|

From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 4 NO. 2 Divisive Economic Device? Understanding China's Choice to Create a Sovereign Wealth Fund

By Felicty M. Yost

Cornell International Affairs Review

2011, Vol. 4 No. 2 | pg. 2/2 | «

One might also expect CIC to acquire strategic holdings if it were purposed to be a foreign policy tool. In section one is a chart of CIC's holdings as most recently reported to the US Congress. First, it is worth noting that China has refrained from investing in military and defense technology. Despite being a lucrative sector in the American economy, she has respected that this would be a suspicious investment in the eyes of most Americans. Second, one will note the numerous holdings that are actually purchased through a third body. This represents an effort on the part of China to distance herself from direct interaction with the corporation in which it seeks holdings.

Lastly, it is necessary to address the commonly cited argument that China is seeking stakes in America's most influential firms to usurp the country from the insideout41. The problem with this argument is that America's most powerful firms also happen to be the most worthy of investment. It makes sense that China would invest in equities and natural resources because these types of firms tend to have the highest and quickest paying returns. As shown in section one, at least part of China's intention in CIC must be to earn high and fast payouts. Investing in America's strongest industries, finance and natural resources, proves to be the best path to this goal.

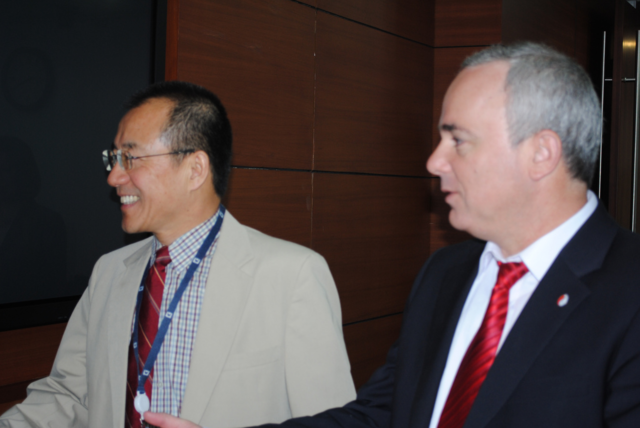

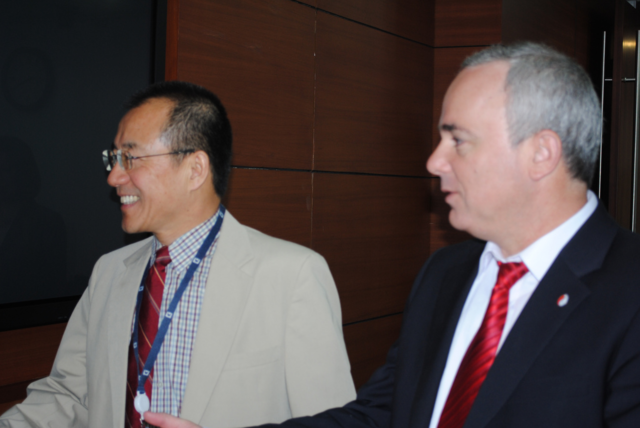

Gao Xiqing, the Vice Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at CIC, meets with members of Israel's Ministry of Finance.

The third reason CIC should not be classified as a foreign policy tool is because she has overtly declined voting stakes in her investments. One of the most frequently cited alarmist arguments is that CIC will win voting stakes in the companies in which it invests. The argument asserts that through a bottom up mechanism, China will gain control of these companies, and by extension the U.S. government42.

Yet, China to date, has declined all voting stakes in its investments. The most public instance of this was CIC's decline of a board seat in Morgan Stanley, despite owning a 9.9% stake in the company, the second largest stake in the company overall43. Winston Wenyan reported that the fund was "not really looking for voting rights or control but [was] trying to take advantage of surging asset values in China and depressed valuations here in the U.S."

He continued to explain that the Chinese "like minority stakes, so as not to raise the ire of politicians in Washington."44 A voting stake is clearly not the game China is hunting. Wenyan's observation also supports part-one conclusions that China is intent on raising capital quickly.

The last way CIC might act, if it were a foreign policy tool, would be to use its stakes to lobby the U.S. government. Because of the protests against CIC investing in American institutions at its conception in 2007, such blatant action on the part of CIC would be untactful. The Chinese government and CIC officials are certainly aware that such outright action would never go un-protested. But arguing that these leaders are competent is not proof enough to dispel this theory. In fact, there is no evidence to be found about this claim.

It is probable that if CIC were able to lobby the US government through one of its acquisitions, they would do this as surreptitiously as possible45. American policy, however, has remained steadfast towards Chinese interests, and so it seems unlikely that CIC is using its powers in this way, or if it is, they are quite ineffective.

In total, it is unlikely, but not completely determinable, that CIC is a foreign policy tool. While the first two proposed explanations for CIC's creation, profit maximization and bureaucratic politics, provide more resolute explanations, this third explanation proves exceedingly hard to negate due to limited information. The great question remains: even if CIC was created as a tool, could it threaten the US? The arguments of Kirchner, Drezner and Cognato dispel this thought. I believe a softer coercion is more likely.

Just by the nature of investing $1.4 trillion in the US economy means the CIC has a measure of soft power, as it has obtained stakes in 60 of some of America's most important industries46. We cannot discern whether soft power was a specified goal for the creation of CIC, or if China's leaders even recognized in 2007 that it would gain such great soft power. It is evident that CIC is now aware of its current and future source of soft power thanks to its investments in American equities by some of the top leadership's recent press-statements.

China has credited herself as being the stopgap between economic failure and the U.S. and she will verbally recognize her economic importance to the United States. China's continued investment in the U.S. and exportation of cheap goods to maintain the high volume of U.S. dollars that flow into China show the soft-power importance that Chinese investments and exports have for the U.S. In the CRS report for Congress published on August 15th, 2008, it was argued that Chinese soft power was augmented by her investment in Morgan Stanley when the stock was plummeting47. This shed a heroic light on CIC and China as an investing agency in general. Since then the American government has turned to China as a potential stable investor, most notably in U.S. bonds.

China's strength throughout the financial crisis may be another source of soft power for the country as a sound investment body that can lend legitimacy and stability to an industry. Gao Xiqing was reported saying "The US economy is built on the support, the gratuitous support, of a lot of countries. So why don't you come over and … I won't say knowtow, but at least be nice to the countries that lend you money."48 In this way, China benefits from enlarging the intersection between the economic and the political as it begins to take on an image of a quickly growing investment body, a rarity in these economically hard times.

As the concentration of power in the world system comes to center more on economic growth, the perception that such growth emanates from China is exceedingly important, and positions her more centrally as a source of power within the system. CIC only works to promulgate this image as an investment body of endless reserves. It was not until after the financial crisis that such articulations like the one cited above by Gao were uttered. In fact, the assumption by both investors and receivers was that if any type of power would flow from CIC, it would be due to investments in technology and natural resources49.

Perceived as an illegitimate way to consolidate power within the international system, China adamantly insisted that the intention of the CIC was purely profit maximization of forex holdings50. Influencing American foreign policy by reminding the U.S. government of the debt China owned, is perceived by the international community as more legitimate diplomacy because the interests of the two states have become "aligned."

"It has been cited that holding these forex reserves costs China $100 billion a year."

The conclusion to draw from this study of CIC's effect on foreign policy relies on the conclusions developed in section three: CIC is a way for China to continue economic growth because growth in China is recognized as the source for increased international attention. To tie all this together, it is helpful to think back to the proposals for CIC before it was formed. Zhou Xiaochuan, CCB governor, proposed that China create a super-sovereign wealth fund. He imagined the entity would be led by the IMF and would revoke the U.S. dollar as the dominant currency and replace it with several currencies including the Euro and the Yen. He also envisioned special drawing rights for states with large investments.

This proposal demonstrates several Chinese objectives: to secure an improved way to invest forex, to enhance her domestic growth by making the Yen a dominant currency of trade, and to use her economic power as a way to engage further with the international system51. Understanding this purpose of CIC provides an effective framework to also understand the Chinese oversight in the creation of BRIC. It explains Chinese stubbornness in maintaining a devalued currency in the face of US demands52. It also explains China's agreement with other BRIC economies to contribute to IMF reserves through the purchase of IMF bonds denominated in Special Drawing Rights that allowed China to modestly advance her goal of developing non-dollar currencies as reserve currencies53.

"Political might is often linked to financial might, and a debtor's capacity to project military might hinges on the support of its creditors" - Brad Setser54

What does it all ultimately mean? China has recognized her growing economic prosperity as a platform to command greater political power and to realize a greater number of her international desires. She seems to be using this power as means to engage further with the international system. Although China has not been able to demand outright for specific policy changes within the United States, she has been able to deter Washington from certain pursuits, such as involvement in North Korea55.

While we cannot make founded observations on the true intentions of China in relation to its purpose with CIC in the international system, we can conclude that it is currently not being used as a tool of foreign policy. This does not mean that China will not look to its SWF or simply to its vast forex reserves for policy coercion in the future. As CIC stands currently, the only foreign policy implications it represents are not divisive, but simply manifest, as its pure existence represents China's growing power in the international system. With that follows a certain legitimacy that simultaneously serves to delegitimize some of the United States' similar soft coercive powers. The bottom line is that China is becoming more politically important in the international system through her economic policies.

Felicity Yost is class of 2012 in the college of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University, studying French, Government and International Relations. Felicity has been involved with CIAR since the fall 2008 issue when she first started to become engaged in international politics. She currently maintains a strong interest in Chinese-US security relations.

- The term Politicized capitalism emerged at the transition of the Chinese political economy in the early 1980’ when Deng Xiaoping worked to develop a market economy around a planned sphere economy. Victor Lee and Sonja Opper charectorize the term in their chapter in “On Capitalism” as the following: “Politicized capitalism is a hybrid institutional order in which recombi- nant elements of central planning and state control combine and interact with emergent markets and private ownership forms. It comprises institutional ar- rangements patched together in ad hoc improvisations to address the needs and demands arising from rapid market-oriented economic growth.” Nee, Victor, and Richard Swedberg. On Capitalism. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2007. Print.

- Cognato, Michael

- Martin, Michael. 2008.

- Indications for this chart came from Cognato, Aizenman and Glick, and Shih.

- Cognato, Micheal.

- Cognato, Micheal.

- Cognato, Michael.

- Truman, Edwin

- SEC report, ending quarter December, 2009.

- Martin, Michael

- Somerville, Glenn

- Interview conducted with , director of agricultural investment at CIC, 12-09-2010.

- http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-10/14/content_11407514.htm

- Leonhardt, David

- The ‘norm’ for SWF’s is that capital flows directly from the ministry of finance, where forex reserves generally lie. The power and capital flows are therefore singular and less complicated than CIC’s because there is only one link and that is to the ministry of finance. Dani Rodrik, “The Social Cost of Foreign Exchange Reserves,” International Economic Journal 20 (September 2006); 115-130 Drezner

- http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/04/60minutes/main3993933_page2.shtml?tag=contentMain;contentBody

- As shown in the chart in section one, the PBOC does not sit under the same commission as the CIC. To finance the CIC, there was a cross bureaucracy exchange.

- Eaton, Sarah, and Ming Zhang

- Eaton, Sarah, and Ming Zhang

- Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation, p.14-22, 208-226.

- Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation, p.16.

- Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation, p.22.

- This may also be the reason American analysts are so quick to assert that these policies of China are a direct threat to US power.

- Cognato, Michael

- Bahgat, Gadat

- Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.”

- Eaton and Ming,

- Martin, Michael.

- Deduced from reporting of Eaton and Ming, Cognato, Aizenman and Glick, and Shih

- Shih, Victor. “Tools of Survival: Sovereign Wealth Funds of Singapore and China.” Geopolitics. 14.2 (2009): 300-375. Print

- Anderson, Eric.

- Anderson, Eric.

- Kirshner, Jonathan. “Sovereign Wealth Funds and National Security: The Dog that Will Refuse to Bark.” Geopolitics. 14.2 (2009): 305-315. Print.

- Drezner, Daniel. “Sovereign Wealth Funds and the (in)Security of Global Finance .” Journal of International Affairs. 62.1 (2008): 115-130. Print.

- Eaton and Ming declared the most transparent SWF to be Norway’s and the least transparent to be Singapore’s. This is attributed to their governing styles. In this instance, transparency refers to the ease with which one can discern the institutions holdings, intentions, and future investment strategies. In this paper transparency has the same definition.

- “China Investment An Open Book?.” 60 Minutes. CBS: New York, 06 04 2008. Television. 15 Nov 2010.

- Drezner, Daniel. “Sovereign Wealth Funds and the (in)Security of Global Finance .”

- Gurria, Angel

- Gurria, Angel

- The question of poor reporting and transparency in CIC’s investments can be explained by China’s governance style more confidently than it can be explained by malicious intentions of China. Kathyrn Lavelle explains in her article that SWF engagement style and transparency is highly correlated with the parent government’s governing style; therefore authoritarian regimes tend to be much more opaque in their investment strategies than their democratic counter parts.

- An argument most notably promoted by Larry Summers.

- Truman, Edwin and Lynch, David

- Martin, Michael. United States of America. China’s Sovereign Wealth Fund: Developments and Policy Implications . Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, 2010. Print

- “Morgan Stanley Posts loss; Sells Stake to China,” Harper, Christine. 12-19-2007, Bloomberg News. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a61Th6IcsbsU

- This view is asserted by Larry Summers in his article Funds that Shake Capitalist Logic, it is also shown in Micheal Martins essays for CRS from 2008 and 2010, and lastly in the CRS report entitled, Comparing Global Influence: China and the US Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade and Investment in the Developing World

- In this essay soft paper “soft power” has the sense of power that is otherwise completely political, that stems from a source other than pure governmental policy and is employed through means of pressure or influence.

- Lum, Thomas and Blanchard, Christopher and Cook, Nicolas and Dumbaugh, Kerry and Epstein, Susan, and Kan, Shirley and Martin, Michael and Morrison, Wayne and Naton Dick and Nichol, Jim and Sharp, Jeremy and Sullivan, Mark and Vaughn, Bruce United States of America. Comparing Global Influence: China and the US Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade and Investment in the Developing World. Washington DC: CRS, 2008. Web. 22 Nov 2010. .

- Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.” International Security. 34.2 (2009): 7-45. Print.

- Lum, Thomas and Blanchard, Christopher and Cook, Nicolas and Dumbaugh, Kerry and Epstein, Susan, and Kan, Shirley and Martin, Michael and Morrison, Wayne and Naton Dick and Nichol, Jim and Sharp, Jeremy and Sullivan, Mark and Vaughn, Bruce

- Jessy Wang reportedly stated, “The mission for this company is purely investment driven.”

- The reason this proposal was not adopted is because the United States protested strongly against it at the G-7 meeting in 2007.

- “In late March, Zhou Xiaochuan — the head of China’s central bank and the senior official who’s closest to Geithner — gave a speech suggesting that the dollar be replaced as the world’s reserve currency” Leonhardt, David. Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.”

- Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.”

- “At the end of a discussion with Lardy about the imbalances between the U.S. and China, I asked him what forms of leverage he thought the Obama administration had. “We have no leverage,” he replied. He then couched this slightly, saying that the administration could threaten the Chinese with trade barriers but that such threats weren’t likely to be very credible.”

- Leonhardt, David. “The China Puzzle.” The New York Times, (17-05-2009) 1-5. Print

Photos courtesy of:

Author

Felicity Yost is class of 2012 in the college of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University, studying French, Government and International Relations. Felicity has been involved with CIAR since the fall 2008 issue when she first started to become engaged in international politics. She currently maintains a strong interest in Chinese-US security relations.

Endnotes

- The term Politicized capitalism emerged at the transition of the Chinese political economy in the early 1980’ when Deng Xiaoping worked to develop a market economy around a planned sphere economy. Victor Lee and Sonja Opper charectorize the term in their chapter in “On Capitalism” as the following: “Politicized capitalism is a hybrid institutional order in which recombi- nant elements of central planning and state control combine and interact with emergent markets and private ownership forms. It comprises institutional ar- rangements patched together in ad hoc improvisations to address the needs and demands arising from rapid market-oriented economic growth.” Nee, Victor, and Richard Swedberg. On Capitalism. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2007. Print.

- Cognato, Michael

- Martin, Michael. 2008.

- Indications for this chart came from Cognato, Aizenman and Glick, and Shih.

- Cognato, Micheal.

- Cognato, Micheal.

- Cognato, Michael.

- Truman, Edwin

- SEC report, ending quarter December, 2009.

- Martin, Michael

- Somerville, Glenn

- Interview conducted with , director of agricultural investment at CIC, 12-09-2010.

- http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-10/14/content_11407514.htm

- Leonhardt, David

- The ‘norm’ for SWF’s is that capital flows directly from the ministry of finance, where forex reserves generally lie. The power and capital flows are therefore singular and less complicated than CIC’s because there is only one link and that is to the ministry of finance. Dani Rodrik, “The Social Cost of Foreign Exchange Reserves,” International Economic Journal 20 (September 2006); 115-130 Drezner

- http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/04/60minutes/main3993933_page2.shtml?tag=contentMain;contentBody

- As shown in the chart in section one, the PBOC does not sit under the same commission as the CIC. To finance the CIC, there was a cross bureaucracy exchange.

- Eaton, Sarah, and Ming Zhang

- Eaton, Sarah, and Ming Zhang

- Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation, p.14-22, 208-226.

- Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation, p.16.

- Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation, p.22.

- This may also be the reason American analysts are so quick to assert that these policies of China are a direct threat to US power.

- Cognato, Michael

- Bahgat, Gadat

- Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.”

- Eaton and Ming,

- Martin, Michael.

- Deduced from reporting of Eaton and Ming, Cognato, Aizenman and Glick, and Shih

- Shih, Victor. “Tools of Survival: Sovereign Wealth Funds of Singapore and China.” Geopolitics. 14.2 (2009): 300-375. Print

- Anderson, Eric.

- Anderson, Eric.

- Kirshner, Jonathan. “Sovereign Wealth Funds and National Security: The Dog that Will Refuse to Bark.” Geopolitics. 14.2 (2009): 305-315. Print.

- Drezner, Daniel. “Sovereign Wealth Funds and the (in)Security of Global Finance .” Journal of International Affairs. 62.1 (2008): 115-130. Print.

- Eaton and Ming declared the most transparent SWF to be Norway’s and the least transparent to be Singapore’s. This is attributed to their governing styles. In this instance, transparency refers to the ease with which one can discern the institutions holdings, intentions, and future investment strategies. In this paper transparency has the same definition.

- “China Investment An Open Book?.” 60 Minutes. CBS: New York, 06 04 2008. Television. 15 Nov 2010.

- Drezner, Daniel. “Sovereign Wealth Funds and the (in)Security of Global Finance .”

- Gurria, Angel

- Gurria, Angel

- The question of poor reporting and transparency in CIC’s investments can be explained by China’s governance style more confidently than it can be explained by malicious intentions of China. Kathyrn Lavelle explains in her article that SWF engagement style and transparency is highly correlated with the parent government’s governing style; therefore authoritarian regimes tend to be much more opaque in their investment strategies than their democratic counter parts.

- An argument most notably promoted by Larry Summers.

- Truman, Edwin and Lynch, David

- Martin, Michael. United States of America. China’s Sovereign Wealth Fund: Developments and Policy Implications . Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, 2010. Print

- “Morgan Stanley Posts loss; Sells Stake to China,” Harper, Christine. 12-19-2007, Bloomberg News. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a61Th6IcsbsU

- This view is asserted by Larry Summers in his article Funds that Shake Capitalist Logic, it is also shown in Micheal Martins essays for CRS from 2008 and 2010, and lastly in the CRS report entitled, Comparing Global Influence: China and the US Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade and Investment in the Developing World

- In this essay soft paper “soft power” has the sense of power that is otherwise completely political, that stems from a source other than pure governmental policy and is employed through means of pressure or influence.

- Lum, Thomas and Blanchard, Christopher and Cook, Nicolas and Dumbaugh, Kerry and Epstein, Susan, and Kan, Shirley and Martin, Michael and Morrison, Wayne and Naton Dick and Nichol, Jim and Sharp, Jeremy and Sullivan, Mark and Vaughn, Bruce United States of America. Comparing Global Influence: China and the US Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade and Investment in the Developing World. Washington DC: CRS, 2008. Web. 22 Nov 2010. .

- Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.” International Security. 34.2 (2009): 7-45. Print.

- Lum, Thomas and Blanchard, Christopher and Cook, Nicolas and Dumbaugh, Kerry and Epstein, Susan, and Kan, Shirley and Martin, Michael and Morrison, Wayne and Naton Dick and Nichol, Jim and Sharp, Jeremy and Sullivan, Mark and Vaughn, Bruce

- Jessy Wang reportedly stated, “The mission for this company is purely investment driven.”

- The reason this proposal was not adopted is because the United States protested strongly against it at the G-7 meeting in 2007.

- “In late March, Zhou Xiaochuan — the head of China’s central bank and the senior official who’s closest to Geithner — gave a speech suggesting that the dollar be replaced as the world’s reserve currency” Leonhardt, David. Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.”

- Drezner, Daniel. “Bad Debts: Assessing China’s Financial Influence in Great Power Politics.”

- “At the end of a discussion with Lardy about the imbalances between the U.S. and China, I asked him what forms of leverage he thought the Obama administration had. “We have no leverage,” he replied. He then couched this slightly, saying that the administration could threaten the Chinese with trade barriers but that such threats weren’t likely to be very credible.”

- Leonhardt, David. “The China Puzzle.” The New York Times, (17-05-2009) 1-5. Print

Photos courtesy of:

Save Citation » (Works with EndNote, ProCite, & Reference Manager)

APA 6th

Yost, F. M. (2011). "Divisive Economic Device? Understanding China's Choice to Create a Sovereign Wealth Fund." Cornell International Affairs Review, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1227

MLA

Yost, Felicty M. "Divisive Economic Device? Understanding China's Choice to Create a Sovereign Wealth Fund." Cornell International Affairs Review 4.2 (2011). <http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1227>

Chicago 16th

Yost, Felicty M. 2011. Divisive Economic Device? Understanding China's Choice to Create a Sovereign Wealth Fund. Cornell International Affairs Review 4 (2), http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1227

Harvard

YOST, F. M. 2011. Divisive Economic Device? Understanding China's Choice to Create a Sovereign Wealth Fund. Cornell International Affairs Review [Online], 4. Available: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1227

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

China and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that leads it has historically limited itself in regards to projecting power and inserting itself into international disputes and affairs. With the exception of its involvement... MORE»

The study examines the degree to which Xi Jinping has brought about a strategic shift to the Chinese outward investment pattern and how this may present significant political leverage and military advantages for China in... MORE»

This report examines the Chinese economic model, the potential for future Chinese growth, and the implications for Australia. An examination of factors that have contributed to the rise of the modern Chinese economy including... MORE»

China’s emergence as a key player in Africa, the impact of its presence and its challenges to traditional Western pre-eminence in African economies are among the hallmarks of the changing economic scenario in the twenty-first century. Beijing’s present-day engagement in Africa is not new: it has its roots in policies... MORE»

Latest in Economics

2020, Vol. 12 No. 09

Recent work with the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) has shown that a country’s productive structure constrains its level of economic growth and income inequality. Building on previous research that identified an increasing gap between Latin... Read Article »

2018, Vol. 10 No. 10

The value proposition in the commercial setting is the functional relationship of quality and price. It is held to be a utility maximizing function of the relationship between buyer and seller. Its proponents assert that translation of the value... Read Article »

2018, Vol. 10 No. 03

Devastated by an economic collapse at the end of the 20th century, Japan’s economy entered a decade long period of stagnation. Now, Japan has found stable leadership, but attempts at new economic growth have fallen through. A combination of... Read Article »

2014, Vol. 6 No. 10

In July 2012, Spain's unemployment rate was above 20%, its stock market was at its lowest point in a decade, and the government was borrowing at a rate of 7.6%. With domestic demand depleted and no sign of recovery in sight, President Mariano Rajoy... Read Article »

2017, Vol. 9 No. 10

During the periods of the Agrarian Revolt and the 1920s, farmers were unhappy with the economic conditions in which they found themselves. Both periods witnessed the ascent of political movements that endeavored to aid farmers in their economic... Read Article »

2017, Vol. 7 No. 2

In 2009, Brazil was in the path to become a superpower. Immune to the economic crises of 2008, the country's economy benefitted from the commodity boom, achieving a growth rate of 7.5 per cent in 2010, when Rousseff was elected. A few years later... Read Article »

2012, Vol. 2 No. 1

The research completed aimed to show that the idea of fair trade, using the example of goals for the chocolate industry of the Ivory Coast, can be described as an example of the economic ideal which Karl Marx imagined. By comparing specific topics... Read Article »

|