Featured Article:Reinterpreting the Treatment of the Rural Population by Peru's Shining Path

By

2017, Vol. 9 No. 02 | pg. 1/2 | »

IN THIS ARTICLE

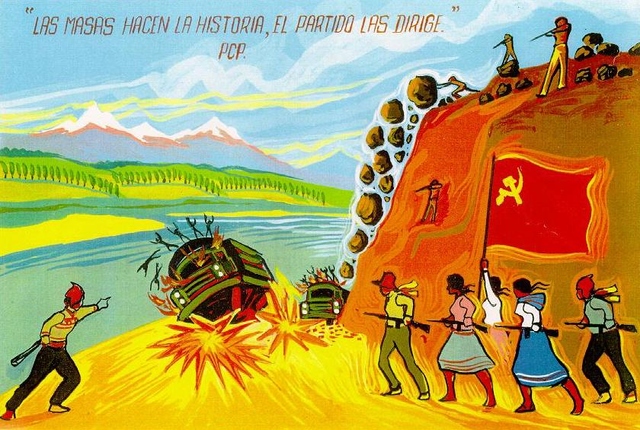

The Peruvian Communist Party (PCP) was founded as the Peruvian Socialist Party in 1928 by José Carlos Mariátegui after his analysis of the “semifeudal” Peruvian economic state, which did not strictly follow Marx’s socialist model.1 Just over 30 years later, the PCP began to radically transform under the teaching of Maoist thought by Abimael Guzmán, a philosophy professor at the National University of Haumanga and future leader of the party.2 Over the next two decades, the PCP renamed the Sendero Lumnioso (“Shining Path”) drew upon Mariátegui’s political and economic theories about Peru, specifically regarding the indigenous population, while implementing tactics outlined by Moaist thought. The result was paradoxical pro-indigenista and populist stances vocalized by the senederistas despite their violent acts against the Peruvian populace resulting in the deaths of nearly 70,000 people – many of whom were indigenous – since its launching of its “People’s War” in 1980.3 This investigation seeks to reconcile the originally pro-indigenista beliefs of Mariátegui’s PCP with the violent treatment of Peruvian indigenous peoples as part of the Sendero Luminoso’s insurgency against the government. Mariátegui and IndigenismoMariátegui asserted that socialist revolution in Peru would rely on the mobilization of its indigenous peoples based on their historic community structures and the economic and political systems which oppressed them as a legacy of colonization. Mariátegui understood the Incan empire of pre-Colombian Peru to be socialist, without having passed through the capitalistic mode of production as Marx would have predicted.4 The Spanish then imposed feudalism on this socialist Inca state, moving backward in Marx’s model of historical determinism. After gaining independence, Peru was, as Mariátegui wrote, a “semi-feudal state” in which the indigenous peoples were those most oppressed by capitalism, and hence those who would drive the inevitable socialist revolution of the country.5 The mechanism of this indigenous oppression was the gamonalismo system of land ownership which Mariátegui describes in his essay The Problem of the Indian; this essay outlines the institutional reasons that Peruvian governmental efforts to address indigenous oppression failed in the 1920s. The Problem of the Indian, along with his conceptualization of Incan communities, is evidence of Mariátegui’s attribution of economics to race and culture in Peru.6 A contributing factor to Mariátegui’s understanding of Peruvian indigenous peoples undoubtedly was the emergence of the indigenismo movement still present today, whose origins date back to the early 20th century. Because of the preservation of the ayllu, an indigenous community structure, the Indians of Peru maintained a systematic means of preserving their traditions, heritage, and culture.7 With this too came the development of a racial consciousness and identity which manifested themselves as the indigenismo movement. Because of the close association between race and economics which Mariátegui studied and verbalized, the rise of indigenismo could be understood to some extent as the construction of class consciousness – the prerequisite for socialist revolution.8 Hence, as Marisol de la Cadena affirms, “the leap from this step to an identification of the Indians as [economically oppressed] peasants would not long be coming.”9 The Connection between the Peruvian Peasantry and Indigenous PeoplesIt was exactly this link between the Peruvian peasantry and indigenous peoples, first facilitated by the gamonalismo observed by Mariátegui, which would later dictate the interactions between the Maoist Sendero Lumnioso and the Indians of Peru. Moreover, the same indigenismo that sparked Mariátegui’s application of Marxism allowed the land-ownership structure of gamonalismo to endure until Sendero militarized in 1980. The indigenismo paradigm, while necessary for the reclaiming of indigenous identity and national heritage, was a theme within cities’ political discourse and hence was an “urban and therefore external vision” of Peruvian Indians.10 This urban vision, physically distant from the indigenous peoples who commonly worked in the rural Peruvian highlands, allowed for the proliferation of a depiction of the Indian as a “victim of imperialism” and was compounded by the growing dependency theory “conceptualiz[ing] poor rural populations as simultaneously peasants and indigenous people.11” It was this confluence of political, economic, and social phenomena that created the framework in which the semi-feudal state of Peru could endure until the agrarian reforms beginning in 1969. The gamonalismo system, in which large landowners held economic leverage over the Indians working in their properties in the Peruvian highlands, “necessarily invalidate[d] any law or regulation for the protection of the Indian,” according to Mariátegui’s observations in 1928.12 This system too would allow the Peruvian Communist Party to shift its focus away from the indigenous identity of the Peruvian proletariat and later depict the class by its traits as the Peruvian peasantry within a span of 40 years. While this party under Mariátegui found the indigenous people of Peru to be the most oppressed group who would spark socialist revolution, the PCP by 1980 had shifted its focus to the peasantry as the most salient oppressed group of the country. However, the paradoxical guerilla tactics of the transformed Maoist Shining Path resulted in the murders of the indigenous peoples and peasants the party historically sought to help in its “Peasant War.” The Origin of the Sendero LuminosoThe transformation of the pro-peasant and pro-indigenous Peruvian Communist Party (PCP) into the terrorist Sendero can be traced back to the actions of a single political leader: Abimael Guzmán. He radicalized the party though his introduction of Maoism which would later serve as the basis for the Sendero’s declaration of the “People’s War” against the Peruvian government in 1980. When the international communist movement divided into pro-Beijing and pro-Moscow factions during the early 1960s, the PCP followed suit.13 Abimael Guzmán at this time was a prominent leader in the PCP-PR, the Maoist Patria Roja faction of the Peruvian Communist Party.14 It was not until the 1970s when Guzmán, a professor of philosophy, would transform the Universidad National San Cristóbal de Huamanga (UNSCH) in the highland town of Ayacucho into the epicenter of the Sendero Luminoso’s early activity.15 Ayacucho, whose name translates to “corner of the dead” from the indigenous Quecha language, was located in the Peruvian highlands and had a “primarily native Indian” population “exploited by the Caucasian urbanites under a pseudo-feudal system,” ever present in the nation’s economic history.16 This region was deeply imbibed in indigenous culture – evidenced in its name, population, and geography – and endured the perseverance of the gamonalismo system. Still resulting in the impoverished indigenous and peasant population, this economic structure motivated Guzmán to claim that Peru remained in the same condition of “semifeudalism” which inspired Mariátegui’s political writings of the 1920s. Guzmán witnessed the enduring problems which shaped Mariátegui’s politics and attempted to apply his own understanding of Maoism to solve these problems with new means five decades later. Until 1980, the Shining Path consolidated, studied, and created a five-point action plan defining their future course against the government. The early years of the Sendero Luminoso involved the reorganization of the party through strengthening ideological understanding. Members of Sendero “fervently” studied the works of Mariátegui from 1970 to 1972 at UNSCH, structuring the dogmatic basis of the party’s next phase of development later spurred by challenges to its influence in Ayacucho.17 Between 1973 and 1977, the growing prevalence of rival left parties and the “cosmopolitan outlook[s]” and desires held by UNSCH students and faculty were the driving forces which began to diminish Sendero’s initial, primarily intellectual presence in Peru.18 Thus, the Shining Path turned to Leninist ideas of a vanguard party to use the devoted students of Peruvian politics and Mariátegui’s writings to “reconstruct” the party, increasing its appeal and interaction with the same Peruvian peasantry at the focus of its intellectual analysis.19 By engaging with the peasantry directly, the Sendero concentrated its control over rural villages populated by appealing to the rural peasantry and indigenous peoples whose role in Peruvian society had been studied thoroughly by the party’s members. This also served as a tangible progression toward the Shining Path’s “five point plan of terror” after its declaration of the “People’s War” against the Peruvian government20,21. The party sought to “destroy the old foreign-dominated political system in Peru” via the conversion of “backward [economic] areas” into revolutionary bases, the destruction of bourgeois symbols, the use of guerilla tactics, the expansion of military bases, and the “total collapse of the state.22” It would do so by involving the peoples whom this state historically had most oppressed. This “People’s War” declared in 1980 originated at the intersection of the Sendero’s intellectual study of Lenin, Mao, and Mariátegui and the party’s interaction with the rural regions of the Peruvian population in order to amass support. Moreover, this developing relationship between the Shining Path and rural indigenous peasants is based in the historically conserved economic system of gamonalismo that should have ended in 1969 with non-effective agrarian reforms. The Sendero Luminoso’s formation began with the study of Mariátegui, whose The Problem of the Indian described this system as it existed in 1928. Because the party’s understanding of this economic system and its systematic means of limiting the political and social power of rural farmworkers, senderistas were naturally motivated to move outward toward the rural Peruvian farms. Alongside this mariateguismo, the party in the 1970s fixated on Maoist teachings which would ostensibly provide new applications to improving the economic conditions created in the wake of the recent reforms to gamonal land ownership. The Sendero’s Relationship with the Peruvian CountrysideThe tide of the revolutionary “People’s War” (guerra populista) beginning in the Peruvian countryside would them move toward urban centers. However, what began as mutual support and advocacy between the indigenous peasantry and the Shining Path would later unravel, resulting in massive abuses of power by the Sendero toward those it outwardly claimed to protect. Between 1980 and 1982, the Sendero focused on strengthening itself with the establishment of supply networks, amassing arms and militant power, and developing social connections to the primarily indigenous rural populations; it did this in order to directly oppose the Peruvian military. The Shining Path originally projected moralism in its practices which soon become progressively self-serving as the party moved toward a new phase of action in 1982. Upon its declaration of guerilla war in 1980, the Sendero relied on typical Maoist revolutionary practices; it sought to be self-reliant, only gaining arms and supplies from victims while maintaining a “pure” ideology.23 Such ideology also spawned ethical values promoted by the party in its “punish[ment] [of] adultery, alcoholism, vagrancy, robbery, and cattle rustling” in order to create the just, utopian society with classless solutions to problems ignored by the Peruvian state.24 It was during this phase of the party’s history that it gained the most readily given support from rural peasants. The politicizing of the countryside’s peasantry allowed for the formation of “support bases” far from urban centers and a supply of resources ranging from food to rural youth who would form militant guerilla legions for the sendero.25 This image of the Shining Path in the early period of its war appeared to seek ways of providing previously unmet economic needs of the peasant population and the social needs of the indigenous population.26 The Sendero was a new entity in the rural highlands, very different from the church, the state, or landowners whose methods directly oppressed the peasantry. Along with the propaganda by which the party depicted itself, this led many young peasants to be drawn to the party. However, older members of the rural, particularly “ethnically identified” communities were “most skeptical” of supporting the Sendero.27 Regardless, as the Shining Path began to use the supplies it drew from the countryside and the man power it gained from rural communities, it launched its actions against the state in guerilla fashion. When the Peruvian military began “indiscriminate[ly] repress[ing]” those it found in the rural highlands in response, the peasantry was given more reason to join forces with the Shining Path to protect their land.28 Yet, this period was short lived. Skepticism of the Shining Path proved to be well-founded as the organization began attempts to impose its will over “traditional communities” in order to consolidate power as a response to the governmental intervention.29 By the conclusion of 1982, the senderistas felt pressure from the Peruvian state in response to their guerilla tactics which included assassinations to governmental officials and damage to urban infrastructure, resulting in the declaration of an “emergency zone” in the city of Andahuaylas.30 While the Shining Path’s methods of warring against the state were supported by the rural peasantry, the organization quickly overstepped its graces with these communities. In order to gain control of the communities which had supported their efforts, senderistas were known to “impose [their] rule by demolishing the traditional community authorities.31” The Shining Path’s militants were ignorant of the institutionalized social contexts which gave traditional authorities their power in indigenous communities; and when the members of these communities witnessed the senderistas diminishing their cultural rites elevating their leaders into power, they responded with the tactics that the guerilla militants had taught them for years.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in History |