From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 10 NO. 1Quantifying China's Influence on the Shanghai Cooperation OrganizationQualitative AnalysisThe quantitative figures clearly suggest that SCO treaties are subject to a greater degree of influence from the PRC than ASEAN+1 documents are. However, similarities between China's National Defense White Papers and SCO treaties are even more dramatic when viewed side-by-side. The following three cases represent examples of near identical language in China's National Defense White Papers and SCO treaties.30 While it is reasonable to assume that there might be some parallels among these documents, these cases transcend mere similarity and, when viewed in conjunction with the above results, create a compelling argument that the SCO is an instrument of Chinese foreign policy rather than a wholly independent international organization composed of equals. Case One: Countering Western Influence in the RegionThe PRC has a clear interest in countering Western influence in East and Central Asia. Continued erosion of American power enables China to position itself as a regional hegemon within the larger Asia-Pacific region. Language within China's National Defense in 2000 and The Charter of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization includes clear condemnations of heavy-handed external influences, which are thinly-veiled references to the United States' quest to influence Asian domestic policies (for example, the United States' continued support of Taiwan.) Furthermore, the documents' prioritization of "mutual respect" indicates that both signatories claim to prioritize weaker states' rights to independently devise policies. Finally, both documents heavily prioritize cooperation among states. This reinforces previous conclusions that Chinese multilateralism in Central Asia is primarily devised to increase interaction and solidify bonds among included countries. China's National Defense in 2000China maintains that the multilateral security dialogue and cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region should be oriented toward and characterized by mutual respect instead of the strong bullying the weak, cooperation instead of confrontation, and seeking consensus instead of imposing one's own will on others.31 Charter of the Shanghai Cooperation OrganizationUnity and cooperation [is] realized through mutual respect and confidence by countries with different civilization backgrounds and traditional cultures… The SCO adheres to the principle of non-alignment, does not target any other country or region, and is open to the outside. It is ready to develop various forms of dialogue, exchanges and cooperation with other countries, international and regional organizations.32 When reading these two paragraphs in tandem, it is clear that the 2001 Charter of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization has heavily borrowed many of its objectives and theories from China's National Defense in 2000. Ideas of mutual respect (互尊, huzun), non-alignment, cooperation, consensus, and collective dialogue are readily present in both documents. In fact, it is fairly apparent that the two paragraphs seek to advance one consistent approach to multilateral engagement. This approach, at face value, prioritizes collective consensus building and incorporating the contributions of all involved parties. This inclusion is particularly notable, given that the findings of this analysis support the hypothesis that the SCO's policies and priorities are heavily influence by Chinese foreign policy initiatives. It is particularly fitting and rather ironic that China's claim to prioritize consensus-building, equal interaction among all states is replicated within the SCO's founding document.Case Two: Maintaining Regional Stability and Territorial SovereigntyChina's National Defense in 2006 and the SCO's Treaty on Long-term Good Neighborliness… show striking similarities when outlining states' commitment to maintaining territorial sovereignty. Even more notable, the below definition of territorial sovereignty and subsequent adherence to the CCP point-of-view that Taiwan is unequivocally a part of China, runs counter to the vast majority of non-Chinese depictions of the Taiwanese territorial dispute. In addition to the below depiction of territorial sovereignty leaving no room for Taiwanese independence, it also safeguards Chinese territorial control of Tibet and Xinjiang. China's National Defense in 2006The struggle to oppose and contain the separatist forces for "Taiwan independence" and their activities remains a hard one. By pursuing a radical policy for "Taiwan independence," the Taiwan authorities aim at creating "de jure Taiwan independence" through "constitutional reform, " thus still posing a grave threat to China's sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as to peace and stability across the Taiwan Straits and in the Asia-Pacific region as a whole. The United States has reiterated many times that it will adhere to the "one China" policy…But, it continues to sell advanced weapons to Taiwan, and has strengthened its military ties with Taiwan. A small number of countries have stirred up a racket about a "China threat," and intensified their preventive strategy against China and strove to hold its progress in check.33 Treaty on Long-Term Good Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation among member states of the Shanghai Cooperation OrganizationThe Contracting Parties, respecting principles of state sovereignty and territorial integrity, shall take measures to prevent on their territories any activity incompatible with these principles. The Contracting Parties shall not participate in alliances or organizations directed against other Contracting Parties and shall not support any actions hostile to other Contracting Parties. hostile to other Contracting Parties. The Contracting Parties shall respect the principle of inviolability of borders and make active efforts to build confidence in border regions in the military sphere, determined to make the borders with each other borders of eternal peace and friendship.34 The SCO's Treaty on Long-term Good Neighborliness… insistence that member states respect the "inviolability of borders" also carries interesting implications for Xinjiang—China's westernmost region. Xinjiang borders numerous SCO member states, and has long been plagued by the Uyghur ethnic group's separatist activity. That the SCO's Treaty on Long-term Good Neighborliness… binds signatories to oppose Uyghur, Taiwanese, and Tibetan separatism within their own borders represents a stunning commitment to PRC policies on the part of SCO member states. Furthermore, the recurrence of the key phrases: good neighbor (睦邻, mulin), peace (和平, heping), and separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi) are indicative of overarching policy similarities between official CCP and SCO policies. Case Three: Opposing Terrorism, Separatism, and ExtremismIn addition to containing similar language when describing states' obligation to counter Western influence within the region and the importance of safeguarding states' territorial sovereignty, official Chinese White Papers and foundational SCO documents contain similar language on combatting terrorism, separatism, and extremism. Grouping these three phrases together is a distinctly CCP creation. Referred to as "the three evils" (三股势力, sangu shili) within Chinese documents, using the phrases terrorism (恐怖主义, kongbu zhuyi), separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi), and extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi) in tandem allows the CCP to brand separatism in Xinjiang province as extremist Islamic terrorism that's closely connected to the resurgence in global terrorism seen post-9/11.35 Many pro-Uyghur human rights groups based in America and other Western nations find the connection between Uyghur separatism and Islamic extremist terrorism to be inauthentic and opportunistic.36 Shanghai Cooperation Organization Convention on Combatting Terrorism, Separatism, and ExtremismGuided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations concerning primarily the maintenance of international peace and security and the promotion of friendly relations and cooperation among States; aware of the fact that terrorism, separatism and extremism constitute a threat to international peace and security…recognizing that these phenomena seriously threaten territorial integrity and security of the Parties as well as their political, economic and social stability37 China's National Defense in 2002China opposes all forms of terrorism, separatism and extremism. Regarding maintenance of public order and social stability in accordance with the law as their important duty, the Chinese armed forces will strike hard at terrorist activities of any kind, crush infiltration and sabotaging activities by hostile forces, and crack down on all criminal activities that threaten public order, so as to promote social stability and harmony.38 The above paragraphs both acknowledge that threats derived from terrorism, separatism, and extremism harm member states' internal stability. While the notion that terrorism harms a states ability to preserve "political, economic, and social stability," is hardly controversial, the SCO's willingness to use all three phrases: terrorism (恐怖主义, kongbu zhuyi), separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi), and extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi), together is notable. In all ASEAN+1 documents, only the more internationally-accepted phrase, terrorism (恐怖主义, kongbu zhuyi), was included within the Joint Declaration of ASEAN and China on Cooperation in the Field of Non-Traditional Security Issues, which was also written in 2002. The SCO's utilization of separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi) and extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi) represents a tacit endorsement of PRC official policies connecting Uyghur separatism to the broader phenomenon of Islamic extremism. Furthermore, it demonstrates adherence to the CCP point-of-view, that one is not solely a "separatist," "terrorist," or "extremist"— but by definition, all three in tandem. ConclusionPresently, there is no comprehensive and universally accepted framework that enables observers to parse out the relative influence of state actors within multilateral organizations. Given that many of these organizations' dialogues and official meetings are closed to onlookers, researchers are primarily left with documents produced during meetings to ascertain the inner workings of multilateral organizations. Though difficult, discerning which state influences the policies and priorities of a multilateral organization can yield great benefits to those seeking to understand not only the organization's behavior, but also member states' approaches to participating in multilateral organizations. Given that China has only within the past few decades begun to meaningfully engage with multilateral organizations, and that the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is the first multilateral organization that the PRC has spearheaded, it is important to understand how China will approach its role as the leader of a multilateral organization. This analysis has used quantitative and qualitative approaches to demonstrate that contrary to claims of state equality within Chinese-led multilateral organizations, PRC policies are more heavily represented within official SCO treaties and documents than in other, comparable regional multilateral organizations. Quantitatively, a frequency analysis was conducted on the occurrence rates of ten key phrases within eleven selected documents. The eleven selected documents represented a sampling of ASEAN+1, SCO, and China's National Defense official treaties and White Papers. Additionally, all documents were originally written (or concurrently signed) in Mandarin. Evidence demonstrated that, while non-controversial terms such as peace (和平, heping) occurred at similar rates in all three document categories, terms that were more politically charged, such as separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi), and extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi), occurred at dramatically higher rates in SCO documents than in ASEAN+1 documents. Furthermore, phrases such as good neighbor (睦邻, mulin), and mutual respect (互尊, huzun), that require a higher degree of cooperation and engagement, appeared at drastically higher rates in SCO documents than in ASEAN+1 documents. Additionally, SCO documents were more likely to emphasize shared struggles (挑战, tiaozhan), and threats (威胁, weixie) than ASEAN+1 documents were. This indicates that SCO member states can more readily identify shared challenges to the stability of states within the organization. Holistically, quantitative evidence indicates that SCO documents have an unquestionably higher utilization rate of the ten identified key phrases. This, in turn, signals that the PRC has a greater ability to insert their policy initiatives into official SCO documents. Qualitatively, this analysis utilizes three case studies to provide in-text evidence of the overwhelming similarities between SCO documents and China's National Defense White Papers. Three relatively controversial topics were selected: countering Western influence in the region; maintaining regional stability and territorial integrity; and opposing terrorism, separatism, and extremism. Within each case study, an excerpt from China's National Defense advocating for a pointofview not commonly held within the international sphere, was excerpted and compared to a similar excerpt from an official SCO document. In all three cases, SCO documents unquestionably advocated for controversial positions, including: eschewing alignment with the United States, opposing self-determination for Taiwan, and branding political separatists in Xinjiang radical Islamic extremists. This qualitative support for the quantitative findings revealed in the first portion of the analysis underscore that the PRC is driving the policy initiatives of the SCO. The findings of this analysis have broad implications for future study of the SCO and Chinese behavior in multilateral organizations founded by the PRC. Presently, the SCO has not been conclusively shown to be primarily a tool of Chinese foreign policy. However, the evidence outlined above should give pause to those who hold the opinion that Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Russia have equal say in determining the SCO's policy objectives. The degree to which the SCO's treaties and declarations are binding should also be further considered. If the PRC has an outsized influence on the writing of treaties that require other member states to take certain courses of action, are they unduly coercing smaller, neighboring states? How does this affect the PRC's bid to establish itself as the unchallengeable regional hegemon? Given that India and Pakistan recently acceded to SCO as full member states in June 2016, this raises questions about whether or not the PRC will still be able to exert as much influence on SCO policy. If they are able to retain this level of influence, will India and Pakistan agree to take on relatively controversial positions? Furthermore, the SCO's joint submission of new standards for international cyber sovereignty to the United Nations should be further examined at a later date. Will the PRC continue to use the SCO as a platform to advocate for its preferred course of action within the larger international community? Given current regional dynamics within Southeast Asia, it is also important to note that the PRC was unable to exert substantive discursive influence on ASEAN+1 documents. Part of this is likely attributable to the fact that China was key broker of the SCO's creation and institutional framework while it is only an occasional participant in ASEAN's internal discussions. However, the fact that the PRC has designed the SCO to be an effective mouthpiece for Chinese positions is notable in and of itself. Onlookers concerned about potential Chinese efforts to replicate this effort within the Southeast Asian political landscape could review official ASEAN+1 treaties and agreements to identify tangible indicators of increased Sinification. More importantly, observers should pay close attention to any attempts to alter norms or operating procedures within ASEAN in a way that could preference PRC interests. Resolutions blocked by Cambodia and the Philippines should be heavily scrutinized by other member ASEAN states. If Chinese influence inhibits the organization from taking collective action to advance the majority of member states' interests, then ASEAN's overall effectiveness could significantly decrease, potentially harming member states' economic outlook and the rights of individuals living within member states. Outside of the SCO and ASEAN, the PRC has recently formed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). It remains to be seen whether or not the PRC will pursue a similar strategy within that multilateral organization, or if Chinese officials will allow for greater input from member states. Given the United Kingdom and Australia's membership in the AIIB, it is likely that China will not be able to pursue a strategy as aggressively anti-Western as seen in the SCO. However, to what extent other revisionist positions and methods are employed is yet to be determined. However, perhaps the most fascinating conclusion derived from this analysis is the PRC's readily visible hypocrisy in their categorization of the SCO as an organization comprised of equals. Perhaps the PRC's shift away from overtly pledging to adhere to the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence within issues of China's National Defense from 2010-present indicates that the it no longer intends to maintain a status equal to other, smaller participating states in multilateral organizations. Though the PRC claims that their form of "democratized international relations" allows for equal input from all actors, the analysis above has demonstrated that the SCO's policy agenda is driven by the PRC. When evaluating the future of Chinese multilateral engagement, it is important to distinguish between differing forms of Chinese multilateral engagement. The nature of their engagement should be evaluated based on which organization they are engaging with and what member states are represented within the group. Contrary to Chinese claims, the SCO's objectives are largely influenced by Chinese policy objectives. Evidence demonstrates that the PRC is able to leverage its influence on the SCO and ensure that sensitive issues are framed in line with CCP objectives. References"Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)." Nuclear Threat Initiative. October 21, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2016. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. 2010 Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Declaration on ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity. 2010. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN Community 2016 Fact Sheet. Jakarta, Indonesia. 2016. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Joint Declaration of ASEAN and China on Cooperation in the Field of Non-Traditional Security Issues. 2002. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Joint Statement of the China-ASEAN Commemorative Summit. 2006. Amnesty International. China: Gross Violations of Human Rights in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Publication. 018th ed. Vol. 17. London: Amnesty International, 1999, 10. Amnesty International. People's Republic of China China's Anti-Terrorism Legislation and Repression in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Publication. 010th ed. Vol. 17. London: Amnesty International, 2002. Ba, Alice D. "China and ASEAN: Renavigating Relations for a 21st-century Asia." Asian Survey 43, no. 4 (July/August 2003): 622-47. Baer, George W. One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994. "Beijing Inflicts a Defeat on Al-Qaeda." South China Morning Post, January 25, 2007. Campbell, Caitlin, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. "Highlights from China's New Defense White Paper, ‘China's Military Strategy.'" Washington, DC. 2015. "Chinese FM Calls for United Front to Fight Terrorism." Xinhua. November 15, 2015. Accessed February 06, 2016. Chung, Chien-Peng. "The Shanghai Co-operation Organization: China's Changing Influence in Central Asia." The China Quarterly, 2004, 989-1009. FIDH—International Federation for Human Rights, Antonie Bernand, Michelle Kissenkoetter, David Knaute, and Vanessa Rizk, The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Vehicle for Human Rights Violations. Paris, France, August 2012). Gill, Bates. "China's New Security Multilateralism and Its Implications for the Asia–Pacific Region." In SIPRI Yearbook 2004, 210. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2004. Katsumata, Hiro. ASEAN's Cooperative Security Enterprise: Norms and Interests in the ASEAN Regional Forum. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009). Kent, Ann. "China's International Socialization: The Role of International Organizations." Global Governance 8, no. 3 (2002): 343-64. Rozman, Gilbert. "Invocations of Chinese Traditions in International Relations." Journal of Chinese Political Science, 17, no. 1, (2012): 111-24. Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001. "Shanghai Cooperation Organization Official: Terrorism in Xinjiang Is a Close Variant of International Terrorism." Xinhua. June 09, 2014. Accessed March 2, 2016. Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai Convention on Combatting Terrorism, Separatism, and Extremism. June 15, 2002. Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Statement and Plan of Action by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Member States and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on combating terrorism, illicit drug trafficking and organized crime. 2009. Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Treaty on Long-Term Good Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation Between the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 2007. Shanghai Five. Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions. Shanghai, China. 1996. Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2000, Beijing, China. 2000. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2002, Beijing, China. 2002. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2006, Beijing, China. 2006. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2008, Beijing, China. 2008. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2010, Beijing, China. 2010. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2015, Beijing, China. 2015. The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. China's Position Paper on the New Security Concept, Beijing, China. 2002. Wu, Guoguang, and Helen Lansdowne. "International Multilateralism with Chinese Characteristics: Attitude Changes, Policy Imperatives, and Regional Impacts." In China Turns to Multilateralism: Foreign Policy and Regional Security, 3-18. New York, NY: Routledge, 2008. Wuthnow, Joel, Xin Li, and Lingling Qi. "Diverse Multilateralism: Four Strategies in China's Multilateral Diplomacy." Journal of Chinese Political Science 17, no. 3 (July 20, 2012): 269-90. Zhao, Huasheng. "China's View of and Expectations from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization." Asian Survey 53, no. 3 (2013): 436-60. Zhang, Yunling. "One Belt, One Road: A Chinese View." Global Asia 10, no. 3 (October/November 2015): 8-12. Endnotes

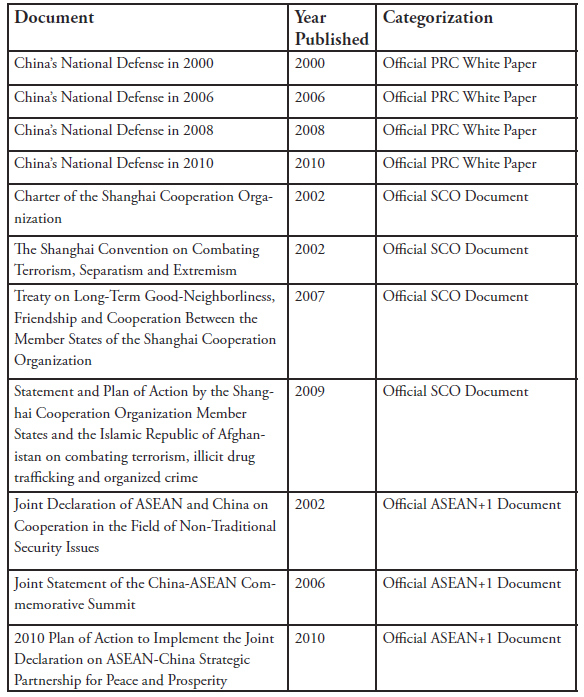

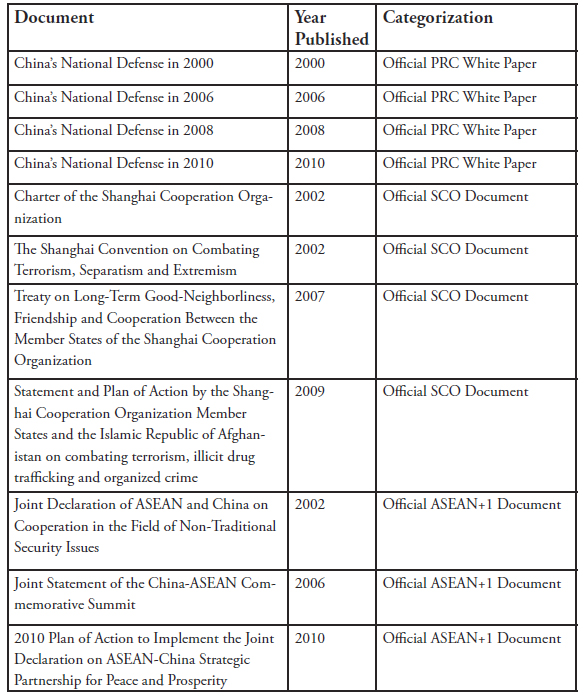

Appendix 1: Document CategorizationSuggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |