Slavery and Religion in the Antebellum South

By

2011, Vol. 3 No. 01 | pg. 1/1 For many decades, scholars have debated the importance of religion in helping slaves cope with the horrible experience of slavery in the antebellum South. However, the way they treated the subject differs and the conclusions they reached are varied. From the early 1920s through the 1960s, the accent was put on the variety of religious traditions and rituals of the antebellum Southern slaves, but without them receiving the credit for these traditions, which were considered as being adaptations of European beliefs and rituals. Later on, in the 1970s and 1980s these traditions are considered as actually having been weak among the Southern slaves, replaced by Christianity, which, however, was adapted by the slaves according to their needs. In the 1990s and 2000s, the subject of slavery and religion is much more specific: for example, scholars focus on the role religion played in helping slave women cope with slavery, or the role religion played in helping elderly slave women cope with the “peculiar institution.” Nonetheless, whether the scholars’ bias is more or less pronounced, the truth about the role of religion in helping slaves cope with their hardships is evident: religion gave slaves a sense of personhood, dignity and power that they were otherwise denied in their lives, a way of showing the world their humanity and a way of resisting the gruesome experience of slavery.

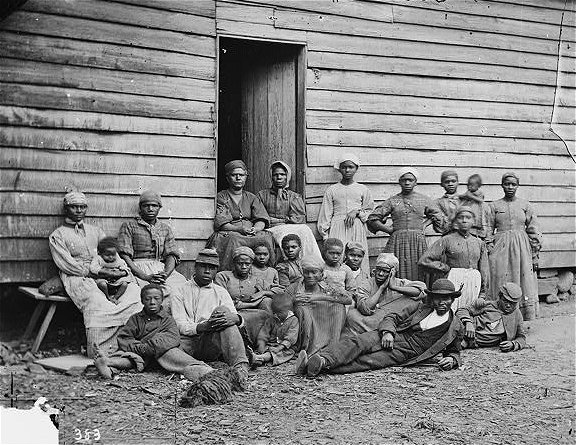

From the 1920s to the 1960s, Newbell N. Puckett was the major name in researching religion and slavery. He affirmed that most African-American religious beliefs were borrowed from European Americans.i Slave women were especially prone to this influence, since they were working in the houses of their masters, and passed on this knowledge to their children,ii which perpetuated the European beliefs in the slave population at large. Such beliefs as the superstitions related to death (e.g., “do not count carriages in a funeral procession”),iii most positive control signs (e.g., finding lost things by various meansiv, divining your future matev), or prophetic signs and omens (e.g., black cats are bad signsvi) are European in origin, according to Puckett. In addition, in his view, blacks emulated white culture in general, adopting Christianity but keeping the African tendency of concentrating on the relationship between man and God, with no heavy accent on morality. Thus, he contended, cursing, drinking, adultery, theft, and lying were not considered big sins by most slaves.vii However, Puckett contended that Voodoo and conjuration might be of African origin, but even in this case some beliefs were probably coming from European sources.viii Although Puckett exhibits a very Euro-centric and racist bias in his pages, there are, in his writing, hints of how slaves used religion to resist slavery. Some examples include hoodoo doctors giving charms to run away,ix root chewingx or walking backwards and throwing dirt over the left shoulder to avoid whipping,xi and bewitching the master’s wife to feel the whipping.xii He also contended that black churches had their own traits: the music, songs, and the spontaneous dance-rhythm.xiii Moreover, learning the bible by singing (because slaves were not taught to read or write), and singing spirituals to let fellow slaves know of a religious meeting at nightxiv were also noted by Puckett as traits of the slaves’ agency.In the 1970s, the focus changed, as Albert Raboteau’s analysis of slave religion demonstrates. The ways in which slaves adapted Christianity to their own needs is emphasized, and the slaves’ agency becomes more pronounced. Thus, slaves accepted Christianity not because their masters imposed it on them, but because it was a trend in Africa, from where they had come, and some refused to adopt it because in Africa they had adopted Islam.xv Also, Christianity was adapted and in some cases converged with African beliefs.xvi One example would be the religious dancing and shouting, which originated in the African spirit possessions but now represented Christian ecstatic experiences.xvii In addition, religion compensated for the hard life of slavery and helped in the resistance of slaves to it.xviii The latter example stands for resistance as well, since it empowered slaves to ask for the back-rails on seats to be removed so that they could pray.xix Their prayers were also symbols of resistance (e.g., they prayed for freedom, they prayed even when they were forbidden to, and they refused to pray for the Confederacy, when their masters ordered them to),xx and spirituals were shouted, dramatized, giving slaves strength, meaning and hope.xxi Despite the white ministers’ trying to label these traditions as sins, African-Americans kept them alive.xxii Moreover, slaves accused their masters through other whites, formed Christian fellowships, organized their own churches (African Baptist Churches),xxiii and had their own black preachers, who obtained the license to preach and were very eloquent, thus proving the abilities of blacks.xxiv These considerations of Raboteau are not Euro-centric anymore and focus on the slaves’ agency-something that was denied to them in most of Puckett’s pages. This trend of focusing on the slaves’ agency continued in the next decade. In a collection of essays, Masters and Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, the focus is on the slave communities’ adaptation of Christianity. Illustrative to this were the biracial churches, in which slaves could not only show their humanity but also carve out their own space, in response to the segregation policies. Thus, slaves and masters were recorded separated or together, according to the whims of the church clerk, sometimes they were baptized together ,xxv the death of slaves was faithfully recorded, and baptisms and licensing of black preachers gave them a positive sense of self.xxvi Nonetheless, because some churches did not allow slaves to attend unless they had their master’s permission, slaves had to stay in separate pews or galleries, and were not always extended the right hand of fellowship or even called “Brother” or “Sister,” slaves built their own community and Christian fellowships, by worshipping in their quarters, at night, and praying for freedom.xxvii Moreover, independent Protestant Black churches arose from the dissatisfaction of slaves and free Blacks with the white community and preachers (e.g., preaching about servants having to be obedient, but masters still maltreated them). This also offered slaves an opportunity to exert leadership and develop their ministry skills, although many times black churches were under white supervision and representation (e.g., the Poindexter code required a white preacher or two whites to attend any Black church and by the 1830s no free or slave black could preach).xxviii Other forms of resistance to the control of slave-owners were related to religion, as well. Many slaves converted to another denomination than their masters urged them to (e.g., becoming Baptist instead of Methodist, singing Methodist hymns instead of practicing Catholicism)xxix or because of the inadequate conditions of worship, especially in the case of Catholicism (e.g., foreign-born priests, understaffed churches, priests breaking the silence of confession, and having to take communion after whites and free blacks).xxx Moreover, slaves took Catholicism and adapted it through syncretism with African religious traditions (e.g., using candles, feast days, burial customs etc. in their rituals and upheld the image of the healing, exorcist priest). xxxi However, even when they did stay in the faith, slaves found ways of resisting the slave-owner’s control: in the case of Catholicism, they complained to the superiors of Jesuit priests who maltreated them, and sought top have their marriages blessed to force their masters to preserve the union and recognize their humanity.xxxii If up until now, slaves are shown as being imitators of the European culture of their masters, and then shown as agents of their religious life and as resisting the terrible institution of slavery through religion, the 1990s see the start of a gendered approach to slave religion. Patricia Morton focused on slave women, their common images of Jezebels and Mammys, their lack of protection in front of hard labor, and their lack of being respected as women and mothers. Being one of the first Methodists, slave women found meaning and hope in religion in times of sickness and death,xxxiii but also in such concepts as the sacredness of motherhood and personhood,xxxiv and in the principles upheld by the Methodists (e.g., humility, piety, charity, sobriety, love, simplicity), all in contrast to the property, status and wealth values of slave-owners.xxxv This, in itself was a way of resistance. Other forms of resistance included demonstrative, emotional conversion experiences in which slave women would find the personhood and dignity refused them by their owners, fighting for their bodies-temples of the Holy Spirit-and thus not only denying the Jezebel image imposed on them but also complaining about the slave men’s sexual abuses (complaining about their masters sexually abusing them was not possible).xxxvi Another way of resisting slavery was through baptism: by participating in church services, slave women pricked their owners’ consciousness about their humanity, and showed their maternal love. Slave women whose children were being sold away had at least the hope that God would protect them and she would meet them again in Heaven.xxxvii Thus, religion was a comfort in this world for slave women, especially when they were separated from their children. Religion also provided them with the opportunity to gain some education, as Methodist preachers often encouraged owners to teach slaves to read .xxxviii One final and crucial role that religion played in the lives of slave women (and fueled their resistance to slavery) was to help them find a sense of sisterhood, through such things as being able to meet in church, communally helping the church, nursing the ill, and taking care of the children. Thus, because slaves had a flexible definition of family, just like the church considered everyone a big family, many differences between slave women (e.g., field vs. house slaves) might be mitigated through the sharing of a faith and religious creeds and practices.xxxix Finally, by 2004, when Dorothea S. Ruiz’s book, Amazing Grace: African American Grandmothers as caregivers and Conveyors of Traditional Values, appears, the approach to slave religion is not only free of bias but also gendered. Ruiz is even more specific in her gendered approach, focusing on older slave women. Grandmothers were instrumental as caregivers and nurturers in the extended family network. Being the ones to impart the traditions and values to the young generation, through storytelling, they were the ones who set the standard for suitable behavior-all this, while withstanding the brutality of slavery and empowering their families and fellow slaves. For this reason, they had a very high standing in the slave society and family.xl Through this role older slave women taught slave children the scriptures, Negro spirituals, prayers, and hymns, but they also taught them about the power of God, and social and spiritual values: self-respect, how to live a good life, the importance of giving back to the community, of serving God, of the need of women to take care of themselves.xli This ensured not only a good psychological standing for the slave community but fought against the objectification of slave women as Jezebels and Mammy’s and, in general, proved the humanity of the slaves. Religion was a stabilizing factor in the otherwise insecure and cruel slavery life, and grandmothers were the teachers and spiritual leaders, who practiced vividly the religion (e.g., older slave women led religious testimony and spirit possession and were more open than men in practicing religion) and taught the children the values and rituals of it.xlii Older slave women were the maintainers and fighters for hope, who emphasized the freedom of the spirit, giving encouragement and support to those around them, through their prayers for freedom, good crops, and good mental health, which they performed, encouraged the rest of the slave community to practice and taught the children.xliii Because of this, they ensured a good psychological health for the slaves and empowered the community, through strengthening communal relationships. Thus, as we follow this time trajectory one can see that from the 1920s to the 1960s, the views about slaves’ religion were very biased and Eurocentric, but even then, the forms of resistance to slave-owners’ control through religion were quite obvious. However, as one goes into the 1970s and 1980s, the focus fell more on the way slaves used religion to cope with slavery by adapting Christianity to their own needs, and thus on slaves’ agency. It is also clear from these analyses that this form of resistance helped slaves form more closely knit communities and determined the formation of independent Protestant Black Churches that would expand after the Civil War. Finally, in the 1990s and 2000s, in addition to a complete departure form the Euro-centric approach, a gendered approach was applied to the analysis of slaves’ religion, so that slave women, and later older slave women, received the credit for upholding and perpetuating religious practices and beliefs. This they did through their challenges to such images as the Jezebel and Mammy, through teaching their children religious and moral values, and through maintaining a good psychological standing and an empowerment through prayer of the community, thus demonstrating the humanity and dignity of slaves. ReferencesBoles, John B., ed. Masters and Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 1740-1870. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1988. Morton, Patricia. Discovering the Women in Slavery: Emancipating Perspectives on the American Past. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996. Puckett, Newbell N. The Magic and Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926. Reprinted by Dover, New York, 1969. Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion: The Invisible Institution in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Ruiz, Dorothy S. Amazing Grace: African American Grandmothers as caregivers and Conveyors of Traditional Values. Westport: Praeger, 2004. Endnotes[i] Newbell N. Puckett, The Magic and Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926. Reprinted by Dover, New York, 1969): 1-2. ii.) Ibid., 577. iii.) Ibid., 81-9. iv.) Ibid., 324. v.) Ibid., 326-7. vi.) Ibid., 467-8. vii.) Ibid., 520-7. viii.) Ibid., 221. ix.) Ibid., 209. x.) Ibid., 276. xi.) Ibid., 318. xii.) Ibid., 284. xiii.) Ibid., 58-64. xiv.) Ibid., 71-3. xv.) Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The Invisible Institution in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978): 44-7. xvi.) Ibid., 58-9. xvii.) Ibid., 63-8. xviii.) Ibid., 36. xix.) Ibid., 68. xx.) Ibid., 307-8. xxi.) Ibid., 243-66. xxii.) Ibid., 72. xxiii.) Ibid., 180-210. xxiv.) Ibid., 231-8. xxv.) John B. Boles, ed., Masters and Slaves in the House of the Lord: Race and Religion in the American South, 1740-1870 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1988): 38-42. xxvi.) Ibid., 78-9. xxvii.) Ibid., 66-71. xxviii.) Ibid., 46-56, 65. xxix.) Ibid., 86, 136. xxx.) Ibid., 132-5. xxxi.) Ibid., 192. xxxii.) Ibid., 128-9, 138-9. xxxiii.) Patricia Morton, Discovering the Women in Slavery: Emancipating Perspectives on the American Past (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996): 208. xxxiv.) Ibid., 204. xxxv.) Ibid., 205. xxxvi.) Ibid., 209-11. xxxvii.) Ibid., 216. xxxviii.) Ibid., 218-9. xxxix.) Ibid., 213-4. xl.) Dorothy S. Ruiz, Amazing Grace: African American Grandmothers as caregivers and Conveyors of Traditional Values (Westport: Praeger, 2004): 1-3. xli.) Ibid., 4-7. xlii.) Ibid., 8-9. xliii.) Ibid., 11-13. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in African-American Studies |