From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 6 NO. 1A Call for Ecologically Informed Policy to Address Sex Work: Evidence From Kenya

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2012, Vol. 6 No. 1 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

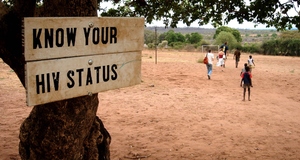

AbstractWith the recognition that sex workers constitute a key population at higher risk for the acquisition and dissemination of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has come an appreciation of the central role that they might assume in policy solutions to the global HIV epidemic. Since then, the activist approach and to some extent, the academic gaze have shifted from mere disease control to a more comprehensive accounting of sex workers’ lives. Policies and strategies for interventions, however, have largely lagged behind. Most interventions treat sex workers as a focal point of an infection network, while the daily realities of women and men who do sex work are often placed on the back burner of analysis.1 Ignoring the totality of sex workers’ lives, in particular their strategies for responding to the risks of their profession, leads to two kinds of problems. First, ignoring economic, political and psycho-social factors potentially jeopardizes the success of existing interventions to reduce HIV infections. Secondly, the indifference to the full ecology of risks – an interconnected set of forces affecting the individual - renders policies and interventions incapable of addressing the myriad violations of sex workers’ basic human rights to health, well-being, and security of person. Disease control policy that is informed by a more holistic analysis of the risks and needs of sex workers will both maximize policy effectiveness, and expand policy scope to include upholding the basic human rights of sex workers. This paper uses interviews with female sex workers in rural Kenya to argue for a more holistic analysis in research and policy agendas for understanding risk ecologies that drive sex workers behavior, and realizing the human rights of sex workers worldwide. An Ecological Approach to Forces on BehaviorTheories from social psychology, social epidemiology, and public health converge on the idea that understanding and influencing individual behavior hinges on an appreciation of the motivating and restraining forces acting on each individual in her immediate environment. Such ecological approaches indicate the psychological, socio-economic, cultural, and political factors that drive behavioral patterns. Advocates of ecological approaches have astutely argued that behavior change interventions that ignore this wider ecology of factors will dilute their efficacy.2 Instead, they argue change is produced by altering the constellation of forces acting upon the individual.3 With the emergence of HIV and AIDS worldwide, the push for the inclusion of ecological factors in assessing risk situations has gained renewed significance. It is precisely a shift towards an ecological approach that must be advocated within the policy realm of interventions targeting sex workers. Successful interventions will address the contextual risk factors that motivate behavior, rather than assisting sex workers in coping with a context that has not changed. Ecological Risks for Sex Workers in Rural KenyaStudies of the roots and nature of sex work have revealed a complex network of harmful ecological forces and risks far beyond STIs: cycles of financial instability, physical, psychological and sexual abuse, a lack of legal protection, and abuse at the hands of police.4 Ninety-nine sex workers in Nakuru, Kenya, discussed these risks in interviews conducted between August-October 2010. The results contribute to the body of evidence from around the globe by providing a portrait of the quotidian and long-term challenges as well as the larger structures of inequality driving sex workers’ behavior. Allowing their insights to inform future policies and interventions has the potential to enhance the larger public health response. Background CharacteristicsOn the micro level, understanding the primary pathways leading into the sex work industry can help explain ongoing motivations to remain in the business and point to entry points for prevention efforts. A sex worker’s demographic background and household dynamics can determine her dependency on the sex trade. In this cohort of female Kenyan sex workers, between 19-42 years old, 20% did not finish primary school, and 27.7% completed secondary school. Most women indicated that their poor educational qualifications exacerbated their difficulties finding a job in the formal sector, rendering sex work their only viable option to generate income. As other studies have suggested, patterns of gender bias in access to formal education can be a compounding factor in the network of social vulnerabilities that drive women into sex work.5 Children constituted a major concern in most women’s lives. Women commented on their responsibility to provide food and school fees for younger members of the household, including for up to 7 children of their own. Most confirmed that this economic necessity sways their daily decision-making in whether or not to see a client or to engage in risky but better compensated sex. Nearly all women identified themselves as the head of their household, and although forty-one (63.1%) indicated that they currently had a stable, intimate, non-paying partner, not one woman stated that she is married. Marriage status emphasizes the socio-economic context of their situation: marriage is a Kenyan woman’s source of respect and financial security. Studies of the roots and nature of sex work have revealed a complex network of harmful ecological forces and risks far beyond STIs In the rural areas particularly, patriarchal structures dictate a traditional division of labor, where the husband ordinarily generates income and the wife is expected to fulfill household duties. Single-parent, women-headed households are plagued by obstacles to women’s ownership of property entrenched in the law and an unfavorable position in the labor market, which contribute to economic deprivation.6 Economic incentivesThe overwhelming evidence of financial deprivation as a major reason for entering sex work underlines the difficult economic dimension of the profession. Many women indicated that the death of either a parent or a partner pushed them into financial problems. For others, a sudden or unplanned pregnancy deprived them of monetary support from either their partners or parents, and led to destitution. In some instances, the onset of pregnancy forced participants to leave school, forgoing their education, while in others, the consequences of raising a child exacerbated financial insecurity. Life-circumstances and lack of economic opportunity interact with cultural notions of child-rearing, the traditional importance of marriage and geographical conditions to intensify economic marginalization of women in rural Kenya. A number of participants mentioned a combination of the above-mentioned factors, for example: “I was abused by my stepmother, got married, divorced, and then fell pregnant. I tried to commit suicide, but then someone introduced me to sex work and suddenly, I could make money.” (Alice,7 35 years old) However, early research into sex work lacked an economic perspective on the industry. As William-Navarro aptly criticizes, economists’ initial proclivity to consider sex workers’ ‘illicit’ behavior as largely irrational prevented researchers from considering monetary incentives and disincentives driving individuals’ choices in the sex trade.8 The resulting lack of data on this economic dimension “helped feed policies aimed at criminalizing sex work or rehabilitating sex workers, rather than at addressing the constraints and needs of sex workers, or the larger context in which they work.”9 HealthSex workers face a plethora of health risks on a daily basis. When prompted for their health concerns while at work, 75.4% of the women stated that they are concerned about sexually transmitted infections (STIs), while 32.3% mentioned pregnancy, and 12.3% violence at work. While general consciousness of STIs has risen in recent years due to community-wide awareness efforts, sex workers’ recognition of violence as a violation of their rights and as a danger to their own health has lagged behind. Almost half of all participants (44.6%) indicated that they have experienced between one and six unwanted pregnancies, of whom about a third (35.5%) had at least one abortion. Many of the abortion procedures were not done at a health facility because of legal or financial constraints. Such unsafe procedures often led to various complications during the process, including excessive bleeding, pelvic and abdominal pain, often lasting many days after the abortion. Insufficient knowledge of and access to a variety of contraceptive methods exacerbates the rates of unwanted pregnancies and subsequent complications. Finally, the constant threat of physical and sexual abuse can render sex workers vulnerable to psychological distress and trauma: A few participants admitted they had attempted suicide, and to their concomitant drug use. Many women mentioned using alcohol to deal with the daily ordeal of sleeping with their clients. PracticesSex workers’ income is inherently dependent on their negotiation power and ultimately the clients’ agreeableness. Women in this study reported that in addition to conventional intercourse, some offered oral sex, body massage, and various sexual positions. Their lowest rate charged for any of the services above is KSH 30 ($0.40) and the number of customers varies between one and ten a day. While every single participant indicated that she prefers using a condom when having sex with a customer, the majority stated that customers offer more money for unprotected intercourse, an economic benefit the women by and large cannot reject. Participants’ most-cited concern while out looking for customers was violence or abuse by a customer (58.5%), followed by fear of harassment or arrest by the police (49.2%). In the past month, the majority of women had experienced a physically violent customer (71.9%), and more than half had been raped by a customer (58.7%). Additionally, a large proportion of participants experienced a customer leave without paying for their services (77.4%), or a combination of the above. While the women’s involvement in sex work is, in its most basic form, a struggle for financial survival, many described that the pervasiveness of violence perpetrated against them turns their condition into a struggle for safety, too. As one woman put it: “I don’t like wearing high heels because I cannot run away if I have to. And I do not wear scarves because customers might strangle me. Some customers tell you that you cannot leave; they keep you. Sometimes there are many of them who have sex with you even though you do not want to.” (Joyce, 35 years old) PoliceThe participants’ collective insights revealed a pattern of violence, discrimination, and exploitation on behalf of policemen towards the sex workers. Most participants stated that they do not feel safe to go to the police if they have a problem with a customer (64.5%), citing fear of arrest (89.7%), harassment (55.2%) and rape (31.0%) as reasons for their concern. Many women explained that the police “demand sex in exchange for (their) freedom.” When an officer demands unprotected or risky intercourse, the sex worker makes her decision not only based on an increase of her income, but to negotiate her basic freedom and to forego violence. Furthermore, participants described that carrying condoms can become a risky predicament since some policemen use the existence of condoms as evidence for charges of commercial sex. This type of policing practice is detrimental to efforts seeking to curb disease transmission, as well as it considerably hampers sex workers’ autonomy to protect themselves. Laws and Legal Enforcement PracticesOn the macro level, legal policies and local enforcement practices are potentially strong determinants of health outcomes.10 In effect, while selling sex is not illegal in Kenya, soliciting or abetting the sale of sexual services and knowingly living on the earnings of commercial sex are illegal activities according to the Penal Code. Due to fear of arrest, sex workers report fewer human rights violations, particularly violations of a sexual nature, including incidents occurring at work and in their private life.11 Since condoms are frequently used as evidence for commercial sex the prospect of accusation lowers women’s willingness to carry and use condoms, rather than reducing the amount of women who knowingly live on the earnings of commercial sex.12 On the one hand, written laws on sexual abuse and rape dictate what constitutes a violation and ultimately, who can report one. On the other hand, local practices determine who will listen and whom will be believed. The sex worker makes her decision not only based on an increase of her income, but to negotiate her basic freedom and to forego violence. Condemning the possession of condoms puts the health of both sex worker and customer at risk and directly fuels the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). A current hurdle to eliminating this practice is the similarly poor acceptance of condom use outside of the industry: almost half of the participants (47.6%) stated they do not use a condom with their intimate partner. Similarly, a study of men’s attitudes and practices regarding sex in Thika, Kenya, showed that although 85% believe that sex is vital for reasons other than procreation, condom use with spouses and girlfriends is low at 13% and 26%, respectively.13 The negative, exclusive association of condoms with sex work fuels this resistance to protected intercourse in other sexual relationships. Finally, both the official laws and the local legal enforcement practices have a significant impact on community values and can thus hamper or promote discrimination and stigma against sex workers. The code of conduct exhibited by the local police force can be a model to members of the community. The level of impunity with which police perpetrate violence and abuse against sex workers affects the community through “social control strategies,” which increase stigmatization of sex workers.14 StigmaStigmatization by their communities and the self-internalization of stigma are catalysts of myriad effects on sex workers. Sex workers are often considered to be a particularly vulnerable sub-group of HIV and AIDS-related targets of stigmatization, even if individuals are not themselves HIV-positive, since a “double stigmatization” can occur, where “female sex workers are marginalized even within an already lower prestige in-group of women in general.”15 In Kenya, police forces and other deviant customers abused present inequalities to validate their own social standing to the detriment of the individuals dependent on the sex trade. Equally discrediting sex workers’ value in society is the regular perpetuation by mass-media reinforcements of negative stereotypes of sex workers, for example in national newspapers.16 This can lead to internalization of stigma imposed on female sex workers, often translating into a contrived self-perception that can discourage women from claiming their basic rights, and can directly influence their health-seeking behavior.17 Policy ConclusionsListening to sex workers’ insights reveals the manifold layers of barriers to their individual behavior change, which will prevail if the contextual factors around them remain unaltered. The following recommendations should inform future policy and intervention design to ensure disease control efficacy and to realize sex workers’ basic human rights. Laws and Legal Enforcement PracticesGiven the current interaction of the laws on commercial sex and the implementation of these policies, the Kenyan government must review the efficacy and negative effects of its legal framework. In its current permutation, it has deleterious effects on the lives of Kenyan citizens who are involved in the sex trade, especially female sex workers, and it simultaneously hampers efforts to address HIV and AIDS in the communities. Furthermore, the abuse of legal enforcement practices to elicit gratuitous sexual services and the impunity of genderbased violence perpetrated by authorities need to be addressed. Workshops and trainings for the police should be held to establish standards of conduct that clearly condemn such violence given its detrimental effects on the individual lives of sex workers and the larger community. Mechanisms to monitor closely the enforcement practices of police officers, including credible threats from superiors to impose sanctions such as docked pay and discharge from service, can go a long way in eliminating procedures that seriously compromise sex workers’ security and autonomy. Under no circumstances should condoms be used as evidence to prove commercial sex. Normalizing condoms as a form of protection will underline the importance of safe sex in the industry and within other intimate relationships, and encourage sex workers and their customers to obtain, carry, and use condoms. Health ServicesProviding adequate health services to sex workers and their families is imperative to countervail their heightened vulnerability to STIs, poor psychological health, and various forms of violence, and to realize their basic human right to health and well-being. This must include access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services, primary health care, psychosocial support, and specialized responses to rape and other forms of genderbased violence. Given sex workers’ economic instability, this care must be made affordable. Finally, local health service providers need to be educated on sex workers’ comprehensive ecology of risks, with a special focus on their sexual, reproductive and psychological health needs. Direct Aid to Sex WorkersEducation of sex workers about their own health, rights, and opportunities must be continued and expanded. This should include information on the benefits of using protection with non-paying partners as well. The system of peer education serves the dual purpose of putting an individual sex worker in a position where she perceives herself to be valued, while at the same time multiplying the reach of the educational training devoted to her by providing this to other sex workers at a low cost. The knowledge and responsibility bestowed on the peer educator has the potential to help revitalize her self-efficacy and validate her utility to the community. Further, workshops on gender-based violence must be expanded. These workshops should include information about the Kenyan laws on sexual harassment, assault and rape, sex workers’ rights to report such violations, and procedures for reporting both in a health facility and at a legal authority. Including the police in such efforts can be essential to their effectiveness. Support groups can facilitate solidarity amongst sex workers with numerous positive outcomes. They can provide a safe outlet for the psychological stress of sex work and encourage cooperation instead of competition. Groups should facilitate the mobilization of sex workers around their needs and advocate for sex workers’ inclusion in program and policy-making. Finally, economic support of sex workers can have a direct impact on the spread of disease. Based on the observation that sex workers lack basic formal and informal means of coping with their vulnerabilities, providing them with mechanisms to cope with such risks could considerably improve sex worker welfare, and curb the spread of HIV.18 Community-level AwarenessAt the community level, first, clients or potential clients of sex workers should become the focus of disease prevention efforts. That is, men should be held more accountable for contributing to the transmission of disease in the sex trade. Since the decision to use protection to minimize infections lies largely with male customers, men in the community should be educated especially on the importance and benefits of protection. Key client populations at higher risk, such as truck drivers, must be particular targets. These drivers are highly mobile, travel long distances, and spend long periods of time separated from their families in conditions conducive for engaging in multiple sexual transactions while in stop-over towns along the way.19 A review of interventions for truck drivers suggests that efforts to increase sexual health-seeking behavior and condom use are more effective than those seeking to reduce the number of sexual partners.20 Second, the wider community must be educated on the realities of daily sex work to effect change with regards to hostile attitudes. Sensitization campaigns seeking to eliminate stigmatization of sex workers must stress, amongst other things, the detrimental consequences of the tacit acceptance of gender-based violence. To this end, religious leaders could be mobilized to foster respect for all citizens amongst their respective communities. ResearchResearch into any of the discussed forces and risk factors will shed further light onto how best to address them, and to monitor and evaluate such interventions. For example, studies could explore the exact determinants of police behavior towards sex workers, the impact of negative attitudes and arrest quotas, and specifically how sex workers tackle police interference. Similarly, more research is needed on the origins and role of stigma and how to best combat cycles of stigmatization and discrimination. Moreover, research is needed to evaluate the impact of the interventions suggested above, including methodological designs that allow for causal inference, adequate indicators and long-term follow-up, to establish a record of best practices and to facilitate evidence-based policy making in the future.21 Endnotes

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |