The Cycle of Punishment in Producing Society

By

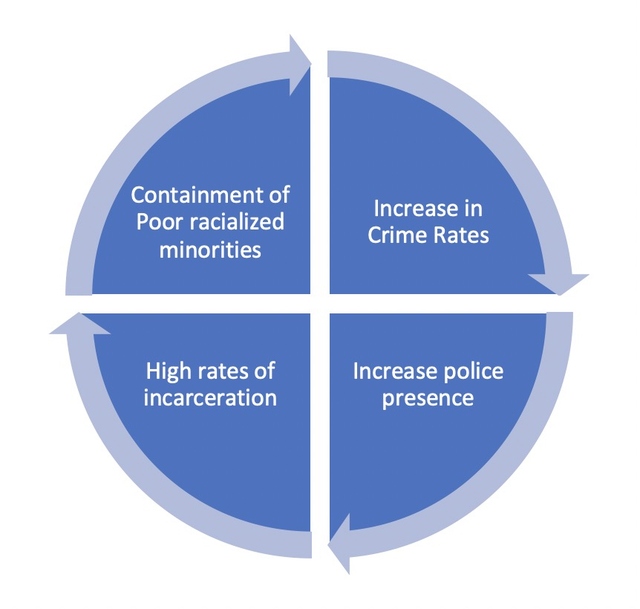

2020, Vol. 12 No. 10 | pg. 1/1 AbstractPunishment from the legal system is typically seen as a proper response to lawbreakers and criminal activity. However, we do not consider how punishment enables law enforcement and the legal system to further oppress marginalized and minority populations, and how it subjects a person to further control and intervention from the legal system. These “at-risk populations” tend to be marginalized and/or minority groups. The implication of this “at-risk” judgement, is that the legal system marries moral panic with racialized criminality. Stereotypes and the overrepresentation of Blacks, Hispanics and Indigenous people in our correctional facilities fuel our perception of race(s) that are ‘likely’ to be criminal. The cycling of offenders in and out of the judicial system is how the legal system controls them, for example: the use of criminal history as a tool to justify further monitoring, restrictions or the use of imprisonment. In addition, the state utilizes ‘banishment,’ as a means of controlling who can enter certain places. This means that the state can control where and when you enter certain places, who you can communicate with, their access to goods and services, and even the current and former ‘spaces’ that a person occupies. This paper argues that punishment creates social order by looking at the ways in which the state utilizes punishment as a form of control over the offender’s or minority population’s lives. The State does this by using civil infractions to warrant the surveillance of the offender’s life and using past and future infractions as more justified reasons of continuous intrusion. Meanwhile, the judicial process is a confusing and degrading experience for offenders entering the criminal justice system. Furthermore, the State uses space as a means of ‘moving punishment,’ in the way that it moves undesirable people out of specific areas through banishment, exclusion orders, or concentrated disadvantage. Lastly, the State produces social control through the creation of moral panic utilizing the ideology of the racialized ‘criminal man,’ to warrant containment, punitive sentences, and the removal of people of colour away from areas that are frequented by high-class members of society. Punishment creates social order by utilizing control over society’s members. In the United States, most criminal cases are misdemeanors (minor offences), and thus, making punishment a light sentence: usually in a form of a fine, or community service. Despite the punishment itself being light (in terms of severity) and a form of deterrence, the state employs it as a form of control over these individuals. For example, misdemeanors can be converted into a felony if the prosecutor has enough aggravating factor[s] to use against you – such as a history committing [similar] misdemeanor offences. According to Kohler-Hausmann (2013), a felony is a “mark,” or label that allows the state to control you. This mark communicates to members or institutions within a society that you are an offender and thus, opportunities become limited, and access to full participation in society becomes curtailed. More specifically, the members that tend to be excluded from participation in society are the marginalized populations: immigrants, people of colour, and minority groups and it is these marginalized groups that receive continuous harassment, and surveillance from police. For example, in the Rios (2011) reading, Spider had a near death experience because one of his friend’s was wearing red which mistakenly implied that he was part of a rival gang. Due to this incident, police labeled Spider as a gang member, and thus justified the police’s continuous surveillance on Spider, which potentially may lead police pressing serious charges on Spider in a future run-in, because of this gang-member label the police assumed of him. This marking leads to a funnelling of poor, people of colour within the criminal justice system, and keeps them in this cycle. This cycle demonstrates how the state can control social order using misdemeanor convictions as a mechanism to justify further surveillance, and intervention of one’s life. The criminal justice system uses misdemeanor charges or labels, to demonstrate your proneness to criminality in order to control aspects of your life to reduce your likelihood of committing a crime. For example: controlling areas where you can and cannot frequent, people you are ordered to abstain from socializing with, and whether you must attend a program for drugs, anger, or alcohol. After entering the criminal justice system, the tate further controls the offenders by subjecting them to the humiliation of procedural hassle and performance evaluation. Procedural hassle is the confusing, embarrassing, and humiliating process one endures when going through a trial. Kohler-Hausmann (2013) explains that the procedural hassle is “secondary prisonization” of the offenders because they do not have the freedom to decide administrative aspects of their trial such as: how long it will be or how long the case will run in general, and thus, this leaves them in a constant state of confusion – and victimization by the penal state. Procedural hassle contributes to the state’s control of social order, because this forces the offenders and compels them to obey the courts requirements and orders. This forces offenders to sacrifice work, social, and family obligations to attend to the demands of the court. As stated above, Kohler-Hausmann (2013) states that majority of criminal misdemeanor arrests were committed by Black people, with Hispanic being second, and White being the lowest. This is significant, because Black and Hispanic groups are frequently targeted for arrests and surveillance – and coupled with the fact that they are groups that are subjected to state oppressive tactics, it does not give them enough resources to cover the sacrificed obligations of work and family – such as finding a babysitter, or demonstrating competency in his/her job to land a promotion. Performance is employed to show one’s governability – meaning that you can prove your compliance and submission to the state. An example of performance would be having to do community service as part of your ‘punishment,’ or condition to be allowed back into society. If one refuses or fails to do this assigned duty, task or activity they are subjected to further sanctions and thus the state – thus, further marking you as someone who is not ready to merge back into society, and requires more surveillance, or intervention from the state (such as prison time or probation). Rios (2011) explains that the state involves other local actors to further expand its control over offenders or ‘high-risk for criminality’ people (impoverished, people of colour). The state uses probation to govern and monitor youths’ lives to deter (further) criminal behaviour, however, in reality the youth in Rios’s (2011) article state that meeting with a probation officer is degrading, humiliating, embarrassing, and that it was not a positive experience, nor helpful in their attempt to change out of a criminal lifestyle. Probation officers they explained, expected failure from them, and that having public meetings in community centres only further isolated them from society, and marked them as the “troubled kids” to avoid. The usage of probation allows the state to control, where, when, and who these youths can frequent – because failure to obey these orders results in further punishment – which ironically, was the goal to avoid when these youths were given probation in the beginning. Punishment produces social order by controlling who is allowed in particular ‘spaces.’ When we refer to space, we are not only referring to the areas we can see, but also how the space produces social relations between people within an area. Punishment produces social order by using space as an area they can control by determining who gets placed there. For example, one of your requirements on your probation may be to avoid certain areas, parks, streets, neighbourhoods, or actual places – or the state can remove you from the general sphere and place you in a different space: prison. Prison is a space where your rights and freedoms are limited or removed such as having the ability to vote and having the freedom of choosing when to wake up, eat, and sleep. Every action you do is monitored and scrutinized to ensure your governability. Cities may invoke something called a ‘Park Exclusion Order,’ and this is when the city can forbid you to enter a park for non-criminal matters, but rather an infraction of city bylaws, for example: being present during after hours, littering, or having an open container of alcohol (Beckett, and Herbert, 2010). Although, you are not going to jail for committing these infractions, the city punishes you by banning you to enter for a period of time. As a result of this being a civil infraction and not a criminal one, the city can bypass due process and the ban is immediately effective. Although the person is not going to jail for these minor infractions, it does not mean that this is a substitute of punishment – it is the continuation of it. Further infractions allow for continuous and (harsher) punishment upon the individual. Other than controlling where people have access too, the state can alter the space to move undesirable people elsewhere. For example, the gentrification of Parkdale in Toronto. Parkdale was an area where there were it had a high concentration of immigrants as well as high crime rates, however, over the years, Parkdale has been remoulded into a neighbourhood that looks inviting, coupled with the fact that it has been unofficially renamed “Veganville or Vegandale,” with independent vegan restaurants sprouting up fast on every corner. As new urban developments came to be, it pushed impoverished people out of the city because they no longer had the resources to remain in the city. It became too expensive to live in the area and stores were demolished to make room for condominiums. Another example, is in Lynch, Omori, Roussell and Valasik’s (2013), article where they discuss how San Francisco redesigned itself to become the ‘West Coast Manhattan’, and the development of high-rise condos, skyscrapers, upscale buildings and houses inevitably forced out the poor residents to live elsewhere. The removal of poor individuals from these cities Beckett and Herbert (2010), refer to it as ‘banishment.’ Banishment is punishment in the sense that it does deprive one of their liberty: through restriction of mobility, no access to former frequented spaces, and the segregation from loved ones; autonomy: because the state is intervening into your life, and you no longer have control of it; goods/services: because you no longer have access to financial, educational opportunities or assistance; security: because you become isolated from your family/support networks; and lastly, psychic pain: where one feels mental distress over the loss of family/societal ties, and/or the consequence of ‘marking’ (Beckett, and Herbert, 2010). Banishment is exactly how punishment creates social order in society. Once these impoverished people are removed, they congregate elsewhere, thus also moving the social problems – not solving them. This high concentration of impoverished people in a specific area, raises the suspicion of the police which leads police to patrol, and monitor the areas more frequently, thus leading to more criminal charges which leads to more surveillance. This is called the ‘Cycle of Disadvantage’ (Sampson and Loeffler, 2010). Punishment produces social order through the marriage between moral panic and racialized criminality. Referring to Clarke, Critcher, Hall, Jefferson and Roberts’s (2013) article, punishment can be used to create social order by implementing harsher punishments or imprisoning more individuals coming from a particular background. When someone thinks of criminals, they assume someone of either Hispanic or Black descent, dressing like a gangster, committing street-level violent offences. Moral panic is caused when people can no longer relate to each other, or the dominant culture feels that these different people are threatening the unified identity, or hegemony (Clarke et al. 2013). This difference tends to be on racial grounds, and they use these racial differences to justify state intrusion and control over the minority’s lives. When referring to violent crimes, people firstly think of an armed and dangerous Black man than a White man, and it is precisely this stereotypical assumption of the ‘criminal man,’ that perpetuates the ongoing funnelling of Black men into our criminal justice system. With the funnelling of many Black men into the criminal justice system, it conveys the message that these kinds of people are dangerous and to be avoided, and that they are the causes of our social problems – or of violent crimes in our neighbourhoods. A big influencer on how we view ourselves and other members in society is media. Media has the ability to convey sensationalized messages to a wide network of people and it is also where these cultural meanings and symbols are being created, developed, and circulated. When hegemony is under threat in society, punitive action becomes the choice of action because the (unified) dominant culture can no longer cultivate consensus among its people (Clarke et al. 2013). These differences among people in society (race) causes society’s harmony to disintegrate and become fragmented. This instability causes punitive attitudes among the dominant class and warrants punitive responses against people of colour who are seen as the threat (Clarke et al. 2013). The state using racialized criminality as a justification to control these minority, impoverished populations is how punishment produces social order. If the impoverished, minority population is kept checked, imprisoned, and contained – social order within a given society is harmonious because nothing is threatening the dominant culture/hegemony. The state employs punishment to create social order by exploiting non-criminal infractions as reasons to have criminal sanctions used upon you, using public space to control the movement of the impoverished, minority people, and using racialized criminality to instill moral panic and sensationalized messages to members of society to justify the penal practices used against these minority groups. These methods do not replace punishment in the classical way we know about it – which is imprisonment, but rather, these mechanisms are new ways of punishment to continuously surveillance the minority group and keep them from threatening the dominant authority and/or culture. When the state utilizes punishment to create social order, it is not only to maintain harmony and peace, but rather to also to maintain the status quo of society and not give opportunity for the minority class to threaten the hegemony of the dominant group. ReferencesBeckett, Katherine and Steve Herbert. 2010. “Penal Boundaries: Banishment and the Expansion of Punishment.”Law & Social Inquiry35(01):1–38. Hall, Stuart, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, and Brian Roberts. 2013. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Kohler-Hausmann, Issa. 2013. "Misdemeanor Justice: Control without Conviction."American Journal of Sociology119(2):351-393 Lynch, Mona, Marisa Omori, Aaron Roussell, and Matthew Valasik. n.d. “Policing The ‘Progressive’ City: The Racialized Geography of Drug Law Enforcement.” Theoretical Criminology 17(3):335–57. Rios, Victor M. 2011. Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys. New York, NY: New York University Press. Sampson, Robert J., and Charles Loeffler. 2010. "Punishment's Place: The Local Concentration of Mass Incarceration." Daedalus 139(3):20-31,145-146 Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Sociology |