The Sentimentality of Sterne's Tristram Shandy: A Mind and Body Story

By

2017, Vol. 9 No. 01 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

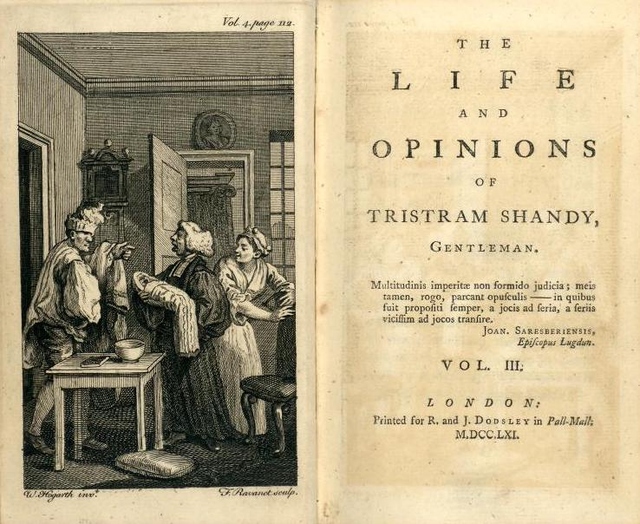

The literature of the 18th century includes parodies, satires, and denunciations; however, the role of sentimentality usually comes second when discussing the literary movements of the century. The author of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Laurence Sterne, is commonly known as he “who introduced the present mode of sentimental writing” (The Sentimental Magazine). Among authors such as Jonathan Swift, Henry Fielding, and Daniel Defoe his novel stands as a text outside the ordinary and invokes as much empathy as it does laughter. The text continually makes use of phallic symbols, follows a plot with no linearity, cuts out entire chapters, includes black pages, blank pages, and even a notorious marbled page. At the same time, his work produces immense feeling, so much so, that his name becomes synonymous with sentimentality itself. Sterne combines the two mediums of satire and sentimentality within his work to show the relationship between humor and emotion, between the body and mind, and between character and narrative. Furthermore, by means of the humor of the text it is possible to miss the intricacies of emotion that Sterne imbeds within his novel. Tristram Shandy presents mathematical proofs in order to show the location of the mind and body; it depicts characters not through words, but through simple actions such as a soft touching of the hand; it includes metanarratives, which invoke emotion in other characters as much as they do the narrator and reader; and, above all else it argues for moments of sentimentality, for moments when distraction and digression fade and all that remains is the resemblance of all mankind.The sentimentality of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy is present ab ovo and persists throughout the narrative as a complex relationship of mind and body. The text includes an early definition of their relationship by means of Tristram himself who states, “----I tremble to think what a foundation had been laid for a thousand weaknesses both of body and mind, which no skill of the physician or the philosopher could ever afterwards have set thoroughly to rights” (7). In effect, the body and mind are similar to the middle section of a venn diagram, where it is impossible to set them “to rights” or “into a proper condition or order” (OED). Furthermore, when there is change in one it effects the other and they share the entirety of their elements, similar to their weaknesses. This idea is present within an essay on characterization and body in Tristram Shandy, by Juliet McMaster who states, “mind and body—with the indissoluble links between them, and their simultaneous tragic and comic discontinuity—are surly the major overarching subject of Tristram Shandy” (199). Nonetheless, McMaster only explores their discontinuities and theorizes that Sterne “would have focused on the discontinuity of mind and body as the most fertile source of laughter” (200). This assumption of Sterne’s poetics indirectly calls into question the novel’s sentimentality. Accordingly, if the discontinuity of mind and body leads to the most fertile source of laughter, a consequence of their continuity is the most fertile source of sentiment. I argue the reason scenes, gestures, and actions in Tristram Shandy are potent and sentimental is due to the fact they occur when both body and mind are congruously working together without distraction: if humor is a consequence of their disconnection then sentimentality erupts from their synchronization. The main function of sentimentality is to display high emotion and “the tearful distresses of the virtuous, either at their own sorrows or at those of their friends” (Abrams, 360). It is critical to explore communication within the text, due to it being the method characters use to share these emotions and distresses. Ergo, an examination of Sterne’s method of communication is necessary to understand his sentimentality. In his work Sentiment and Sociability, John Mullan examines Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey and concludes that “perfectly intelligible conversation depends on gestures rather than words, on sensitivity to the non-verbal rather than confidence in what can be said […] sympathy is most graphic when it is not spoken” (158). In effect, gestures in A Sentimental Journey behave similarly to those of Tristram Shandy and are the primary source of communication, this means the most feasible communication of sentiment comes from the body. In the novel, Walter Shandy mentions communication through body when looking for a tutor with “a certain mien and motion of the body and all its parts, both in acting and speaking, which argues a man well within” (373). The “man well within” represents the mind, and to understand this mind we must focus on the person’s “mien and motion” or the gestures of their body. Moreover, the body becomes a vehicle for sentiment to travel from a character’s mind to their specific gestures and actions; and finally, to the narrator, other characters, and the readers themselves. Therefore, “’sociality’ is what we are to enter into when reading Sterne’s text” (Mullan, 159) and it is a sociality of gestures in which the body communicates sentiment. Furthermore, this correlates to a statement in the form of a mathematical proof that Walter states earlier in the narrative: “If death, said my father, reasoning with himself, is nothing but the separation of the soul from the body;--and it is true that people can walk about and do their business without brains,--then certes the soul does not inhabit there. Q.E.D” (131). The “brains” in this proof refers to the intellectual properties of the mind, as the proof separates it from both soul and body. Consequently, if the soul is not within the mind, it is a part of the body, since this passage mutually excludes them both, they are together and thus the body must be the vessel for the soul. In addition, the OED’s definition of “lack of soul” is “to lack spirit, sensitivity, or other qualities regarded as elevated or human; to lack sensibilityforsomething” and illustrates that since the body is a conduit for the “soul” it becomes the conduit for sensibility and sentiment as well. Therefore, sentiment must emerge from the body, and it is through the body characters of Tristram Shandy communicate their tearful distresses. The mind in Tristram Shandy is often spoken in relation to the body and rarely on its own. However, in a singular instance during volume three, the novel states its abstract understanding of the subject. In a discourse on time and infinity, Walter argues to comprehend these concepts it is essential to understand their origins. He then begins to paraphrase a passage on the mind from Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding:

This explanation on the processes of the mind figuratively portrays them as they literally are: a variety of neurons firing simultaneously, each contributing to a collection of ideas that embody a singular idea and in this case existence (Locke, 174). However, it also describes a separation between the body and mind by means of thinking about the concept of existence while the body performs simple actions similar to “smoking pipes” on its own. In summation, the passage demonstrates that minds examine a constant flux of ideas, and bodies continually perform basic actions without a thought. Therefore, in Tristram Shandy the resting condition of mind and body is a state of discontinuity that leads to the aforementioned humorous moments. Additionally, this resting discontinuity explains the reason humorous scenes outnumber the sentimental: the mind and body are fighting their equilibrium state during sentimental moments. Ergo, in order for sentiment to emerge, they must congruously work towards the same message and the mind must dismiss its distractions and focus on a singular subject while the body avails its own sensibility. According to M. H. Abrams, a fundamental aspect of sentimentalism includes the shedding of tears for the sorrows of others; in other words, the vicarious tears of sympathy for an individual’s pain become our own. Consequently, this sharing of heartache is integral to sentimentalism: it lifts the weight of sorrows and through mutual sympathy enables a mutual cheer for “’the general resemblance of the circumstances of all mankind to each other’” (Mullan, 31). The novel includes the ramifications this mutual sympathy can have on the mind and body, and the pleasure that arises from recognizing the general resemblance of mankind when it nears its conclusion. After the reenactment of Toby’s amours, Tristram states,

Here Tristram stands in for the reader and literally displays the intended effects of the sentimental moments he incorporates. Consequently, as the amours engulf his mind, his body vibrates and runs along with them, and through every oscillation of the body and emotional turn of the mind within his uncle Toby, he himself feels the same sentiment and rapture. Furthermore, when sentimentality is fully realized within Tristram Shandy, it is in harmony with the body and mind of the person speaking as well as the person listening. The moments of heartache within the novel are spoken with a utilization of both thought and gesture which creates the sympathy that Tristram embodies in this passage and in his own thoughts and gestures. Thus, during sentimental moments, there is no split focus, no humor, only the sharing of sentiment that resembles the mutual circumstances of mankind. The affects the novel intends and Sterne’s method of communication in relation to sentimentality are unorthodox; however, they elucidate the potency within minute details of Tristram Shandy. The miniscule gestures and the silences both short and long during scenes of emotional turmoil are as much the sunshine as the humor/digressions of the text and add to making it “one of life’s great consolations.” In the first sentimental moment the text enacts, it exemplifies the convergence of mind and body on a singular thought, the mutual sympathy for the circumstances of mankind, and the consequences of sentimentality through Yorick’s death:

The scarcity of dialogue and the silent conversation within this scene creates the rapture of emotion. Eugenius comes to say farewell to his friend and this goodbye is not spoken with words, rather it is with tears and two squeezes of the hand. The mirroring of their bodies through a squeeze of the hand as they meet and depart, the tears which start and end the scene, and the cutting of Eugenius’ heart by the broken shards of Yorick’s is the epitome of Sterne’s sentimentality: it is the singular idea of a “last farewell” spoken in the form of bodily gestures. The synchronization of mind and body embodies this brief memento mori to create sentimentality amidst the novel’s humor. Therefore, with the final bodily action of closing his eyes, Yorick’s mind also fades to blackness as the novel follows it with two black pages that mimic the effect of his closed eyelids. The sentimental departure of Eugenius from Yorrick parallels scenes in the latter section of the novel and a point in the narrative which pushes the limits of what a cooperation of mind and body can accomplish. This is The Story of Le Fevre, an interlude within Tristram Shandy that gives Sterne a great deal of recognition for his sensibility: “Mr. Sterne’s affecting Story of LE FEVRE has been so much admired by the sentimental part of the literary world” (Timbury, 5). There are two integral events within the Le Fevre frame narrative that invoke the elements of sentimentality and the first occurs when Toby hears the tale of his life:

The slow progression of Toby’s statements parallel his movements and the scene juxtaposes them to draw attention to the relationship between his thoughts and actions. In the first statement, there is the wishful thought of “he might march” alongside a hopeful smile; however, Trim’s rejection of Toby’s thought instigates a spark causing it and him to rise. In addition, Toby only has one shoe on, a reference to his own injury and his half commitment to the army at this moment. Nonetheless, as the thought of supporting Le Fevre engulfs his mind, his body moves with it and begins to march with the foot bearing a shoe, and this foot contrasts the other by the shoe being metonymic for his commitment to the army and his comrade. Furthermore, Trim through his negativity represents the impossibility of Le Fevre being able to march and Toby is fighting against him with the entirety of his mental focus and the actions of his body. Through this, Toby embodies another element within sentimental novels, the convention of “comprehending the pathos of narratives; the capacity to respond with tremulous sensibility to a tale of misfortune” (Mullan, 159). Toby, by means of his own mind and body imitates what he wants Le Fevre to accomplish and thus feels the emotional distresses of his narrative in every fiber of his own being. This leads to the second crucial event in The Story of Le Fevre and the peak of sentimentality within the novel. This frame narrative concludes with the death of the title character and as Tristram recounts it in detail, he feels the exasperations of both Le Fevre’s mind and body in his own; so much so, that he brings it to a close before Le Fevre ushers his last breath. In the final chapter of Le Fevre’s tale, Toby witnesses the tragic death of this young soldier:

The density of this moment results in a fruition of all the aforementioned sentimental qualities within the text and the utilization of both mind and body. In the passage’s first half, the “spirit” or sensibility which resides in the body slowly fades and Le Fevre is unable to move; however, the concrete focus of his heart, which is metonymic for the mind and “in the most general sense: the mind” (OED) itself rallies him back for a brief glance at Toby and his son. Le Fevre’s body responds to his mind and it appears as if his body is regaining its “spirit.” Moreover, this scene is now Le Fevre attempting with all his mental focus and bodily strength to march alongside his comrade Toby, and through this it creates a moment which radiates sentimentality. The second half omits Le Fevre, and leaves Tristram narrating the physical processes leading to death in a method which exhibits the resemblance of all mankind in the act of dying: there are no names in this death, just a lingering pulse which slowly fades. Nonetheless, Tristram never narrates its end, and the final word of “No” displays the sharing of pain through mutual anguish is why he cannot continue. Thus, the focus of every character, their minds and bodies, and the narrator himself is on Le Fevre’s death: there is no split focus during these sentimental moments. The sentimentality of Tristram Shandy arises from the synchronization of mind and body on a singular idea and though Tristram never explicitly describes what emotions characters intrinsically feel, they are present and “are wrapt up […] in a dark covering of uncrystalized flesh and blood” (66). The body becomes the medium for emotions to shine through when stakes are high and in these moments the mind focuses the entirety of its attention on what the body is trying to accomplish. The body may be uncrystalized and not instantly transparent, and emotions may not be instantly visible; nevertheless, when the mind’s focus shifts to a singular idea, “a man’s body and his mind, with the utmost reverence to both […] are exactly like a jerkin, and a jerkin’s lining:—rumple the one—you rumple the other” (144). When they are working together, their behavior is comparable to a jacket and its lining: they move together, function together, and focus on the same purpose. Thus, the outcome of their congruity is the sentimentality which Sterne’s text embodies: the absence of any split focus or humor and the sole idea of sharing emotions of mutual sympathy for the resemblance of all mankind. The farewell of Eugenius and the death of Le Fevre epitomize the sentimental moments which pervade the text and are two welcome pieces of sunshine that pierce through the humor of Sterne’s cock and bull story. ReferencesAbrams, Meyer H., and Geoffrey Galt Harpham. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 11th ed. California: Wadsworth, 2014. Print. Locke, John. An Essay concerning Human Understanding. Ed. R. S. Woolhouse. London: New York, 1997. Print. McMaster, Juliet. "Uncrystalized Flesh and Blood": The Body in Tristram Shandy." Eighteenth-Century Fiction 2.3 (1990): 197-214. Web. Mullan, John. Sentiment and Sociability: The Language of Feeling in the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon, 1988. Print. Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Ed. Melvyn New, and Joan New. London: Penguin, 2003. Print. The Sentimental Magazine: Or, General Assemblage of Science, Taste, And Entertainment. Calculated to Amuse the Mind, to Improve the Understanding, And to Amend the Heart. London: Printed for Authors, 1773. Print Timbury, Jane, and Laurence Sterne. The Story of Le Fevre from the Works of Mr. Sterne. Put into Verse by Jane Timbury. London: Printed for R. Jameson, 1787. Print. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |