Tyrant or Temptress: Deciphering Meaning from Stella's Sole Reply in Sir Philip Sidney's Fourth Song

By

2017, Vol. 9 No. 02 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

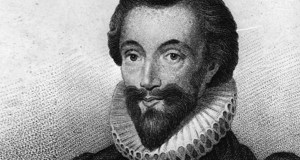

First published in 1591 but thought to be composed sometime during the previous decade, Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella recounts the evolution of the relationship between the fictional, titular characters primarily from young Astrophil’s point of view. Consisting of 110 sonnets and 11 songs, the English poet’s sonnet sequence begins with a love-struck Astrophil narrating both his motivations for writing the various pieces and his initial struggle to begin translating his internal sentiments into poetic verse. The work goes on to document the transition of Astrophil’s newfound affections from awestruck admiration and persistent efforts at courting, to discouraged and scornful disdain for his former beloved, to hopeless resignation that he will forever be plagued by his love for the beautiful Stella. The turning point in the youthful lover’s shift from amorous suitor to dejected bachelor occurs when he is finally alone with Stella as depicted in “Fourth Song.” Unlike the clear majority of other works in this sequence where only the lover is speaking, this song is the first in which the beloved is granted the ability to answer Astrophil’s numerous aggressive advances for herself. Despite being limited to a single line, Stella’s response of “No, no, no, no, my Deare, let bee” to each of Astrophil’s attempts to woo her provides imperative insight into the character of the lovely Stella, as well as the nature of her relationship with Astrophil (“Fourth Song” 6). "No, no, no, no, my Deare, let bee" Although Stella’s brief reply is typically read as the stern rejection of Astrophil’s many propositions and the final straw in his fruitless pursuit of her, it can also be viewed as a form of coy flirtation intended to prolong their innocent courtship. This possible interpretation of Stella’s only line transforms her relationship with Astrophil from a one-sided and potentially predatory pursuit to a mutually enjoyable affair between equally invested parties. Through both its surrounding context within the song and its own content, this line shifts the reader’s perception of Stella from uninterested, modest, and cold-hearted to flirtatious, enigmatic, and enticing, thus changing the tone of Sidney’s entire sonnet sequence.Prior to Stella’s first utterance of speech, Sidney begins painting the picture of her as complicit in their encounter through Astrophil’s opening dialogue. The young lover’s reference to his own “whispering voyce” highlights his awareness of the need for secrecy in their meeting to avoid attracting unwanted attention (“Fourth Song” 3). When examined on its own, this small detail may seem to suggest Astrophil has somehow snuck up on an unsuspecting Stella, but when considered in conjunction with his preceding claim of “now here you are” upon finding Stella, it can be inferred that this conversation is neither unanticipated nor a coincidence (“Fourth Song” 1). The inclusion of the word “now” in Astrophil’s first line gives the impression that he and Stella have been conspiring to meet alone for some time but have only just succeeded in doing so for the first time. The young lover’s continued description of Stella as “fit to heare and ease [his] care” indicates that she is expecting his arrival and prepared for the ensuing conversation rather than baffled at his sudden appearance (“Fourth Song” 2). By implying that the lovers’ secret meeting is the result of extensive planning and preparation, Sidney uses these brief speeches to rob Stella of her perceived naivety while simultaneously implicating her in the organizing of this forbidden rendezvous before she has even spoken a single word Sidney continues to refute the idea of Stella as the innocent and unwitting participant in this encounter with her would-be suitor throughout the remainder of this song. Astrophil’s assertion that the two are conversing while “Night hath closde all in her cloke” further emphasizes their mutual desire for privacy and discretion (“Fourth Song” 7). Playing on the perception of darkness as a place of potential mystery and trickery, Sidney characterizes this meeting of lover and beloved as something secretive that must be shrouded in night and hidden from others’ view. This idea of their affair as forbidden and needing to be concealed is furthered by Astrophil’s assurance to Stella that the noise she heard “was but a mouse” (“Fourth Song” 25). The necessity of this hasty reply indicates that Stella exhibited jumpy and anxious behavior in response to this unknown but harmless noise, a reaction indicative of her culpability in this encounter and subsequent fear of being discovered. Stella’s involvement is most blatant in Astrophil’s claim that her “faire Mother is abed” and under the impression that her seemingly trustworthy daughter is “writ(ing) letters” (“Fourth Song” 37,39). Here, Astrophil identifies a moment of dishonesty for which Stella is solely responsible, as it is highly inconceivable that the male lover, without the aid of his beloved, could somehow convince Stella’s mother that she is composing epistles rather than engaging in unsupervised conversation with a suitor—highly inappropriate behavior for a young woman during this time. In his many attempts to quell the fears of his beloved, the young Astrophil inadvertently highlights Stella’s propensity for deception and willingness to break from societal expectations to ensure the success of their attempt to meet. The characterization of Stella as a coquettish and willing beloved is perhaps best evidenced by the diction and syntax within her repeated response. Beginning with “no, no, no, no,” it is often assumed that Stella’s reply is a final and damning rejection of Astrophil’s actions, but when examined with the previously established image of Stella in mind, this string of negations can be read as encouraging, seductive flirting (“Fourth Song” 6). In accordance with the perception of this line as a rebuff to Astrophil, Stella’s words would be expected to become increasingly emphatic with each passing syllable; however, these exclamations can just as easily be read as becoming less forceful and more playfully kittenish. As this tale is narrated principally by the young, male consort, it lacks any direct accounts of Stella’s actions, relying instead on his reactions to her behavior to discern the emotional framework surrounding this statement. Based on both Stella’s panicked response to the rustling of the aforementioned mouse and Astrophil’s eagerness to quiet her fears in order to return to whatever they were doing, the reading of these words as becoming progressively less definitive and more suggestive gains both legitimacy and probability. Moreover, the fact that Stella’s response remains “no, no, no, no” in the face of Astrophil’s increasingly desperate and convincing arguments highlights the static nature and inherent weakness of her objection. Despite its apparent ineffectiveness, Stella’s refusal to adapt or alter her response is evidence that she does not truly want Astrophil to halt his advances but wishes to continue their covert exchange. Any surviving semblance of rejection in Stella’s string of no’s is immediately undercut by the rest of her reply. Stella’s inclusion of the phrase “my Deare” directly following her initial assertion of rejection negates the credibility, harshness, and finality of her refusal (“Fourth Song” 6). By referring to Astrophil using this universal term of endearment, Stella reveals that she possesses positive feelings of affection for her potential suitor. This is further evidenced by her use of the first-person possessive pronoun “my” to denote her close relationship with Astrophil. Without this addition, Stella’s use of “Deare” could possibly be construed as a comment on Astrophil’s overall goodness rather than an admission of her love for him, but Sidney’s attention to detail in this moment ensures that the young maiden’s flirty nature and desires for Astrophil are evident (“Fourth Song 6). When combined with the knowledge of Stella’s role in facilitating their private encounter, the use of this seemingly insignificant pronoun and pet name can be viewed as indicative of some underlying history of flirtation and mutual exchange of ardent sentiments between the two young lovers that has led them to the conversation documented in this song. Similarly, the appearance of the ambiguous phrase “let bee” at the close of her declaration calls into question the outcome that Stella desires (“Fourth Song” 6). If she were indeed rebutting her lover’s propositions, it seems logical for the word “me” to appear in the middle of this phrase to signify Stella’s longing to be free of Astrophil’s advances. However, the omission of any word to indicate what Stella wishes to be left alone allows for this command to be read as an imperative concerning their current situation rather than Stella herself. This understanding casts Stella as the torturous, flirtatious tease by implying that she relishes being the object of Astrophil’s undivided attention and works to prolong their coquettish exchange without any intention of ever fulfilling Astrophil’s carnal desires. Her refusal to bring the situation to a climax by either allowing their relationship to become physical or ending Astrophil’s futile pursuit of her prompts Stella to imprison Astrophil in a seemingly endless and frustrating form of sexual limbo. By simultaneously leading him on and promptly commanding him to leave their unsatisfying and tumultuous relationship as it is, Stella manipulates Astrophil’s affections to suit her own personal pleasure with no regard for how this affects the young lover. Despite limiting her to a single line, Sidney makes clear through both the surrounding circumstances and his carefully crafted phrasing that Stella is as invested as Astrophil in this brief encounter and the continuance of their relationship. Unlike Astrophil, however, Stella’s motivations appear to be self-serving, causing her to exploit the male youth’s sincere affections to serve her own purposes. By contrasting the evidence that Stella, motivated by love, has gone to immense trouble to arrange and assure the secrecy of this meeting with the egocentric and manipulative qualities of her speech, the poet seems to provide a means of justification for Astrophil’s attack on Stella’s character and denunciation of his love present in “Fifth Song.” Through his use of both direct and indirect characterization, Sidney creates an image of Stella as the calculating, frisky vixen that alters the readers’ initial perception of her and allows them to sympathize with Astrophil, thereby shifting their understanding of this sonnet sequence from centering around a young woman infinitely pursued by a love-crazed man, to the story of a smitten lover whose feelings are continually toyed with for the amusement of his beloved. ReferencesSidney, Sir Phillip. “Fourth Song.” Astrophel and Stella, edited by Will Jonson, CreateSpace. Independent Publishing Platform, 2014, 62-64. Print. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |