and economic stimulus policies angered conservatives. The ideologues who had guided a disastrous foreign policy and presided over an economic debacle again appeared in policy debates, and on university lecture circuits. In 2012, the Republican primary contenders were anything but contrite about the Bush record. The war lovers were back. The Foreign Policy Advisers of Mitt RomneyOn foreign policy, the 2012 Republican contenders exhibit few differences. All but Ron Paul favor expanding, rather than contracting, military budgets, bases, troops, and weapons systems. The three major candidates (Romney, Santorum, and Gingrich) would slow withdrawal from Iraq and Afghanistan, reduce cooperation with international institutions, cut foreign aid, and offer uncritical support for Israel. The candidates (except for Paul) express no hesitation about the possibility of a new war with Iran, and criticize President Obama for pursuing diplomacy. But the resurgent hawks have apparently pinned their hopes on Mitt Romney. His team of foreign policy advisers announced in 2011 abounds with hawks from the Bush and Reagan administrations.27 In introducing the group, Romney appeared to consciously use language that echoed the1990s Project For The New American Century, whose grand plan, first proposed in 1992, would assure U.S. global dominance with reliance on an unchallengeable military able to preempt any competitors: "I am deeply honored to have the counsel of this extraordinary group of diplomats, experts, and statesmen. Their remarkable experience, wisdom, and depth of knowledge will be critical to ensuring that the 21st century is another American Century."28 Table I lists the affiliations and experience of Romney's most notable advisers. Almost all are linked to the most conservative think tanks—PNAC, AEI, Heritage, and PNAC's successor, The Foreign Policy Initiative; some have multiple affiliations. In view of the biographies of the Romney foreign policy team, and the Republican consensus on major issues, it seems reasonable to conclude that if he is elected, his administration will be predisposed to return to the foreign policy ideas and policies of the Bush administration. As a candidate with little foreign policy knowledge or experience, Romney may follow the Reagan-Bush pattern of relying on ideological networks for administration staffing and policy development. Most contemporary foreign policy hawks have not engaged in war themselves, but show the same enthusiasm for military prowess, and the same lack of attention to costs as earlier ideologues. It has been common among the Bush administration advisers to defend war expenditures and deaths as quite modest in comparison to previous wars. In an NPR debate on U.S. foreign policy in 2011, Romney's most prominent advisor, Eliot Cohen, noted that "The United States today spends something on the order of about five percent of Gross Domestic Product on defense, maybe a little bit more. During the Kennedy administration, that figure was over eight percent, during the Eisenhower administration, over 10 percent." He argued that domestic social spending was a far greater budgetary concern than military spending.29 Cohen's debate partner, Elliott Abrams, argued that the military budget had already taken "great hits" and that further cuts would benefit U.S enemies and threaten its role in the world, making the entire world less safe. And, he argued, "there are hundreds of millions of people around the world who rely on American power for their safety." He defended the moral purpose of the war in Iraq, and referenced the nation-building successes in Germany and Japan after WWII as analogies. As for the human costs of war, Eliot Cohen noted that "Using force is a terrible thing. You're going to kill innocent civilians. You're going to make mistakes. You'll probably get some of your own people killed. And those are real people. Are you going to avoid something worse? That's really the fundamental reason why we do go to war, and we should go to war." Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Adm. Mike Mullen listens to Commanding Officer of Riverine Squadron One, Cmdr. William J. Guarini Jr., explain the features of the combat vest during a visit of Riverine Group One (RIVRON-1) and Riverine Squadron One on board Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek. Cohen has criticized the deficiencies of counterinsurgency policy in both the Bush and Obama administrations and suggested that a better model for the occupations that follow American wars can be found in the most controversial policy of the Reagan administration. Applied in Central America to shore up right wing dictators and fight insurgencies through surrogates—Americantrained and armed soldiers and paramilitaries-this strategy has been dubbed the "El Salvador Option" by Cohen and others. It has suggested to some critics the resurrection of a policy that supported conservative, pro-American dictatorships, terrorized civilians and political dissidents in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, and lead to the deaths of thousands, from entire peasant villages to Archbishops murdered while saying mass.30 "We did counterinsurgency very well in Salvador," Cohen has said;31 In a late2009 article featured on the AEI web site, Cohen continued to tout the Salvador Option as a promising strategy for dealing with insurgencies.32 War hawks now press for preventive war on Iran, either on U.S. initiative, or in the course of U.S. backing for an Israeli strike. Their war campaign again suggests overoptimistic assumptions about the speed and efficacy of bombing to prevent Iran's acquisition of nuclear weapons, and little concern for the risks and costs of war.33 Their arguments, and the drumbeat of exaggerated threat echoed in the media, recall similar arguments made for the Iraq war in 20023. In the present Iran case, as in Iraq, there is insufficient intelligence about the nuclear program, and insufficient examination of what it would mean for the United States or Israel (the principle advocate of such an attack) if Iran DID develop nuclear weapons. Diplomatic initiatives are again given too little weight by war advocates. If Iran's nuclear program is a response to prolonged threats from Israel and the United States, then nonaggression pledges and moves toward a denuclearization of the Middle East (including Israel) merit serious consideration. At the least, multilateral diplomatic negotiations-of the sort that were successful in persuading Libya to abandon its nuclear and chemical weapons programs—should be undertaken as alternatives to war.34 But is there reason to fear that the bellicose rhetoric of a presidential candidate with a team of very hawkish foreign policy advisers will inevitably, if elected, lead the country into more unnecessary wars, and favor military force over "soft power" in foreign policy? Should campaign rhetoric be taken seriously as an indication of foreign policy strategies and goals? Political science theory suggests that there is. First, there is the consistent finding that presidents do devote their first two years (at least) to the achievement of the policy platforms on which they run.35 That may well be, as Rahul Desai has argued, a major reason for midterm losses.36 And the prospect of midterm and presidential year losses at the polls tempts presidents to "diversionary war."37 But Benjamin Fordham adds plausible complexity to his study of diversionary war: party difference. Democratic presidents, he shows, are more likely to go to war when inflation is high; Republicans, when unemployment is high. The rationale rests on left-right party differences in democracies around the world. The left party is more concerned with unemployment, which its constituents experience more than the affluent constituents of the right party. If unemployment is high, Democratic presidents will meet it with stimulus and social welfare programs. However, if inflation is high, that won't be as feasible. Shorn of opportunity to enact its favored domestic policies, Democratic presidents will then go to war to distract the public from economic woes and elicit a rally effect. Republican constituents do not favor stimulus policies; So, if unemployment is high, they will instead go to war. Different economic problems carry different risks of war, depending on the party of the President. The evidence shows that there is, in fact, evidence of such patterns in the many wars presidents initiate.38 If Romney wins, adopts stringent deficit-cutting policies and cuts social spending to pay for the large military he and his foreign policy advisers have pledged to support, a slide back into recession would be an occasion for diversionary war…. which would doubtless have the approval of the hawkish advisers, who would wrap ideological goals in electoral interest . The neoconservative Iraq war initiative was, in fact, justified by President Bush's political adviser and GOP leaders as a way to forestall midterm election losses in 2002.39 Stephen Skowronek's theory of the presidency40 seems to predict that an "articulator" (a president who is affiliated with the "regime" (dominant) party—clearly the Republicans now—will be more warlike than presidents in other "political times." These post-realignment presidents face increasing tensions within their party coalitions and also personal frustrations with the obligations of the "faithful son" to the regime founder. They are anxious to break out and make a record for themselves, while uniting their increasingly restive party. War serves both purposes. Romney would be an articulating president, in Skowronek's scheme. Finally, my own concept of "novice macho" argues that new presidents, especially those who have no military experience, will, in their first year, initiate a military attack to prove their mettle. For Obama, it was a dramatic obliteration of a group of Somali pirates. For Clinton, it was bombing Iraq early in 1993. For George W. Bush, of course, it was war in Afghanistan. For Romney, the most likely pre-election target, given his advisors and his own statements on Iran and Israel, would be an attack on Iran: unilaterally, or by backing up an Israeli attack. If, on the other hand, Obama is reelected and Israel does not initiate an attack on Iran, he will be unlikely to start that war. Its risks are great; his foreign policy advisers, both civilian and military, do not favor a third war, and a spiking oil price will slow recovery— which is his main ticket to reelection. A careful 1993 study of presidential war-making, in another honors thesis at this university, demonstrated that if presidents are going to make war in their own reelection year, it will likely be in the first six months of the year, becoming less likely in the six months before the election. The later restraint seems to arise from fear of provoking opposition from Americans suspicious of a politicallymotivated war. Should Obama be reelected without involvement in a third war, which is probably his preference, war becomes steadily less likely in the second term. The last two years of an eight-year presidency are the most peaceful of all. Presidents no longer have electoral incentives to make diversionary wars, and are likely to be concerned with leaving a positive legacy.41 This is probably the reason that George W. Bush resisted entreaties from Israel to attack Iran during his last two years. Instead, he pursued new foreign aid programs and diplomatic negotiations with North Korea and Libya.42Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Political Science |