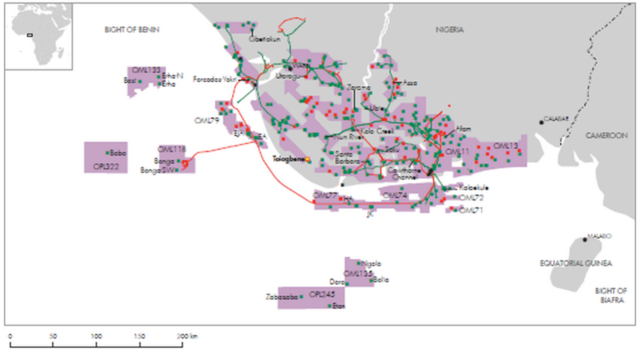

The Resource Curse in Nigeria: Comparing the Security of Offshore and Onshore Oil ProductionThe Case of NigeriaWith a population of about 173 million people, Nigeria is Africa’s largest country (World Bank). It is also the leading oil exporter in Africa, with the largest natural gas reserves in the continent. With such abundant natural wealth, Nigeria has the potential to build a prosperous economy and reduce poverty, though some areas of the country are still plagued by poor standards of living. Even the communities that sit on top of valuable resources remain impoverished, as little oil money trickles down to the general population. This lack of reimbursement has lead some people have turned to looting and attacks on oil facilities in order to turn a profit or show their discontent with the government. A Brief History of Oil Exploration in NigeriaThe British began conquering different parts of Nigeria in the early 19th Century, with present-day Nigeria taking form in 1914 (Federal Republic of Nigeria Embassy). After a ‘struggle for freedom’ between 1922 and 1959, Nigeria became a self-governing state on October 1st, 1960 and established a Republic with a parliamentary system that was in place until 1966 (FRN Embassy). A military coup in January 1966 marked the beginning of a succession of military governments that lasted until 1979, when power was once again handed to a civilian government (FRN Embassy). This was followed by yet another series of changing power and military coups, until 1999 when the current Presidential System of Government was initiated (FRN Embassy). The 5th consecutive national elections took place in April 2015 and marked the most peaceful elections in the country to date (World Bank). According to the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), oil was first discovered in Nigeria in 1956 at Oloibiri in the Niger Delta, after nearly half a century of exploration. Since then, corporate politics have intersected with successive dictatorships that assumed oil resources and leased them to multinational oil corporations such as Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, and ExxonMobil. In 1970, the end of the Biafran war coincided with the rise in worldwide oil prices, allowing Nigeria to gain riches almost instantly. In 1971, Nigeria joined the Organization of Petroleum Exploration Companies (OPEC) and established the NNPC in 1977, a state-owned company that is involved in all stages of the petroleum value chain: upstream (exploration and production), midstream (processing and transportation), and downstream (marketing and refining) sectors. It was during this time that National Oil Companies began to appear across OPEC member states (PENGASSAN).While these companies often took direct control of production in their host countries, the Multinational Oil Companies (MNOCs) in Nigeria were only allowed to operate under Joint Operating Agreements (JOA), which specified the role of the Nigerian government in the operations. The purpose of a JOA is to prevent monopolization by allowing each party to retain some form of separate operation (PENGASSAN). JOAs are still dominant in Nigeria, accounting for over 90% of the country’s total oil and gas production (PENGASSAN). As offshore operations become increasingly popular, there has been a shift from JOA regimes to Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs), the main difference being that the government is paid in cash instead of crude oil (PENGASSAN). This became necessary because JOA regulations not smoothly transfer to offshore operations and with resources dwindling, funding became precarious for the government. The Major Players: Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, and ExxonMobilAccording to Royal Dutch Shell’s most recent investors’ handbook (published in 2011), the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd (SPDC) operates a joint venture that holds over thirty Niger Delta onshore oil-mining leases of which Shell holds a 30% interest. As of 2011, Shell production in Nigeria reached over 1 million barrels per day (bp/d), accounting for just under half of Nigeria’s total daily production, which currently stands at about 2.4 million bp/d (Shell). Offshore, SPDC holds interest in 6 shallow water offshore leases as well as 100% interest in 3 deep-water blocks, which are governed through PSCs, including the Bonga field, located 74.5 miles offshore (Shell). The map below from the investors’ handbook shows all Shell concessions in Nigeria. Chevron is the second-largest oil producer in Nigeria and one of its largest investors (Chevron). The corporation holds 40% interest in 9 onshore concessions and 9 deep-water blocks (though only three are in operation), with offshore interests ranging from 20-100% ownership (Chevron). According to Chevron’s 2015 Nigeria Fact Sheet, their net daily production is approximately 240,000 barrels of crude oil, 236 million cubic feet of natural gas and 6,000 barrels of liquefied petroleum gas. Over half of its crude oil comes from the deep-water Agbami Field, which lies 70 miles off the coast of the central Niger Delta and spans roughly 45,000 acres with a water depth of 4,800 feet (Chevron). The field also produces 15 million cubic feet of natural gas per day through 8 producing wells, though Chevron holds only 67.3% interest (Chevron). ExxonMobil’s Mobil Producing Nigeria (MPN) operates exclusively offshore, operating over 90 offshore platforms with roughly 300 producing wells at a capacity of over 550,000 bp/d (ExxonMobil). MPN owns 40% of production under a JOA with the federal government of Nigeria (ExxonMobil). A series of projects are currently underway to boost current production levels to 1 million barrels per day. The company has initiated the East Area Additional Oil Recovery project in hope of extending field life and increase oil recovery, as well as The Natural Gas Liquids project to begin LNG production (ExxonMobil). The Google Maps below shows Nigerian concession areas as of 2015. The map accounts for Mobil, Chevron, Elf, and Agip concessions, though Shell concessions were too extensive to be shown clearly on the same map. Chevron blocks are outlined in red and ExxonMobil in gray. Oil ProtectionDue to increased militant attacks on the oil industry, companies began to seek “protection work” in recent years in hopes of protecting their operations (World Bank). These “private armies” were necessary because of the failure of Nigerian military forces to contain the threats, though they have proven to be ineffective themselves. These groups are often underpaid, poorly trained, and ill equipped, making them largely unsuccessful in deterring guerrilla attacks (World Bank). Though they are officially a subset of the Nigerian police force, the personnel view themselves as employees of the MNOCs, who substantially supplement their incomes (World Bank). This dual power enforcement adds to the uncertainty and inefficiency of the protective groups. MNOCs have also been known to pay off militant groups in order to protect their assets. According to a 2008 World Bank analysis of conflict in the Niger Delta, the contracts between companies and militant groups have either been a) direct, as in the case of “surveillance contracts” given to locals to protect oil infrastructure, or b) indirect, or rather ransom payments or pay-offs to prevent attacks. Though it is often cheaper to buy off militant groups than to repair damages, both these contracts reward and sustain violence in the Niger Delta (World Bank). While miles of ocean water provides its own form of protection, protecting the world’s biggest marine industry and securing large water areas is extremely difficult. As the offshore oil and gas industry gains greater strategic and economic importance in light of global security concerns, offshore installations become more attractive for attacks. While Nigerian pirates in the Gulf of Guinea are currently the most active in the world (surpassing Somali pirates), MNOCs in the Gulf mostly operate with this threat in mind. An effective security system must be able to: secure miles of open water, detect small boats and swimmers that are undetectable by radars, withstand harsh weather conditions, and run 24-hours a day, year round (HGH). While attacks on onshore drilling sites and oil transportation are becoming more difficult due to increased security, offshore platforms remain vulnerable (Harel). According to a 2013 Chatham House report, attacks on petroleum vessels are well choreographed, and hijackers usually have accurate knowledge on their location and how to operate them. Attacked tankers are usually moored and therefore easily detected and boarded. While kidnapping is a major issue in the Gulf of Guinea, pirates and rebels launching attacks from Nigeria usually aim to steal cargo, equipment or valuables from the vessel (Chatham House). The crew is usually held while the cargo is moved to smaller vessels that will resell the petroleum onshore. It is estimated that 40% of Europe’s oil imports must travel through the Gulf of Guinea each year, making offshore attacks a serious concern (Chatham House). Growing Tensions in the Niger Delta: MEND and Boko HaramA 2013 report published in the New York Times found that an estimated 100,000b of oil were stolen in Nigeria each day (Nossiter). This added up to $10.9 billion of lost oil revenues between 2009 and 2011, with an added average of 1,000 people killed each year in result of oil conflict (Nositter). Though the majority of oil crime was centered around “bunkering,” or siphoning oil from pipes on land or under water and transferring it to barges in the Gulf of Guinea, it has recently evolved into increasingly violent attacks (Red24). According to the Red24 2013 Threat Forecast, oil crimes are becoming increasingly well coordinated and ambitious in their operations, attacking crewmembers and commercial shipping vessels. The first insurgent group to receive international attention was the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), which launched a non-violent campaign in 1990 against the Nigerian government and Royal Dutch Shell in response to the environmental degradation and economic collapse in the Ogoniland, an area of the Niger Delta (Hanson, Council on Foreign Relations). The movement ended when Shell ended production in Ogoni in 1993, though MOSOP leader Saro-Wiwa and eight other members were executed by the military regime in 1995 (Okafor). Subsequent groups were organized at clan levels, though most quickly dismantled after carrying out sporadic attacks to extort short-range funds (Hanson). The largest and most established Nigerian militant group in the energy sector calls itself the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and began their fight against MNOCs in the Niger Delta in 2006 when they claimed responsibility for the capture of four oil workers (Hanson). With no clear leader or structure, MEND is more of an umbrella organization linked to smaller rebel groups than an exclusive body (Ebienfa). Between 2006 and 2007, the group’s kidnappings and bunkering reduced oil output in the Delta by roughly 1/3rd, disrupting the oil supply of the world’s 15th largest oil producer (Hanson). Made up of mostly young men in a decentralized structure, the militants claim to be fighting in opposition to the environmental degradation caused by the oil industry and the lack of benefits the community has received from its resource wealth (Ebienfa). Oil instillations and spills have severely damaged the regions once-booming fishing industry (National Geographic). Despite the Joint Operation Agreements that all MNOCs must agree to, little of this money trickles down to the Delta’s 30 million residents. Besides oil bunkering, MEND and smaller militant groups seek profit from kidnapping oil workers and threatening MNOCs who are willing to pay militant leaders to ensure “security” of oil installations (Hanson). However, instances when MEND made specific demands have failed to generate substantial compensation. In 2006, MEND demanded that Shell pay $1.5 billion reimbursement for polluting the Niger Delta (Hanson). Negotiations between MEND and the government were interrupted with 15 MEND militants were killed by the Nigerian military while on their way to negotiate the release of a kidnapped Shell worker, resulting in more frequent and destructive MEND attacks (Hanson). After increasingly serious attacks, including the 2008 on Shell’s deep-water Bonga oilfield, a peace deal was signed in 2009 between MEND and the Nigerian government (Ebienfa). This, along with the rise of Islamic extremism in the north guided by Boko Haram, led to a decrease in onshore attacks. Many low-level ex-militants turned to piracy as a source of short-term wealth. In his 2007 book Brave New War, John Robb, a former USAF pilot in special operations, outlines the three main tactics used by Nigerian guerillas when attacking Shell offshore oil installations. They include:

Swarm-based maneuvers require little equipment and allow the guerillas to move much faster than navy battleships or large coastguard boats. This is an advantage not held on land, where security forces have the ability to move much faster. Advancements in technology have also benefitted the rebels, though relatively little gear is needed to undertake serious offshore damage. The Boko Haram uprising in 2009 turned attention away from the Niger Delta and towards the north when the Islamic extremists began attacking police stations and government buildings in Maiduguri (Chothia). The group has since carried out bombings and attacks on churches, busses, bars, military barracks, and even the UN headquarters in Abuja (Chothia). In April 2014, the group gained international condemnation when they abducted over 200 schoolgirls from Chibok town in Borno state (Chothia). Operating in northern and central Nigeria and preaching Islamic supremacy over environmental conservation, Boko Haram has not yet targeted Nigeria’s oil industry, which is predominately focused in the south. It has, however, turned governmental and MEND attention away from the oil industry. Representing the Christian south, MEND leaders are increasingly concerned about their own safety and the well being of their fellow Christians in the north. As recently as, July 2015, ex-militant leaders of MEND met in Yenagoa to discuss the activities of President Buhari’s administration, saying that it needed to move faster to tackle Boko Haram, who has been renewing attacks and killing hundreds of people (Folaranmi). Such attacks have presently taken international attention away from the environmental and economic welfare of the Niger Delta.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Political Science |