Exploring the Origins of Achievement Goals and Their Impact on Well-Being

By

2018, Vol. 10 No. 12 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

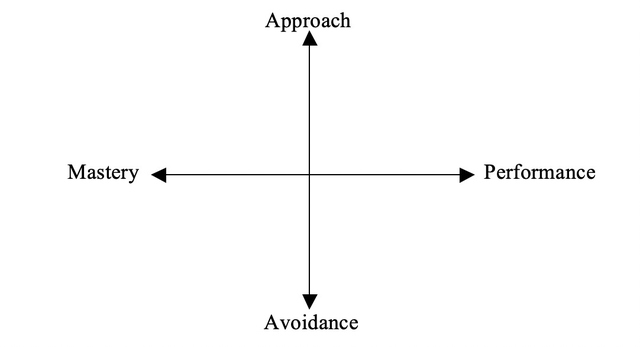

Achievement goals refer to the motivational approach of an individual when facing an achievement situation that challenges the person’s sense of competence, such as a university course (Baranik, Stanley, Bynum, & Lance, 2010; Harackiewicz, Barron, & Elliot, 1998; Reeve, 2009). Research in this area is primarily quantitative and largely does not provide the opportunity for participants to elaborate on why they adopt certain achievement goals or what effect it has on their personal well-being. Drawing upon a questionnaire completed by fifty participants, seven interviews, and three focus groups at a small university in western Canada, this exploratory project intended to answer the following two research questions. First, what underlying factors help to explain why an individual adopts certain achievement goals on academic tasks in a university context? More specifically, what experiences and beliefs influence some people to evaluate their academic competence based on personal development and others to evaluate their academic competence relative to the performance of others? Related, what experiences and beliefs influence some people to focus on approaching academic success and others to avoid academic failure. For example, what role does a student’s family or professors play in the achievement goal they adopt? Second, what are the impacts on personal well-being for each of these achievement goals, relative to a university context? This study adopted the definition of well-being put forward by Dodge, Daly, Huyton, and Sanders (2012): “the balance point between an individual’s resource pool and the challenges faced” (p. 230). Literature ReviewAchievement goals refer to the motivational approach of an individual when facing a situation that challenges the person’s sense of competence (Barron, & Elliot, 1998). Two categories of achievement goals emerged during the early years of achievement goal research: performance and mastery goals. People who espoused a performance goal were primarily concerned with demonstrating or proving their competence to others, whereas those who adopted a mastery goal were more interested in developing their sense of competence (Dweck & Legget, 1988; Elliot, 2005). Following the mastery-performance distinction, the next major development in the achievement goal research was the inclusion of the approach-avoidance dichotomy. Approach motivation refers to behaviour that is energized by the possibility of a positive or desirable result, while avoidance motivation refers to behaviour that is energized by the possibility of a negative or undesirable result (Elliot, 1999). Elliot and Church (1997) proposed a new, trichotomous framework for achievement goals: mastery, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance. People with a performance-avoidance goal were driven by a desire to avoid looking incompetent in the eyes of others. A few years later, Elliot and McGregor (2001) applied the same partition to the mastery goal, creating the 2 x 2 framework.The distinctive feature of the 2 x 2 framework was the creation of a fourth goal, mastery-avoidance. With this new construct, competence was still defined intrapersonally. That is, competence was measured by personal development. The avoidance dimension of this goal related to the individual’s motivation to avoid feeling incompetent. Elliot and McGregor cited practical examples of this goal orientation, including “striving to avoid misunderstanding or failing to learn course material” and “striving not to forget what one has learned” (2001, p. 502). For example, university students, who are perfectionists, fit the mastery-avoidance goal well because they are often self-motivated to avoid doing anything incorrectly or making any errors. In their study, Elliot and McGregor (2001) utilized explanatory and concept factor analyses to demonstrate that the four proposed achievement goals were distinct constructs, and that the 2 x 2 framework was a more useful explanatory tool than the trichotomous model and other alternatives previously discussed. Since its inception, Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) 2 x 2 framework has been tested and confirmed as a valid model. In their meta-analysis of the mastery-avoidance goal, Baranik et al. (2010) found that it was both a conceptually and empirically distinct construct and should be included in the achievement goal framework of future studies. It has been widely accepted and utilized by researchers in the field (Alkharusi, 2010; Baranik et al., 2010; Lieberman & Remedios, 2007). A final, but significant aspect of the 2 x 2 framework is that the four goals should not be conceptualized as isolated constructs. Elliot and McGregor (2001) commented that there was a degree of overlap between certain achievement goals; a goal would have commonalities with other goals that shared a competence dimension (i.e., definition or valence). Origins and Impacts of Achievement GoalsAn exploration of the literature revealed that underlying achievement goals derived from various origins: self-theories, broader motivational dispositions, intrinsic vs. extrinsic/internalized motivations, self-determination theory, expectancy value theory, and relationships with instructors, parents, and peers. One of these antecedents is self-theories, which refer to what individuals believe about themselves (Dweck & Legget, 1988). More specifically, research has focused on the effects of whether an individual believes his or her personal intelligence is fluid (i.e., incremental theory of intelligence) or fixed (i.e., entity theory of intelligence) (Reeve, 2009). Dweck and Molden (2005) discovered that students who subscribed to an incremental theory of intelligence, or that intelligence can be improved, tended to hold strong mastery goals. Conversely, Elliot and McGregor (2001) discovered that students who adopted mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance goals were more likely to believe that their level of intelligence could not be changed. These differences hinge upon the meaning of effort. If a student holds the view that his or her intelligence is changeable or fluid, he or she must simply exert the necessary effort in order to master the task at hand. On the contrary, for students who believe that intelligence is fixed, “high effort means that the performer lacks ability” (Reeve, 2009, p. 191). These individuals may adopt performance goals in order to prove their skills and abilities to others. With regard to the mastery-performance distinction, three theories are often discussed in the literature: intrinsic motivation vs. extrinsic/internalized motivation, self-determination theory, and expectancy-value theory (Baranik et al., 2010; Ormrod, 2012; Reeve, 2009; Schunk & Pajares, 2005, Urdan & Turner, 2005). A high degree of interest in the task at hand is a good predictor of mastery goals, particularly mastery-approach. Extrinsic motivations, or drives that originate from sources outside the individual, and internalized motivation, or the adoption of others’ values, are more often linked to performance goals than to mastery goals (Ormrod, 2012; Reeve, 2009). Self-determination, or the individual’s desire for choice and autonomy, is also a good predictor of mastery-approach goals. While self-determination is relatively unrelated to performance-approach goals, it is negatively correlated with both of the avoidance-oriented constructs. Expectancy-value theory explains individual motivation with two variables. On one hand, the person must have a high expectation (i.e., high self-efficacy beliefs) to succeed. On the other hand, the individual must also see some form of benefit in the task. The individual’s environment and relationships also play a significant role in the adoption of certain achievement goals. Ames (1992) found that students were more likely to adopt mastery goals when they were given a measure of control and choice over their learning, evaluations were made privately and focused on individual progress, and tasks were diverse and offered an appropriate level of challenge. Conversely, research demonstrated that performance goals were likely to emerge when competing for good grades became a primary focus in the classroom, evaluation was harsh, and instructors openly expressed which students were excelling by displaying their work (Church, Elliot, & Gable, 2001; Lieberman & Remedios, 2007). Outside of the classroom, parents also impact how students approach achievement (Pomerantz, Grolnick, & Price, 2005; Wentzel, 2005). Elliot and McGregor (2001) found that students who adopted mastery-avoidance or performance-avoidance goals were more likely to have parents who expressed person-focused negative feedback and instilled in their children a sense of worry over making mistakes. These researchers reported that students with performance-approach goals were more likely to have parents who expressed conditional approval towards their children and were person-focused in their feedback rather than directing their comments to the child’s specific behaviours. Parenting practices were not only linked to the student’s goal, but also to their well-being. Elliot and McGregor (2001) found that students who received person-focused feedback were more likely to experience stronger anxiety. Arnett (2010) highlighted that an authoritarian parenting style (i.e., highly demanding, low responsiveness) was associated with more negative outcomes on well-being, such as low self-assuredness and social adeptness, than an authoritative parenting style (i.e., highly demanding, high responsiveness). A final aspect of the literature to consider is the impacts of the four achievement goal orientations, most notably the student’s performance and engagement in the classroom. Students who adopted performance-approach goals were more likely to attain good grades but tended not to develop a greater interest in the material being learned (Elliot & Church, 1997; Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, Carter, & Elliot, 2000). Performance-approach goals positively predicted good performance on multiple choice and essay questions on exams, while performance-avoidance goals had the reverse outcome (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). Interestingly, both the mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance goals were only weakly linked to performance. Unlike the performance goals, the mastery-approach goal generally led to subsequent interest in the topic being learned. The mastery-approach goal was also linked to a host of optimal learning outcomes, such as more self-regulated behaviour, persisting in the face of difficulty and even failure, and displaying deep levels of information-processing (Baranik et al., 2010; Ormond 2012). On the other hand, performance-avoidance goals were related to more negative learning outcomes, including severe test anxiety, refraining from asking for help, using superficial learning strategies (e.g., rote memorization), and low persistence in the face of challenging tasks (Ormond, 2012; Reeve, 2009). The learning outcomes for performance-approach and mastery-avoidance goals fell between these two extremes. In contrast to the robust findings on performance and engagement outcomes, the body of research focused on the outcome of personal well-being is not as substantial. Elliot and Sheldon (1997) found that the negative impacts of avoidance achievement motivation went beyond the classroom. The study found that students with this orientation towards school experienced decreased levels of “self-esteem, personal control, vitality, and life satisfaction” (Elliot & Sheldon, 1997, p. 180). Other research linked performance-avoidance goals with increased rates of chronic depression (Ormond, 2012). Conversely, mastery-approach goals were believed to produce positive patterns of emotion and cognition, such as high self-esteem and self-efficacy (Reeve, 2009). In part, these findings are explained by the intrinsic motivation theory: mastery-approach goals facilitated intrinsic interest, which in turn produced a sense of enjoyment in the task (Bergin, 1995). Once again, the four achievement goals were viewed in a hierarchical fashion. Mastery-approach was portrayed as the most beneficial to well-being, while performance-avoidance was viewed as the most detrimental. Performance-approach and mastery-avoidance fell somewhere in between. This limited amount of data points to the need for more research that would explore the impacts of the four achievement goals on personal well-being. Dodge et al. (2012) noted that a serious problem with research in this area was the lack of an operational definition for well-being. To address this, Dodge et al. (2012) proposed the following definition to serve as a basis for measuring well-being: “the balance point between an individual’s resource pool and the challenges faced” (p. 230). Drawing upon Kloep, Hendry and Saunders’ (2009) work on human development, Dodge et al. (2012) explained challenges as cognitive, social, emotional, material, environmental, or physical stressors that emerge in an individual’s life. In the context of this present study, an example of a challenge could be a student’s desire to live up to their parents’ high expectations. Resources were interpreted by Dodge as the individual’s potential to cope with challenges that come from cognitive, social, emotional, material, environmental, or physical sources. For example, in this study a resource might be a student’s strong reading and comprehension skills that allow him or her to effectively navigate difficult course material. For the purposes of this study, I adopted Dodge’s definitions of challenges and resources to measure well-being. The definition’s emphasis on a state of equilibrium is strongly rooted in Csikszentmihalyi’s flow research (as cited in Reeve, 2009). As Csikszentmihalyi demonstrated, a strong sense of enjoyment and deep involvement arises from optimal challenge, a condition where moderately high or high task difficulty is matched by an individual’s equally high level of skills and resources. When task difficulty outweighs personal resource, competence is threatened and people experience worry (moderately over-challenged) or anxiety (highly over-challenged). On the other end of the spectrum, being under-challenged neglects the individual’s sense of competence, resulting in boredom. Lastly, low skill coupled with low challenge leads to the individual being apathetic towards the task at hand, which Reeves (2009) described as “the worst profile” where “literally all measures of emotion, motivation, and cognition are at their lowest levels” (p. 157). In accordance with this research, Dodge et al. (2012) proposed that personal well-being is only achieved when an individual possesses sufficient resources to respond to a challenge and vice versa. To conclude this literature review, it is important to note that the majority of the studies in the achievement goal literature were primarily quantitative, relying heavily, or exclusively, on closed-ended survey data. Most of this research did not provide the opportunity for participants to elaborate on why they adopted certain achievement goals or to relate important personal experiences and beliefs. Additionally, the outcome of achievement goals that tended to be of central importance in the literature was graded performance. The impact of the individual’s subjective well-being was often given secondary importance. In order to address these gaps in the literature, this present study drew upon focus groups and interviews that qualitatively explored the underlying influences of the four achievement goals that were addressed in the literature (family, instructor, locus of control, personal motivations), as well as new factors that emerged (mature student status, culture, prior home-school experience). Additionally, this study assessed the impact of achievement goals on personal well-being by examining the resources (e.g., supportive family) and challenges (e.g., frustration with required classes) of participants. To evaluate personal well-being, this research sought out indicators of balance or imbalance between each group’s resources and challenges (e.g., enjoyment/deep involvement, worry/anxiety, boredom, or apathy). The Current StudyDrawing upon a questionnaire completed by fifty participants, seven interviews, and three focus groups at a small university in western Canada, this exploratory project intended to answer the following two research questions. First, what underlying factors help to explain why an individual adopts certain achievement goals towards academic tasks in a university context? More specifically, what experiences and beliefs influence some people to evaluate their academic competence based on personal development and others to evaluate their academic competence relative to the performance of others? Related, what experiences and beliefs influence some people to focus on approaching academic success and others to avoid academic failure. For example, what role does a student’s family or professors play in the achievement goal they adopt? Second, what is the impact on personal well-being for each of these achievement goals, relative to a university context? The online questionnaire was a combination of four demographic questions and Elliot and Murayama’s (2008) twelve question instrument, Achievement Goal Questionnaire - Revised (AGQ-R). The primary purpose of this questionnaire was to recruit and sort participants into each of the four achievement categories for later focus groups and interviews. At the conclusion of the survey, participants could sign up for an interview and/or a focus group. Fifty students filled out the questionnaire. Consistent with the fact that more women than men attend the institution where the study was conducted, the sample consisted mostly of female students, comprising 72% of all respondents, or 34 participants. There were 13 male students, or 28% of the sample, who filled out the questionnaire. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 25 and over, with 20 and 21–year-olds each representing the largest age group at nine students (19%). The majority of the sample was in their second or third year of study, with 18 (38%) and 14 (30%) students, respectively. After securing a sufficient number of participants who volunteered following the survey, the next phase utilized focus groups. Due to a shortage of mastery-avoidance participants (an important finding discussed below), focus groups were only conducted for the remaining three achievement goal categories. Four students participated in the mastery-approach group: three male students and one female student. Four students participated in the performance-approach group: two female students and two male students. Two male students participated in the performance-avoidance focus group. All focus groups were conducted at the university. The average length of these focus groups was fifty-four minutes. The final step for this project was the in-depth interview. Seven participants were interviewed. For each achievement goal category, one male and one female student were interviewed. The exception was that only one participant was interviewed for the mastery-avoidance category. All interviews were conducted at the university. The average length of these interviews was fifty-one minutes. After collecting the data, transcripts were created from the interview recordings and extensive notes were taken during the focus group. To analyze the data, this study utilized a grounded theory approach. In response to the first research question, this study coded for important theories and concepts out of the literature, including locus of control, family influence, the impact of professors, and the role of personal motivations. However, this analysis also left room for new, unexpected themes to emerge, such as the impact of being a mature-student or of being home-schooled. With regard to the impact of each achievement goal on personal well-being, this study coded for themes of student challenges and resources. Finally, the data was analyzed for indicators of balance between resources and challenges (e.g., enjoyment) or imbalance (e.g., anxiety, boredom). ResultsThe intent of this study was to explore the following questions: What underlying factors help to explain why an individual adopts certain achievement goals on academic tasks in a university context? Additionally, what is the impact on personal well-being for each of these achievement goals, relative to a university context? This results section begins with a brief summary of the survey data. In order to facilitate comparisons across the four achievement goals, each group is presented on its own. To address the first question, this section examines the four underlying influences on achievement goals drawn from the literature: locus of control, family, professors, and personal motivations. In addition, unexpected themes (e.g., mature student status) that emerged are also discussed. In response to the second question, the most prevalent resources and challenges for each group are presented. Next, the personal well-being section for each group is examined, highlighting indicators of balance (e.g., enjoyment) or imbalance (e.g., boredom, anxiety) between resources and challenges. Finally, findings regarding achievement goal identification across all four groups are discussed. Questionnaire DataThe AGQ-R portion of the questionnaire displayed that the mastery-approach goal was the most common, with eighteen students (38%). The second most common was the performance-approach goal, with ten students (21%). The performance-avoidance goal ranked third, with five students (11%). Only one participant (2%) indicated that he espoused a mastery-avoidance goal. Interestingly, thirteen students (28%) responded to having a multiple goal approach, where two or three of the goal categories were scored as equally influential. It is important to note that of the fifteen students with a multiple goal response, five individuals ranked mastery-avoidance as one of their dominant goals, which may partially explain why the mastery-approach group was so small. 1. Performance-Avoidance GoalThree individuals with a performance-avoidance goal participated in the qualitative portion of the project. As a reminder, the performance-avoidance goal is characterized by “seeking to avoid performing poorly compared to others or embarrassing oneself in front of other students or professors” (Reeve, 2009, 184). Underlying influences.Locus of control.One of the important factors that influenced the participants’ achievement goal was their locus of control. While one student expressed that doing well was mostly in his control, the other two provided a more mixed response. One of these students remarked that “how any student performs is at least partially under their control.” However, he later commented, “there are some professors who I now feel that if I take another course from them, I just will do badly and there’s nothing I can do about that.” Similarly, the other student commented that doing well was in her control “to a certain extent.” When asked why she adopted that belief, this student expressed her views that the testing methods of only some of her professors were fair. Additionally, she voiced her frustration over peer editing and the importance of the technical rules of different writing styles, like American Psychological Association (APA). Recalling a recent assignment mark where she received significant deductions due to citation errors, she expressed her belief that most students who struggle with formatting rely on peer editors to correct those mistakes, which she viewed as a dishonest practice because it is no longer the writer’s own work. Thus, she believed that if she wanted to attain a good grade in certain courses, she could not simply rely on her own ability. Family.The views and influence of the family were an important underlying factor for two of the three participants. The Behavioural Science (BHS) student noted that her parents both valued education, and that her father had attained a bachelor’s degree. However, she commented that when it came to her university education, she was “never, kind of pushed, or encouraged or supported” by her parents. Overall, she did not credit her family or upbringing with having a significant impact on her achievement goal orientation. Conversely, both of the male participants commented that their motivational approach to their education was heavily influenced by how they were raised. Coming from an academic family, one of these participants recounted that while his parents initially had encouraged him to pursue an 80% average as a middle school student, “it very quickly transitioned to “Oh, well that’s good, but you can probably do better.” After identifying himself as a student with a performance-avoidance goal, this individual explained his reasoning:

The other male participant’s reflections aligned closely with this description. He commented:

For both of these very externally motivated individuals, a great deal of the pressure to avoid performing poorly originated from their parents. Professors.All three participants indicated that their motivations were dependent on the professor who was teaching the class. More specifically, each of the three students indicated that their achievement goal orientation varied from instructor to instructor. For instance, one student recounted how one of his recent classes had been largely discussion based. Even with his anxiety over public speaking, the conversation was so engaging that “I wanted to learn extra things so I can bring more into the discussion next week.” He contrasted that with another class where he was more motivated to get through the course with minimal effort because “it’s a professor standing there lecturing and, you know, tabbing through PowerPoint slides.” Another participant noted that she cared a lot more about pleasing professors who respected and invested into their students. Conversely, she shared that she was less inclined to perform well in the classes of instructors who “don’t respect my time.” She related that she has a very hectic schedule outside of school. Thus, she communicated her frustration with professors whose classes run late. Finally, the third participant highlighted that his goal was highly dependent on his relationship with the professor. In large classes in which he was just another face in the crowd, he expressed that he was more oriented towards a mastery-avoidance goal of avoiding personal incompetence. However, in classes where the instructor knew him well, he was motivated to impress the professor and avoid performing poorly in his or her eyes. Personal motivations.Two of the three participants indicated that in all spheres of life, they had a deep-seated aversion to competitive environments. In academic settings and even in leisure activities, such as a game of Monopoly, one participant commented: “I really try to stay away from competition. I can’t do it healthily. I love it if we can all succeed and we’re all happy.” Another participant expressed similar sentiments. When asked about the personal effects of academic competition, he remarked, “I find it very intimidating to go head-to-head with someone . . . if I feel there’s a direct competition, I’m more likely to just kind of try and get by, give the other person an easy win.” In the focus group, this individual’s comments regarding competition spoke to his use of a self-handicapping strategy. He said:

A Business major in this group offered a very different stance on competition. Unlike the motivations of the other two, this individual stated that he had a strong competitive side that extended to various aspects of life, such as sports and academics. He noted that while he did strive to achieve better grades than others, the stronger motivation was to avoid falling behind. Concerning personal growth, two of the three participants expressed that it had little to no effect on their academic motivation. The third participant mentioned that the desire to grow and develop in other areas of life was strong and had spilled over into her academic life to a limited extent. Effects on personal well-being.Resources.All three participants discussed instructors and classroom experiences that were beneficial. They all related that the close relationships that they developed with professors at the university and instructors who taught them earlier in life had a profoundly positive effect on them as students. One individual mentioned that it was an elementary school librarian who had the most positive impact on his approach to learning. He credited her patience with students and her passion for teaching for instilling in him a love for reading, which remains with him today. One student related that it was the insight and encouragement of a professor who opened her eyes to the possibility of going to graduate school and becoming a professional. Another participant, who struggled with severe anxiety over public speaking, recounted one of the assignments that he was the most proud of over his time at the university, an in-class presentation. By taking the professor’s advice and comments to heart, he got the highest mark in the class on the assignment and learned “I can definitely overcome any inabilities or inhibitions I might have.” In addition to the support of instructors, two students related a sense of self-confidence in their own skills and abilities. One student expressed that because she is a naturally outgoing person, she feels well-equipped to give presentations and contribute to class discussions. In addition, she discussed that her love of language has developed into strong reading and writing abilities. Another participant expressed that his strong reading and comprehension skills have been a valuable asset in his studies. Unlike the other two participants, the third student did not mention personal academic strengths. Instead, he was the only individual in the group who believed if he put in the proper effort, he could succeed in any professor’s class. Lastly, two participants shared that the support and encouragement that they received from peers and coworkers had been valuable resources. One of the participants explained that she worked for many years at a summer camp for foster children, and that the affirmation she received from a colleague has remained with her:

The other participant, a student who lived in the university dorms, shared that his “favourite part about [the university] is the community in residence where I’m staying. Just a fantastic group of people.” Not only did he value the friendships with other residence students, but he explained that living on campus has provided opportunities to develop his academic abilities. For example, he explained that speaking at different residence meetings and events has helped with his fear of public speaking. Challenges.While the close relationships with professors had a beneficial impact on personal well-being, they also had detrimental effects. As students with ‘other-focused’ rather than ‘self-focused’ goals, they communicated that professors often became figures in their life who they did not want to disappoint. One participant shared that those professors whom he “knows well” and “are invested in [him] . . . are kind of like parents in a way.” He continued on to share that just like his parents, these instructors were individuals whom he tried to impress and seek approval from. Likewise, another student, a self-professed “people pleaser,” talked about how, over the course of her academic career, she “really wanted to please [her] teachers . . . wanted [her] teachers to like [her], and really wanted them to be pleased with [her].” After recounting the story of a very disappointing final exam mark, she discussed how much the grade negatively affected her relationship with the professor. She related that she “felt so betrayed” and, half-jokingly, remarked that she and the professors were “no longer friends.” For two of the participants, the pressure to please their parents was a major challenge. In the focus group, both participants resonated with the observation that one of them offered on why the fear of failure outweighed the pursuit of success:

A similar view was also shared in an interview, when the student remarked, “When you can succeed, it’s nice; but it’s never as rewarding as failure is punishing.” Another challenge that was discussed by all three participants was the view that education was an undesirable, but necessary stepping stone to a good job. Each of these students expressed that their decisions to attend university and what program to major in were heavily influenced by a societal script that a post-secondary education is the expected transition between leaving high school and entering the workforce. Only one participant talked about how her personal skills and interests played a meaningful role in choosing a university program. One participant stated, “I just really want to get my hands dirty, as soon as I have the opportunity to do that. I am going to do the minimal amount of education possible.” This sentiment was shared by the other two individuals. While they shared examples of classes that they thoroughly enjoyed, this group did not embrace education as an end in itself. Instead, their four-year degree was an arduous means to a desirable job. Indicators of personal well-being.The negative influence of this goal on the participants’ personal well-being was apparent in their sentiments of anxiety and apathy. The same male student who expressed the significant parental pressure to succeed academically (see quotation on p. 17), discussed that once he moved out of his parents’ house, his main source of motivation disappeared. In this new environment that was devoid of external motivation, he became fairly apathetic towards his studies, and his goal transformed into just getting through his university classes. Later, this student talked about how he was often perceived by his peers as intelligent, but also as lazy with a poor work ethic. Even though he did not dispute that he was deserving of this label, he talked about how he disliked being known as lazy. Unlike this individual, the other male participant with parental pressure still lived at home. Because of his daily interactions with his parents, he communicated that worry of disappointing them was fairly constant. Finally, the third participant communicated that “I’m just in a constant state of feeling overwhelmed.” As a student who worked full-time to support herself, she explained that the many stressors that she faces far outweighed her resources. 2. Mastery-Avoidance GoalOf the forty-seven students who took part in the survey, only one individual indicated that he espoused a mastery-avoidance goal, and he was willing to take part in an interview. As a reminder, the mastery-avoidance goal is characterized by “avoiding personal incompetence, avoiding doing anything incorrectly, and fearing that one might not reach their potential” (Elliot & McGregor, 2001, p. 501). Underlying influences.Locus of control.This individual demonstrated a high internal locus of control. He adopted a fluid view of intelligence based on his experiences at university. He explained, “I do feel like if I’m able to spend a lot of time dedicated to a concept or a subject, I feel like I can grasp it at the end.” When asked to recall an exam or an assignment mark that pleased him, he talked about a difficult course that he had taken where he had struggled with the first exam. Rather than credit the poor mark to his academic ability, he attributed the grade to tough material that simply required more effort and attention. By changing his study habits, he achieved a grade that he was proud of on a midterm. While he acknowledged that he sometimes struggled with courses from other disciplines, he did not fault the professor’s personality or teaching style for a lower grade. Instead, he viewed these classes as important, but not as crucial as his BHS classes. Therefore, for courses outside of his area of specialization, he adjusted his standards for what he believed was a good grade. Family.The participant’s family and upbringing affected his achievement goal orientation. Because his parents had limited opportunities for success themselves, they heavily emphasized the value of education as an avenue for success in the rest of life. If he did not finish at the top of his class, he felt as though he had fallen short of his parents’ expectations and disappointed them. Additionally, he expressed how the academic competition between his two academically gifted siblings was another source of pressure. He noted that “during the times where I struggled, that was tough because I was always labeled and compared to my brother.” Professors.This individual credited his professors at the university with fostering his mastery orientation towards his education. When asked to talk about an instructor who had positively impacted his motivational approach to school, he immediately responded with the advice a professor had given him:

He said that this professor, as well as most other professors at the school, had played a major role in shifting his focus towards personal growth and appreciating the subject matter that he studied. Personal motivations.The participant’s personal motivations concerning growth and competition yielded some surprising results. As expected from someone with a mastery-oriented goal, the participant noted that he had always had a love and passion for learning and developing as an individual. Outside of the classroom, he discussed spending his leisure time reading, watching documentaries, and learning new and interesting things about the world. In our discussion, he commented that personal growth was “a really strong motivator” in the classroom, and that he largely measured academic success by how much understanding and appreciation he had gained for the subject at hand. Interestingly, academic competition and comparison was also a strong motivator for this individual. Although he was not a competitive person in other parts of his life, like athletics, he considered academic competition to be “a great thing” that “challenges me . . . forces me to push harder, and . . . benefits me in everything, like the way I study . . . the way I write papers.” He reconciled these differences by highlighting that there was a greater weight to the consequences and implications that his academic work would have on his life after university. Mature student experience.An unexpected theme that continually emerged in the conversation was the impact of being a mature student. This individual had previously attended a larger western Canadian university and had also spent some time in the workforce. From the outset of the interview, he emphasized the importance of his stage of life:

He recounted that because he left a good job in order to return to school, he did not make the decision to return to school lightly. Instead, the success that he experienced in his career fueled his focus to be successful in school. Additionally, he remarked that his previous university experience informed his current approach to school. This individual commented that because he “didn’t achieve the grades that [he] wanted” and “struggled with the course material” at his previous institution, his current university experience was his second chance for academic success. Effects on personal well-being.Resources.In terms of resources, the participant discussed how personally rewarding it was to study an area of interest. He genuinely enjoyed the content, coursework, and teaching within the BHS program. In our conversation together, he stated that his favourite facet of the program had been the opportunity to write research papers on topics of personal interest in nearly every class. He commented, “Now coming to [the university], realizing that this is kind of something that I want to do . . . it definitely makes me more motivated and more excited for the things I’m doing here.” With regards to his professors, this student commented that “all the teaching I get here is great, regardless of the course.” Even beyond the classroom, he noted that his interactions with his professors had been enriching and encouraging experiences. As highlighted earlier (see p. 26), the individual expressed that certain professors had been very supportive during his time at the university, and that their encouragement and insight helped to ease the pressure and anxiety of returning to school a second time. Another resource that this student discussed was the experience of being a mature student. Over the course of his interview, he talked about the benefits he currently enjoys because of his prior involvement in postsecondary education. He commented, “Having that past experience at [a large university], that’s definitely motivated me here at [the university]. I kind of view that as my second shot. And not to drop back into those old habits.” During the gap between his first and second stints at university, this participant enjoyed success in the workforce. He communicated that he applies the same mentality that led to occupational success to his schoolwork. Lastly, the mastery-avoidance participant’s view of intelligence and locus of control served as a resource in his coursework. During his interview, he repeatedly emphasized the necessity of a strong work ethic for academic success. When asked about his conception of intelligence, he responded:

Later, he recounted the story of receiving a disappointing mark on a midterm. Rather than feeling defeated, this individual instead rearranged his priorities, altered his study strategies, and subsequently received an A on the next exam. Challenges.Much like the performance-avoidance participants, this individual highlighted the challenges of living up to the expectations of professors and parents. He discussed how the close relationships with professors at a smaller institution was a challenge to personal well-being. Unlike his previous experiences at a larger university where he could blend in as just another face in the crowd, he felt an increased pressure to live up to the expectations and impress a professor who “knows me by name, sees me every day, and can associate a grade to me.” Even though he realized that his instructors likely did not think in such a manner, he expressed that “there’s that motivation to keep up and not fall back because if I fall back or do poorly, then [the professor] will view me in a negative light.” Additionally, this student felt the pressure to impress his “very competitive family.” Even years removed from living with his parents, he described the “pressure to do just as well or better than his brother” and to be viewed as a success by his parents as enduring challenges. Beyond the pressure to live up to the expectations of others, the participant also related the strong effects that the fear of performing poorly has on him. He commented, “I would feel devastated if I received a C on . . . on anything. Even a B minus, that’s pushing it.” Not only was he concerned with losing face in front of professors and family, but he expressed worry over the “consequences and implications” a bad grade might have on his future career choices. Another challenge that this participant discussed was the difficulty of the liberal arts nature of his university degree. While he talked at length about how much he enjoyed his BHS classes, this individual considered the required classes outside of his major to be stressful and challenging. As highlighted below, frustration and struggle with courses outside of the individual’s discipline was a challenge mentioned by all but the performance-avoidance group. Lastly, the participant discussed the stressor of comparing his performance with other peers. However, unlike the perceived expectations of family and professors, this student strongly embraced the idea of comparing test scores and assignment marks with others. Unlike the majority of performance-avoidance participants, who viewed competition as detrimental and damaging to self-esteem, this individual commented that “when I see somebody that’s more successful than I am, it helps me bring up my level.” For this participant, comparison was not a stressor that weighed him down, but a challenge that prodded him to elevate his effort. Indicators of personal well-being.It was difficult to assess this participant’s general sense of well-being. On one hand, some of his responses indicated that his pool of resources was fairly balanced with the academic challenges he faced. For example, he shared:

He constantly reiterated the idea that “I’ve really had to apply myself a lot more to my studies until I finally get it,” which indicates a fairly even balance of high task difficulty and high competence. His comments that he enjoyed his BHS classes also pointed to a sense of balance. However, the participant remarked, “I definitely do identify more with the fear of failure.” This student shared that he experienced a great deal of “anxiety and fear” when he first came to the university. When asked why that was the case, he explained, “I felt like there was a huge pressure on me to do well, to impress these people that I’ve never met and to show that I could compete with a lot of eighteen-year-old kids.” Throughout the interview, he continually returned to the idea that the consequences of performing poorly were often at the forefront of his mind. Based on these comments, the challenges and pressures of his academic experience appeared to outweigh his resources. Thus, this participant seemed to oscillate between states of balanced well-being and anxiety. 3. Performance-Approach GoalThere were five participants with performance-approach goals: a female student who participated in an interview, a male student who participated in both an interview and the focus group, and two female students and a male student who participated in the focus group. As a reminder, the performance-approach goal is “characterized by seeking to demonstrate or prove competence to others, to display high ability, and to outperform others” (Reeve, 2009, p. 184). Underlying influences.Locus of control.Concerning locus of control, all five participants shared beliefs that doing well in school was in their hands. It was interesting to note that there was not unanimous agreement on the nature of intelligence, with one individual disagreeing with the idea of intelligence as fluid. Rather, she expressed that intelligence is something that you are born with and cannot change. Another interesting finding was that four participants discussed their belief in the personal limitations of students. For instance, one student described that her brother struggled with a learning disability and that he rarely achieved grades higher than a C. Another student noted, “I think some people are capable of getting a ninety percent, and that’s their best. And I think some people are capable of getting a seventy percent, and that’s their best.” With regard to whether doing well academically was in their control, all five participants strongly believed that it was. One student remarked, “I think it’s my pet peeve when people are like, “My prof is awful. It’s his or her fault that I’m going to fail this class.” Four students expressed that the classroom environment and the professor’s teaching style had a marginal effect on their success in the course. However, all five participants stated that personal effort and initiative were the key components to doing well in school. Reinforcing this point, one focus group participant commented:

This sentiment was shared by all of the focus group participants. Family.All of the performance-approach participants stated that family had an impact on their achievement goal orientation. One student communicated that meeting the high academic expectations of her parents was a strong motivator. In her household, school was the top priority. Another participant communicated that she strived to please her parents with her academic performance and follow in their footsteps of academic success. However, she did not communicate that it was a burdensome or overwhelming pressure. Rather, she mentioned that while they emphasized achieving excellence, they also steered her away from defining herself by her grades. For the other three participants, parental influence took the form of support rather than pressure. All three students discussed how their parents encouraged them to do their best and follow their passions. One of these individuals talked about being motivated by the academic and occupational success of his father. The other two students highlighted that their parents had not attained postsecondary degrees and wanted their children to have more opportunities. Only one student credited siblings with being an influence in his academic approach. He remarked, “It was more performance-based in comparison to them, I think. There may have been some trying to get more attention from the parents.” Professors.Professors had a varied impact on the academic orientation of most of the performance-approach participants. One student felt that her university professors did not really impact her approach to school. However, the other four students noted that certain professors did influence their achievement goal orientation to a certain extent. One student discussed the lasting impact from one of his instructors: “He really emphasized in me the value of school not just to achieve an end, like a job or good grades, that it translated over to your personal life.” For the other three students in this sample, their approach varied from professor to professor. Two of these individuals highlighted that they were eager to work hard in the classes of professors who invested a lot of effort into their courses and had a high standard of excellence. Conversely, for professors who were not as demanding or less invested, these two students communicated that they put in minimal effort to get the grade that they desired. The third participant referred to the effect of the professor’s temperament on her motivation. She mentioned how avoiding embarrassment was a stronger motivation in the class of a professor who was fairly blunt in dealings with students. On the other hand, she discussed how she had no fear of embarrassment with another professor who had a more gentle, gracious disposition. Personal motivations.The interviews and focus group highlighted a good deal of diversity in terms of the personal motivations of competition and personal growth. Both interviewees primarily defined academic success in terms of personal development, such as “applying yourself to the best of your abilities” and “what you can take away and apply, and how it’s changed you as a person.” However, unlike the female interview participant, who shared that she rarely compared herself to other students, the male interviewee explained that he was a naturally competitive person and that it bled into his academic life. He commented, “I do have some competition in me to achieve higher than my classmates at times to feed my ego a bit . . . to show that I can stand apart from my peers.” The other three focus group participants strongly embraced competition. For example, one participant stated, “I don’t want to just do good, but I want to be at the top . . . I want to be in the top ten.” Another student explained that if it were not for grades and classroom competition, he would not put nearly as much effort into assignments and exams. Although they shared differing views on the role of academic competition, all five participants viewed academic failure in a personal growth context. They unanimously agreed that walking away from a course without applying yourself or learning anything constituted failure Homeschool experience.The interview participant who rarely compared herself with others, a surprising statement from an individual with a performance-oriented goal, largely credited her lack of academic competitiveness to being home-schooled. Without other students around, she only had her own past performances to compete against. When asked if her approach would have been different had she attended a public school, she said, “If I had gone to a public or private school, I might have been more performance-approach oriented . . . compete more with others grades-wise.” Cultural influences.One participant discussed how influential cultural factors had been on her approach to school. In the country that she grew up in, education was highly valued and academic competition was fierce. She attributed her strong fear of failure largely to this intense cultural pressure. Three of the participants explained that their inclination towards academic competition was influenced by the competitive nature of the world beyond the walls of the university. For example, the business student that I interviewed pointed out that a competitive spirit is essential for success in the business world, where there is a constant struggle for jobs, promotions, and funding, among other things. Effects on personal well-being.Resources.One resource that all of the performance-approach participants discussed revolved around the small size of the university. Two students pointed to the benefits of how easy it was to network in a close-knit environment. One of these individuals stated, “I probably learn more just with the conversations that I’ve had with my friends than a lot of the stuff that I learn in class. Like, putting it into practice . . . thinking of ideas, brainstorming.” As an individual entering the business world, he talked about how important making connections like these will be for his future. Three students discussed how much they have enjoyed and benefitted from the discussion-based format that was possible with a smaller class size. Confidence in their personal efforts was a resource that was discussed by all five participants. Each participant communicated a strong internal locus of control. Regardless of the challenges that arose, such as a difficult professor, they shared that success was well within their grasp if they chose to apply themselves. One student commented:

In one of the interviews, a participant shared that he attained one of his highest test scores purely through rote memorization of the professor’s PowerPoint slides. While he did not feel that the high grade spoke to his intelligence, he said, “It showed that I did have the determination and the drive to actually take the time to go over those slides.” For three participants, family was primarily a source of support when it came to academics. These students communicated that their parents certainly encouraged and pushed them to fully apply themselves in their studies. However, these participants noted that they did not feel pressured to live up to the expectations of their family. One student discussed that her parents “emphasized just doing well, doing the best of my own abilities . . . being happy and not trying to define myself by my grades.” Another one of these students shared, “My mom always used to say to me, ‘Do your best and leave the rest.’ For me, that’s been a huge motivator.” The third student talked about how his parents never pressured their children to attend university, but instead supported them as they pursue their passions. Finally, all five individuals stated that they enjoy learning and have benefitted from studying a discipline that they were passionate about. This concept was exemplified by the comments of a focus group participant who said, “You know when you’re doing something that just lights up your brain. This is it. This is what I like to do.” Another student shared, “I value learning. I enjoy learning . . . It’s important to expand for your own sake.” Challenges.A prevalent challenge of this achievement goal group was the impact of linking grades to identity and self-worth. This was highlighted primarily by two female students in the focus group. One participant confessed that “I know my grades don’t define me, but sometimes I place my worth in them.” Later, she discussed how her definition of success, getting A’s and achieving better grades than her peers, was an aspect of herself that she was not proud of. Even though she approached academics with a competitive attitude, she acknowledged that comparisons between students were often a negative force that “switches the focus away from learning, to being better than others.” For the other participant, grades defined a large part of her identity. Of all the participants in this group, she was the only one to credit the fear of academic failure as being stronger than the pursuit of academic success. During the focus group, she discussed her fear “that people won’t think you’re smart if you don’t do well.” As a student who aspires to go on to graduate school, she talked about her significant struggles with the fear that her grades would not be high enough to be accepted into a program. She labeled this fear as significant because if she could not get into grad school, she would not know what to do with herself. While they did not discuss it at length, two other participants also mentioned their struggles with using grades to evaluate their worth. Four of the participants discussed the pressure of doing well in school as a means of setting themselves up for future success. Interestingly, when these individuals were asked what they believed the value of university to be, each of them immediately discussed the importance of “getting the piece of paper” that grants them access to good jobs, higher salaries, and social acceptance. It was at other points of focus group and interviews that these students discussed additional benefits, such as exploring areas of interest and “expanding your mind.” The expectations of family were stressors for two of the participants. One of these individuals mentioned:

Unlike this student, the second individual did not communicate that her family had explicit expectations for her to succeed academically. Instead, she talked about the pressure of being the first in her family “that’s going to go all the way” to attain a bachelor’s degree. Finally, four of the participants acknowledged competition with their peers as a challenge. While one of these students confessed her desire to be less competitive, the other three individuals embraced comparing their performance with others, much like the mastery-avoidance student. As one student explained:

Another student offered the thought that “there’s an element of pursuing excellence that comes from competing.” Indicators of personal well-being.Similar to the mastery-avoidance participant, the students with a performance-approach did not exhibit a consistent balance or imbalance between their resources and the challenges related to their education. One the one hand, all five participants revealed indicators that suggested states of optimal challenge. For example, one student expressed that she “definitely really enjoyed the psychology classes I took” and that she found her music courses to “be very stimulating and engaging.” Another student shared:

In alignment with these views, others expressed that they “loved” and “enjoyed” many of their classes. On the other hand, each of these individuals also offered comments that revealed a lack of balance between their resources and challenges. For various reasons (e.g., impressing family, the importance of school to self-worth and identity), three of the participants explained that they often face and struggle with worry and anxiety. Conversely, the other two participants stated that as a result of being under-challenged by professors in some of their courses, they sometimes feel bored and complacent. One of these individuals remarked: There are profs that, over time, I’ve maybe lost a respect or just kind of seen that I can do decent and not really have to engage the material. And I fell into this pit of just doing the mediocre, what I have to do to get by. In light of all of these comments, it is difficult to assess an overall sense of well-being for this group of participants. At times, these students seem to be in a state of flow, where the challenges that they encounter are well-matched with their resources, leading to a state of deep involvement and enjoyment. However, all five participants also shared experiences that indicate a lack of equilibrium for well-being, leading to consequences of anxiety or boredom. 4. Mastery-Approach GoalSix students with a mastery-approach goal participated in the study. I interviewed a male student and a female student. The focus group consisted of three male students and one female student. As a reminder, the mastery-approach goal is “characterized by seeking to develop greater competence, make progress, and to improve the self” (Reeve, 2009, p. 184). Underlying influences.Locus of control.With a few exceptions, this group had a fairly strong internal locus of control. Each individual expressed the belief that intelligence was fluid. One focus group participant commented:

Interestingly, there was not unanimous agreement that doing well was completely in the student’s control. Four participants firmly maintained that success was entirely based on how much effort they invested into their schoolwork. The other two students acknowledged that while a successful outcome primarily depended on the work ethic of the student, outside factors also played a role. One of these students brought up that the teaching style of certain professors could be an obstacle to success. She said:

The second student highlighted his difficulty and frustration with the liberal arts component of his degree. He believed that doing well was in his control for BHS courses that he was passionate about but doubted his ability in courses of other disciplines that he was required to take. Family.For most of the participants in this group, family only had a weak effect on their current achievement goal. Three participants talked about how they experienced some degree of pressure or expectation from their parents in high school. The other three communicated that their parents were incredibly supportive and encouraging of their academic pursuits. However, the most prevalent idea that participants communicated was that a mastery-approach goal was something that they cultivated for themselves. Five of the participants talked about how their interests and values were the driving force behind their university education. During the focus group, one student stated, “With my university education, I decided to come to [this university]. I decided what I wanted to do, and all my courses, I pick. Like, it’s all mine. It’s more for me than for them.” Only one participant talked about the motivation to please a parent with his academic performance. Furthermore, he explicitly discussed how this was not a source of pressure or expectation, but more so an opportunity to share the joy of his achievements with his mother. Professors.With regards to their achievement goal, all six students talked about the importance of professorial influence. There was a general consensus that their mastery-approach goal was strongly impacted by professors who challenged them. In my interviews, both participants spoke at great lengths about certain professors who pushed them to achieve their potential. For instance, one of these interviewees recounted his experience with an instructor:

Three of the four focus group participants communicated the same idea. These individuals espoused a mastery-approach goal in the courses where professors challenged them to critically evaluate their beliefs and perspectives. One of these students noted, “I think with professors that are more passionate, it’s kind of contagious.” On the other hand, these three students highlighted that they were more concerned with just getting a good grade in the courses of professors who did not seem to care as much about the content. The final focus group participant did not talk about the value of being challenged by her professors. Instead, she discussed the importance she placed on the comments that she received on assignments from professors. She highlighted that she valued this feedback more highly than the grade, and that she relied on professor comments to track her progress and knowledge. Personal motivations.All six participants stated that the desire to develop as a student and as a person was a very strong motivation. Both interviewees mentioned that earlier in life, they were very motivated by comparing themselves to their peers, both inside and outside of the classroom. However, these two individuals indicated that at the present moment, personal growth was a strong motivation in all facets of life. This was evident in the remarks of an interviewee who stated, “I want to be the best version of myself that I can be . . . so if I’m not constantly growing and learning and self-aware, which is where that starts, then I can’t do that.” All four focus group participants also pointed to personal growth as a significant motivation. When asked how they defined academic failure, each individual responded with the idea of not learning something valuable to take away from a course. One participant explained it this way: “Courses should affect you and change you . . . if you leave a course not just not learning anything, but just the exact same as when you walked in, that’s a bit of a failure.” Surprisingly, three of the four focus group participants and one of the interviewees acknowledged that they also were motivated by, and valued, peer comparison and competition. However, they emphasized that the tone and level of this comparison was important. Rather than being motivated to outperform their peers, they talked about how the efforts of others inspired them to work harder as well. Mature student experience.The two individuals who participated in interviews highlighted the importance of being a mature student. For both students, it was their second time attending a postsecondary institution. During the time away from school, both individuals had personal experiences that caused them to reevaluate their goals and values. One student described the impact of his travel experiences during this time:

Homeschool experience.One participant mentioned how influential being home-schooled was for her approach to school, much like one of the performance-approach participants had discussed. In this environment, she did not have academic peers to compete with. Additionally, she explained, “For most of my home-school education, mastery-approach was really easy because it’s not structured the same way as high school. Your interests drive your learning more as well as your time commitment.” This played an important role in her current approach to academics. Necessity/value of competition.Three focus group participants stated that they adopted a mastery-approach goal, but also a performance-approach goal. They noted that while their interests and passion for learning were strong motivating forces, they also realized the necessity of maintaining a competitive GPA in order to attend graduate school or attain a good job. One of these students highlighted:

Effects on personal well-being.Resources.All six participants had a great deal to say about their personal resources. There was unanimous agreement concerning the rewarding nature of their relationships and interactions with professors. The participants highlighted how much they appreciated how understanding and available the instructors at the university were. One of these students stated, “You’re not just a number. They want to see you excel; they help you to do so.” An interview participant expressed, “It’s not as much of a hierarchy when you feel like your profs are coming alongside you and trying to help you and lift you up . . . that’s one of the things that I love about this school.” Four participants listed family as a resource. These individuals described family and especially parents as supportive, as well as respectful, of the student’s autonomy in their academic choices. In the focus group, one student talked about his family’s encouragement:

Another student recounted that there was never a sense of “negative expectation” from his family, just genuine interest. A willingness to work hard was also communicated to be an asset. All six participants communicated that doing well was at least mostly in their control. When asked if doing well was in his control, one participant responded, “Definitely. What you put into it is what you’re gonna get out of it. I see it as an investment. I’m here and I’m learning, so I’m gonna get the most out of it while I’m here.” Another student discussed that she had overcome her writing struggles by seeking out additional assistance from professors and other students outside of class. By taking the initiative to work through drafts of her work with others well in advance of deadlines, she commented that she had seen her confidence and ability steadily improve. Finally, there was a general consensus that it was a pleasure to study topics of interest. Many participants expressed how much they truly enjoyed the connection of their personal passions to their study. When asked how she decided upon her major, one of the interviewees responded, “It’s just a passion of mine. I love it.” In response to the same question, another participant answered, “I’m just really curious about people mostly. I like to learn about people and their motivations.” Challenges.Even with the many benefits, the mastery-approach group did highlight some challenges as well. Three students aired their frustrations over the liberal arts aspect of their programs. Though they did acknowledge that there was some value in branching out into other disciplines, these individuals maintained that it was difficult and irritating to be pulled in so many different directions, many of which did not interest them. One participant remarked, “I’m enjoying getting further into my degree and getting more condensed . . . it’s easier than being a being a philosopher one moment and sociology the next.” Additionally, they expressed that for many of the classes they were “forced” to take, they were solely there for the course credit. All the participants related how much they have appreciated being challenged by their peers and instructors. They highly valued how their professors have pushed them to pursue excellence and think for themselves. One student remarked:

In the university’s close-knit setting, these participants expressed that classes became interactive opportunities to engage in dialogue with the professor and other students, a place where a diversity of opinions and ideas were shared. Another challenge that was discussed was the small size of the university. While this was also cited as a benefit of the school, four participants discussed that it was also a source of discontentment. Because of the university’s limited resources, it could not offer as many of the specialized courses in areas that these students were truly passionate about. In addition, one participant discussed his annoyance over the limited number of professors. He pointed out that if there was a professor in his program to whom he did not respond well, “it doesn’t really matter because you are stuck with them for the next three, four years.” Finally, one participant mentioned the detrimental impact of the close student/professor relationships at the university. Over the course of our discussion, this participant juxtaposed two experiences where she received a grade that disappointed her. The first example involved failing a final exam for a course in another discipline. In the other instance, she received a B as her final grade in the class of a professor that she really admired and appreciated. Of those two experiences, she expressed that she felt worse about the B than failing the exam. When asked to explain her reasoning, she answered, “I didn’t put my hundred percent in there, and I do feel like my professor deserved that. He puts a lot of effort into it. He’s very passionate about the content, and I kind of feel like I failed him.” Indicators of personal well-being.At times, the mastery-approach participants did not display a balance of resources and challenges. The student who worried about disappointing a professor (see p. 41) shared that, to a limited extent, she wrestled with the fear of failure. As a mature student and mom with children who depend on her, she explained, “I have a lot on the line, right. I have a lot invested in this. So I want to do well . . . I don’t want to fail.” In addition, three students discussed their reactions of boredom and frustration over some of the required classes in other disciplines. In the focus group, one participant commented, “Some classes I’ve just rushed through to try and get the art credit or the senior religion credit.” However, feelings of fear or boredom tended to be exceptions rather than a generalizable pattern. After revealing her fear of failure, the mature student continued on, stating, “I think everybody has a fear of failure, but that’s not my focus. I think if that was my focus, it would be pulling me back a little bit instead of driving forward and pushing myself to succeed.” Likewise, other participants communicated that they were not particularly anxious or concerned over potential failure or disappointment. One student commented:

Another student explained, “I don’t consider failure really. I’m just looking towards trying and learning.” Additionally, the students who expressed their boredom at some of their mandatory classes acknowledged their value and importance. One of these individuals mentioned, “It is a liberal arts school and you have to take a diversity of courses. That is a total benefit in some regards.” Another focus group participant added, “I wish that [students] would want to learn more. Obviously, there’s going to be stuff that’s dry . . . but I think it would be cool if people really wanted to learn the stuff.” Achievement Goal IdentificationTo conclude this results section, it is important to note an area of commonality across all four achievement goal groups. During the focus group and individual interviews, all participants were presented with descriptions for each of the achievement goals and asked to identify which goal(s) they thought most aptly described their approach to academics. This exercise yielded three interesting findings. First, most participants, regardless of which group they were in, found that aspects of two or more of the goals really resonated with their academic approach. For example, one of the performance-approach participants remarked: