John Stuart Mill's Solution to the Problem of Socrates in the Autobiography

By

2015, Vol. 7 No. 11 | pg. 1/2 | »

KEYWORDS:

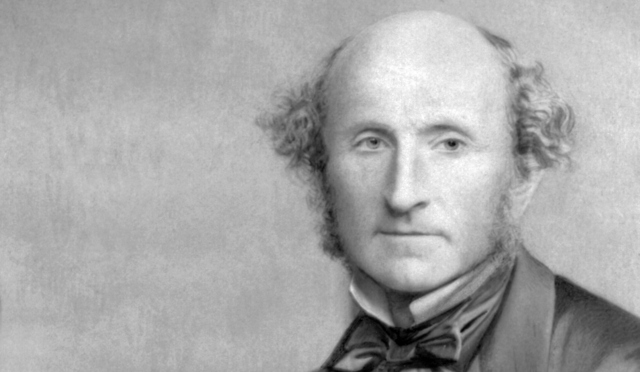

Ever since its posthumous publication, John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography has elicited reactions of primarily disappointment and confusion. Thomas Carlyle famously deemed the book the “autobiography of a steam-engine” (quoted in Levi 295) and readers since have generally agreed with his verdict. Leslie Stephen and Harold Laski argue that Mill’s Autobiography is “severely deficient,” (Levi 284) on account of its mechanical and emotionally sterile prose and its complete lack of details about any aspects of Mill’s life which are not obviously relevant to his philosophical and political careers. Mill does not even mention his mother in the Autobiography, and only indirectly mentions his siblings. Although it is dutifully referenced in biographies written about Mill’s life, the Autobiography itself continues to receive little critical attention. According to Kathleen Welch, the main characters in the Autobiography are the embodiments of philosophical essays that form sub-theses throughout the work (153-154), and this essay-like approach accounts for the general dryness of the Autobiography. I read Mill’s portrayal of his father, James Mill, as a treatment of what Friedrich Nietzsche calls the “Problem of Socrates.” Although Mill addresses Socrates in several of his essays, it is in the Autobiography that Mill approaches the father of Western philosophy from an angle that situates Mill in discourse with existential philosophers such as Soren Kierkegaard in addition to Nietzsche. The central conflict in the Autobiography is Mill’s struggle against depression during his early adulthood. Mill overcomes his depression by cultivating his emotions by reading poetry, which his father neglects during his son’s education. Furthermore, I intend to demonstrate that Mill portrays his depression as the consequence of the “Problem of Socrates,” and his recovery as his overcoming of the problem. Kierkegaard writes in Christian Discourses that he has “admired that noble, simple wise man [Socrates] of ancient times,” that his “heart too has beat violently as that of the young man when he conversed with him, and the thought of him has been the enthusiasm of his youth and filled my soul to overflowing. I have longed for conversation with him as I never longed to talk with any man with whom I have talked..." (245). In On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, Kierkegaard again applauds the character of Socrates—but here, he also criticizes Socratic methodology. The Socratic Method is a form of discussion or debate in which an inquirer will ask a series of questions as to stimulate critical thinking about a particular subject. Plato’s Socratic Dialogues usually conclude with Socrates unravelling his opponent’s beliefs or assumptions about something, thereby exposing his ignorance. In Plato’s Dialogues, Socrates is motivated to his questioning by a desire to overcome his ignorance by the only valid means—reason—and to arrive at a universal definition of virtue with which he may live in accordance (In Euthyphro 5). For Socrates, living virtuously is the purpose and meaning of existence. Kierkegaard argues that Socrates’ commitment to reason as the only means of knowing virtue and being virtuous drives him to conclusions that are impractical and even negative towards life (In On the Concept of Irony 185). Socrates refuses to compromise his logical, though impractical, conclusions for the sake of delivering a philosophy by which people can live. As a consequence, the Socratic Method in its application is negative and polemical, since it seeks to deconstruct and expose the ignorance of all ideas and beliefs which are not strictly rational—and no meaningful beliefs or ideas held by real, living people are strictly rational. Kierkegaard writes that the Socratic Method is “a position that continually cancels itself; it is a nothing that devours everything, and a something one can never grab hold of, something that is and is not at the same time, but something that at rock bottom is comic” (On the Concept of Irony 131). Socratic Method tends to never arrive at positive, practical principles—values about how one should live. Rather, it merely deconstructs that which others already believe to be true. Nietzsche agrees with Kierkegaard that the Socratic Method undermines meanings and values rather than provides them. Like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche admires the disciplined and forceful personality of Socrates. Yet for Nietzsche, the Socratic Method is not merely the questioning of life, but even the negation of it. Nietzsche describes all this in a section in Twilight of the Idols entitled “The Problem of Socrates.” “Concerning life, Nietzsche writes, “the wisest men of all ages have judged alike:it is no good. Always and everywhere one has heard the same sound from their mouths -- a sound full of doubt, full of melancholy, full of weariness of life, full of resistance to life. Even Socrates said, as he died: “To live -- that means to be sick a long time: I owe Asclepius the Savior a rooster” (39). Nietzsche reads Socrates’ ascetic lifestyle and adherence to abstract “forms” as the consequence of the Greek philosopher’s disgust towards life. According to Nietzsche, the pre-Socratic Greeks celebrated life in fatalistic terms, affirming their suffering as essential to life as is joy (The Birth of Tragedy 44, 112). Socrates, who is ugly both in soul and in appearance, projects his ugliness onto the world. He subsequently invents otherworldly forms of beauty that exist independently from the “ugliness” of nature, which is really his own ugliness and weakness. Furthermore, Nietzsche regards Socrates’ association of happiness with his “virtue” as a baseless assumption: “I seek to comprehend what idiosyncrasy begot that Socratic equation of reason, virtue, and happiness: that most bizarre of all equations which, moreover, is opposed to all the instincts of the earlier Greeks” (Twilight of the Idols 41). From his earliest works, Nietzsche argues that the “genre” produced by the Socratic Method, that being the dialogue, further reflects the degeneration from pre-Socratic to Socratic philosophy (The Birth of Tragedy 35). The epic poetry and tragedy of the pre-Socratic Greeks denotes a strong culture that embraces the chaotic emotive forces of life (The Birth of Tragedy 37). On the other hand, the Socratic Dialogue, a systematic genre intended for the delivery of logical arguments, reflects an Apollonian culture which has abandoned art grounded in life for otherworldly knowledge accessed alone through reason (The Birth of Tragedy 38). Thus, Nietzsche advocates for a return to a pre-Socratic, Dionysian kind of art, which engages the rich sensuality of human experience and affirms life, rather than denying life and appealing instead to austere, otherworldly philosophical reason. Similar to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, Mill celebrates the personality of Socrates. Linda Raeder writes that “both the Mills preferred to regard themselves as disciples of the pre-Christian philosophers, especially the Greeks” (14). Mill directly celebrates the character of Socrates most notably in his essay On Liberty, writing that mankind “can hardly be too often reminded, that there was once a man named Socrates. . . Born in an age and country abounding in individual greatness, this man has been handed down to us by those who best knew both him and the age, as the most virtuous man in it... we know him as the head and prototype of all subsequent teachers of virtue, the source equally of the lofty inspiration of Plato and the judicious utilitarianism of Aristotle. (106) Clearly, Mill’s association of his father initially presents James Mill as a Socrates figure in a very positive light in the Autobiography. Mill writes that Mill writes that

In celebrating Socrates, Mill emphasizes his status as a great teacher, which is also how he characterizes his father. On his education, Mill writes that it was his father’s

John Stuart Mill’s early education seems to center on the Socratic Method. James Mill educates his son by questioning him about his readings, guiding his son towards rational conclusions by means of syllogisms. This teaching-strategy recalls the concept of Socratic Irony (as defined by Kierkegaard) in which an inquirer will ask questions to encourage a student to arrive at a conclusion which the inquirer already knows. Most significantly, Mill states that “the first intellectual operation in which [he] arrived at any proficiency” is the polemical dissection of faulty arguments, the purpose (problematically so, according to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche) of the Socratic Method. Mill does not mention any “positive principles” about the world that he acquired from his Socratic dialogues with his father. He only praises the Socratic Method as a teaching-tool for exposing the logical fallacies of “false” ideas. Mill’s “first proficiency” foreshadows Mill’s impending intellectual crisis which takes place later in the Autobiography. In his account of his religious upbringing, Mill clearly portrays his father not merely as a Socrates-like teacher, but also as Socratic in his moral personality. Mill writes that his

James Mill’s rejection of religion as counter-productive to “genuine virtue” strongly echoes Socrates’ rejection of the pagan gods of Athens in pursuit of living the virtuous life. Mill directly relates his father’s moral convictions to those of Socrates, writing that they

Like Socrates, James Mill aspires to definitive virtues which exist outside of an established, traditional religious system by means of rational philosophy. Fittingly, James Mill educates his son to adopt his Socratic approach to religion. Mill writes that it

The manner in which James Mill educates his son to disbelief in god— by questioning his son until Mill realizes the contradiction of believing in an uncreated god who is the creator of everything—strongly resembles the Socratic Method which James Mill employed in his son’s general education. Mill writes that “I am this one of the very few examples, in the country, of one who has, not thrown off religious belief, but never had it: I grew up in a negative state with regard to it. I looked upon the modern exactly as I did upon the ancient religion, as something which in no way concerned me” (30). Mill’s education left him not prejudiced, but rather indifferent, towards religion, since he was taught to not believe in God on rational grounds. James Mill employs the Socratic Method to polemically prove to his son the fallacy of God’s existence leaves his son in a “negative state with regard to it.” The Socratic Method neither justifies the hatred exhibited by James Mill, nor does it truly disprove the existence of God; it merely identifies the flawed logic of the most popular apologetic arguments for the existence of God, and leaves Mill with no belief for or against. Consequently, John Stuart Mill in the Autobiography seeks to neither disprove God to his contemporaries, nor to adopt another active position about God’s existence; religion simply does not concern him. The Socratic Method neither affirms convictions nor erects new ones; it merely leaves one in a “negative state.” It is this “negative state” which ultimately brings John Stuart Mill to the brink of mental collapse in “Chapter Five” of the Autobiography. Titled “A Crisis in my Mental History,” this chapter is the most distinct in the entire work. The preceding and following chapters depict Mill’s education, his career with the East India Trading Company and his position in parliament, as well as his scholarly endeavors. The fifth chapter, on the other hand, is introspective and almost confessional in its tone. At the beginning of the chapter, Mill firmly establishes that his depression is not the consequence of suddenly-acquired knowledge or the consequence of a traumatic event. Instead, it is the consequence of his emotional exhaustion caused by his gradual realization of the failure of his education. Mill writes that his education

Whereas his father seems intrinsically driven by his Socratic virtues to better society through the Benthamite cause, Mill cannot move on from the analytical exercises provided to him by his father, and take up his role as a political philosopher in equal fashion. Mill writes that his education, “which was wholly his [father’s] work, had been conducted without any regard to its possibility of ending in this result... the failure was probably irredeemable, and, at all event, beyond the power of his remedies” (95). Janice Carlisle argues that the disparity between Mill’s “bookish” devotion to philosophy and his career with the Benthamite cause and the East India Trading Company results in an existential crisis; the former does not support the latter (126, 135).Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Philosophy |