Featured Article:The Colonial Subject: Seeing the Unseen and the Construction of Subjectivity in Apocalypse Now and La Noire de...

By

2016, Vol. 8 No. 09 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

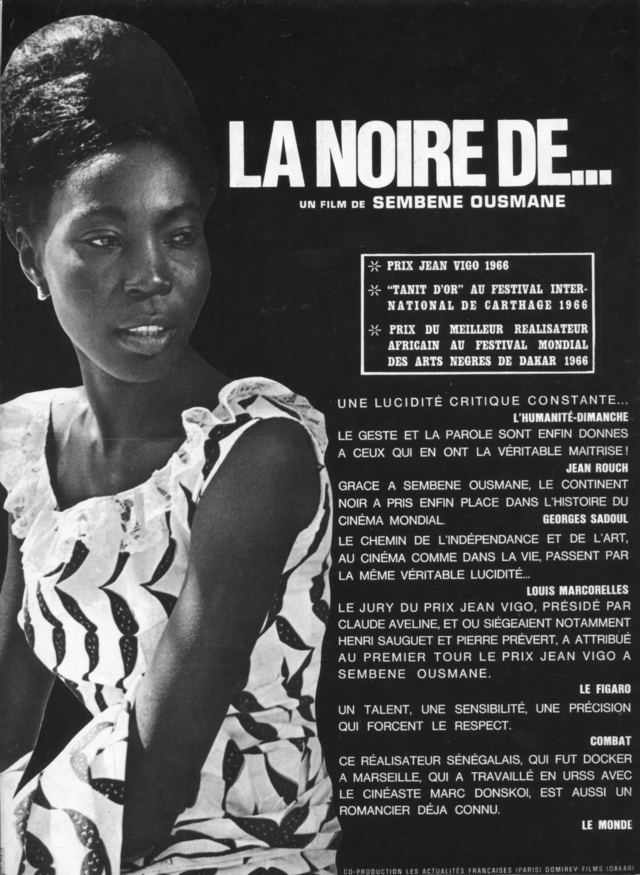

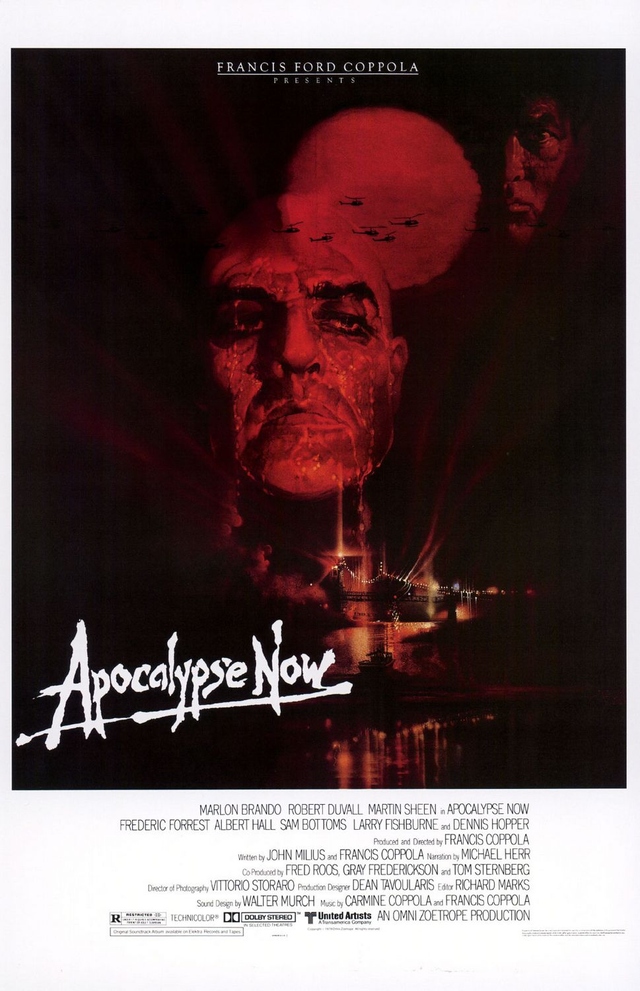

The evolution of the moving image from the seemingly simplistic Edison/Dickson shorts of the late 19th century to the technically complex CGI infused blockbusters flashing on multiplex screens today is certainly one propelled by opposition. Technological, theoretical, and formalistic innovations have both fostered and challenged audiences’ comprehension of cinematic texts leaving one to question the very ontological foundation of the cinematic medium itself. Light and darkness, time “embalmed” in a string of still frames and lived moments virtually repeating ad infinitum. The complex and multifaceted nature of cinema is further complicated by the unmistakable tension between the quasi-objective potential inherent in the medium—the camera merely operating as an observer—versus the unrestricted camera which functions as a metaphysical transport to the psychological and even physical experience of a distinct body. Upon close examination, it can be said that both of these modes of address are unique to cinema and arguing for the significance of one over the other is a fool’s errand. As such, this paper does not address this arguably problematic dichotomy but rather specifically examines and illustrates cinema’s exceptional power to make visible unique subjective states. Cinema has the exceptional ability to immerse us in unique subjective states It should be noted, however, that a simplistic reading of form alone is insufficient to deal with the question of the formation of subjectivity in the cinema as the subjectivization of a fictional character itself inherently points outward beyond the confines of the screen. In effect, to make visible internal processes of specific characters within a film, the characters themselves must of course be “defined” within their given universe. This process of fictional subjectivization, as seemingly removed from reality as it is, is discursively linked to existent structures of feeling at the time of creation/production and, indeed, at the time of reception. Furthermore, even a fairly straightforward discussion of exhibiting subjectivity within film must take into account that the formation of subjectivity is not simply an autonomous process but rather the construction of one’s self against and within. In effect, one exists in a permanent state of becoming constantly in discursive relations with existing and evolving ideological, economic, cultural, and sociopolitical forces.Becoming is not merely a process of choices and preferences but rather a reciprocal act of violence against an Other and within a larger network of social forces. To be, one has to actively exclude and is actively excluded. This seemingly extreme identitarianism is not wholly reliant on exclusion alone but also necessitates (by preference or force) the identification with a larger group (nation, race, gender, class, etc.). Subjectivity, therefore, is fundamentally a personal and shared state of becoming. This issue of identity and alterity need not be aggressive or explicitly enforced but to exist as an autonomous subject inherently means to exist in opposition to an Other, which in turn and seemingly contradictorily means to exist among others. Admittedly one must consider the multiplicity of frameworks involved in the formation of subjectivity beyond simply an Us/Them structure. However, taking into account disparate and conflicting discourses should not reduce the significance of specific identificatory fragments, particularly those forcefully and blatantly imposed through external sources, which will be discussed within the proceeding textual analyses. In light of this complex process, this paper proposes that subjective states made explicit within cinema should not be hermeneutically teased apart solely within the confines of the text itself but, instead, should be incorporated into larger structures of feeling. With this conception in mind, we can begin by analyzing precisely how subjectivity is constructed in two drastically different films and how each of these seemingly autonomous subjects presented within their respective narrative discourses function simultaneously as embodiments of a larger shared, cultural subjectivity and, thus, cannot be effectively understood without considering this broader context. Ousmane Sembène’s 1966 film La Noire de… and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 war epic Apocalypse Now will serve as two seemingly disparate examples of how decoding and interpreting a film’s construction, specifically dealing with character subjectivity, must additionally rely on questions of subjectivazation within and external to the text. In the 1916 book The Photoplay: A Psychological Study Hugo Munsterberg argues for a new understanding of the burgeoning medium of film. By removing the spatio-temporal shackles of lived time, the cinema invites a novel mode of artistic creation where the corporeal experience becomes secondary to the workings of the inner mind. The seemingly unprecedented yet, in Munsterberg’s opinion, largely untapped ability for the moving image to make purely mental and psychological processes manifest prompted Munsterberg’s manifesto of sorts in which he vociferously called for a cinema that does not limit itself to simply imitating nature or theater but rather explores and expresses “feeling and sentiment through means of its own” (15). To be sure, cinema had indeed exhibited signs of this potentiality prior to Munsterberg’s text. From the simple (yet quite ahead of its time) point-of-view shots in G.A. Smith’s 1900 film Grandma’s Reading Glass, to the whirling background superimposed behind a drunken man in Edwin S. Porter’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906), traces of cinema’s power to open a door into another’s subjectivity have essentially been with the medium since its inception. One of the most striking examples of this process of impressing “attention, memory, imagination, and emotion…on the bodily world” occurs in the introduction to Apocalypse Now. Before his excursion to assassinate rogue US military colonial Walter Kurtz (Marlon Brando), we find a disheveled captain Willard (Marin Sheen) in a depressing Saigon hotel. Most striking about this scene, however, isn’t the physical state of Willard himself, but rather his distressed psychological state resulting from his past deployment in Vietnam. In what is inarguably a fascinating sequence, a gradual fade-in revealing a serene jungle landscape is accompanied by a strange acousmatic pulsation that slowly reveals itself as a synchretic track associated with a helicopter that passes through the frame in slow motion. A thick yellow smoke wafts in the foreground in real time. This odd disjuncture between slow and natural motion is amplified via the diegetic sound of the slow whirling blades of the helicopter and the uncertain sounding of notes on a guitar culminating in the landscape unexpectedly becoming engulfed in flames as Jim Morrison assuredly sings, “This is the end.” As the song makes its clear declarations the camera begins a slow pan and the image itself is completely obscured by the thick yellow smoke creating both a scene of certain destruction forecast by the music yet disallowing any sense of visual clarity. Without yet establishing a particular locus of experience, one already gets the sense that this is indeed a mental and wholly subjective projection. The scene exists in a seemingly virtual or experiential time—a sort of Bergsonian durée—far removed from any objective and measurable temporality as the slow motion merges with natural time. This intuition is validated by the superimposition of a close up of captain Willard’s face, outwardly lost in thought, as well as a slowly revolving ceiling fan over the smoldering forest ultimately solidifying into an opaque shot of the ceiling fan by way of a sound bridge linking the helicopters to the fan itself. What we have, in effect, is a perfectly orchestrated glimpse into the unstable and confused psychological state of our protagonist and, more complexly, a means of understanding the world through this character. Both sound and image coalesce and spectatorial expectation is dialectically supported and negated. Our vision and experience is similarly altered to match the confused and damaged psyche of this soldier and even our aural understanding is twisted as what we experience as the pulsating rhythm of spinning helicopter blades becomes the point-d’écoute of our protagonist warping the sound of a ceiling fan into the backdrop of this horrific memory (or implied memory). Furthering this seemingly irrefutable positioning of spectator within the protagonist’s subjectivity is the faux, split-diopter double exposure of close-up on Willard and, simultaneously, Willard’s point-of-view. By allowing this strange double exposure to overlay the destruction, the scene itself becomes a tripartite and fractured reflection of Willard with the spectator playing the role of observer and observed, in essence, Willard himself. While this opening scene illustrates some of the strictly formalistic ways of constructing subjectivity within film, it does not address the more complex and problematic notion regarding Willard’s subjective place in the world both within the narrative discourse and outside the confines of the screen. In The Dialogical Imagination, Mikhail Bakhtin acknowledges the often problematic false dichotomy between the distinctly formal and the distinctly ideological suggesting that “more often than not, stylistics defines itself as a stylistics of ‘private craftsmanship’ and ignores the social life of discourse outside the artist’s study, discourse in the open spaces of public squares, streets, cities and villages, of social groups, generations and epochs” (259). In essence, rather than understanding a complex work (the novel in Bakhtin’s case) as a hermetic construction, one must consider that the work and, indeed, the artist are inherently socially constructed subjects “taking shape at a particular historical moment in a socially specific environment [brushing up] against thousands of living dialogic threads woven by socio-ideological consciousness” (276). Shifting this conception beyond the confines of the novel, our understanding of Willard as subject becomes a complicated refraction of a particular way of being in the world. In essence, regardless of Willard’s complicated and conflicted relationship with war itself (as is represented by his fractured psyche), he is simultaneously constructed and incorporated within a culture that has historically been driven and even defined by war and acts of aggression. Just as the colonial subject unwittingly wears the scar of subjugation, so too must the aggressor, the colonizer, the racist, or those socially constructed within a culture largely defined by this kind of violence never entirely shed this mode of being even when operating from a place of detached authority, as being in the world places one in constant discourse with the victimized Other. At this point we can briefly revisit the way in which the viewer is given seemingly unrestricted access to Willard’s subjectivity in an arguably more nuanced and complex fashion than previously discussed. Coppola’s incorporation of voice over narration affords a privileged position for the spectator and effectively allows an immediate access point into Willard’s subjective state at any given moment. This aural entry into his psychological state however, should additionally be read in relation to the optical. Given the predominance of Willard’s frequent internal monologue, one must inevitably concede that the visual itself must, at times, reflect our protagonist’s subjective state. Bolstering this observation, we are given frequent point-of-view shots in which characters speak directly to the camera, not as a means of breaking the fourth wall but rather as if the spectator is looking directly through Willard’s eyes. The infamous Do Lung bridge sequence is a particularly strong example of this as shot reverse shot becomes one of Willard’s point-of-view intercut with a close up of Willard’s response. The classic strategies of constructing character subjectivity within cinema (POV, internal dialogue, etc.) also typically include manipulating the very way the camera looks at the world, this becomes clear through the use of slow motion (as we have discussed in relation to the opening shot) and other unnatural effects. However, a particular way of seeing need not be articulated through exaggerated special effects or camera tricks. Herein lies the complex and totalizing aspect of the construction of subjectivity within this particular text. Coppola, perhaps unwittingly, not only allows us access to Willard’s psychological state, but additionally, his entire mode of being and a shared cultural subjectivity as the film unfolds. By taking into account the inconceivable lack of active and autonomous Vietnamese bodies, the film inadvertently makes visible the invisible. Those bodies that must, through the course of the narrative discourse, come into contact or be witnessed by the protagonist yet are largely absent from the text. The Vietnamese (both North and South) in this instance, exist in this particular work as background scenery and barely glimpsed subjugated bodies. We are made to unsee their place in the world and in the war. This, of course, belies any notion of objectivity, as ARVN, NVA, and Viet Cong forces, not to mention Vietnamese civilians, must indeed be heavily featured for any impression of objectivity to be relevant. Thus, their very absence as significant players points to an act of willed disappearance undertaken by the protagonist. Seeing through Willard’s eyes means unseeing the Other; he charges single-mindedly toward his mission’s objective already operating from a place of “cultural superiority.” Furthermore, in all its hectic irreverence, the war itself undergoes a process of beautification. Explosions, gunshots, and flares tear across the sky in a sort of spectacular fireworks display for the delectation of the eye seemingly at odds with an objective picture of warfare. Willard’s subjectivity rests as a filter on Vittorio Storaro’s lens. The tinted glasses of the conflicted soldier: infatuated with the raw power of war, blind to his/her own atrocities, yet gripped by a gnawing, free-floating guilt and fractured by the frenetic confusion of warfare. We are left then, within Willard’s conflicted state of being. War is hell, but this culturally specific hell is one that has its benefits, its unceasing call to “be all you can be,” a promise of unmitigated power. The invisible Other—as is made clear when we are exposed to Kurtz’s compound and his god like status—exists only in a subjugated role, always subordinate to the inherent superiority of the colonialist/neo-colonialist. This complicated way of constructing subjectivity in the film need not be understood as a conscious choice by the director but rather an effect of the process of subjectivization in play narratively and external to the text. It is not necessary to consider this as directorial intentionality but instead as a shared cultural subjectivity that seeps in through pen and lens and shapes the very essence of our protagonist. Robert Stam and Ella Shohat point out that “to a certain extent, a film inevitably mirrors its own processes of production as well as larger social processes” (807) and, in this instance, Willard’s mode of being is indeed a refraction of the larger sociopolitical and ideological forces circulating and colliding in a subjectivizing process at work beyond the confines of the text. In a sort of extra-textual doubling, Francis Ford Coppola himself commented on his utilization of low cost Filipino labor used during the creation of the film (Shohat & Stam 807). Taking advantage of this power differential, Coppola, like Willard, is fundamentally constructed within a multiplicity of frameworks, yet cannot escape the incorporation of the neo-colonialist’s unseeing eye. We can perhaps expand on this notion of becoming within a neo or post-colonialist framework by superficially reversing our spectatorial position within the equation and “being” in the world as the unseen Other. In Ousmane Sembène’s 1966 masterpiece La Noire de… Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a young Senegalese woman, works as a nanny for a wealthy French couple in a newly post-colonial Senegal. No longer able to embody their colonialist role in Senegal, the couple returns to France bringing an excited Diouana with them. Diouana’s position in France however, becomes that of servant and her alienation and disaffection becomes unbearable. Sharing some similarities with Apocalypse Now in relation to the construction of subjectivity, Sembène allows unrestricted access to Diouana’s internal dialogue. Diouana’s inner dialogue alone, however, does not illustrate her ontological and phenomenological entirety. In order to grasp Diouana’s true experience and place in the world, her becoming post, or arguably, neo-colonial subject, we must take into account not merely her words but also the construction of the image as it shifts between Diouana’s memories of Senegal and her present experience in France. Of particular importance in this analysis is both camera movement and pacing. As Diouana becomes aware of the true state of her current mode of existence (as neo-colonial subject in the new France/Senegal relation), we are allowed a glimpse of her past in Senegal by way of a flashback. Particularly striking is the way in which Sembène imbues these memories with a vibrancy and energy wholly absent from Diouana’s life in France. Time seems to flow unceasingly from one shot to the next as the camera pans, tilts, and tracks through each frame following Diouana’s excited pace as she looks for and receives her job offer. The Senegalese score accompanying this memory projects a certain cultural specificity that immediately serves to contrast the periodic European musical backdrop that functions as a reminder of Diouana’s growing alienation in France. In contrast, Sembène captures Diouana’s life in France in a series of nearly static, long, dragging takes in which the stark white walls of the apartment enclose the dark Diouana in a prison of otherness. Her only link to Senegal, a decorative mask she offered to her “captors,” hangs alone on a broad, barren wall existing as a reminder of both her current objectification and alienation and, conversely, a happier past life. The temporal variance between past and present points to a subjective, experiential time in which the past is bound in the present and the present bound, in turn, to the past. Speed, energy, possibility; Diouana’s memory of the past—necessarily constructed and remembered in a specific, subjective, present—becomes one of unlimited potentiality. Diouana’s seemingly open future is a refraction of Senegal’s newly gained autonomy but her present state is one of boundaries imposed through an invasive neo-colonialist discourse. In discussing his conception of the “time image,” Deleuze notes, “The rise of situations to which one can no longer react, of environments with which there are now only chance relations, of empty or disconnected any-space-whatevers replacing qualified extended space. It is here that situations no longer extend into action or reaction in accordance with the requirements of the movement-image” (Deleuze 195). Deleuze’s time image may be an apt descriptor when discussing this film as, indeed, it exhibits a powerful felt time unshackled from and effectively freezing the force of motion, yet, to truly understand the complex construction of the film, one must return briefly to the precursor of the time image, specifically Henri Bergson’s durée, and more specifically, his conception of the virtual image. Bergon’s virtual, which is part and parcel of our lived experience, does not merely function as a mirroring of the present in the form of memory but additionally incorporates a second, simultaneously operating, string which projects toward the future (King 67). It is this experiential existence, where past and future coalesce in the present, that is particularly interesting in the context of this film. As Diouana’s subjectivity is eroded and rebuilt through the unseeing eyes of her French “owners,” any process of further becoming is stifled, thus, this “pantomimic” or projected future string must itself double back to a frozen present. Sembène’s steady, long takes and the eventual and stark absence of Senegalese music, become what can only be understood as a vision of the world through Diouana’s eyes: an increasingly stagnant durée creeping slowly toward a perpetual state of the present. Diouana’s French employers freeze her in this state of visible invisibility by refusing to even acknowledge the possibility of complex mental processes operating beneath her black skin. As our protagonist struggles to exist, her employers see only an exotic object, machinelike, functioning without autonomy, devoid of a unique subjectivity. It is only through a final act of violence against the self, that Diouana can exert her selfhood against an all-encompassing othering force. Sembène’s temporal and aural manipulation allows us access to Diouana’s ossifying subjectivity in a way both subtle and unflinchingly violent. If Apocalypse Now functioned from a position of authority in which we are made to unsee the Other, La Noire de… conversely forces us to see through Diouana’s eyes and become the invisible, desperately screaming to prove our existence. ReferencesApocalypse Now. Dir. Francis Ford Coppola. Zoetrope Studios, 1979. Bakhtin, M.M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981. Print. Deleuze, Gilles. “From Cinema II: The Time-Image.” Critical Visions in Film Theory. Eds. Corrigan, Timothy, Patricia White & Meta Mazaj. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2011. Print. Dream of a Rarebit Fiend. Dir. Edwin S. Porter. Edison Manufacturing Company, 1906. Grandma’s Reading Glass. George Albert Smith. George Albert Smith Films, 1900. King, Homay. Virtual Memory: Time-Based Art and the Dream of Digitality. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015. Print. La Noire de…. Dir. Ousmane Sembène. Filmi Domirev, 1966. Münsterberg, Hugo. “Why We Go to the Movies.” Critical Visions in Film Theory. Eds. Corrigan, Timothy, Patricia White & Meta Mazaj. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2011. Print. Shohat, Ella & Stam, Robert. “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle over Representation.” Critical Visions in Film Theory. Eds. Corrigan, Timothy, Patricia White & Meta Mazaj. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2011. Print. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Film & Media |