Featured Article:The Burden of Disarmament: UN Peacekeeping Operations & Illicit Weapons

By

2010, Vol. 2 No. 01 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

"Disarmament is not an end in itself. The end is peace, and security is one of its essential elements.” It has become undeniable that illicit weaponry, specifically small arms and light weapons pose an unprecedented global security threat. In fact it may almost be acceptable to say that with the turn of the 21st century, we witness a world which is more further armed (whether legally or illegally) than at any other time in human history. That being said, weapons are readily available to a world overwhelmed with intra state conflict and terrorism, both of which have established themselves as the new post cold-war era widespread types of conflict. Arms transfers have the capacity to directly and indirectly undermine development by inducing insecurity, contributing to abuses of power, and diverting arms into illegitimate hands.

An increase in conflicting geopolitical interest and tendency for violence has seen the demand for weapons (especially small arms) increase on a continuous basis. All the meanwhile, these conflicts have called on the United Nations (and other multilateral institutions1) operations to restore the peace. While operational success of these efforts has hindered upon the fact that states face a difficulty in agreeing on what the common challenges are, let alone the collective strategies to address them (Prins, 2006:110), one thing remains evident, and that is the fact that small arms and light weapons pose a security challenge to UN Peacekeeping Personnel as well.

This article analyzes the challenges facing the international community when it comes to arriving at collective strategies to address arms control, the feasibility of disarmament under the context of UN Peacekeeping operations, and the threat it poses from a military perspective as opposed to a humanitarian one. Furthermore, this article will consider that the ATT policy on engagement as a product of an unstable decision-making process at the international and domestic levels in which perceived humanitarian and political benefits are weighed against the perceived costs and risks of involvement (Hubert et al. 2000:X - See Figure A Appendix). The aim is to tackle an overall perspective on arms control from a preventive security approach focusing on UN Peacekeeping Operations. The Preventive Security Impact“A weapon is a device for making your enemy change his mind.” Indeed modernization has yielded an impact on numerous societies and resulted in technological advancements that help shape the nature of the global interconnectedness we experience today, but on another hand the “old politics” mindset continues to exist despite the overwhelming driving force of globalization. Politicians worldwide with extensive Cold War experience find themselves facing a world structured along different lines. None the less they still champion the notion of security under the context of national defense as opposed to collective global preventive human security. Perhaps it would be accurate to say that while the Cold War ended, its ripple waves can still be felt today in the remnants it has left behind. The first of which is the sudden spike in illegal arm transfers worldwide ( as a result of massive stockpiles being abandoned and corruption that saw the other half fall into the wrong hands); secondly, the remnant global political psyche of exaggerated national interest. It goes without saying that as our world becomes ever more interconnected, so does our security. From a Human Security perspective, this new concept of “protection and empowerment” goes beyond the fact that it is only our physical security that is jeopardized. While arms transfers can contribute to peace and development by deterring rebellion and aggression, strengthening legitimate security functions, and helping governments combat crime and violence, arms transfers also have the capacity to directly and indirectly undermine development, by inducing insecurity, contributing to abuses of power, and diverting arms into illegitimate hands (Small Arms Survey 2004:10) Eventually of course one can draw out that arms are not only expensive in terms of their monetary value, but they proliferate on the account of other vital human security pillars. To invest into arms is an equation that yields the same results always (more so amongst developing nations):

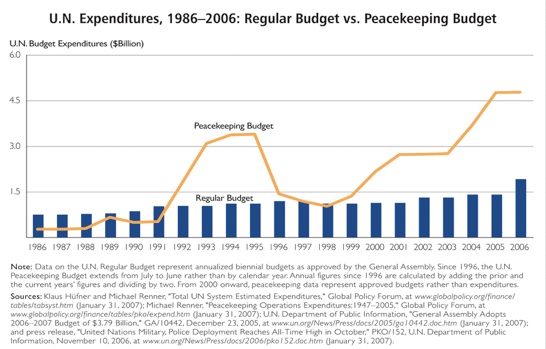

Now if we take into consideration the fact that In 2002 alone, arms deliveries to Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa (continents/ regions in most need of development assistance programs) constituted 66.7 per cent of the value of all arms deliveries worldwide, with a monetary value of nearly US$17bn and the fact that the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council accounted for 90 per cent of those deliveries (Amnesty International 2004:4) it becomes remarkable to see that there are two faces to the same coin we toss. On the one hand billions are spent on development and on another billions on arms (which in many instances hampers development eventually). The Variables of Disarmament & Control“To the extent that money can solve conflicts and potential conflicts, not a huge amount is required compared to what the world is prepared to spend on everything else, including defense." Why should disarmament even concern us? Excellent question; now when we take into account the fact that small arms result in at least a third of a million people killed each year, directly with conventional weapons and many more die, are injured, abused, forcibly displaced and bereaved as a result of armed violence, that indicates that on average, up to one thousand people die every day as a direct result of armed violence (Arms Without Borders 2006:4), it becomes apparent then that we not only should be concerned, rather alarmed. The impact of small arms goes beyond the fact that they simply pose a physical security threat. As mentioned earlier, in an age of globalization, even the threats we face are interconnected, the proliferation of these arms has been shown to hinder development; the cost of lost productivity from non-conflict or criminal violence alone is about USD 95 billion and may reach as high as USD 163 billion per year. (Geneva Declaration 2006:10) Although some steps have been taken in the right direction, for example since early 2001, US-supported programs in 23 countries have resulted in approximately 800,000 SALWs and 80 million rounds of ammunition destroyed (Garcia 2006:10), the world continues to be littered with illegal SALWs which pose a serious risk to global human security. Approximately 8 million small arms and light weapons are produced each year which result in over 1000 deaths per day (Amnesty International 2008) …While this appears to be outragous, to date only about 40 states (including the US and UK) have enacted laws and regulations for controlling the business of arms brokering (Amnesty International 2008). The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) has been an initiative aimed at addressing issues such as those mentioned above and more, however while states have already committed themselves to establishing such an agreement in Article 26 of the UN Charter and the UN Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All its Aspects (Arias Foundation 2008:6), they continue to face challenges with arriving at a consensus in the framework of an ATT. Peacekeeping - Operational Challenges"For all the civilians saved thanks to the presence of peacekeepers, there have been those who were lost – the United Nations personnel who sacrificed their lives for a noble cause.” The United Nations Peacekeeping website itself states that “The term "Peacekeeping" is not found in the United Nations Charter and defies simple definition. Dag Hammarskjöld, the second UN Secretary-General, referred to it as belonging to "Chapter Six and a Half" of the Charter, placing it between traditional methods of resolving disputes peacefully, such as negotiation and mediation under Chapter VI, and more forceful action as authorized under Chapter VII.” (UNDPKO) Hence not only is there an issue of inaction, but simple definitions and operational legislation also appear to be problematic. From the above one would gather that Peacekeeping is realistically infeasible, however it is practically applicable. In an age where global threats are light years ahead of global preparedness to meet them, this statement can be rather disturbing. Let aside the political variables in the build up to any peacekeeping mission, too many sensitive issues hinder operational success, and in many instances post-operational unrest occurs. (Fig. B. Appendix). One of these operational issues is the cost of peacekeeping itself. (Fig C. Appendix) Now on a different note, Global Compliance Principals (as outlined by Amnesty International) identify the responsibility of the international community through this lens: “States shall not authorize International transfers of arms or ammunition where they will be used or are likely to be used for violations of international law, which include Breaches of the UN Charter and customary law rules relating to the use of force, gross violations of International human rights law, serious violations of international humanitarian law, Acts of genocide or crimes against humanity.” (Amnesty International 2007:4) For some reason or another these principals do not explicitly require states to not authorize the transfer of arms during peacekeeping operations. In fact it appears as though only the international criminal court has taken into consideration some form of accountability that might be applied during peacekeeping operations, when it states that a war crime includes: “Intentionally directing attacks against personnel, installations, material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistance or peacekeeping mission in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, as long as they are entitled to the protection given to civilians or civilian objects under the international law of armed conflict” (ICRC 2007:20) But for some reason it fails to make any reference to the parties involved in the transfer of the weapons (which in most cases are SALWs) used to facilitate a war crime. Moreover, the majority of SALWs producers have not ratified the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court. Some of these countries include: the United States, Israel (both which signed and later unsigned in 2002) and Russia. In 1996, the Disarmament Commission adopted Guidelines for international arms transfers, which in summary included numerous principles; one of which requires member states to “ensure that the level of armaments is commensurate with their legitimate self-defense and security requirements, including their ability to participate in United Nations peacekeeping operations” (UNGA 2008: A63/334). While acknowledging the legal challenges mentioned above, we also need to pay considerable attention to operational challenges Peacekeeping forces experience on the ground. That being said, logistics and funding are serious issues when it comes to carrying out any peace keeping mission. Systemic success and failure can thus be defined in operational terms according to the UN’s ability to find the personnel and resources to fulfill its operational needs, but the system is not simply an operational matter: meeting its requirements is a political business that involves three categories of states interacting through a ‘hierarchical relationship of supply and demand, both in terms of manpower and money’ (Gowan 2006:458). One could only imagine the burden of such a task. Irrespective of the Blue Flag the DPKO operates under, local populations often find themselves having to take orders from “out-siders” and even though these peacekeepers come with noble intentions they face overwhelming social challenges. If we were to consider “cross-cultural communication” the key to operational success, one must then wonder how many nationals are employed under the jurisdiction of DPKO while operating in any “post-conflict” situation. The answer is: not so many. The logic behind this is that one could not peacefully intervene amongst parties in conflict by hiring individuals from these same conflicting parties to craft the peace; indeed a catch 22. With this taken into consideration, it becomes clearer that not only is the process of financing an operation, securing the necessary equipment, and receiving proper cultural training an issue, but rather hiring “the right people” is an issue as vital as well. This absence of local recruits hinders the process of gathering crucial intelligence, and as a result this usually leads to one of two unyielding end outcomes: marginal success or complete failure. Following the international debacles in Bosnia, Rwanda and Somalia, peacekeeping encountered widespread criticism: extremists advocated abandoning the tool altogether; minimalists argued for limited deployment and a resumption of traditionally characterized missions; optimists defended peacekeeping, yet subjected it to lengthy discussions on how to strengthen it through serious reform measures (Duffey 2000:142) Disarmament Under the Context of Peacekeeping“The world organization debates disarmament in one room and, in the next room, moves the knights and pawns that make national arms imperative” With respect to the "reduction" measures, an important recommendation introduced by the UN Panel of Governmental Experts on Small Arms - December 12, 1995 - was for the development of guidelines to assist peace negotiators and peacekeeping missions in planning and carrying out the disarmament of former combatants, the collection and destruction of weapons and so forth. This recommendation stemmed from the realization that the lack of clear guidelines in peace agreements and the mandates of peacekeeping missions often resulted in the aggravation of the situation in post-conflict regions - Paragraph 79-d (Donowaki 2000:49) The debate of disarmament and destruction centers around one remarkable question and that is whether or not funds should be designated for destroying weapons seized by UN peacekeepers during\post conflict or whether these same funds should be used in post conflict reconstruction and long term development? And while this question has fascinated academics and policy makers alike, the cost benefit analysis of storage and maintenance versus destruction has been a prominent issue as well. However, when considering the costs of destruction over the costs associated with safe long-term storage and maintenance, destruction tends to be economically advantageous. (UNSC S/2008/258) Furthermore it is quite important to remember that disarmament (Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration) in its most basic form consists of a combination of legal reforms to regulate civilian firearms licensing and ownership and technical interventions to collect and destroy retrieved or surplus weapons. Hence disarmament is more than a simple plan of retrieving weapons (Small Arms Survey website). The success of such operations hinders upon the fact that they need to be measured, accounted for, and that the effort needs to be a “one way process”, unfortunately that is not the case at all. There is an overwhelming absence of evidence to account for success or its lack thereof and when the evidence is usually made available, it is hardly reassuring. For example, the estimate of the total number of small arms and light weapons in the RoC when fighting ended lies between 67,000 and 80,000. By 2003, collection programs had recovered about 28 per cent of the total (Small Arms Survey 2003:8). In fact, even the UN Security Council Reports seem to recognize this challenge, for example, the report on The Role of United Nations Peacekeeping in Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (S/2000/101) notes: “Even if full disarmament and demilitarization prove unachievable, a credible programme of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration may nonetheless make a key contribution to strengthening confidence between former factions and enhancing the momentum toward stability.” (UNSC S/2000/101). VI. Revisiting Previous ChallengesDespite efforts to control arms, two peacekeeping missions — the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) and the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) — have been mandated by the Council to assist in monitoring the arms embargoes in their respective areas… in its September 2007 report, the Group expressed the view that the monitoring of the implementation of the arms embargo was still not very effective (S/2007/611). Historically, 13 United Nations arms embargoes imposed in the last decade have been systematically violated (Control Arms 2006). There are constantly changing conditions on the ground that hamper progress, in Côte d’Ivoire for example, rebel leader Guillaume Soro made clear that his fighters would only hand in their guns if they were satisfied that the 2005 elections would be free and fair (UNOCHA 2004). It is an attitude that is difficult to contest, especially in light of the fact that UN Peacekeepers are discouraged from using force. DDR requires consent, which at the end of the day is a concession hardly attainable in conflict plagued regions worldwide, it also comes at the enormous costs of both lives and funds (please see Fig D Appendix). Another example is Mozambique 1992-94; the first Peace keeping operation to include a weapons destruction component was carried out, ONUMOZ demobilized around 100,000 combatants and collected 214,000 weapons. Impressive indeed, yet the mission had failed to accomplish the more modest goal of destroying the weapons it had collected, leaving them behind to circulate freely (Garcia 2006:73). Logistically, Peacekeeping operations have always faced problems as well. For example, State and UN officials indicated that member states had committed to fill some of the requirements, particularly for the operation in Darfur, but as of November 2008, the troops were not in place nor was it known when they all would be, UN officials and reports also note that the lack of needed troops, police, and civilians has hindered some operations from executing their mandates (USGAO 2008:4) Of course combatants are the primary target in DDR programs, however the realities posed by armed civilians, militias and civil defense groups/forces also need to be acknowledged more consistently. Whilst the blurred line between civilians and combatants is generally accepted, in DDR programs the distinction is largely maintained, insufficiently addressing the challenges that armed civilians pose for effective weapons control (Buchanan 2006:2). The public is hardly ever incorporated within the DDR framework, hence the result is indeed a disarmament of combatants, but the availability of weapons overall persists, and the potential for future conflict remains. The threat of persistent arms circulation goes beyond simply posing a national security threat where it exists; if these arms were not collected and destroyed following a peace settlement, they might end up in another part of the world fuelling conflict and crime (Garcia 2006:67). All this being said, one must note that it seems clear that whether in the framework of crime prevention or peace-building, practical disarmament by itself can do little to remedy the problems of weapons proliferation and misuse in a society (Faltas et al. 2001:8); a grander global effort is needed, one that creates a high standard accountable system of monitoring and transfer of weapons that could curb their availability and as a result reduce violence worldwide. Any attempt at curbing corruption is a favorable one; according to the NGO Transparency International, of all industries ranked in its 1999 Bribe Payers Index, the arms industry was considered the second most likely to involve bribes (Small Arms Survey et al. 2004:8) Perhaps the best way forward is to adopt a treaty that addresses the corruption involved in this industry in a more vigorous manner. An Alternative to the ATT?“If you are a gun manufacturer, the product you make is not subject to safety regulation by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. Toy guns are subject to safety regulation; water pistols are, but not real guns.” Despite the majority of leading “arms producing” nations refusing to succumb to a global arms treaty, 153 states voted in favor of the ATT Resolution and over 90 states affirmed the feasibility of an ATT in their views submitted to the Secretary-General during the consultation process that took place in 2007, it is clear that there is considerable support among states for the adoption of common international standards for the import, export and transfer of conventional weapons (Parker 2008:2). In addition to succumbing to a stalemate, this treaty has yet to yield any consensus, let alone universal impact. It goes without saying that a treaty of this magnitude requires global consensus, and this crucial component appears to be far fetched. An interesting alternative approach would perhaps be a treaty that collectively applies to all “buyer states”. One that would set a standard of purchase amongst these states which eventually will allow for more realistic monitoring mechanisms to be put in place to control the expected standards that “producer states” must abide by; whether the largest producers are on board or not becomes irrelevant under these circumstances as they would have to answer to their customers’ demands (after all these products must be sold as they generate enormous economical rewards), which in this case would be an application of an international treaty (verifications of product, licenses, traceability from origin to destination, etc) that may serve as an alternative to an ATT and even the CCW for that matter. Like the ATT this alternative will would also require that effective national arms transfer control mechanisms should include provisions regulating the import, export, transit, transshipment and brokering of weapons as well as an effective customs and enforcement capacity that is backed up by clear legal penalties (Saferworld 2008:3). Such an approach would serve in the interests of peacekeepers as well, as most of the weapons would be traceable, hence making it easier to apprehend criminals, etc. However one must wonder, without a good mechanism of governance and agonizing corruption existing in most “customer states”, how effective would this alternative be? Where to From Here?“We used to wonder where war lived, what it was that made it so vile. And now we realize that we know where it lives...inside ourselves.” Although there is little to attribute to peacekeeping under this section, it closely relates to its necessity in the future given current global indicators. Less than a decade ago, 25 African countries were engaged in armed conflict or were experiencing severe political crises and turbulence; within the last six years, this dire state has dramatically improved, today, only about 3 African countries can be considered to be in a situation of violent conflict and few countries are facing deep political crises (UNOSAA 2006:7). While theorists may debate the realist and liberal standpoints, it is difficult to see how the issue of global anarchy will ever be resolved. The need for UN Peacekeepers will mostly likely remain necessary in the wake of the 21st century and well into the turn of the century that follows. Despite global efforts to attain peace and pursue global treaties that are expected to keep arms and wars at bay, the risk of war will always remain, we only try to minimize it. Concluding Thoughts"Every gun, every warship, every tank and every military aircraft built is, in the final analysis, a theft from those who are hungry and are not fed, from those who are naked and are not clothed." So in the turn of this new century we reflect upon the fact that in 1994 the United Nations put forth an estimate that affirmed that in order to achieve universal coverage of the basic necessitates of life and human sustainability, the international community would have to allocate these investments to these sectors respectively: Primary Schooling = 3 Billion; Water and Sanitation = 5 Billion; Basic Health and Nutrition = 11 Billion (Figures are in USD). The UN went on to highlight that during the time these figures were put in place the world was already spending 816 Billion USD on its military budget (UNDP 1994) … The dilemma with “Disarmament” is that it adds to the latter budget as opposed to those allocated for more immediate human security threats. On the note of the feasibility of peacekeeping operations, the current Secretary General, Mr. Ban Ki Moon has called for a restructuring initiative that aims at splitting the current Department of Peacekeeping Operations –DPKO- into a Department of Peace Operations and a Department of Field Support, both headed by an Under-Secretary-General, the managerial level of the current DPKO chief. (UNNC 2007) However, we have yet to learn of the impact such an initiative will have on the effectiveness of DDR under the context of Peacekeeping. I leave this paper open ended with a question that will perhaps apply time and time again to come: “When would it begin to make sense to states that not only is human security on the line, rather state security as well? The two simply go hand in hand”. In an age of intensifying interconnectedness, to address one issue is to address another and vice versa; “multilateralism” that minds and attends to all the variables related to an issue is an approach that applies to humanitarian action as well. While the UN-PoA attempts to recognize this link, it barely raises a convincing strategy: We the states are - “Concerned also by the implications that poverty and underdevelopment may have for the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons in all its aspects” (UN/A/Conf.192/15) Unfortunately we remain at the mercy of time in pursuit of an answer to the question raised above… all the mean while peacekeeping operations are threatened, arms proliferated, and the future of the both the developed and developing worlds is jeopardized. ReferencesAmnesty International . “Blood at the Crossroads:Making the case for a global Arms Trade Treaty” - ACT 30/017/2008 - http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ACT30/017/2008/en/b7fe1dda-83e0-11dd-8e5e-43ea85d15a69/act300172008en.html Arias Foundation for Peace and Human Progress. “The Arms Trade Treaty: A Nobel Peace Laureates Initiative” P.6 2008 - http://www.armstradetreaty.org/att/why.we.need.an.att.pdf Amnesty International. “Guns or Growth? Assessing the impact of arms sales on sustainable development” June 2004 P.4 – http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ACT30/011/2004/en/9183aede-d5c6-11dd-bb24-1fb85fe8fa05/act300112004en.pdf Arms Without Borders. “Why a globalised trade needs global controls”. Control Arms Campaign. P.4 Oct 2006. http://www.controlarms.org/en/documents%20and%20files/reports/english-reports/arms-without-borders Amnesty International. “Compilation of Global Principles for Arms Transfers”. Arms Trade Treaty Steering Committee. P.4 2007. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/POL34/003/2007/en/9b02b99b-d3ae-11dd-a329-2f46302a8cc6/pol340032007en.pdf Buchanan Cate.“Peace agreements, DDR and weapons control: Challenges and opportunities”. IANSA Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue P.2/2006 - http://www.iansa.org/un/documents/Peace-agreements-DDR-weapons-control.pdf Control Arms Briefing Note. “UN arms embargoes: an overview of the last ten years”. March 2006. http://www.controlarms.org/en/documents%20and%20files/reports/english-reports/un-arms-embargoes-an-overview-of-the-last-ten Faltas Sami, Glenn McDonald, Camilla Waszink. “Removing Small Arms from Society- A Review of Weapons Collection and Destruction Programmes”. Small Arms Survey .8 / July 2001 - http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/files/sas/publications/o_papers_pdf/2001-op02-weapons_collection.pdf GenevaDeclaration, Small Arms Survey. “The Global Burden of Armed Violence”. Geneva: Geneva Declaration Secretariat. P.III 2008 http://www.genevadeclaration.org/pdfs/Global-Burden-of-Armed-Violence.pdf Garcia Denise. “Small Arms and Security – New Emerging International Norms”. 2006. Hubert Don, S. Neil MacFarlane. “The Landmine Ban: A Case Study in Humanitarian Advocacy”. P. X/2000 ICRC. “Arms transfer decisions: Applying international humanitarian law criteria — A practical guide”. Annex 3.P.20 May 2007 http://www.icrc.org/Web/Eng/siteeng0.nsf/htmlall/p0916/$File/ICRC_002_0916.PDF Mitsuro Donowaki. “The UN and the Small Arms Crisis: Preparing to Meet the Challenge”. Issue No. 49, August 2000. http://www.acronym.org.uk/dd/dd49/49unarms.htm Parker, Sarah. “Implications of States’ Views on an Arms Trade Treaty”. United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research P.2/January 2008 Parker, Sarah. “Analysis of States’ Views on an Arms Trade Treaty.” P.3 Oct 2007 Prins, Daniël “Engineering Progress : A Diplomat’s Perspective on Multilateral Disarmament”. United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). P.110/2006 Richard Gowan. “The Strategic Context: Peacekeeping in Crisis”. 458/2006. http://www.globalpolicy.org/images/pdfs/0722peacekeepingcrisis.pdf Small Arms Survey, Mike Bourne, Malcolm Chalmers, Tim Heath, Nick Hooper , Mandy Turner, Department of Peace Studies. “The impact of arms transfers on poverty and development, September 2004“ P.10 Small Arms Survey website. “Practical Disarmament”. http://smallarmssurvey.org/files/portal/spotlight/disarmament/disarm.html Small Arms Survey 2003. “Making the Difference? Weapons Collection and Small Arms Availability in the Republic of Congo”P.8 - http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/files/sas/publications/year_b_pdf/2003/2003SASCh8_summary_en.pdf Small Arms Survey, Mike Bourne, Malcolm Chalmers, Tim Heath, Nick Hooper, Mandy Turner, Department of Peace Studies. “ The impact of arms transfers on poverty and development, September 2004” P.8 - http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/files/portal/issueareas/victims/Victims_pdf/2004_CICS.pdf Saferworld. “Making it work: Monitoring and verifying implementation of an Arms Trade Treaty”. P.3/May 2008. http://www.saferworld.org.uk/images/pubdocs/Making%20it%20work%204th%20prf%20%282%29.pdf Tamara Duffey. “Cultural issues in contemporary peacekeeping”. Centre for Conflict Resolution, Department of Peace Studies, University of Bradford. P.142/ 2000 - http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/547177_731202505_784176095.pdf UN A/CONF.192/15. “Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects”. UNDP. “Human Development Report 1994”, UNDP. http://www.un.org/cyberschoolbus/peaceday/facts.asp UNDPKO website. United Nations Peacekeeping. “Home”. http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/ UN General Assembly.“Towards an Arms Trade Treaty: establishing common international standards for the import, export and transfer of conventional arms”. UN General Assembly A/63/334, August 26 (2008). UNNC. UN News Centre. “Ban Ki-moon details plans for restructuring UN peacekeeping, disarmament work”. February 2007 – http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=21601&Cr=restructuring&Cr1 UNOCHA . UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. “Cote D Ivoire: UN sends peacekeepers, but disarmament on hold”. February 2004 - http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/news/2004/02/mil-040229-irin01.htm UNOSSAA. United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Africa. “Disarmament, Demobilization,Reintegration (DDR) and Stabilityin Africa” P.7 2006 http://www.un.org/africa/osaa/reports/DDR%20Sierra%20Leone%20March%202006.pdf UN Security Council. S/2008/258. 17 April. P.6/2008. http://www.un.org/disarmament/convarms/SALW/Docs/SGReportonSmallArms2008.pdf UN Security Council S/2000/101. “The Role of United Nations Peacekeeping in Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration”– http://reliefweb.int/rw/lib.nsf/db900sid/PANA-7DLGMV/$file/sc_feb2000.pdf?openelement USGAO. United States Government Accountability Office. “United Nations Peacekeeping Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate” P.4/ December 2008. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09142.pdf Endnotes 1.) NATO, African Union, etc. 2.) Available from UN Information Centre and UNA 3.) Max Boot. Paving the Road to Hell: The Failure of UN Peacekeeping. Foreign Affairs. March/April 2000. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/55875/max-boot/paving-the-road-to-hell-the-failure-of-u-n-peacekeeping 4.) Committee on Conscience. Burundi Current Situation. United States Memorial Museum. Spring 2008. http://www.ushmm.org/conscience/alert/burundi/contents/02-current/ 5.) Nile Gardiner, Ph.D.The U.N. Peacekeeping Scandal in the Congo: How Congress Should Respond. The Heritage Foundation. March 22, 2005. http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/hl868.cfm 6.) BBC News. UN probes 'abuse' in Ivory Coast. 23 July 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6909664.stm 7.) United States Department of State Travel Warning. December 15, 2008. http://travel.state.gov/travel/cis_pa_tw/tw/tw_915.html 8.) The Haiti Support Group. Haiti News. March 3 2009. http://haitisupport.gn.apc.org/fea_news_index.html 9.) BBC News. UN probes 'abuse' in Ivory Coast. 23 July 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6909664.stm 10.) IBID 11.) Max Boot. Paving the Road to Hell: The Failure of UN Peacekeeping. Foreign Affairs. March/April 2000. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/55875/max-boot/paving-the-road-to-hell-the-failure-of-u-n-peacekeeping 12.) David Smock. On the Issues: Somalia. United Sates Institute of Peace. January 9, 2007. http://www.usip.org/on_the_issues/somalia.html 13.) CNN.com. U.N.: 100,000 more dead in Darfur than reported. April 22, 2008. http://www.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/africa/04/22/darfur.holmes/index.html. 14.) The Heritage Foundation - http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/images/Chart2-lg.gif 15.) United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. “Background note: 31 May 2009”. http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/bnote.htm 16.) United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. “Background note: 31 May 2009”. http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/bnote.htm 17.) Mercycorps. “Millennium Campaign”. October 4, 2005 - http://www.globalenvision.org/library/8/809/ 18.) Council on Foreign Relations, Jean-Marie Guéhenno. “Key Challenges in Today’s UN Peacekeeping Operations” [ Rush Transcript; Federal News Service, Inc.] 2006. http://www.cfr.org/publication/10766/key_challenges_in_todays_un_peacekeeping_operations Appendix Fig A – Some of the issues that outstanding issues that stand as obstacles to the ATT (Parker 2007:3):

Fig B - Some examples of recent Peacekeeping missions and outstanding Issues:

Note: Not only do peacekeeping operations come at a high material cost, but they too come at a high humanitarian cost. The examples above demonstrate how even when deployed under an international set of standards, unprofessional soldiers, usually from developing countries, engage in inhumane behavior, which in turn lays the grounds for further instability. On a further note, even collaboration between numerous organization is a difficult issue (such as the case of former Yugoslavia) - NATO, the EU and the UN carried out operations without a clear system of the chain of command or structural order. Fig. C – The Costs of Peacekeeping14: Fig D- Some examples on UN Peacekeeping Fatalities and operational costs>[15]:

Note: 18 current peace operations directed and supported by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations yield a 2008-2009 total cost of 7,057,751,600 USD16. Now when taking into consideration the fact that: “to ensure improvements in fundamental human needs by 2015 approximately $75 billion (7. 5 Billion USD per year) will be required over the next decade to achieve these eight Millennium Development Goals”17. It becomes apparent that while the world is overwhelmed with raising money to meet annual MDG goals, the United Nations already spends what is required per year to meet the MDGs on UN Peacekeeping Missions. Let aside the philosophical debate in this regard, one must admit that SALW and eventually conflict itself poses a serious threat to overall human security. Although total costs may appear to be alarming, it is important to remember that the annual operating budget for the 18 peacekeeping-related missions is roughly equivalent to one month of operations, U.S. operations, in Iraq—about $5 billion18 Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |