From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 5 NO. 2The Awakening: How Revolutionaries, Barack Obama, and Ordinary Muslims are Remaking the Middle East

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2012, Vol. 5 No. 2 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

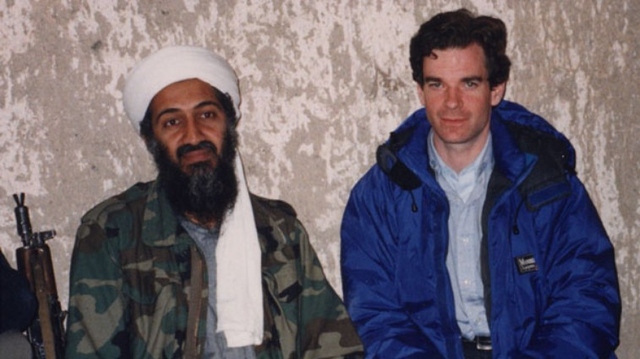

I will begin with Osama Bin Laden, because I'm one of the few people to have met him, which will remain the case going forward. When we interviewed him in 1997, he said a number of things to us, which I think represent kind of an alternative vision of the Middle East that most Muslims have projected. And this vision you know during the course of this interview, which was difficult to arrange. He declared war for the first time against the United States, which was somewhat surprising. We didn't expect him to do that. Imagine if the Japanese in 1937 had gone on RKO or NBC and said, you know, "we are planning to attack the United States." Imagine how the events of Pearl Harbor might have turned out rather differently. Bin Laden warned us, and we just didn't process what he was saying very well. Partly of course because he wasn't a representative of the state, we didn't really understand that non-state actors, or AlQaeda groups, could inflict significant damage on us. Of course, on 9/11, AlQaeda did more damage in the morning than the Soviet Union had done directly to the United States during the decades of the Cold War, that was an unexpected development. So why were we attacked on 9/11? What was Bin Laden trying to achieve? Did he achieve any of his goals? One, why were we attacked? When Bin Laden talked to us in March of 1997, we asked him "why are you declaring war on the United States?" There were a lot of things he didn't say. He didn't say, "I'm attacking you because of your freedoms, I'm attacking you because of the first amendment, I'm attacking you because of the Supreme Court, I'm attacking you because of Hollywood, I'm attacking you because of your policies on homosexuals, I'm attacking you because of feminism," he didn't mention any kind of cultural issue at all. It was a foreign policy critique of the United States and basically there were four reasons that he said that he was attacking us. One, US support of Egypt and Saudi Arabia, regimes that he didn't think were sufficiently Islamic. Two, US support for Israel. Three, US support for sanctions against Iraq which were then in place. Those were his key issues. When we asked him "are you planning to attack American soldiers or American civilians" he said, "We are planning to attack American soldiers. If American civilians get in the way that's their problem." Obviously, over time AlQaeda became more militant. After the interview was over, I thought that was all very interesting. How do you attack the United States from a mud hut in the middle of the night in Afghanistan? And the answer came the year later when they blew up two American embassies almost simultaneously, in Tanzania and Kenya, killing more than 200 people. Which was interesting for three reasons: One, It demonstrated that Al-Qaeda was capable of attacking thousands of us from its space in Afghanistan Two, it demonstrated that they had no compunction about killing as many civilians as possible. There's a very famous formulation about terrorism from the 1970s by Bryan Jenkins, one of the main academics to study terrorism in this country: you want a lot of people watching but not a lot of people dying. Well on 9/11, you had a lot of people dying and a billion people watching. 9/11 was arguably the most viewed event in human history. The reason that previously terrorists didn't want to kill a lot of people, but wanted a lot of people watching, is that killing a lot of people either might dry up your popular support or it might provoke some massive response against you. This was seen in the behavior of the IRA in Ireland. Their largest massacre killed 29 people. Whereas Al-Qaeda, even before 9/11, was demonstrating that they were interested in killing as many people as possible. The other aspect of the attacks in Africa that was especially interesting was that Kenya is a country with 30% Muslim population. The US lost a huge opportunity for propaganda by not framing Bin Laden as somebody who has killed more Muslims than Americans. Twelve Americans died in Kenya in the embassy attacks and 200 other people died, a good number of them were Muslims. The US didn't use that propaganda advantage. President Clinton tried to respond aggressively. He launched cruise missiles at Al-Qaeda training camps, which were more or less ineffective. Bin Laden became more and more convinced that the United States was a paper tiger. Eventually, Bin Laden became more and more convinced that the United States was a paper tiger. In the interview that we did with him, he made the argument that the United States is very similar to the former Soviet Union and their withdrawal from Afghanistan. He based his analysis on the US withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970s, the US pull out from Beirut in 1983 (after the marine barracks attack), and the US pullout overnight in Somalia after the Black Hawk Down incident where eighteen US servicemen were killed. Bin Laden's arguments were based on a naïve view of America. The United States was not going to pull out of the Middle East because we were attacked in Washington or New York. Bin Laden believed that the US was so weak that an attack, on the scale of 9/11, would inflict so much pain on the US that they would pull out of the Middle East. He believed that the Arab regimes he opposed, particularly the Egyptians and the Saudis, would crumble without the US there to support them. Not one part theory made any sense. In fact, a number of the smarter people within Al-Qaeda who weren't ‘yesmen,' argued to Bin Laden that attacking the United States is not such a smart idea. Some of them argued that the attack was actually not in keeping with Islam. They argued that the attack will be bad news for the Taliban, who were hosting them. Bin Laden had even sworn an oath of allegiance to the Taliban, and his advisors warned him that he could be indirectly harming their hosts in Afghanistan. Bin Laden ran Al-Qaeda like a dictatorship. There are many differences between Al-Qaeda and the Nazis. But one similarity that is important is that, when you join Al-Qaeda, you swore a personal oath of allegiance to Bin Laden. When you joined the Nazi party you didn't swear an oath of allegiance to the Nazis, you swore an absolute oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler. Bin Laden made all the decisions, and he ignored all the good internal advice that he got. 9/11 attacks succeeded in their primary objectives. The attacks proved to be Pearl Harbor, in a sense, for Al-Qaeda. Just as Pearl Harbor was a great tactical victory for Imperial Japan, within four years as a result of Pearl Harbor, Imperial Japan ceased to exist. So with 9/11, it looked like a huge victory for Al-Qaeda but in fact it was a disaster. For several reasons: First of all, what does Al-Qaeda mean? Al-Qaeda means "the base" in Arabic. What happened? On October 7th, George W Bush launched an operation with 300 US Special Forces and a hundred CIA officers on the ground in Afghanistan, and won one of the great unconventional victories of the modern era. The US overthrew the Taliban government in three weeks, and Al-Qaeda lost their base in Afghanistan. They have never recovered a similar base. They migrated to Western Pakistan to some degrees in the tribal areas, and they tried to reform a base there, but it was nothing on the scale of the pre-9/11 Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, Al-Qaeda ran a parallel state to the Taliban. They had their own foreign policy; attacking U.S. embassies, warships, and American cities. They had thousands of people graduating from their training camps. They have never revived a similar base of operations. By that standard, 9/11 was a devastating failure for them. In fact, a number of them publically made postfacto rationalizations to say it was a great victory. They claimed that the whole plan all along was diabolically clever to draw the United States into Afghanistan, to bleed us dry economically. There's no evidence for that being the case at all. There was no evidence that they planned for that scenario. That argument provides a very naïve view of the United States, and the size of the American economy. Even though 9/11 was a pretty big economic cost to the United States it cost $500 billion as a general consensus, the US's $13 trillion dollar economy allowed us to shrug it off. You could even make the argument that it was actually, from a Keynesian point of view, very good for the American economy. It's not an accident that 6 out of 10 of the richest counties in the United States are around Washington right now. Wars are very good for the American economy. It was true for World War II, and it was true for Vietnam. Wars tend to be a Keynesian pump. I'm not saying that's a good thing or bad thing, I'm just noticing that Al-Qaeda's economic understanding of the United States didn't make a lot of sense. So Al-Qaeda didn't read us right economically, they weren't trying to bamboozle us into invading Afghanistan in order to replay the Soviet debacle there. Their whole strategy was based on fallacies. Instead of pulling out of the Middle East, the US actually occupied and continues to occupy Afghanistan. We also occupied Iraq for many years. Furthermore, we have created vast American bases in places like Bahrain, and Kuwait, and Qatar. Al-Qaeda's strategy was a failure for both the organization and the larger strategy. The book that I wrote, The Longest War, was written before the death of Bin Laden and before the events of the Arab Spring. I say in the book that Al-Qaeda basically lost the longest war. They lost for several reasons that go beyond what I've just said. They lost the war of ideas in the Muslim world not because the United States won them; as you know, the United States is widely disliked. President Obama himself is hated about as much as President Bush was in the Arab world. I think its mostly because of the Arab-Palestinian issue in which the Obama Administration has not played a principally constructive role, particularly not if you're in the Arab world. President Obama rather eloquently said at one point that Al-Qaeda were small men on the wrong side of history. President Bush also rather eloquently said, 9 days after 9/11 that Al-Qaeda would be, at a certain point, consigned to the graveyard of discarded lies, just as Nazism and Communism had been before. That process was already happening before the Arab spring and the death of Bin Laden because of the four issues I'm going to now mention. One, Al-Qaeda and its allies were killing a lot of Muslim civilians. This wasn't very impressive for a group that positioned itself as if they were the founders of Islam. That argument was undercut by, among other examples, the atrocities Al-Qaeda in Iraq perpetrated during the insurgency. Those acts were very widely covered in the Arab world (particularly by Al Jazeera). [Al-Qaeda] claimed that the whole plan all along was diabolically clever to draw the United States into Afghanistan, to bleed us dry economically. West Point has done a fascinating study of Arab language news accounts of terrorist attacks in the Arab world, and they found that the Arab language news accounts of these terrorist attacks routinely pointed out how many Arabs or Muslims had died in these attacks. It became clear, particularly in the 2006 period when AlQaeda in Iraq was at its absolute worst peak, that Al-Qaeda was beginning to be seen as a group that wasn't defending Muslims. Al-Qaeda was the essential motor that created the civil war in Iraq. Especially because Al-Qaeda was supplying the suicide bombers that were driving the civil war, and that most of the suicide bombers were actually foreigners coming from Libya or Saudi Arabia. We have studied documents to show that those were the two most important countries that were driving the attacks, and they weren't Iraqis they were foreigners. So the fact was that Al-Qaeda was killing many Muslim civilians across the Middle East. For example, in 2005, Al-Qaeda attacked three American hotels in Amman, Jordan, and almost all the victims were Jordanians attending a wedding. Now if you were to construct the absolute worst operation that AlQaeda could come up with, killing a lot of civilians attending a wedding would be that operation. And even the complete psychopath Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was the leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq at the time, had to justify the Amman bombings by saying that the reason they attacked there was because Israeli spies were staying at the hotels. Even he had to do a quasi-apology for this attack. It wasn't just in Jordan and Iraq, Al-Qaeda had started attacking Saudi Arabia. Most of the victims of these attacks were Saudi civilians. The Saudi Government, which had up to that point had a sort of acquiescent approach to Al-Qaeda, then really turned against them. The Saudi population turned against them as well. We also saw that in Indonesia. In 2002 there was the attack in Bali that killed mostly Western tourists at two nightclubs. After that, Al-Qaeda's affiliate in Indonesia went on a spree of terrorist attacks, which killed mostly Indonesians at hotels in Jakarta. Then they went back to Bali in 2005 just as the very important Bali tourism industry was recovering. That was another attack that killed mostly Indonesians. I can give you many other examples but the point is that Al-Qaeda was killing a lot of Muslim civilians, and this was not impressive to most Muslims. The second point as to why AlQaeda lost the war of ideas in the Muslim world was that they had no positive vision. There're a lot of problems in the Arab world that need to be dealt with, and yet Al-Qaeda and Bin Laden never had any ideas of how to fix them. With Bin Laden, you knew what he was against, but what was he for? What did he want to achieve? If you were to ask him, he would say that he wanted the restoration of the Caliphate. By that, he didn't mean the restoration of the Ottoman Empire a relatively rational group of people that treated minorities fairly well he meant Taliban-style theocracies from Indonesia to Morocco. Most Muslims don't want to live under the Taliban. As we see the Arab spring develop, clearly there are some people who would like elements of Talibanstyle theocracy, but it's largely a minority position in most of these countries. Two other quick points on AlQaeda and why they lost the war of ideas: they made a world of enemies, which is never a winning strategy. They kept adding to their list of enemies instead of adding to their list of allies. Eventually AlQaeda was saying that anybody who is Shia can be targeted, or that any Muslim who doesn't precisely share our views can be targeted. For instance, Al-Qaeda in Iraq would kill people for smoking. Or it would kill people who used ice because the Prophet Mohammad didn't use ice in 7th century. These are ridiculous kinds of policies. Al-Qaeda said it's against every middle-eastern government, the U.N., international media, Russia, China, India. There wasn't a category, institution, person, or government that they haven't said they were against. The final point is Al-Qaeda has said, and when I say Al-Qaeda I mean Jihadist militant groups in general, that they will not engage in conventional politics. They will not turn themselves into Hezbollah or Hamas and begin providing quasi-government services. An "Al-Qaeda hospital" is an oxymoron; an "Al-Qaeda school" is an oxymoron. Clearly Hezbollah and Hamas do engage in conventional politics and have a social welfare component. Al-Qaeda and groups like it do not and will not. All that was true before the Arab Spring. What I've found interesting, as a Bin Laden observer, was his silence about the Arab Spring. Why would he be silent when, since 9/11, Bin Laden has released over 30 videotapes and audiotapes? He has commented on any issue of any interest to the Muslim world at large. In 2010, he talked about the catastrophic floods in Pakistan; in 2009 he talked about the Israeli incursion into Gaza; last year he talked about the French banning the wearing of the burka in public; he talked about every issue, but the one thing he didn't talk about was the Arab spring, which is, after all, the most significant event in the middle east since the collapse of the Ottoman empire after World War I, and he had nothing to say about it. Why did he have nothing to say about it? Because here was exactly what he wanted to happen, yet it had nothing to do with his ideals and it had nothing to do with his men. During the Arab Spring, I never saw a single protester holding Bin Laden's picture up, and only a few of the protestors were spouting anti-American rhetoric. In large measure, the United States wasn't really part of their conversation. There wasn't much anti-Israeli rhetoric, in any of these revolutions. It was much more about things that Arabs want for themselves; an accountable government, an independent judiciary, and a free press. These were all demands that anyone in the world would conceivable desire. The demonstrators weren't protesting problems outside the Middle East itself. Bin Laden had nothing to say because he didn't know what to say. Then, all of a sudden, he was killed. As I indicated earlier, Al-Qaeda was a group that he personally founded by Bin Laden. His followers fused him, part and parcel, with the whole group. It is again similar to the Nazis. When Hitler died, Nazism died with him. It's an interesting question, to what extent Bin Ladenism or Al-Qaedism will die with Bin Laden? Or, to what extent it was already dying? His successor, the Egyptian Aymen Al-Zawari, is not the same charismatic leader. He will manage what remains of the group into the ground. The other reason why Bin Laden didn't have much to say about the Arab Spring is that it undercut his two principal ideas. One, change could only come through violence. Of course, in Tunisia and Egypt, the revolutions were largely non-violent. Two, change can only come through attacking the United States. As I've mentioned, the United States really wasn't part of the conversation during the Arab Spring. Now can Al-Qaeda and groups like it try to take advantage of the Arab Spring, and what's going on? In some countries, the answer is yes. Yemen is the one where the most opportunities exist. There were already two civil wars going on in Yemen, before the recent events there: one in the north with the Houthi minority, and one in the south with the secessionists there. Now, there are essentially three civil wars going on. Al-Qaeda tends to thrive in chaotic situations. Especially those where there is a lack of centralized control. Yemen has a serious lack of central government control. It's the poorest country in the Arab world, it is running out of both oil and water, half the population is chewing khat which means that half the population is high after two o'clock in the afternoon, it's very tribal, and it's very mountainous. All this adds up to making Yemen a great place for Al-Qaeda to set up shop. After all, AlQaeda is an Arab organization and so they will try to institute themselves into what is going on in the Arabian Peninsula. Sgt. 1st Class James Tembrock, platoon sergeant of 1st Platoon, fires his M-4 rifle during a firefight with al-Qaida in Iraq operatives near an insurgent safehouse south of Hussein Hamadi village, Diyala province, Iraq, Oct. 29, during Operation Ultra Magnus. Coalition forces killed four AQI members who were using the home as a base of operations to conduct terrorist activities in southern Diyala province. This can already be seen in the group Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which is the outfit that was responsible for the attempt to bring down Northwest Airlines Flight 253 over Detroit. Al-Qaeda groups like it have actually been able to seize territory in parts of Yemen over the past several months. Could Al-Qaeda try to take advantage of what's going on in Syria? I think the answer is maybe. The Director of National Intelligence, James R. Clapper, recently testified and said that Al-Qaeda in Iraq is moving into Syria. They have long used Syria as a place where they could transfer suicide bombers from around the Middle East, so they have connections to Syria. In Libya, I think it's unlikely that AlQaeda, or groups like it, will have much of a role. That said, one of the leaders of the Libyan government is somebody who is a part of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group. The Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, until recently, was an Al-Qaeda related group. They agreed to a peace deal with the Gaddafi Government in which they rejected Al-Qaeda. Could that change? Maybe. Moving now to the Arab Spring, during which Al-Qaeda had little role in, and hopefully will have little role to play in the future. The question is, how will the Arab Spring play out in different countries? Clearly the monarchies are going to survive much better than the dictatorships. They have the option of becoming a constitutional monarchy. The dictatorships cannot become constitutional dictatorships; there is no such thing. This provides a way out for monarchies, who already tend to have more legitimacy. For example, the King of Jordan claims to descend from the Prophet Muhammad, and the King of Morocco claims to descend from the Prophet Muhammad. By the way, I'm not a mathematician, but almost all of us could claim to descend from the Prophet Muhammad. If you think about the math, we are about thirty generations away from the prophet Muhammad, maybe the mathematicians in the room could tell me but I am sure that two to the power of thirty is a very large number. These monarchies claim that since they descend from the Prophet Muhammad they ought to be afforded some measure of legitimacy. The Saudi Arabian monarchy is the defender of the two holy places, it's the third monarchy we now have, and it's been around since the 18th century. The Qatari royal family has been on the throne since 1825. These are established ruling parties. These monarchies also have a significant amount of economic power; they are some of the richest countries, per capita, in the world. Saudi Arabia has the world's largest oil reserves. They can attempt to bribe their populations, using their oil wealth, as a quid pro quo for not having a liberal state. I do think the monarchies will evolve. Kuwait already has a parliament that is somewhat effective. The Al-Sabah royal family has been on the throne in Kuwait since the 18th Century. They are more or less here to stay. Where you will see big change, and have already seen big change, are the dictatorships. Dictatorships tend to not have much oil, they don't have religious authority, and they also haven't been around for very long. If you look at the dictatorships in Yemen, Libya, or Syria, you will see that they are a relatively recent phenomenon. Egypt is a very interesting case. It reminds me a little of Romania. It reminds me a little of Romania. I was in Romania when the revolution happened against Chauchesku. During the Romanian Revolution, the people around Chauchesku realized that it was time for him to go, but they continued to control the government. So Romania didn't really become a representative democracy in the classical sense, it was Chauchesku's circle who retained a lot of the power. Egypt looks a lot like that right now. The military staff and the military high command realized they had to throw Mubarak overboard. With Mubarak gone, they seem to want to preserve their power. Egypt has the tenth largest army in the world, 450,000 soldiers. They are a major part of the Egyptian economy. The army is, in a sense, the regime. So the question in Egypt is, will Egypt become more like Turkey whose strong army checked itself and allowed a moderate Islamist government to develop? Or will they become like Pakistan, where the military retains a total veto over all elements of national security and also controls large chunks of the economy? We do not know the answer to that question. I was very surprised at how well the Islamists did in the parliamentary elections. I thought the Muslim Brotherhood would get thirty percent of the vote, and they got a little bit more than that. I did not predict that the Salafists would get twenty-five percent of the vote. Salafists are ultra-conservative, ultra-fundamentalist Muslims. There is really nothing inherently wrong with that. There is no doctrine in Salafism that says you need to engage in violence, but we will have to see how this develops. Al-Qaeda tends to thrive in chaotic situations. Especially those where there is a lack of centralized control I'm also not terribly perturbed by the Muslim Brotherhood. I've met a lot of leaders in the Muslim Brotherhood, they have always seemed to be quite rational people to me. They tend to be doctors or lawyers. Firmer conclusions will be drawn as Egypt's future becomes clearer will, but we can already say that it does not look good for Israel. Egypt has ended the political blockade in Gaza and an Egyptian mob attacked the Israeli embassy. Furthermore, Israel can no longer make the claim that it is the only democracy in the Middle East which was a frequent claim that it used to justify its special status. As the old regime disappears, and the new regime springs up and more accurately reflect the feelings of the Egyptian population, I think the cold peace between Egypt and Israel might turn into something more hostile. That certainly could be the case if the presidential election gives the Islamists even more control of the government than the seventy percent stake of parliament they have already won. The peace agreement between Egypt and Israel may, in fact, not stand. I have asked people in the Muslim Brotherhood, "what about the peace agreement with Israel?" They have given a rather ambiguous answer, which is that they will observe the truce, but if the population wants us to amend it, then we will change. Another big Loser in all this I think is Iran. They are about to lose their critical Syrian ally. That means that they will not be able to resupply their militia in Lebanon, because there's no overland supply route. They can no longer claim that they are the only revolutionary state in the Middle East since 1979, and I think they will be on the losing side of all this. I think The Arab Spring is probably a net neutral for the United States. The rebelling populations are more anti-American than the dictatorial or authoritarian regimes. We may see a Middle East that is less inclined to go along with what we would like going forward. The final big loser is Al-Qaeda, for the reasons I've already outlined. While the Arab Spring could be a fairly good thing for Al-Qaeda in Yemen, the United States still has a pretty aggressive campaign against them. The United States was able to kill Anwar AlAwlaki, the American cleric in Yemen. It is very interesting that, Obama is the first American President to authorize the assassination of an American citizen. This is just pure speculation on my part, but imagine if George W. Bush had quintupled the number of drone strikes in Pakistan and was authorizing the assassination of American citizens. I think left side of the Democratic Party and the human rights organizations would be making a much bigger fuss about it then they are now. I think Obama has largely been given a pass on this. Part of the reasons for this is that these operations are very secretive, and it is hard to understand the legal authorizations. Attorney General Eric Holder has begun to explain why it is okay for the government to kill American civilians, and I think his explanation can be summarized as: this guy was part of AlQaeda, and Al-Qaeda is at war with the United States. Therefore it does not even matter if he is American, or not, because the Authorization for Use of Military Force, which was in place after 9/11, allows us to attack and kill these people. We are still at a strange point where the authorization of assassinations of American citizens is happening. In fact, Al-Awlaki's sixteen-year-old son was also killed in the drone strike, so now drone strikes are killing American minors overseas. Al-Qaeda in Yemen is under a lot pressure from drone strikes, and from U.S. Special Operations forces that are working there. That said, the bomb maker that tried to get the bomb onto Flight 253 is still out there. He tried to hide bombs in toner cartridges on two American cargo planes flying to Chicago. They were found in Dubai, and the only reason they were found is that the Saudis actually gave the United States the routing numbers of the packages. It was incredibly specific information. This very skilled bomb maker, who can make bombs that can be smuggled onto planes which are virtually undetectable, is still out there. Al-Qaeda in Iraq is experiencing a very predictable resurgence. The fact that we left hasn't hurt them and that they have learned from their mistakes, during the 2006 time period, has been beneficial to them. Whenever there is a very large attack in Baghdad, it is almost certainly Al-Qaeda in Iraq, and they will continue trying to attack the Shi'a government going forward. Lashkar-e-Taiba, who perpetrated the Mumbai attacks in 2008, may well try to attack another major Indian city. That would be a possible prelude between a war between India and Pakistan, two nucleararmed nations. One of Bin Laden's most toxic legacies was to infect other groups with his beliefs. One of those groups is the Pakistani Taliban, which is known by its initials TTP. This manifested itself in Faisal Shahzad, who worked as a financial analyst at the Elizabeth Arden Company in Connecticut before he took up arms on behalf of the Taliban. He is an American citizen who was trained by the Pakistani Taliban, and came back to the United States. Shahzad was living a middle class lifestyle, and was married with kids. He then bought an SUV, drove it to Times Square on May 1st 2010. He checked video footage to determine when the best time to detonate a bomb would be, and found that he could kill the most people by detonating a bomb on Saturday at 6 p.m. One could hardly imagine a better place to inflict maximum damage. Luckily it didn't work, but the Pakistani Taliban have showed some interest in wanting to attack the United States. There are other groups too, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, for example. Also, the Islamic Jihad Union, who have training bases in western Pakistan, and tried to attack Ramstein Air Force Base, in 2007. These groups will continue their efforts. Some of them we will die off. Some will grow as Bin Laden's ideas continue to percolate. Even though he lost the war of ideas in the Muslim world, writ large, there will always be some takers, some a disaffected young man or woman, who will be sympathetic to these ideas not only in the Muslim world but here in the United States. Just think of Major Nidal Hasan, who was influenced by Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and then killed 9 of his fellow soldiers at Fort Hood. So, Going Forward, What Can We Expect the Threat of Terrorism to Be?I am concerned about a second, Mumbai-like, attack. I am concerned about an attack along the lines of the anthrax attack in 2001. A somewhat skilled microbiologist in the Muslim world in Indonesia or Pakistan, motivated by some Al-Qaeda like ideas, could put together an anthrax weapon or something like it. That's not a ‘chicken little' scenario, it is plausible. Future small-scale attacks in the United States are also very plausible, and they will continue to happen. One thing that might be a game changer would be the bringing down of a commercial airliner with a surface-to-air missile or a plastic explosive bomb. That would have a devastating effect on commercial aviation. It wouldn't be a second 9/11 to be a significant attack. Those are the kinds of things that, going forward, people should be concerned about. The threat from terrorism is still very small. I speak as somebody whose expertise is terrorism, so I should naturally try to inflate the threat. You are much more likely to die in the bathtub drowning than to die in a terrorist attack in almost any given year in the United States. Around 300 Americans accidentally drown in their bathtubs, and we do not respond with an irrational fear of bathtub drowning. In the same way, we should not have an irrational fear of terrorism. On 9/11 Al-Qaeda got very lucky, those fifteen people hijackers got very lucky. There was no TSA and there was no Department of Homeland Security. On 9/11, the FBI and CIA were barely talking and there were very few joint terrorism task forces, now there are over 100, including the National Counterterrorism Center. President Barack Obama salutes at Andrews Air Force Base before departing for Columbus, Ohio in March of 2009 The US has put forth a giant amount of resources to the problem of terrorism. When the ship of state turns, it takes awhile, but I think we have the problem more or less covered. It is very hard for a politician to make that kind of statement, because what if your wrong? It is easy for people who are national security experts to say terrorism no longer a national security problem, it is more of a 2nd order threat. We did not treat the Oklahoma City attack where 168 Americans were killed, as an event that required us to revise our entire national security policy. We will see those kinds of attack in the future, maybe not on the scale of Oklahoma City. Terrorism is one of the oldest forms of warfare, and it is exceedingly difficult to stop lone wolves. Timothy McVeigh, the perpetrator of the Oklahoma City attack was not technically a lone wolf, because he had at least one coconspirator, but he was not operating as part of a large group – it's very hard to stop that. Major Nidal Hasan, the Fort Hood shooter, was operating as a lone wolf. Faisal Shahzad was a lone wolf with help from overseas. It does not matter how many resources you put at the problem, you can never eliminate the threat from lone wolves. Think about it, there is no more heavily policed place in the world then Times Square on a Saturday night, but Shahzad still tried to carry out his attack. You can put up all the deterrents you want, but when people are on a mission it's hard to stop them. But I think the threat of terrorism is receding, but you wont hear a politician say it… because what if they're wrong? I wanted to talk a little bit about Pakistan and Afghanistan. Pakistan is a country that is very easy to be negative about, but let me just throw out some positives because you don't hear that so often. Pakistan had an Arab Spring before there was an Arab Spring. They got rid of their military dictator; it was a civil society movement, and the media was very much a part of it. 10 years ago, in Pakistan, there was one TV station, which was essentially government propaganda. My understanding is there are now eightynine TV channels in Pakistan. All of them are very anti-American, but many are very anti-Taliban, and many are pro-democracy. This media diversification and liberalization is a very good thing for Pakistan going forward. Pakistan also has an independent judiciary. The whole dispute that got Nawaz Sharif out of office was he sacked the Chief Justice. Before the Arab Spring was cresting, the Pakistanis rose up and got rid of Sharif. The judiciary has proven itself to be quite independent, both in terms of asking for the ISI military intelligence to produce prisoners who've mysteriously disappeared, and at the same time insisting that cases against President Zardari go forward in a Swiss court. Recently, something very unpredictable happened. Pakistan granted "most favored nation" status to India on trade, which was something that two years ago no one would've thought possible. I think there's a growing sense in Pakistan, where the economy's doing pretty poorly, that if they don't attach themselves to the Indian engine of growth they will be left behind. So the fact that there are growing trade links between Pakistan and India is a very good thing. 2% growth rate is obviously a very big problem for them. Only 2% of their population pays taxes, another big problem. But I think Pakistan will muddle through, it's done so in the past. On Afghanistan, again you know what all the negatives are, but I just wanted to emphasize some positives. I was there under the Taliban, so I have a certain civil war sense of what it looks like over time. Afghanistan, under the Taliban, a doctor ran about $6 a month, which is not a lot of money. The Taliban, obviously, incarcerated half the population in their homes, didn't allow girls go to school, and the economy basically dematerialized. Last year the there was a 10% GDP growth rate, a change from a very low growth rate in Afghanistan under the Taliban. Under them, there were only one million kids in school and there are now eight million; 37% are girls, under the Taliban it was zero. It's very interesting to me: on the left, people really want us to get out of Afghanistan, and I remember, before 9/11, on the left there was a lot of criticism of the Taliban for their despicable treatment of women. I don't really here any discussion on the left right now about what the Taliban resurgence would do to women's rights and girl's rights in Afghanistan, and I think it would be a disaster for them, quite clearly. The Taliban haven't said anything about what their plans are for the country. Not that they control the whole country, but if the right certain set of circumstances happen they will certainly come back to power in parts of the south and east of Afghanistan. Afghans are very optimistic about their future. One of the most common polling questions you can ask is "is your country going in the right direction?" Seven out of ten Afghans think theirs is. That's not true in the United States. If you go back to 2008, I think only 20% of Americans thought the country was going in the right direction, but we were in the middle of this huge recession. So Afghans are positive about the future. Why are they positive? Well they lived through the Soviet Invasion, the civil war, and the Taliban. Any one of those would be pretty bad; in combination, this has really damaged Afghanistan very much. They know, with all the problems that exist, that what is happening is better than the past. If you go to Kabul, there are traffic jams now. Under the Taliban, there was no traffic because there were no cars. It was like driving into Phnom Penh under the Khmer Rouge perhaps. There was no economic activity; there was no phone system, now one in three Afghans has a cellphone. I can count off a whole list of indicators that show Afghanistan is doing better than we think. I think often people think Afghanistan is sort of like Iraq because we have American troops there and it seems to be a very bad situation. In Iraq, when the violence peeked in 2007, you were twenty times more likely to be killed in Iraq than you are to be killed today in Afghanistan. In Iraq, the violence was off the charts. You are still more likely to be killed in Iraq, by the way, today than you are to be killed in Afghanistan. The war in Afghanistan is just not that violent. The administration has put a lot of faith in Taliban negotiations. I think it's a pipe dream. There are some powerful reasons for that. Mullah Omar is not Henry Kissinger. He's not a rational actor. When Omar came to power, he anointed himself as Commander of the Faithful. This is a rarely invoked religious title, dating back to the time of the Prophet Mohammad, suggesting that he's not only the leader of the Taliban, or the leader of all Afghans, but that he's the leader of all Muslims. So he's a delusional religious fanatic, and the history of negotiations with delusional religious fanatics is not impressive. I think that we will find that he's had an opportunity to reject Al-Qaeda; Bin Laden's death should've been the moment to distance himself from Al-Qaeda and he didn't take it. I think we put too much psychic energy into the idea that negotiations with the Taliban are going to yield anything. I think it would be much better if we put our energy and thoughts into the 2014 election in Afghanistan. If that can be a reasonably free and fair election, I think that can be a big signal to the Afghan people. So just one final thought on President Obama. Surely a lot of people who voted for him have been surprised by the fact that he's actually been one of the more aggressive Commanders in Chief that we've ever had. In 2011, we were fighting 6 wars in Muslim countries: Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen. This was the anti-war candidate, and yet he came in and he has waged war. So I think that he's been a surprise, and perhaps he should not have been a surprise. If you go back to 2007, he was roundly criticized for saying that we will do a unilateral action in Pakistan to get Bin Laden. Hilary Clinton, John McCain, and Mitt Romney who accused him of being Dr. Strangelove – decried Obama's stated Pakistan policy at the time. In fact, Obama was serious; he did do a successful unilateral operation. National security turns out to be his strong suit. If you look at polling data, he's at 65% approval on his handling of national security, which is not what people thought he would be. I think that he's been quite unexpected. I think it doesn't fit with the narrative of the Democratic Party being weak on national security. It doesn't fit with the Nobel Peace Prize winning President Obama, and is a case of cognitive dissonance. He quintupled the number of drone strikes in Pakistan, he tripled the number of American troops there, and he said were going to be there from 2009 until 2014. When we leave Afghanistan in 2014, we will leave as many troops in Afghanistan as George W. Bush had there at the end of his eight years. Obama has been very interesting. It's a very different kind of presidency then perhaps many people thought. I think history will record that this has been the president who's been very liberal in his use of special forces in Yemen and Somalia for example; this is a president who's been very liberal in his use of drones; this is a president who amped up our presence in Afghanistan very substantially. I think all those things are not what people thought when they voted for him about three years ago. About the AuthorMr. Bergen is CNN's national security analyst and a fellow at New York University's Center on Law & Security. He has written for many publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vanity Fair, Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, International Herald Tribune, The Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, Rolling Stone, The National Interest, TIME, Newsweek, Washington Monthly, The Nation, Mother Jones, Washington Times, The Times (UK), The Daily Telegraph (UK), and The Guardian (UK). He is a contributing editor at The New Republic and has worked as a correspondent for National Geographic television, Discovery and CNN. He spoke as part of the Mario Einaudi Center's Foreign Policy Distinguished Speaker series. The following is an editied transcription of his lecture. Mr. Bergen is CNN's national security analyst and a fellow at New York University's Center on Law & Security. He has written for many publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vanity Fair, Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, International Herald Tribune, The Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, Rolling Stone, The National Interest, TIME, Newsweek, Washington Monthly, The Nation, Mother Jones, Washington Times, The Times (UK), The Daily Telegraph (UK), and The Guardian (UK). He is a contributing editor at The New Republic and has worked as a correspondent for National Geographic television, Discovery and CNN. He spoke as part of the Mario Einaudi Center's Foreign Policy Distinguished Speaker series. The following is an editied transcription of his lecture. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |