The Many Faces of Odysseus in Classical Literature

By

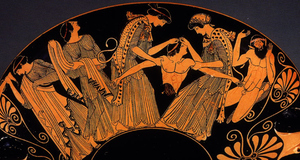

2015, Vol. 7 No. 03 | pg. 1/2 | » AbstractThe defining characteristics of Odysseus in classical literature are interpreted in wildly different ways by different authors: he is portrayed as a hero in Homer’s The Odyssey, a villain in Sophocles’ Philoctetes, a self-serving opportunist in Sophocles’ Ajax, a deceitful figure in Virgil’s Aeneid, and a scoundrel in Euripides’ Hecuba. Each of these different interpretations draws on different features of Odysseus’s character and taken together they reveal the complexity and versatility of this classic protagonist. Throughout classical literature, the different depictions of Odysseus range widely: he is variably portrayed as a hero in Homer’s The Odyssey, a villain in Sophocles’ Philoctetes, a self-serving opportunist in Sophocles’ Ajax, a deceitful figure in Virgil’s Aeneid, and a scoundrel in Euripedes’ Hecuba. In The Odyssey, though stubborn and boastful, Odysseus otherwise exhibits courage, cunning, sharp intellect and concern for his men -– all traits that characterize the archetypal hero. In Philoctetes, Odysseus is deceitful and conniving, as he abandons morality by devising a plan to exploit a sick, wounded, and forgotten man (Philoctetes). In Ajax, Odysseus appears to act nobly and magnanimously when he advocates a proper funeral for Ajax; however, upon closer scrutiny, one can allege that this man is, rather, primarily serving his self-interests. In the Aeneid, Odysseus is depicted as crafty by virtue of the scheme that he devised to sack Troy. In Hecuba, Euripedes portrays Odysseus as heartless and egocentric owing to his indifference to human suffering. In The Odyssey, Homer illustrates that, despite all of his human frailties, he is ultimately a heroic character due to his bravery and sharp intellect. Furthermore, Odysseus shows himself to be a cerebral, cognitive character when he overcomes any lustful or manly urges to leave Calypso; he lets rational thought prevail in eventually extricating himself from her lair. He also acts in a clever fashion when he describes himself as homesick to Calypso: “Mighty goddess, do not be angry with me over this. I myself know very well Penelope, although intelligent, is not your match to look at, not in stature or in beauty…You’ll never die or age. But still I wish, each and every day to get back home, to see the day when I return” (Homer 5.267-275). Rather than overtly stating that he misses his wife, Odysseus shrewdly provides another excuse that will not evoke jealousy in Calypso but, rather, a desire to help him. His cunning plan to conceal the truth allows him to obtain assistance from Calypso and, therefore, satisfies his self-serving interests. His quick wit continues to manifest itself when he offers the Cyclops, Polyphemus, some wine so as to inebriate the creature: “Cyclops, take this wine and drink it, now you've had your meal of human flesh, so you may know the kind of wine we had on board our ship, a gift of drink I was carrying for you, in hope you'd pity me and send me off on my journey home” (Homer 9.458-464). In so doing, he facilitates his crew’s escape from the island, as the wine lulls Polyphemus into a deep slumber. Thus, this act of sheer cunning depicts Odysseus as a shrewd character who actively outthinks his opponents in whatever challenge with which he is encumbered. By the same token, Odysseus demonstrates his quick wit when he tricks the Cyclops in order to cover his tracks: “Cyclops, you asked about my famous name. I'll tell you. Then you can offer me a gift, as your guest. My name is Nobody. My father and mother, all my other friends— they call me Nobody” (Homer 9.484-488). By employing such convincing rhetoric, Odysseus eventually escapes the land of the Cyclops, overcoming yet another obstacle due to his acumen. Homer clearly portrays Odysseus as an astute and heroic figure, accordingly. Though unabashedly obstinate,poignantly demonstrated when he insists upon listening to the Sirens (Homer 12.249-251), Odysseus can also be branded an incisive character, especially when, upon revealing his true identity to his son, Telemachus, he imparts instructions for his cleverly devised plan to kill the lustful suitors: “Take all the weapons of war…and put them in a secret place, all of them, in the lofty storage room…But leave behind a pair of swords…for the two of us to grab up when we make a rush at them” (Homer 16.354-372). Odysseus’ strategic idea to deprive the suitors of their weapons so as to render them utterly helpless demonstrates his intellectual prowess. His ability to quickly conjure up and set into motion a cunning plan serves as a testament to his lively and heroic persona. Odysseus is decisive and has the courage to act upon his convictions; however,his lack of hesitation is prudently tempered by an appropriate amount of patience, ultimately culminating in impeccable timing, with him definitively striking at just the right moment. Through his efforts to confront and kill the suitors, Odysseus displays courage and concern for his family. Moreover, Odysseus possesses abundant physical attributes, including strength, power, dexterity and skill with fighting tools– all of which complement his mental prowess, resourcefulness and ingenuity, thus qualifying him as a quintessential heroic figure. In Philoctetes, diametrical to the Homeric portrayal, Sophocles reveals an Odysseus whose thirst for glory transcends his moral scruples, thus depicting him as a villainous figure and antagonist. Odysseus convinces Neoptolemus, Achilles' son,that they must employ fraud in order to win the titles of “virtuous” and “wise” (Sophocles, Philoctetes 119). Odysseus proposes that they beguile Philoctetes into returning with his arrows to Troy because they alone are prophesized to bring good fortune with a speedy victory in the war against Troy. The two men express their distinct views on the principle of moral integrity: Odysseus: ‘I know, my boy, I know that this sort of thing is not in your character. You don’t like uttering such lying language nor do you like plotting against people but you must also know what a delight it is to gain a victory after a struggle.’ Neoptolemos: ‘Distressing words make for distressing deeds, Odysseus, son of Laertius and it is not in my nature, nor was it in my father’s nature to do treacherous things.’ (Sophocles, Philoctetes 79-94) Odysseus’ insistence upon lying for the sake of obtaining personal benefit in the form of victory is appalling. Odysseus appears utterly devoid of compassion or concern for others, as he equates treacherous scheming and doing harm unto others with a favorable reward and achieving success. This lack of sensitivity manifests itself in this passage and contributes to the depravity that characterizes Odysseus throughout this play. Neoptolemus’ response highlights his moral rectitude and resolve to remain honest while also indirectly amplifying Odysseus’ mendacity through juxtaposition. As the play progresses, he continues to coerce and corrupt Neoptolemus into abandoning his moral principles through manipulation and persuasive rhetoric. Odysseus condones prevarication if the truth serves a redeeming purpose, particularly when he remarks, “When a deed brings some benefit one must not waste any time committing it” (Sophocles, Philoctetes 108-111). Odysseus is deftly portrayed as being self-serving and greedy, as he belabors the importance of telling a lie for the sake of self-aggrandizement and ingratiating himself with the gods and his fellow men. For this unsavory incarnation of Odysseus, the ends do justify the means: he uses self-interest and the garnering of personal benefit as justification for lying, thus highlighting his manipulative and conniving nature wherein he is willing to abandon morals in order to make Neoptolemus acquiesce to his proposition. He continues to break Neoptolemus down, peeling back his layers one by one until the latter is stripped of his moral principles and ultimately relegated to compliance. The aforementioned passage suggests that Odysseus is an archetypal villain who is firmly rooted in his deprave ways: he exploits Neoptolemus and assigns him the dirty work of acting under a pretense in order to gain Philoctetes’ trust, all while not seeming to show any remorse for his actions. Furthermore, this blatant exploitation portrays Odysseus as an adept manipulator and avaricious opportunist willing to employ whatever means necessary to survive and ultimately achieve his goal: his vicious conniving tactics are second to none. Odysseus’ desire for glory and respect from his fellow countrymen propel him to adapt to the circumstances by employing deceit and abandoning the virtue of honesty. Thus, one can intimate that Odysseus serves as a dramatic foil to the honorable and self-righteous Philoctetes. In addition, though portrayed in a negative fashion, he is also represented as an adaptable man like Theramenes, an Athenian politician of Ancient Greece.In Philoctetes, his manipulation of Neoptolemus through persuasive rhetoric further promotes a negative connotation of Odysseus in classical literature. In stark contrast, in Ajax, also by Sophocles, Odysseus can be deemed noble and magnanimous, prima facie, by virtue of his vehement support of a burial for Ajax. In defiance of the Atreidae, Odysseus eloquently counters Agamemnon’s desire to leave Ajax unburied: “In deference to the godsdon’t be so unyielding you throw Ajax out without a burial…for all the man’s hostility to me,I would not disgrace him…if you dishonor him, you would be unjust. It would not harm him,but you’d be contravening all those laws the gods established” (Sophocles, Ajax 1620-36). The fact that Odysseus argues so emphatically for his enemy’s burial further underscores his magnanimity. However, underneath the surface, one might suggest that this seemingly noble act was performed only in order to ultimately curry favor with his countrymen and the gods. Odysseus constantly alludes to the gods and insists that Ajax must be buried in order to appear just and obedient to these capricious beings. For instance, when accused of appearing cowardly, Odysseus remarks, “No. Every Greek will think we’re being just” (Sophocles, Ajax 1671). This statement arguably divulges Odysseus’ true intentions, as his ostensibly disingenuous actions reek of underlying, self-serving motives – Ajax would be rolling over in his grave.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |