A Contemporary Analysis of Action Films with Female Leads

By

2016, Vol. 8 No. 09 | pg. 1/2 | »

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

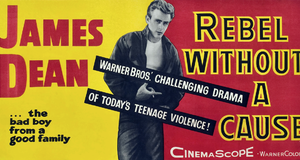

A doorbell rings. Off screen, we hear a sing-songy “Coming!” A woman dressed in a cerulean track suit rushes to the door, expecting to find her daughter home from school. Instead, she finds another woman, blonde and leather jacket-clad. With one startling punch, the blonde woman simultaneously initiates a fight and inserts herself into the home. The two women proceed to destroy the living room of the house: shoving each other into framed pictures, propelling into tables, throwing shelves of painted china, becoming more and more bloodied by the second. The fight reaches a standstill at the window, through which we see the homemaker’s daughter dropped off by the bus. The only sound comes from the broken glass beneath their feet. Such fight sequences are a hallmark of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill films, but something usually glazed over in filmic discourse is the way in which the female characters interact with their surroundings. While women in film have been traditionally allocated to domestic spaces, whether to clean, cook, or care for children, new cinematic examples (such as Kill Bill) have cropped up in which women dispassionately destroy the spaces that had once been so restrictive. The Bride, as played by Uma Thurman in Kill Bill Volumes 1 and 2, often relishes in the ability to destroy domestic spaces, all the while maintaining her own lack of a home. Such destruction may be one way that these films subvert the ever-pervasive male gaze, or at least call attention to it. Kill Bill of course does not offer the only instance of subversion, and interaction with space is not the only method, but it serves as a case example. Destruction of space, an action that falls under the cinematic category of blocking, may be one way we can interpret the mise en scène of a film as redirecting our own gaze. For the purposes of this article, we may refer to this as scene regard, or loosely, “scene gaze.”It would be ludicrous to say that contemporary film has completely abolished the male gaze. To claim, however, that contemporary film is still completely intertwined with it would be similarly futile. It seems as though contemporary film falls somewhere between the two. With the exception of some anachronistic outliers, film has made great strides as far as the portrayal of women is concerned. Forty years ago, when British film theorist Laura Mulvey wrote “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), action films featuring female leads were practically unheard of. In fact, films with women in lead roles were extremely rare, save for the melodramatic mode, a genre exclusively geared towards women about women—and irritatingly nicknamed “women’s weepies.” With the shift into the new millennium, however, films began to gradually incorporate female leads—and in a multitude of genres. Not only have these films offered radical new representations of women, they have also been enormously popular. In 2003, Kill Bill Vol. 1 was released, bringing in over twenty-two million dollars on opening weekend and winning over twenty awards. The following year, Vol. 2 was released, earning over twenty-five million in box office revenue. In 2015, Mad Max: Fury Road, a film more focused on Charlize Theron’s character, Imperator Furiosa than Max himself, practically shattered the box office. It made over forty-four million dollars on opening weekend and won over two hundred awards. These statistics may seem frivolous, but they serve a very specific purpose: to show that people enjoy films with strong and physically powerful female protagonists. But to what extent do these leading ladies hold acclaim solely for their performance (as opposed to their appearance)? How often are women in film still sexualized? And how many of these film goers remain passive participants in the male gaze? These questions are tricky, as such films provide evidence of the male gaze both at work and under criticism. Perhaps a more constructive question may be: has a new filmic gaze emerged in contemporary cinema that is facilitated heavily by mise en scène? One that may be tongue in cheek, but critical, nonetheless? I intend to answer this question, and not just through the lens of contemporary Hollywood. This study offers close analyses of Kill Bill Vol. 1 and Mad Max: Fury Road from Hollywood and Sympathy for Lady Vengeance and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo from Global Art Cinema. Here I intend to determine the parameters of a contemporary filmic gaze, one that is, I seek to show, governed by mise en scène. Bridging feminist film theory and psychoanalysis, Mulvey’s 1975 essay was groundbreaking, if not alone for its contribution to filmic discourse the idea of the male gaze. Briefly put, Mulvey asserted that in classical Hollywood narrative cinema, the look of the filmgoer is more often than not directed and controlled by that of the male protagonist. The male gaze is problematic because it assumes that the body in the cinema is always a heterosexual male—which is hardly the case. Although Mulvey wrote about films that were released over sixty years ago, the notion of the male gaze continues to proliferate in all areas of contemporary media. Mulvey applied the male gaze to film alone, but today the male gaze can be examined in many forms of media—whether it be the Pamela Anderson PETA ad, Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines music video, even certain news shows. Indubitably, the male gaze and its implications have not been abolished on the whole, but it may be useful to determine how far contemporary film has come. Since Mulvey studied films directed by males and starring females, I chose to follow the same thought process. Where our analyses diverge, however, is in our methodologies. Mulvey analyzed her films through a psychoanalytic lens and cinematography, while I have chosen the less-looked-through lens of mise en scène. Further, where Mulvey offered no concrete solution to the male gaze, my analysis proposes direct lines of flight. There has since been at least one other analysis of gaze via mise en scène, albeit from a very different perspective. In 2013, Stella Bruzzi published Men’s Cinema: Masculinity and Mise en Scène in Hollywood. In this book, Bruzzi delineates the ways in which Hollywood is largely a men’s cinema, and how a masculine aesthetic is conveyed through mise en scène. Her choice, however, to focus on male-dominated action films (Mission Impossible, Point Break), and a number of classical Hollywood films (There’s Always Tomorrow, Written on the Wind), provides for a rather exclusive study. My choice to focus on female-led action films in contemporary cinema may be exclusive in its own right, but it may provide an interesting counterpoint to Mulvey and Bruzzi, two thinkers who believe the film industry to be overwhelmingly hegemonic. Although there are many differences between Kill Bill, Mad Max: Fury Road, Lady Vengeance, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, one common trope links all four: the aggressive killer-lady. This female figure is an atypical protagonist, as she both drives the narrative action and instigates the violence. The female leads of these four films serve as the axis on which this entire study rotates. Through analyses of the scene regard—that is, the mise en scène gaze— coupled with a focus on the female leads of four contemporary action films, I intend to produce an argument that serves as a counterpoint—or perhaps an updated counterpart—to Mulvey’s monumental essay. Although the examination of these films via mise en scène is slightly more specific than a general analysis, it remains dubiously broad. After dissecting mise en scène into the following categories, I can produce a lens with which to analyze the films: (1) Place; (2) Blocking; (3) Costuming; (4) Props. Under the first category, place, attention will not only be paid to the variety of places (prisons, domestic spaces), but also the different non-places that exist in the diegeses of these films. The non-place, coined by contemporary French anthropologist Marc Augé, refers to a transient place that “cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity” (77-78). According to Augé, these non-places are the result of supermodernity, and can range anywhere from subway platforms to hospitals. It may be useful to consider the role non-places plays in the lives of these women. It is almost as if these women spend more time in non-places, a stark contrast from the heteronormative domestic spaces of their classical Hollywood predecessors. The second category, blocking, pertains to the ways in which the female protagonists interact with both their surroundings and with others. These women often take part in the destruction of space. Also, they often are instigators of violence. But what propels them to commit these dangerous acts? Are they driven by revenge? Desire? Illness? It may also be useful to consider the role sexual violence plays in the films—as the victimization of women is often a glazed over feature of prominent “body genre” films. One important aspect of character is performative presentation—that is, their costume and makeup. These four films present a broad spectrum of clothing styles, with Lee Geum-ja of Lady Vengeance on the overtly feminine end, Beatrix Kiddo of Kill Bill in the middle, and Imperator Furiosa of Mad Max and Lisbeth of Dragon Tattoo on the end of hardcore androgyny. It is imperative to include costuming as the third category of this analysis because more often than not, women in film are defined by what they wear (e.g. Wonder Woman, Dorothy Gale, Elle Woods). Women are so frequently sexualized in film vis-à-vis their style of dress that it is almost inevitable to consider the role costuming plays in our perception of these women. Although type of space is important to consider, it should not be the only aspect of setting taken into account. The appearance of these spaces is just as important: it leads us to consider the objects within the space— or the props. Props are integral to the study of setting in these films, for they are what give the diegetic space verisimilitude, or the illusion of reality. In “Visual Pleasure,” Mulvey, drawing from Freud, suggests that male protagonists turn their female counterparts into fetish objects. This facet of the argument is crucial for it lumps women into a category with the inert; it proclaims that they are only objects to be looked at, used, and disposed of. Not only do Kill Bill, Mad Max: Fury Road, Lady Vengeance, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo transform women from object to subject, but they turn the objectifying male gaze toward objects—creating new fetishes. All too often, action films with male leads objectify and sexualize women. In these films, however, it is the objects that are analytically edited and fetishized. A clear example from Kill Bill is the unequivocal allure of the Hattori Hanzo swords. Though the reasoning for this fetishization of props may be unclear—be it intentional subversion of the male gaze or merely an unnatural obsession with violence— its implications are important when considering the portrayal of women in contemporary cinema. No Non-Place Like HomeSave for Bill’s pseudo-monologue and the almost unintelligible insults exchanged during the frenetic Beatrix/Vernita Green duel, the first real conversation in Kill Bill is about a place. At the tail end of the fight, while Vernita and Beatrix are at a standstill in front of the window, Vernita’s daughter, Nikki, comes home from school. Nikki walks through the door and pauses, slowly processing the scene in front of her: a TV room in disarray, a sweating stranger, a bloodied mother hiding something behind her back. The following conversation ensues:

The destruction of the domestic space serves as an elephant in the room—yet it cannot not be talked about. Vernita’s refusal to admit to her daughter the violent acts that had just occurred (and by implication her violent past as an assassin), attaches feelings of embarrassment and shame to the situation. Therefore, this dialogue between Vernita and Nikki serves as a basis on which to treat different spaces and violent acts throughout the film. In other words, in destroying the domestic space, Beatrix not only destroys a rooted, meaningful place (something I will explore further), she also destroys the guilty center, and opens the floor for a discourse about the way these types of spaces really function in film in general. All four of these films host a multitude of settings. There is the house of Vernita Green and the House of Blue Leaves (a multi-functional Japanese Bar and the headquarters of O-Ren Ishii) in Kill Bill, the post-apocalyptic Australia desert and the “War Rig,” an oil rig that belongs to Imperator Furiosa (of Mad Max), and the generically postmodern western Australia where Geum-ja (of Lady Vengeance) travels to visit her estranged daughter—to name a few. There are so many different settings in these films, but rather than ponder where they are, it may be more useful to consider the functions that they serve—that is, if they are places or non-places. In the mid-nineties, French anthropologist Marc Augé wrote Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. In this book, he introduces a fresh interpretation of non-place, as a transient space without enough significance to be considered a legitimate place. He argues, “Place and non-place are rather like opposed polarities: the first is never completely erased, the second never totally completed” (79). While a bit nebulous at times, Augé does very meticulously describe exactly what non-place is. To him, a non-place is a space of either transport, transit, commerce, and leisure, with the traveler’s space as the archetypal non-place. Later, he writes, “A world thus surrendered to solitary individuality, to the fleeting, the temporary and ephemeral, offers the anthropologist (and others) a new object, whose unprecedented dimensions might usefully be measured before we start wondering to what sort of gaze it may be amenable” (Augé 79). This excerpt is key, for not only does it speak to the reclusive tendencies of human beings and the ways in which they interact—or do not interact— within these non-places, it brings into consideration the gaze itself, holding it as an authority, suggesting that all these things fall compliant to it. Using Augé’s criteria of non-place as a space of transport, transit, commerce, or leisure, I assembled a list of the various places and non-places the four female aggressors inhabit. I found that there were sixteen places, among them five houses, a hospital, an office building, and three apartments; and thirty non-places, including a truck (transport), two airports (transit), two resorts (leisure), and a hair salon (commerce). Evidently, there are almost double the amount of non-places than places in these films—but how is this significant in terms of the male gaze? In “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Mulvey suggests, “However self-conscious and ironic Hollywood manages to be, it always restricted itself to a formal mise-en-scène reflecting the dominant ideological concept of the cinema” (7). That is to say, classical Hollywood has fallen victim to an unremitting position reliant on heteronormative gender roles. In closing, she proclaims that the only solution to this hegemonic system is a radical shift in film form, or an alternative cinema that is both politically and aesthetically avant-garde. Kill Bill, Mad Max: Fury Road, Lady Vengeance, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo are by no means avant-garde, yet they still somehow manage to nullify many of these dominant ideologies (namely, the ones that restrict women to domestic positions). For the women of the films Mulvey analyzes, possible story arcs range from evolving into a full-blown fetish object (à la Von Sternberg), surrendering to a man via marriage (like in Hawk’s To Have and Have Not), or total annihilation through death (as in Hitchcock’s Vertigo)—not a very promising range of fates. In a refreshing twist, Beatrix, Furiosa, Geum-ja, and Lisbeth all make it out of these films both alive and (contentedly) alone. Since these women mostly function in non-places (as opposed to domestic spaces),they finally have the opportunity to redefine themselves in the cinematic world; they can finally pioneer new identities separate from those prescribed by classical Hollywood. Ultimately, the way these four women navigate non-places and claim them as their own lays the foundation on which they can subvert the male gaze of their own accord. This foundation is only enhanced by the way the women move within these spaces. Anything But a Victim

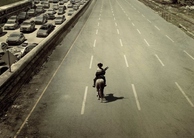

This scene between Max (Character A) and Furiosa (Character B) is one of the first fight scenes of Mad Max: Fury Road, and a useful example for mapping the blocking of these films. Blocking is an important aspect of this study’s formulation of scene regard, and although it is nearly impossible to analyze every movement of these female figures, we can at least consider the most powerful movements of the films—the fights. Fight sequences in these films are no different from what we would expect to see in most other action films. One major difference, however, is that not only are women doing most of the fighting, but they also usually emerge victorious. Gender is almost entirely eclipsed by the spectacle of (non-gendered) violence in these films, allowing women to easily adapt roles typically occupied by men. In “Mindful Violence: The Visibility of Power and Inner Life in Kill Bill,” (2004) Aaron Andersen, a prominent Hollywood fight director, underscores this. Although the article focuses mostly on specific fights in Kill Bill, Andersen’s articulation of the action genre as a whole is significant: Many action films use violence as a central metaphor. To be sure, a large part of the appeal of these films is the visceral spectacle of that violence. Yet, what is not often noted in studies of action films is that one of the most common genre themes presents an inner journey resulting in some sort of fundamental character transformation (2). Perhaps instead of dwelling on the fetishization of violence in film in general and the problems that may arise from it, we can consider the ways in which violence may encourage egalitarian attitudes. That is to say, showing fights between men and women that are authentic rather than rooted in spectacle may encourage spectators to consider men and women as equal. The Character A–Character B scene in Mad Max: Fury Road corroborates this egalitarian notion. By looking at Max and Furiosa as genderless characters (A and B), we can think about how ineffectual gender really is. The clothes Max and Furiosa wear are curiously similar, which visually neutralizes their genders. Additionally, the two fight in a way that suggests a uniformity in physical ability. Neither Max nor Furiosa has control over the other for more than a few seconds. Even spatially, they are almost always at the same level. The fight eventually ends with neither of them victorious—and nobody is seriously injured. At no point in this sequence do we question the plausibility of such a fight, which speaks to the notion that it is possible to show men and women as equal sans audience backlash. It may be useful to think of violence as, according to Andersen, a form of empowerment. He writes, “I suggest that the main reason violence becomes so important to telling these types of inner journeys on film is that acts of violence make the idea of personal power itself visible” (3). In other words, instead of viewing cinematic violence as gimmicky, we can think of it as a palpable display of power, and even a platform for the negotiation of gender politics. Indeed, it may even be useful to consider these fight sequences as working in tandem with the costumes to foster a “degendering” of the women protagonists. Not only do the fight sequences display women’s empowerment, they also work to blur the harsh line of the gender binary. That is not to say these films perform a complete erasure of femininity, but rather, in the fight sequences, we may temporarily forget their gender entirely. Later on in his article, Andersen avers that in action films there is a tendency to resort to physical violence more often than necessary as a means to evoke audience reaction. He proclaims, “For critics, it might therefore be tempting to evaluate scenes of physical violence only in terms of this visceral response (and in fact many film critics deride action films as nothing more than part of a low-culture ‘body’ genre for exactly this reason)” (6). This statement implies that action films may be traditionally lumped into the low-brow category of the body genre. In my reading, however, the action films with female leads, though fraught with excessive violence, do not sadistically position women at the level of the other body genres. Andersen’s evocation of body genre may be in reference to Linda Williams’s famous article “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess” (1991), which focuses on melodrama, pornography, and horror as genres linked by their implementation of bodily excess. Williams offers her own interpretation of Carol Clover’s notion of the body genre, writing of its pertinent features: “First, there is the spectacle of a body caught in the grip of intense sensation or emotion. Carol Clover, speaking primarily of horror films and pornography, has called films which privilege the sensational ‘body’ genres (Clover 189). I am expanding Clover’s notion of low body genres to include the sensation of overwhelming pathos in the ‘weepie’” (4). To put it simply, Clover coined the notion of “body genre” to encompass the genres of horror and pornography. To follow, Williams expanded the definition to include the melodramatic mode. Finally, Andersen proposes the addition of action film as a body genre as well. Williams characterizes the body genre through sensational excess, suggesting that the sensations of the films are meant to induce visceral responses from the spectator. The reason for this, Williams suggests, may be a lack of distance. She posits, “What seems to bracket these particular genres from others is an apparent lack of proper esthetic distance, a sense of over-involvement in sensation and emotion” (Williams 5). This absence of critical distance for the (often woman) spectator is how many feminist film theorists such as Laura Mulvey and Mary Ann Doane explain the male gaze’s tenacious grip on the film industry. We can argue, however, that the four films considered here do not bombard the spectator with bodily excess; instead, they bombard with a style of violence, which lacks the type of sensational and emotional over-involvement described by Williams. In other words, these films evade a form of pathos that once entangled women spectators in the diegesis, thus allowing critical distance from the film world and subversion of the male gaze. Williams later writes, “Each of the three body genres [porn, horror, and melodrama] I have isolated hinges on the spectacle of a ‘sexually saturated’ female body, and each offers what many feminist critics would agree to be spectacles of feminine victimization” (6). In these four films, there is sex, but not the kind of sex that fits the bill of “sexual saturation;” that is, we see sex happening, but it is in no way meant to pique spectatorial arousal. For instance, in a particularly puzzling scene in Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, an affectless Lisbeth visits Mikael in his room, has sex with him, then leaves. No words are exchanged between the two. This detachment of emotion from the sexual act coupled with the lack of ecstasy in Lisbeth’s face works not only to desensitize sex itself, but to also distance the spectator from the world of the film. These women are not interested in the “prize” of sex à la James Bond, but rather, their satisfaction comes from the sheer fact that they are on a platform equal to men, that they are able to win physical challenges, and that they are, in a sense, liberated. While there is a notable amount of feminine victimization in the films, it is never taken to the point of spectacle. Instead, the sexually assaulted women turn their situations around and defeat their victimizers as a form of empowerment. For example, in Kill Bill, it is implied that Beatrix’s nurse, Buck, was not only having sex with her comatose body, but offering it up to anyone willing to pay for access. In Mad Max: Fury Road, there is also the implication of rape, as the sickly leader Immortan Joe has a harem of beautiful women at his disposal, whose sole purpose is to satisfy his desires and carry his children. In Lady Vengeance, while Geum-ja is in prison, there is a woman nicknamed “The Witch.” At one point, The Witch forces another inmate to perform oral sex on her in the pool. Finally, in Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Lisbeth’s legally guardian violently rapes her. While sexual violence is a delicate subject matter, and not the most comfortable thing to watch on screen, there is a major difference between how it is handled in these films versus in the body genres. While pornography and horror films often victimize women, leaving them powerless and— more often than not— tortured and traumatized, Kill Bill, Mad Max, Lady Vengeance, and Girl with the Dragon Tattoo turn the sexual violence on its head, returning the power to the victimized women. In Kill Bill, Beatrix kills Buck and a prospective customer. In Mad Max, Immortan Joe meets a “satisfying” end at the hands of Furiosa. In Lady Vengeance, Geum-ja slowly poisons “The Witch” with bleach. Finally, in Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Lisbeth not only restrains and sexually assaults her abusive guardian in turn, but uses secret footage of him raping her as leverage to keep him as a benefactor at arm’s length. The blocking in these films works in ways unconventional to the action genre. For one, fight scenes that place men and women on a platform of equal physical power work to foster egalitarianism. Andersen astutely proposes these fight scenes may even serve as a form of empowerment. Andersen also suggests, however, the possibility of action films as part of the often derided “body genre.” By Williams’s definition, this is a film that portrays some form of bodily excess at the behest of a victimized female. Although Kill Bill, Mad Max, Lady Vengeance, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo all feature forms of bodily excess— qua violence— and female victimization, they also work to portray men and women as equals, empower and de-victimize the women, and ultimately, subvert the male gaze. This subversion does not end at space and blocking, however. Our perceptions of these women are heavily influenced by not just the actions they perform, but the clothes they wear.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Film & Media |