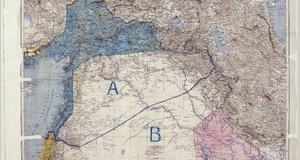

Featured Article:The Islamic State Healthcare Paradox: A Caliphate in CrisisSuccess or Caliphate Fantasy? Straddling Between Two Competing NarrativesTo effectively analyze a group as advanced as IS, I digress from specific cherry-picking argumentations and rather holistically examine those who both claim and defame the model upon which The Islamic State operates. This is one side of the narrative—that of those individuals who praise the model. These are individuals who believe that IS’s ability to deliver services and regular paychecks for professionals such as doctors make them a better administrative body than the Iraqi or Syrian governments (Friedland). In the areas of Communications, Electricity, and transportation infrastructure, the Islamic State’s work in cities like al-Raqqab have been praised as noteworthy and successful (Halevy and Blank). Rather than functioning as a mere terrorist network, such as IS’s predecessors or peer terrorist networks like the Tablian, al-Nusra Front, and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, IS has been able to take over and subordinate all existing government institutions to the IS bureaucracy. In healthcare, IS has overseen large health campaigns, such as mass polio vaccinations and grants for individuals suffering from cancer or infectious diseases to go to the Mosul hospital, “said to be one of the most important cancer treatment centers in the Middle East (Umaña).” Moreover, IS is acting as a conduit for foreign aid distribution in order to effectively support struggling communities and win support.The other narrative is far bleaker, but not necessarily diametrically opposed to the first one. This narrative argues that IS has managed to replace the state with sufficient results in the fields of justice and education, but “one of the organization’s major policy failures lies in the health sector (Alami).” The public clinics are reserved for the impoverished, and hospitals suffer from power shortages and resource undersupplying. Their abusive treatment of female personnel in Mosul Hospital triggered a strike in August 2014, and, as a result, IS was forced to compromise and tone down the severity of certain restrictions (Alami). In sum, IS affords the highest quality treatment for its own fighters, and civilian hospitals lack the high-end equipment found in secretly located hospitals for IS fighters (Alami). As a result, prices for medicines and services have escalated dramatically across the caliphate. The Jihadists have been forced to smuggle in basic medications for distribution to hospitals and health clinics under its control, but citizens generally purchase the drugs themselves for upwards of triple the normal price (Cunningham). Shortages of wheelchairs and high-end technologies have rendered long-term treatments and care for paraplegic and elderly patients impossible, among other treatments (Cunningham). With the advent of the United States-led coalition bombings, hundreds of IS fighters have been regularly injured, and doctors have since been ordered to use blood for transfusions solely for fighters; civilian patients have been ordered to supply their own blood by contacting donors privately (Cunningham). With dire circumstances, The Islamic State recently issued an ultimatum to physicians that had fled to return to their work or have their property seized (Cunningham). These actions have collectively compromised the quality of care for civilians, ultimately alienating and stigmatizing patients without proper access to medical resources. By enforcing rigid, segregationist, and gendered divides between physicians, the efficacy of hospital management has declined, as males cannot treat females, and females cannot treat males unless given very specific permission. As consolation, the terrorists maintain the health system by compromising on certain measures for women and men. For example, IS permits a single hospital employee to travel to a city hospital controlled by the Kurds in order to acquire cash from government-approved banking facilities; likewise, IS has begun allowing certain female patients to see male physicians for concerns such as a broken arm (concerns that do not relate to sexual organs) (Cunningham). I now collapse both narratives framed by discourse into the same spectrum. An appraisal of caliphate’s performance across all areas reveals decent rankings for nearly every measure except for healthcare, which was given a failing 5/10 ranking (Mecham). The lives of civilians whom IS understands it must gain support from are deteriorating largely due to the implications of haphazardly applied IS decisions. If IS rationalizes its behavior appropriately, it would realize as an organization that its mission and its implementation of its ideological agenda are fundamentally opposed to one another. The rhetoric is pretty, in that the organization is “providing social services” and “promoting its own health architecture,” but the voices on the ground paint a very grim portrait that indicates that by all standards, IS-run healthcare is an utter disaster that is unnecessarily complicating the refugee exodus and the pre-existing health crisis in Syria and Iraq. So now I must ask: what are IS’s motives? What is their psychology on healthcare? Rationalizing The Islamic State Psychology and Modus OperandiI demonstrate how IS action and rhetoric are inherently contradictory, and I hope to justify exactly why that is. Foremost, on what agenda does IS operate? The militants’ public statements seem to indicate that their principle of statehood is predicated on Foucault’s notion of biopower—a regulation of life and death in order to provide welfare for the common good. I argue that IS fundamentally rejects the concept of biopower in practice; rather than basing claims of power on collective prosperity and function, IS bases all societal proceedings on its self-declared understandings of religion and religious laws. Whereas terrorist organizations are generally motivated by an aspiration to engage in armed struggle with the West, acquire territory, become financially prosperous, and instill fear for control purposes, IS uses all these aforementioned tactics as means to an end of firmly entrenching religious norms in all civilian structures. That is precisely why one finds IS acting haphazardly—its intentions are not practical, but they are adherent to a guidebook, and that guidebook is an ideological-political religion. The torture of women, children, and other people feeds into the IS terrorist conviction that one must eliminate infidelity in Islamic society, and more specifically, IS’s practice of Islamic law and culture. This is surprising, then, for the Qur’an’s preaching on health is extremely positive and peaceful. According to Islamic scholars, health is considered one of God’s blessings, for “He [Allah] formed humans both beautifully and in an environment of general well-being (Qur’an 40:64).” The hadith, which records the sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, regards health as a blessing from God, as Mohammed stresses that personal well-being incorporates physical and spiritual cleansing prior to prayer or other similar practice (Waugh). Former Islamic Caliphates have endorsed these messages on health. The Abbasid caliphate, which ruled from 750 to 1258, was based on “multiculturalism, science, innovation, learning, and culture, in contrast to IS’s violent puritanism (Diab).” It was largely following the wars of the 19th Century and the failures of Middle Eastern governments to deliver welfare with the imposition of authoritarian rulers that set the initial framework for power vacuums over the past fifty years that allowed such instability to slowly grow. Given this knowledge, where does IS acquire its religious justification? How can any faithful Muslim find commonality with brutality when the Prophet and Allah both plaudit the power of faith in promoting peace and welfare? The Islamic State has one ideological foundation that serves as its driving force: the 14th Century Scholar Ibn Taymiyya’s teachings of Salafism (Barrett). The Salafist interpretation of Islam “demands the harsh and absolute rejection of any innovation since the times of the Prophet…diversion from puritanical precepts that they [individuals] draw from a literal reading of the Qur’an and the Hadith is blasphemy, and must be eradicated (Barrett).” Salafism thereby rejects Sufism, Shi’ism, and any other interpretation or religion in favor of uniting the Muslim world under “truly Islamic rule” and “fulfilling God’s desires.” Rationalizing every IS action under a lens of Salafism beings to put everything into perspective. The Islamic State sees no harm in executing physicians or other related healthcare providers because its aim is to create a healthcare apparatus that serves the interests of its fighters—this is to ensure that it has the necessary power to enforce its agenda, quell resistance among dissatisfied Sunnis, and prevent backlash from materializing in the form of rebellion—and minimally serve the population as to minimize dissidence and perform as much damage control as possible. The Islamic State functions in a similar manner as an ineffective totalitarian dictatorship, but its foundations are derived from pseudo-religion and are thereby neither secular nor religious. Insertion of this pseudo-religion into daily life makes IS an apathetic organization, incapable of empathizing with human emotions and thereby incapable of humanitarianism pursuits. Does IS respect healthcare? Yes. Is IS attempting to fabricate an apparatus that reflects that respect and a broader need for healthcare given the collapse of healthcare apparatuses in Syria and Iraq? Yes. Is the IS psychology on health clear given the harsh, conservative amalgamation of Salafism and civil society? Absolutely.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Political Science |