Featured Article:Competing Claims in the South China Sea Viewed Through International Admiralty Law

By

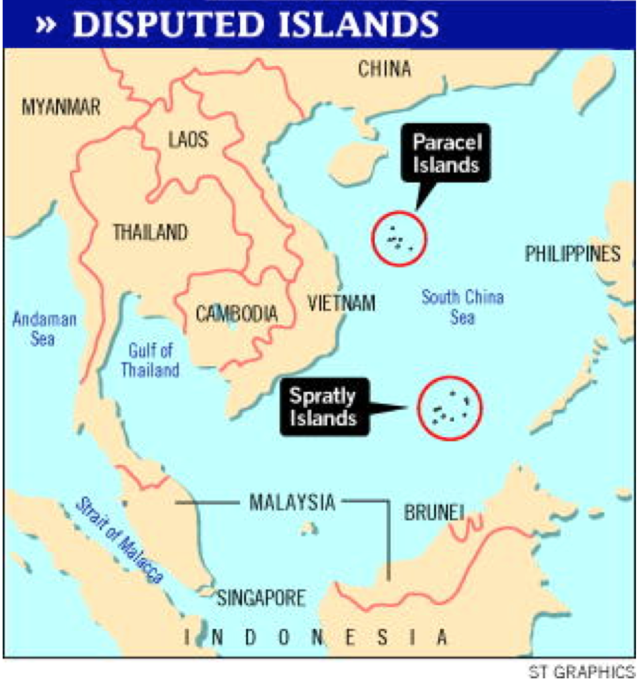

2016, Vol. 8 No. 01 | pg. 1/3 | » There is a longstanding territorial dispute raging in the South China Sea between China, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, Brunei, and Vietnam over several groups of islands called the Spratlys and Parcels. While most of the players involved are arguing over which islands belong to whom, China is claiming all of them as its territory. China’s so called “nine-dashed line” encompasses nearly all of the islands and labels over 90% of the South China Sea as part of the Exclusive Economic Zone of China. While the South China Sea dispute has a long and storied past, it is the present and future that pose the greatest difficulties to resolving the issue. Today, many of the islands are occupied by the disputants as they fight for control over the vast energy resources recently discovered below the seafloor. On top of that, advances in land reclamation technologies have enabled China to create and occupy many artificial islands throughout the South China Sea, thus changing the balance of power between the parties and changing the very layout of the area in dispute. This paper first explores the history of the dispute including the geography of the islands and the basis of the various states’ claims. Then, it explores the portions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea relevant to the dispute and analyzes how they impact the territorial claims being made. Finally, I explore the circumstances and possible outcomes of recent events affecting the dispute such as China’s creation of artificial islands, the United States’ newly announced freedom on navigation patrols, and the Philippines’s case against China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration. I. History of the DisputeA. Land Ho!The Spratly Islands sit in the eastern waters of the South China Sea, west of the Philippines and northwest of Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia.1 The island chain consists of “more than 140 islets, rocks, reefs, shoals, and sandbanks spread over an area of more than 410,000 square kilometers.”2 Some of the islands are totally submerged, some appear and disappear with the tides, and some are always above the sea.3 Less than forty of the Spratly Islands’ features are islands under Article 121(1) of UNCLOS, which defines an island as “a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.”4 All of the Spratly Islands are claimed by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam.5 Many of the features of the Spratly Islands also fall within the Kalayaan Island Group, claimed by the Philippines.6 Several features are also claimed by Malaysia, and one reef lies within 200 nm of Brunei Darussalam.7 More than sixty of the geographic features in the Spratlys are reportedly “occupied in some way by the claimants.”8 Itu Aba, the largest island and the only one with a fresh water source, is occupied by Taiwan.9 The other twelve largest islands are occupied by either Vietnam or the Philippines.10 Another report indicates that forty-four features are “occupied with installations and structures:”11 twelve of which are occupied by Vietnam, eight of which are occupied by the Philippines, seven of which are occupied by China, three of which are occupied by Malaysia, and one of which occupied by Taiwan.12 The Paracels consist of “about thirty-five islets, shoals, sandbanks, and reefs with approximately 15,000 km2 of ocean surface.”13 Woody Island, the largest island in the Paracels, is 2.1 km2, “which is about the same as the total area of the thirteen largest islands in the Spratly Islands.”14 Woody Island is the location of Sansha City, a prefecture-level city that China established in June 2012 as the administrative center for its claims in the South China Sea.15 B. China’s Large ClaimToday, China claims sovereignty over roughly 90% of the 3.5 million square mile South China Sea.16 In 1947, President Chiang Kai-shek's government first officially published an “eleven-dashed line” map to mark China's dominion in the South China Sea.17 This map was based on a supposedly historical claim dating back to ancient China. In a 2008 statement, senior diplomat, Zheng Zhenhua, told US officials that the nine-dashed line “indicates the sovereignty of China over the islands in the South China Sea since ancient times and demonstrates the long-standing claims and jurisdiction practice over the waters of the South China Sea.”18 Supporters of China's historic claim argue that China has maintained control of the islands within the area for “literally thousands of years. and that it was not until the last century that this control was contested.”19 Supporters state that control or sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea “began to manifest as early as the 21st century B.C. with the receipt of ‘tributes’ from that area.”20 Ancient historical documents that reference “trade records from the Zhou, Xia, and Shang Dynasties”21 are used as evidence that the South China Sea islands were “already destinations of Chinese expeditions and targets of conquest as early as 770 B.C.”22 According to international custom, a key element of a successful historical claim is “the extent to which other States accept or contest the claim.”23 Thus, any states who wish to contest the claim must take actions “commensurate with their stance--as inaction may be viewed as acquiescence to the claim.”24 China made its first legal claim to the South China Sea islands on September 9, 1958 in its Declaration on China’s Territorial Sea, piggy-backing off the declarations of other nations during the first codifications of the law of the sea.25 Thus, in this 1958 declaration, China affirmed its sovereignty over the “Pratas (Dongsha), Paracels (Xisha), Macclesfield Bank (Zhongsha), and Spratlys (Nansha).”26 The declaration stated:

The territorial claims as set out in this declaration have remained relatively stable up to the present day and have been reasserted on several occasions.28 On February 25, 1992, China promulgated its Law on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. Article 2 of this declaration states:

China also reaffirmed its claims when it ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1996, by making express reference to its 1992 law.30 In two notes verbales filed in 2009 and one filed on April 14, 2011China reaffirmed its territorial pretensions in an even broader fashion, stating that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters.”31 II. The Law And The South China SeaA. UNCLOS ProvisionsThe United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), is the international agreement that resulted from the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, which took place between 1973 and 1982.32 The Law of the Sea Convention “defines the rights and responsibilities of nations with respect to their use of the world's oceans, establishing guidelines for businesses, the environment, and the management of marine natural resources.”33 After nearly ten years of work and development, UNCLOS proved to be far more comprehensive than any previous attempt at creating a regulatory regime for the seas.34 What makes UNCLOS unique is that it “addresses the limits of State sovereignty in coastal waters and navigational regimes within those limits by establishing measurable boundaries for such activities,”35 and “strikes a balance between the rights and duties of coastal States on the one hand, and of all other States on the other.”36 The UNCLOS creates “distinct and shared functional areas” such as the “territorial sea, the contiguous zone and the EEZ.”37 Beginning with the coastal baseline, “each [zone] incorporates its smaller-in-size contemporary”38 and interconnects such that none can exist without the others.39 Under UNCLOS, the first twelve nautical miles out from a state’s coastal baseline are considered territorial waters.40 In territorial waters, a state has full sovereignty over the airspace, sea, and resources.41 After that, states may establish a contiguous zone that extends (at most) another twelve nautical miles in which they may exercise whatever control necessary to “prevent infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea” or “punish infringement of the…laws and regulations committed within its territory or territorial sea.”42 Finally, after the contiguous zone, states may establish an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) which extends 200 nautical miles from the baseline.43 Within its EEZ, states have:

As the largest of the established areas, the EEZ “provides coastal States with enormous economic opportunity.”45 While coastal states are able to exploit the resources within their EEZ, other states are still able to navigate freely through an EEZ and even engage in certain commercial activities within a state’s EEZ. 46Throughout the negotiations leading to UNCLOS “the consensus developed that non-resource-related high seas freedoms, including the freedoms of navigation and overflight, and the freedoms to lay pipelines and submarine cables would be preserved in the EEZ.”47 B. The Competing ClaimsMalaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam “view the South China Sea through the lens of international law, especially UNCLOS.”48 Brunei's claim in the South China Sea is limited to its Exclusive Economic Zone (“EEZ”), “which extends to one of the southern reefs of the Spratly Islands.”49 Malaysia's claim is limited to the boundaries of its EEZ and continental shelf.50 Malaysia occupies five islands of the Spratlys, “including Layang Layang Island/Danwan Jiao (Swallow Reef) where a scuba diving resort is built.”51 The Philippines claims ownership of “more than 50 land features of the Spratly Islands, known as the Kalayaan island group (“KIG”), but occupies only nine of them.”52 Taiwan, like China, “claims all of the Spratly Islands, but only occupies Itu Aba (Taiping Dao), the largest of the Spratly archipelago.”53 In 1974 and 1988, respectively, armed conflicts at sea broke out between China and Vietnam over the ownership of the Paracel and Spratly Islands.54 Since 1974, the Paracel Islands have been under the effective control of China, but contested by Vietnam and Taiwan.55 The nations involved in this dispute have, on many occasions sought recognition of their claims by the UN itself and their neighbors. Many states involved have submitted requests to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to extend their EEZs past 200 nm. Coastal coastal states intending to establish the outer limits to their continental shelves beyond 200 nm “are required to submit particulars of such limits to the CLCS within ten years of the entry into force of UNCLOS.”56 On May 6, 2009, Malaysia and Vietnam made a joint submission to the CLCS with respect to their claims in the southern part of the South China Sea.57 Their submission claimed an extended EEZ for each country which included some of the islands north of Borneo that are also claimed by the Philippines.58 China and the Philippines each filed an objection to the Joint Submission. China objected on the grounds that it holds “indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea,”59 and the Philippines objected because such an extension would create an overlap between their EEZs.60 In a vicious cycle, the unanswered questions of who controls what and where fuel these territorial disputes which, in turn, raise more and more questions about the parties’ rights under our current legal regime. In the end, these unanswered questions leave us with overlapping claims which, when viewed on a map, border on absurdity. Image source: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-06/kerry-says-us-will-not-accept-restrictions-in-south-china-sea/6679060 C. Definitions MatterOne of the main questions fueling the controversy is a definitional one. Are these islands actually “islands” under UNCLOS, and, if they are something else, what kind of zones do they get? UNCLOS makes important distinctions between “offshore geographic features such as (1) islands, (2) rocks, (3) low-tide elevations, (4) artificial islands, installations, and structures, and (5) submerged features.”61 This is significant because not all features defined in UNCLOS are entitled to contiguous zones or EEZs. Article 121(1) of UNCLOS defines an island as a “naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.”62 Generally, islands are entitled to the same maritime zones as a state’s land territory (territorial waters, contiguous zone, and EEZ) which are measured from the low water line along the coast as the baseline.63 There is an important exception to this rule. Article 121(3) states that rocks that “cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no EEZ or continental shelf.”64 In other words, “they are entitled only to a territorial sea and contiguous zone.”65 Low-tide elevations are naturally formed areas of land surrounded by and above water at low tide, but submerged at high tide.66 They are not islands and are “not entitled to any maritime zones of their own.”67 If they are within 12 nm of any land territory, however, including an island, “they can be used as part of the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.”68 The ICJ elaborated on questions surrounding low-tide elevations in the 2001 case Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Qatar and Bahrain.69 The court concluded that “it is not established that low-tide elevations can, from the viewpoint of acquiring sovereignty, be fully assimilated to islands or other land territory.”70 Finally, the Court stated that a low-tide elevation that is situated beyond the limits of the territorial sea “does not have a territorial sea of its own and, as such, does not generate the same rights as islands or other territory.”71 Finally, artificial islands and structures are manmade features in the water (e.g. permanent platforms), or new land formations created using land reclamation technologies. Under UNCLOS, these structures are not islands; “they have no territorial sea of their own, and their presence does not affect the delimitation of the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone, or the continental shelf.”72 Within their EEZs, coastal states have the exclusive right to construct such artificial islands or structures and have jurisdiction over them.73 It is estimated that “less than forty of the features in the Spratly Islands meet UNCLOS's definition of an ‘island.’”74 Applying the rules and definitions of UCLOS to the South China Sea raises many important questions. First, how many of the features are islands because they are naturally formed areas of land surrounded by water but rest above the water at high tide?75 Second, how many of the islands are entitled “only to a territorial sea and contiguous zone because they are rocks that cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own?”76 Third, how many of the islands can sustain human habitation or economic life?77 Many of the features in the South China Sea are completely submerged, even at low tide. They are not islands, “are not capable of a claim to sovereignty,” and cannot generate any maritime zones.78 Also, “it seems reasonable to conclude that the tiny uninhabited rocks on Scarborough Shoal are rocks that cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own,” and thus would only be entitled to a territorial sea and contiguous zone.79 Woody Island, the largest island in the Paracel Islands, is an island that is likely “entitled to an EEZ and continental shelf of its own,” but, for many other features, “there is likely to be no consensus.”80 None of the claimants in the South China Sea have clarified which features they consider to be islands, rocks, low-tide elevations, artificial islands, and so on.81 The resulting uncertainty is noteworthy since “the majority of features are not above water at high tide.”82 Furthermore, there are cases in which “a claimant state has built installations and structures on low-tide elevations or submerged features within 200 nm of another claimant.”83 The claimant states have also not clarified which features they believe are islands, nor have they clarified what maritime zones they are entitled to claim from such islands.84 The uncertain status of so many features in the South China Sea, coupled with the speed at which more are added via land reclamation technology makes an already complicated situation even more difficult to analyze.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |