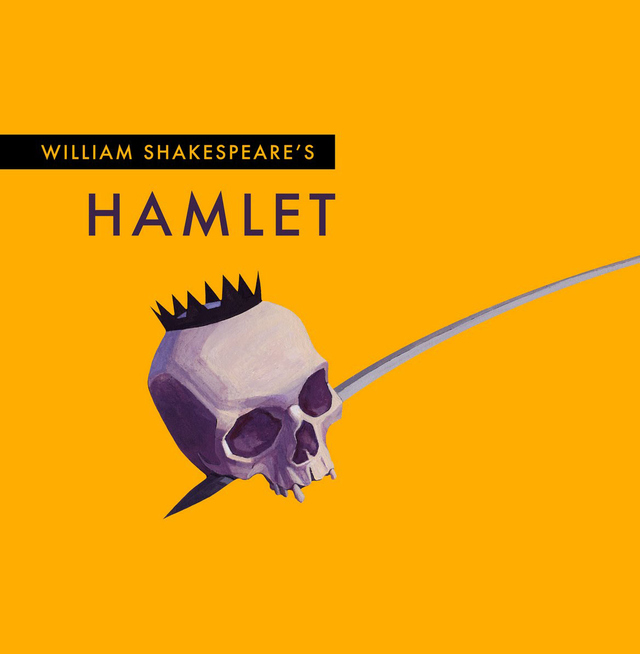

Polysemic Language, Democratization, and the Empowerment of the Body Politic in Shakespeare's Hamlet

By

2015, Vol. 7 No. 06 | pg. 1/1 AbstractIn William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Prince Hamlet’s polysemic language raises the theme of empowerment of the body politic and, ultimately, the notion of democratization. Through an analysis of Hamlet’s speech, particularly in response to King Claudius, this paper suggests that a democratizing percept is intrinsically rooted in this work and further elucidated upon careful consideration of Ranciere’s The Emancipated Spectator. By exploring Ranciere’s notion of active engagement with the “third thing,” this paper highlights the democratic politics that encompass Shakespeare’s text. In William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Prince Hamlet’s polysemic rhetoric empowers the body politic and endorses notions of democratization. As a result, Hamlet appears to jettison the institution of monarchy in favor of democracy. In effect, Hamlet’s language encompasses the realm of political thought because, through his words, citizens are elevated to equal footing footing in relation to the king. Through polysemy, the body politic, reader, and spectator are exhorted to “play” with the “third thing,” or this interpretable, exterior medium. By grappling with their respective intermediary bodies, namely law as well as death, text, and theatrical performance, those who “play” can uncover meaning and appropriate a sense of order in their own particular contexts. This spectacle emphasizes the experience of the third thing with respect to the recipient, as the goal is not to penetrate through the language to one specific interpretation promoted by the author or king, but, rather, to excogitate upon the linguistic nature of the object and its multivalence and expansive potentiality. Furthermore, Hamlet’s polysemic language ultimately facilitates interpretations of equality and empowerment through the evocation of death, thereby implicitly championing democratic politics. In Act 4, Scene 2, of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Prince Hamlet’s rhetoric oozes with polysemy, as his words can be interpreted as having a multiplicity of meanings. In particular, such a polysemic phrase is evident when he paradoxically affirms, “The body is with the King, but the King is not with the body. The King is a thing – […] Of nothing” (Shakespeare, 292). The togetherness of the body and the king may imply that the king can exercise his authority and enforce legal doctrine in his own body and right. This interpretation seems to buttress the notion that the implementation of the law is inherently tied to a tangible thing – in this case, the king’s body. However, the latter portion of the quotation reflects a sense of detachment between the offices of the king and his own body, connoting that the king’s dictates can persist irrespective of his existence. Accordingly, once the king dies, law and order can continue to regulate citizens’ lives. Ironically, the king himself, thus, appears to be relatively unimportant in ensuring the maintenance of order in society. Consequently, the king can be perceived as being somewhat passive in his role as executor of power, with the body of laws functioning as this external “third thing” situated somewhere between the king and his subjects. In addition, just as a reader grapples with the text or “third thing” that the author has labored to produce and offer to his readership, the body politic can grapple with the body of law as this “third thing,” or an imperishable medium through which they can derive meaning and stability in their lives. The king’s ultimate passivity mirrors the ultimately passive nature of the author, whereas the body politic’s active role in interpreting laws aligns with the reader’s dynamic role in parsing and analyzing the text. Once the author translates his thoughts into words on the page, he surrenders any control that he may possess over enforcing its meaning. Similarly, though the king has the power to implement the body of law, once codified, he, too, capitulates to the vagaries of polysemy, which enables and ennobles the body politic to interpret legal doctrine as they will. The king no longer has exclusive power over legal doctrine, as that power is transferred from the ruler to the “third thing,” or the body of law itself. The body of law derives its power from the very fact that it is open to various interpretations, and the body politic can interpret and translate those percepts into a system of morality for themselves that is peculiar to their social context. The power of interpretation, essentially polysemy, allows the body politic to specifically tailor and apply the word of the law to their particular situation in order to foster order and abide by the law within their sphere of influence. Thus, given that body politic retains the capacity to subsume the law into their own morality through interpretation in order to perpetuate justice and order in society, the sovereign or king assumes a relatively limited, functional role – that is, he ostensibly becomes unnecessary. Therefore, interpretation of the law can be deemed fluid and grounded in the body politic. Ultimately, the members of the body politic are the de facto guardians of the law, not the king. Accordingly, the king is rendered relatively impotent, in a virtual figurehead role. Prince Hamlet’s aggressive polysemy, in effect, degrades the role of kingship in general, as he intimates that a degree of order can endure in society even absent a supreme sovereign. Essentially, order can exist without the sovereign, and, to be clear, Hamlet echoes this notion of monarchical superfluity when, as above, he specifically says, “[…] the King is not with the body. The King is a thing – […] Of nothing” (Shakespeare, 292). The assertion that the king is “of nothing” connotes that his reign is not crucial for the perpetuation of order in society. If Hamlet had described the king as being “of something” or “of the body,” only then could it be argued that his role in relation to the body politic were not trivial but, rather, quite important in contributing to societal harmony and the common good of the body politic. However, given his deliberate diction, Hamlet, instead, appears to sanction the model of democracy, as one can purport that an entrenched ruler or lawgiver is unnecessary to ensure that the citizens take ownership of the law. Thus, Hamlet appears to be overturning the very institution of monarchy, supplanting it with a liberating system of democracy that emphasizes the active role of the body politic. The quotation’s aforementioned addendum, namely “of nothing,” effectively intimates that the king ultimately possesses no authority over the observance of the law, as that translation is the province of the minds of the subjects. In effect, he is not king or ruler over the interpretation of legal doctrine. Thus, he is tacitly king of “nothing,” given his lack of prehensile control over citizens’ impressions: his sway is attenuated by the subjects’ interpretational experience in and of itself, which is a function of their relationship to this “third thing.” Holistically, Hamlet’s polysemy evinces the supreme importance of the body politic, thereby underscoring the school of politically democratic thought. Ranciere’s notion of the “equality of intelligence” redounds to this paradigm of democratic empowerment, as he suggests that neither the author schoolmaster nor the reader or pupil possesses a superior knowledge of the “third thing” or intermediate. Specifically, Ranciere states that the schoolmaster does not impart a form of knowledge to his pupil but, conversely, encourages his pupil to traverse the vast expanse of knowing and seeing, essentially to actively push beyond his own intellectual bounds. In Ranciere’s aforementioned example, rather than bestowing exterior, interpretable knowledge upon the pupil through the medium of language, or “third thing,” the pupil can survey the world around him for himself, fashioning it into the framework of his own particular story. In this sense, Ranciere wholeheartedly eschews the idea of an unequal, hierarchical relationship and replaces it with a thoroughly democratic and empowering sensibility. Ranciere’s views can be systematically transposed onto those of Hamlet in the realm of political ideology, as subjects, similar to pupils, can readily take the “third thing,” or the law, into their own hands and apply it to their unique contexts. In essence, the body politic should dare to think and possess the courage to employ their own reason. Hamlet endorses the model of galvanized citizens, encouraging the idea of the body politic actively exercising their capacity to play with the “third thing” to resonate widely throughout society. Playing with this “third thing,” otherwise known as the laws, inevitably enables translation, thereby permitting the body politic to freely express their tendencies, personalities and interests, which may not align with those of the king. Thus, Prince Hamlet’s polysemic rhetoric entreats not only readers but also the body politic to muster the courage to think critically for themselves by wrestling with this “third thing” rather than blindly submitting to the author or king, respectively. This vein of democratic thought invites a torrent of expressive voices that speak truth to power and bolsters the significance of the body politic in relation to the king within society. The body politic can efficaciously “play” with the law and adhere to it by adapting reason to their application of this “third thing,” essentially conforming this legal doctrine to their realm of existence. This view seems to reflect Hamlet’s notion of empowerment of the body politic – a considerably democratic idea – as freedom and happiness appear to be viscerally grounded by interpretation, subject to the body politic’s capacity to think and reason. Thus, one can reasonably construe that kingship and authorship are transcended by the active role of the body politic and reader, respectively, within their social constructs. The active nature of both the reader and the body politic reduce the author and king, respectively, to passive forms that are neither linked to the “third thing” nor its interpretation. Accordingly, Hamlet’s rhetoric veritably suggests the supremacy of democracy over the institution of monarchy. In Act 4, Scene 3, Hamlet, by saturating his text with the potential for polysemy, evokes death in order to champion democratic ideals. Hamlet specifically achieves this end when he both comically and elusively responds to King Claudius’ inquiry regarding the whereabouts of chief counselor Polonius’ body. In particular, Hamlet retorts in an interlocutory fashion, “Not where he eats, but where he is eaten. A certain convocation of politic worms are e’en at him. Your worm is your only emperor for diet. We fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots" (Shakespeare, 20-23). In this passage, Hamlet’s polysemic language allows for the interpretation wherein being “eaten” signifies dying. Hamlet implies that, by fattening other animals in order to feed themselves, people, in so doing, inadvertently fatten themselves for their posthumous consumption by worms. Holistically, Hamlet insinuates that all humans eat and, one day, will be eaten after death. This quotation presupposes death, as the phrase, “we fat ourselves for maggots,” suggests that men ultimately die and maggots feed upon their decaying corpses. Therefore, Hamlet’s polysemic language implies an absence of being via consumption. This notion of consumption in the form of death invokes Ranciere’s Emancipated Spectator, as the act of eating reflects spectatorship. According to Ranciere, once the actor performs the play, he becomes absent in the sense that he relinquishes control over the interpretation of his theatrical performance. The legal doctrine and performance alike are rendered “third things,” entities entirely susceptible to consumption and interpretation by the body politic and the spectator, respectively. Figuratively speaking, the spectator consumes the theatrical performance by digesting and breaking down the language of the play, thereby actively interpreting this “third thing” for himself. This percept of consumption is evinced not only in the realm of theater but also in the realm of democratic politics. Essentially, the aforementioned absence of being is reflected in the role of kinship when the king dies or becomes “of nothing,” as previously stated by Hamlet. Ultimately, with regard to political sphere, consumption in the form death facilitates polysemy because once the king is dead, he has no control over interpretation over the legal doctrine by the body politic. Similar to the situation regarding the king, when an author is not physically present to elucidate the meaning of his text to the reader, opportunities for interpretation, known as polysemy, arise. In effect, the capacity for a multivalence of meaning considerably increases. Every text an author writes serves as a memento mori to be interpreted by posterity. Even while an author is living, he is dead, or absent with respect to the text that he has produced. The author experiences a total loss of authority after putting his words onto paper, and this complete lack of power parallels both the king and the spectator’s absences of authority. Through consumption of theatrical performance, the spectator assumes the role of active interpreter. Upon further excogitation of this active role, one can construe a veritable degree of agency associated with the spectator as he wrestles with this “third thing,” or the theatrical performance itself. The body politic in society possesses a similar sort of agency, in so doing, only further redounding to the notion that Hamlet’s ironic deployment of polysemic language represents democratic politics. In short, this newfound agency directly aligns with democratic political ideals, as democracy flourishes through the agency and power of the demos. Hamlet’s polysemic language champions the notion of equality attained posthumously, implying a degree of democratization as men are “eaten.” Hamlet principally contends that death serves as a vehicle through which men can be integrated into the “demos,” or the people, as death is the ultimate equalizer and unifier of humanity. Quite literally, it is by death that men can become grounded in equality. Hamlet veritably insinuates that the act of being eaten by worms can be equated to democratic ideals devouring and, accordingly, obliterating the monarchical framework. Hamlet’s aforementioned “convocation of politic worms” can be inferred as representing the demos, or body politic. The worms are described by Hamlet as consumptive machines, purportedly in order to evoke the image of the body politic consuming, digesting, and subsuming the laws, or this exterior “third thing,” into their realm of existence, such that they exist wholly separate from the king and entirely in the hands – or, quite literally, in the bellies – of the demos. This visual serves to buttress democratic political precepts and evoke notions of democratic empowerment. In essence, Hamlet’s polysemic language invokes democratic politics. Furthermore, through Hamlet’s polysemic language, death’s ability to unite individuals into a cohesive amalgamative unit permits a politically democratic order to transpire – one that can evolve through the shared experience of death. Death appears to align itself directly with the laws that govern society and the knowledge that lies exterior to Ranciere’s schoolmaster and pupil, as each can be considered a “third thing” through which individuals can experience and interpret. Consequently, Hamlet’s polysemic language seems to espouse democratic politics by firmly entrenching that, by grappling with death, or this “third thing,” individuals unite into a phalanx of sorts, uniformly equal in its composition. The ideals of democratized society are ever so bolstered by the interaction of individuals comprising the body politic with this “third thing.” In essence, citizens attain equality in relation to one another by interacting with this “third thing,” namely, death. In addition to a sense of equality achieved through death, a sense of agency is achieved through the experience of death. In particular, these “politic worms,” or members of the body politic are imbued with agency upon dying, as they actively participate in effecting equality, a purely democratic ideal. This active role is particularly evidenced when Hamlet states, “We fat all creatures else to fat us” (Shakespeare, 22-23). This notion of “fattening” creatures or being “fattened” by others speaks to the idea of continual agency via consumption and decomposition through digestion – in essence, a sense of breakdown, otherwise known as death. In effect, just as the body politic exercises their agency through interpretation of the law, they may similarly adopt an active role in acquiescing to death and its attendant undertones that espouse equality. Thus, this agency and inextricable involvement in one’s death can be construed from Hamlet’s language, thereby serving to further strengthen democratic thought and evoke aspirations towards democratic politics. Finally, the process of death, inferred through Hamlet’s polysemic language, ultimately thrusts agency upon the individual, in so doing, reflecting ideals of democratic politics. The equalizing capacity for experiencing this “third thing” called death serves as the sine qua non for democracy, and this capacity, by virtue of the agency it imparts to citizens, enables empowerment to occur. In effect, owing to this sense of agency afforded through the experience of death, the body politic appears to be inculcated with a surge of empowerment. Ultimately, by imbuing the body politic with blatant puissance, Hamlet’s polysemic rhetoric encourages enlargement of the role of the body politic in relation to the king within society. ReferencesRancière, J. (2014). The Emancipated Spectator. Verso Books. Shakespeare, W. (1904). The Tragedy of Hamlet. University Press. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |