Appropriation in Contemporary Art

By

2011, Vol. 3 No. 06 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

Appropriation refers to the act of borrowing or reusing existing elements within a new work. Post-modern appropriation artists, including Barbara Kruger, are keen to deny the notion of ‘originality’.2 They believe that in borrowing existing imagery or elements of imagery, they are re-contextualising or appropriating the original imagery, allowing the viewer to renegotiate the meaning of the original in a different, more relevant, or more current context. "I'm interested in coupling the ingratiation of wishful thinking with the criticality of knowing better. To use the device to get people to look at the picture, and then to displace the conventional meaning that an image usually carries with perhaps a number of different readings."

Barbara Kruger, 1987.1 In separating images from the original context of their own media, we allow them to take on new and varied meanings. The process and nature of appropriation has considered by anthropologists as part of the study of cultural change and cross-cultural contact.3 Images and elements of culture that have been appropriated commonly involve famous and recognisable works of art, well known literature, and easily accessible images from the media.The first artist to successfully demonstrate forms of appropriation within his or her work is widely considered to be Marcel Duchamp. He devised the concept of the ‘readymade’, which essentially involved an item being chosen by the artist, signed by the artist and repositioned into a gallery context. By asking the viewer to consider the object as art, Duchamp was appropriating it. For Duchamp, the work of the artist was in selecting the object. Whilst the beginnings of appropriation can be located to the beginning of the 20th century through the innovations of Duchamp, it is often said that if the art of the 1980’s could be epitomised by any one technique or practice, it would be appropriation.4 This essay focuses on contemporary examples of this type of work.

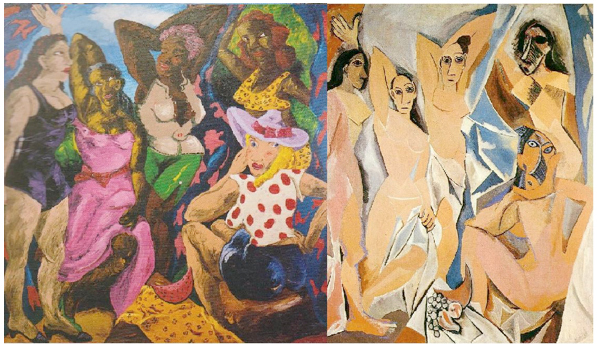

Left: Robert Colesscott, Les Demoiselles d’Alabama, 19855; Right: Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 19076 Above we see a contemporary example of appropriation, a painting which borrows its narrative and composition from the infamous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Picasso. Here Colesscott has developed Picasso’s abstraction and ‘Africanism’ in line with European influences. Colescott has made this famous image his own, in terms of colour and content, whilst still making his inspiration clear. The historical reference to Picasso is there, but this is undeniably the artist’s own work. Other types of appropriation often do not have such clear differences between the original and the newly appropriated piece. The concepts of originality and of authorship are central to the debate of appropriation in contemporary art. We shall discuss these in depth in order to contextualise the works we will investigate later in this essay. To properly examine the concept it is also necessary to consider the work of the artists associated with appropriation with regards to their motivations, reasoning, and the effect of their work. The term ‘author’ refers to one who originates or gives existence to a piece of work. Authorship then, determines a responsibility for what is created by that author. The practice of appropriation is often thought to support the point of view that authorship in art is an outmoded or misguided concept.7 Perhaps the most famous supporter of this notion was Roland Barthes. His 1966 work ‘The Death of the Author’ argued that we should not look to the creator of a literary or artistic work when attempting to interpret the meaning inherent within. “The explanation of a work is always sought in the man or woman who created it… (but) it is language which speaks; not the author.”8 With appropriated works, the viewer is less likely to consider the role of the author or artist in constructing interpretations and opinions of the work if they are aware of the work from which it was appropriated. Questions are more likely to concern the validity of the work in a more current context, and the issues raised by the resurrection and re-contextualising of the original. Barthes finishes his essay by affirming, “The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.”9 , Suggesting that one can and should only interpret a work on it’s own terms and merit, not that of the person who created it. In contrast to the view supported by the much-cited words of Roland Barthes, is the view that appropriation can in fact strengthen and reaffirm the concept of authorship within art. In her 2005 essay Appropriation and Authorship in Contemporary Art, Sherri Irvin argues:

Authorship then, is a concept we most consider when discussing appropriated works. The evidence presented suggests that the notion of authorship is still very much present within appropriation in contemporary art. However, the weight of Barthes argument is such that we must take it into account. Perhaps a diminished responsibility or authorship is something we can consider in this context. Perhaps the most central theme in the discourse on appropriation is the issue of originality. The primary question we must address is – what is originality? It is a quality that can refer to the circumstances of creation – i.e. something that is un-plagiarised and the invention of the artist or author? We can approach originality in two ways: as a property of the work of art itself, or alternatively as a property of the artist.11 As we have said, many appropriation artists are keen to deny the notion of originality. In a paper addressing the notion of originality within appropriated art, Julie Van Camp states:

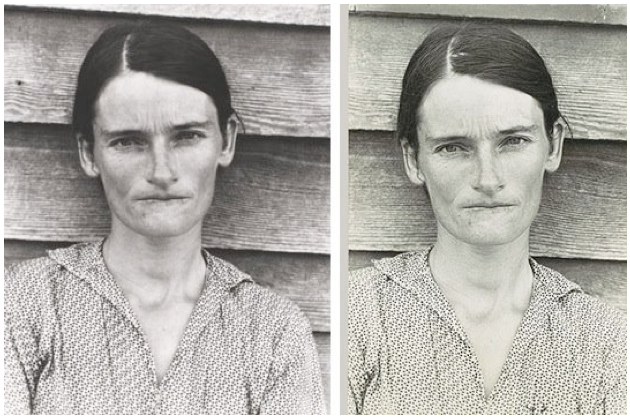

This statement is problematic, as it is almost dismissive of the ability of an artist who chooses appropriation as their form of representation. Let us look to the example of Sherrie Levine, perhaps the most well-known and cited appropriation artist. Levine worked first with collage, but is most known for her work with re-photography – taking photographs of well known photographic images from books and catalogues, which she then presents as her own work. In 1979 she photographed work by photographer Walker Evans from 1936. Her work did not attempt to edit or manipulate any of these images, but simply capture them.

Left: Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans, 1981; Right: Walker Evans, Alabama Tenant Farmer's Wife, 193613 By bringing this work back into the conscious of the art world, she was advancing the art form that is photography by using it to increase our awareness of already existing imagery. On a basic level, we tend to equate originality with aesthetic newness. Why should a new concept – the concept of appropriation and the utilising of existing imagery – be deemed unoriginal? Sherrie Levine was interested in the idea of “multiple images and mechanical reproduction”. She said of her work “it was never an issue of morality; it was always an issue of utility.”14 This statement is easily applied to the works of other appropriation artists, as well as Levine’s. Barbara Kruger’s work utilised media imagery in an attempt to interpret consumer society. Her background was in media and advertising, having worked as a graphic designer, and picture editor for Condé Nast. Her work “combines compelling images… with pungently confrontational assertations to expose stereotypes beneath.”15 Her most famous work typically combines black and white photography, overlaid with text in a red and white typeface. Statements within her work such as “We don’t need another hero”, “Who knows that depression lurks when power is near?” and “Fund healthcare not warfare” have naturally led viewers to consider her art as politically themed. Kruger however, finds the political label often attached to her work problematic. In a 1988 interview she insists, “I work with pictures and words because they have the ability to determine who we are, what we want to be and who we become.”16 Whilst there may or may not be political elements to Kruger’s work, the undeniable underlying theme prominent throughout all of her works is the issue of our consumer society. By using images available for public consumption in a composition with a thought provoking statement, Kruger is asking us to rethink the images that we consume on a daily basis in terms of perception and how underlying messages function within this imagery. Kruger’s use of “less abstract subjects than Duchamp’s”17 may well increase the accessibility of her work, making it familiar and thus available to a wider audience.

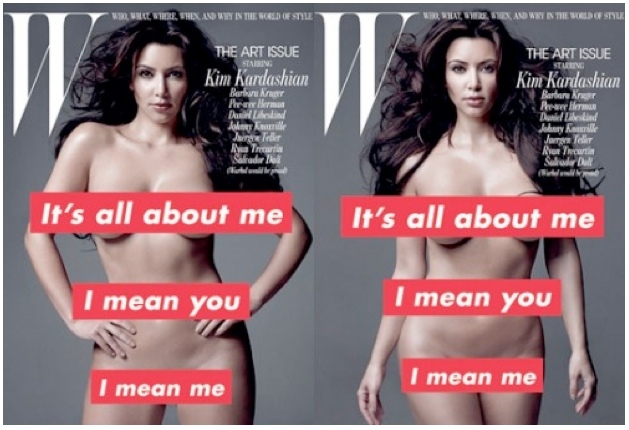

Barbara Kruger is still creating art today, and the most current example of her work is seen in the November 2010 issue of W Magazine: The Art Issue featuring reality TV star Kim Kardashian on the cover. It features a naked Kardashian with Kruger’s famous red and white block text covering her modesty. The text reads ‘It’s all about me/I mean you/I mean me”. Combining the words of Kruger and the image of currently world famous Kardashian is a form of appropriation in itself. W Magazine is appropriating the star into an art context, by simply featuring her on the cover of their art issue. This could be an attempt to consider another area of our consumer culture, which the cover star makes her living from – reality TV – as an art form. Here W Magazine has appropriated the image of Kardashian, and is therefore asking us to consider the ‘art’ of reality TV.

W Magazine, The Art Issue, November 201019 The idea of using appropriation to address the consumption of imagery is something that was addressed in the pivotal 1977 exhibition Pictures. In the exhibition catalogue, curator Douglas Crimp noted to growing extent to which our day-to-day experience is governed by images from the media. He said: “Next to these pictures our firsthand experience begins to retreat, to seem more and more trivial…It therefore becomes imperative to understand the picture itself.”20 Crimp’s exhibition at the New York Artist’s Space used the work of artists including Sherrie Levine, Troy Bauntuch and Robert Longo to display appropriation as a new mode of representation. The exhibition has a considerable impact on the art world – it launched a new art based on the (usually unauthorised) possession of the images and artefacts of others.21 Richard Prince is an appropriation artist who is commonly thought to have featured in the pivotal Pictures exhibition, despite having no connections with it whatsoever. His work however, addresses the same issues tackled by the artists in Crimp’s exhibition. Much of his work focused on the re-photography of caption less advertisements for high end products such as perfume, fashion and watches. Interested in commodity and consumption, “Prince was treated as a social communicator whose aim was to critique commodification.”22

Here Prince has re-photographed and re-proportioned an image from an advertisement for Marlboro cigarettes. Much like the work of Sherrie Levine, there is very little that the artist Richard Prince has done to alter the original work. The questions of originality and authorship continually surround Prince and his work. When asked to comment about his ‘borrowings’ for an article in the New York Times, he declined to comment, stating only: “I never associated advertisements with having an author.”24 The discourse and attention surrounding the concept of appropriation is so extensive that we must consider it an art form. One of Richard Prince’s Marlboro appropriation photographs sold at Christies for $1.2 million in 2005, setting a new record for appropriation art.25 Art of all genres has something that makes us think, or evokes a feeling – any feeling, in it’s viewer. Whilst some may consider appropriation as copying or forgery, it is clear that the controversial art form has now gained recognition worthy of a contemporary art practice. ReferencesAfter Sherrie Levine by Jeanne Siegel. (2001.) Available at: www.artnotart.com/sherrielevine/arts.Su.85.html (Accessed 4th Feburary 2011). ‘Artisan of History’. (2009). Available at: http://artisanhistory.blogspot.com/2009_09_01_archive.html Accessed 20th February 2011. Barthes, R. (1967). ‘The Death of the Author’ in Stygall, G (2002). Academic Discourse: Readings for Argument and Analysis, Taylor and Francis: London. Dunleavy, D. (2007). ‘The irony of art in a culture of appropriation’. Available at: http://ddunleavy.typepad.com/the_big_picture/2007/12/the-irony-of-ar.html Accessed 20th February 2011 Evans, D. (2009). Appropriation. Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press: London/Massachusetts. Irvin, S. (2005). ‘Appropriation and Authorship in Contemporary Art’. British Journal of Aesthetics, Vol 45, No. 2. Kruger, B. (1999). Thinking of You. MIT Press: Massachusetts. ‘Mary Boone Gallery’ (2011) Available at: http://www.maryboonegallery.com/artist_info/pages/kruger/detail2.html Accessed 20th February 2011 Sandler, I. (1996). Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960’s to the Early 1990’s. Westview Press: Colorado. Siegel, J. (1988). Art Talk: the Early 80’s. Di Capo Press: Michigan Kennedy, R. (2007). ‘If the Copy Is an Artwork, Then What’s the Original?’. The New York Times [Online] Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/06/arts/design/06prin.html?_r=1&ex=1197867600&en=ce95b8dd14df4dd8&ei=5070&emc=eta1 Accessed 28th February 2011 W Magazine. (2010). Available at: http://www.wmagazine.com/celebrities/2010/11/kim_kardashian_queen_of_reality_tv_ss#slide=10 Accessed 22nd February 2011. Endnotes1.) Stiles, K (1996) Theories and documents of contemporary art: a sourcebook of artists' writings University of California Press: CA. p. 377 2.) Van Camp, J (2007) ‘Originality in Postmodern Appropriation Art’ The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 36: 4 p.247 3.) Schneider, A (2007) Appropriation as Practice. Art and Identity in Argentina, Palgrave Macmillan pp.24-5 4.) Sandler, I (1996) Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960’s to the Early 1990’s Westview Press: Colorado p. 321 5.) Image from ArtNet: Available at: http://www.artnet.com/Magazine/news/walrobinson/walrobinson9-1-2.asp Accessed 28th Febuary 2011 6.) Moma Collection Online: Available at: http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=79766 7.) Irvin, S (2005) ‘Appropriation and Authorship in Contemporary Art’ British Journal of Aesthetics, Vol 45, No. 2, p. 123 8.) Barthes, R (1967) ‘The Death of the Author’ in Stygall, G (2002) Academic Discourse: Readings for Argument and Analysis, Taylor and Francis: London p. 102 9.) Ibid p.106 10.) Irvin, S (2005) p.123 11.) Van Camp (2007) p.248 12.) Ibid. p.250 13.) http://artisanhistory.blogspot.com/2009_09_01_archive.html 14.) After Sherrie Levine by Jeanne Siegel (2001) Available at: www.artnotart.com/sherrielevine/arts.Su.85.html (Accessed 4th Feburary 2011) 15.) Siegel, J (1988) Art Talk: the Early 80’s Di Capo Press: Michigan p. 299 16.) Ibid, p. 303. 17.) Kruger, B (1999) Thinking of You MIT Press: Massachusetts p. 9. 18.) http://www.maryboonegallery.com/artist_info/pages/kruger/detail2.html 19.) http://www.wmagazine.com/celebrities/2010/11/kim_kardashian_queen_of_reality_tv_ss#slide=10 20.) Sandler, I (1996) p.319. 21.) Evans, D. (Eds.) (2009) Appropriation Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press: London/Massachusetts p. 12 22.) Sandler, I (1996) p. 326. 23.) http://ddunleavy.typepad.com/the_big_picture/2007/12/the-irony-of-ar.html 24.) Kennedy, R (2007) ‘If the Copy Is an Artwork, Then What’s the Original?’ The New York Times [Online] Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/06/arts/design/06prin.html?_r=1&ex=1197867600&en=ce95b8dd14df4dd8&ei=5070&emc=eta1 Accessed 28th Febuary 2010. 25.) Ibid. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Visual Arts |