From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 9 NO. 1The New Silk Road: Assessing Prospects for "Win-Win" Cooperation in Central Asia

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2016, Vol. 9 No. 1 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

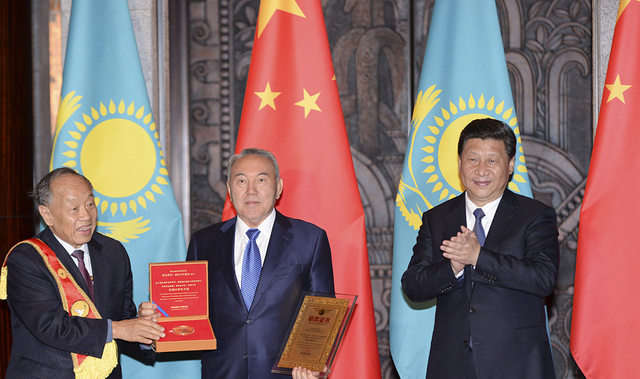

IntroductionThe New Silk Road, formally termed the Silk Road Economic Belt and also known as the "One Belt, One Road," was first proposed by China's President Xi Jinping during his 2013 visit to Central Asia. This initiative aims to revive the historical vitality of trade and exchanges among Central Asian countries and China.1 The vision of the Economic Belt "[brings] together China, Central Asia, Russia and Europe (the Baltic); linking China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and the Indian Ocean."2 In Central Asia, the New Silk Road is designed to pass through Khorgos, Almaty, Bishkek, Dushanbe, Samarkand, and Turkmenistan before reaching Tehran. The New Silk Road is the landmark initiative of China's economic engagement in Central Asia, serving to meet China's economic needs of developing its western provinces such as Xinjiang and gaining access to energy resources in Central Asia. However, China's efforts at engagement are set to compete directly with those of Russia. Central Asia has traditionally belonged to Russia's sphere of influence. Starting from the 2000s, Russia has started to reengage with Central Asia with the goal of playing "a dominant or privileged role" in the region.3 China's increased economic presence in Central Asia may conflict with Russian initiatives to reinstate its prominent regional role, most notably through the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). As Chinese and Russian engagement in the region continues to intensify, it is inevitable that they will vie for the Central Asian countries' attention and resources. However, interactions between China and Russia in Central Asia are not necessarily zero-sum due to the vast size and potential of the economic market within the RussiaCentral Asia-China triangle. This paper argues that the coexistence of the New Silk Road with the EEU is feasible, and that potential exists for China and Russia's "winwin" cooperation in Central Asia. It provides evidence for this claim through examination of the New Silk Road's bilateral and multilateral cooperation mechanisms, with a focus on the areas of infrastructure and trade, and evaluating China's overall economic and diplomatic strategy toward the region.The New Silk RoadFrom its inception, the New Silk Road was a strategic concept to be realized through "bilateral and multilateral cooperation mechanisms," not an initiative driven solely by China.4 The white paper issued jointly by China's National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Commerce, stresses cooperation as the mechanism to achieve strategic goals. It states, "The Belt and Road Initiative is a systematic project, which should be jointly built through consultation to meet the interests of all."5 More specifically, the white paper mentions several multilateral organizations in which Central Asian countries participate in some form and whose functions align with the strategic vision and objectives of the New Silk Road initiative. The New Silk Road spans across many of the region's countries, providing incredibly enhanced opportunities for trade and cooperation. In the transportation sector, a key regional multilateral organization is the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC), which plays an important role in achieving "road connectivity," a basic component of the New Silk Road.6 Formed by 10 member countries in the greater Central Asian region, including China, CAREC has been working on regional cross-border transportation development long before the New Silk Road initiative was established. With regard to road building, CAREC's Transport and Trade Facilitation Strategy identified six transport corridors as the organization's "flagship initiative."7 Many older transportation corridors in Central Asia are oriented north toward Russia, not east toward China. However, since 2001 CAREC has invested approximately $28.3 billion in developing these corridors, three of which lead to China.8 For example, within CAREC Corridor 1, the Urumqi-Kashgar road connects Xinjiang to Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and the Russian Federation.9 CAREC Corridor 2 links Kazakhstan with China, Russia and western seaports, including Aktau, a port on the Caspian Sea that transports goods to Europe and Asia.10 In CAREC Corridor 5, a toll expressway connects Xinjiang to Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Pakistan, and Tajikistan.11 Energy pipelines, another major component of regional infrastructure development, have been developed primarily through bilateral efforts. China's main pipeline project in Central Asia is the Central Asia-China Gas pipeline. On the basis of bilateral agreements between China and other involved countries, Line A, Line B and Line C have already been completed, running parallel from the Turkmen-Uzbek border through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan before reaching Xinjiang.12 In September 2013, China signed bilateral agreements with Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan to commence plans for Line D. These state-to-state agreements were followed by agreements between China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and its Central Asian counterparts, such as Tajiktransgaz and Uzbekneftegaz, to establish joint ventures and manage the construction and operation of Line D.13 Upon Line D's estimated completion in 2016 the annual transmission capacity of the entire Central Asia-China pipeline will reach 85 billion cubic meters, making it "the largest gas transmission system in Central Asia."14 Other major joint projects have been developed between China and Central Asian countries, such as the gas field development in Amu Darya in Turkmenistan.15 Improved infrastructure constructed through multilateral and bilateral efforts advanced by the New Silk Road initiative is critical to facilitate trade. CAREC's transport corridors aim to facilitate 5 percent of all Europe-East Asia trade by 2017, which will significantly increase the income of the transit countries.16 Oil pipelines built through bilateral efforts also boost trade. The Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline, which is part of the Central AsiaChina Gas pipeline network, will transport 55 billion cubic meters of gas annually to China by the end of 2015, approximately 20 percent of China's annual natural gas consumption.17 In addition to trade gains reaped through joint infrastructure construction, Central Asian countries and China are also collaborating to improve regional trade policies. Beyond the formal economic relationships between China and Central Asia, informal trade or "shuttle trade" among countries in the region is substantial but often overlooked.18 Chinese consumer goods are brought into the region through Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic without full declaration at border customs, and the individual traders who transport them take advantage of arbitrage to earn profit.19 The New Silk Road initiative will deepen China's cooperation with Central Asian countries to improve border control and reduce entry barriers, so that informal trade will be directed into formal channels, and countries will reap tax, customs and security benefits.20 Cross-Border Transport Agreements have already been signed between countries such as Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic.21 In the Kyrgyz Republic, freight associations also monitoring travel and waiting times so that border crossing and the transnational shipment of goods can be improved.22 The New Silk Road initiative will deepen China's cooperation with Central Asian countries to improve border control and reduce entry barriers, so that informal trade will be directed into formal channels, and countries will reap tax, customs and security benefits. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a multilateral organization focused on regional security, will also play a greater role in the New Silk Road initiative. Member states of the SCO include China, Russia and four Central Asian states, who are involved in the SCO Business Council and the SCO Interbank Consortium to work on multilateral financial and economic projects. At the SCO Summit in July this year, the Russian and Chinese leaders agreed to consider SCO as "a convenient floor for integrating the implementation of [the New Silk Road and the EEU]."23 Both countries voiced support for joint infrastructure development and financing development in the region, calling for a common SCO transport system that incorporates and enlarges the volume of existing transport systems such as Russia's Trans-Siberian and Baikal-Amur railways.24 The SCO will facilitate China's economic engagement in Central Asia and advance the goals of the New Silk Road. China's "Win-Win" StrategyAlthough China is entering Russia's traditional sphere of geopolitical influence and deepening its economic presence in Central Asia, Russia's official reactions have been largely mild. One key reason for this is that China offers Russia a substantial piece of its domestic energy market, thus achieving a "win-win" in this area. According to British Petroleum data, Russia produced 12.9 percent of the world's total production of oil in 2013.25 China (including Hong Kong), on the other hand, was responsible for 12.5 percent of world total oil consumption.26 As the world's largest energy consumer and still a fast-growing emerging economy, China seems to have few problems offering energy contracts to both Russia and Central Asian countries. As Jane Nakano and Edward C. Chow of the Center for Strategic and International Studies observe, China and Russia have grounds for mutual benefit in the energy sector. China needs to expand its energy imports to meet domestic demand and improve its environment, while Russia needs to diversify exports in its natural gas market and sustain its economy.27 Revenue from energy exports comprises over 70 percent of Russia's total export revenues; however, this revenue has been jeopardized by Russia's economic crisis and the fall of oil prices.28 Due to these complementary needs, a score of bilateral energy deals were signed in 2014. In May 2014, China and Russia concluded a landmark $400 billion natural gas supply contract. Gazprom and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed a deal on supplying 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year from West Siberia to China, starting from 2018.29 Also, Russia's Novatek is to supply at least 3 million tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to China, and Rosneft will double its oil supplies to China.30 Russia has even allowed CNPC to take a 20 percent stake in Novatek's project and a 49 percent stake in Rosneft's oil development project in East Siberia, "rare moves of the Russian energy sector" since Russia doesn't usually invite foreign investment in this industry.31 With the European market stagnant and the European Union imposing economic sanctions on Russia, it is in Russia's interest to expand its energy exports to Asia, starting from China, its closest Asian Pacific neighbor. Indeed, Russia's energy strategy to 2035, released in 2014, forecasts that "23 percent of all energy exports will be sent to the Asia-Pacific region by 2035," up from the 6 percent it currently exports to the Asia-Pacific.32 Unlike Russia, however, Central Asian nations cannot match China's geographical size, international status, economic power and political clout. For these countries then, economic relationships with China present both an opportunity and a dilemma. While China is eager to expand trade and build infrastructure in Central Asia, Chinese imports from Central Asia remain mostly raw materials, and Chinese infrastructure projects often involve Chinese companies that employ more Chinese workers than locals.33 For example, while Kazakhstan exports metals and crude oil to China, China exports clothing, electronics and household appliances to Kazakhstan.34 The imbalance in both trade volumes and content between China and Central Asian countries risks fueling public discontent and social tension, as demonstrated by protests against leasing farmland to Chinese farmers in Almaty, Kazakhstan, in 2010.35 While such issues should be recognized and resolved either through short-term policy corrections or long-term economic development, they should not overshadow the fact that "winwin" economic opportunities for China and Central Asian countries do exist. Central Asian countries can employ the New Silk Road to diversify their trading partners and revive their importance in "trans-continental transit trade" as goods are routed "through the reemerging East-West and North-South trade routes."36 President Nazarbayev and President Xi Jinping, pictured center and right, at a talk before Xi Jinping accepted a peace prize for his New Silk Road vision. Infrastructure development advanced by the New Silk Road initiative is a "win-win" because it diversifies and enlarges trade opportunities for both China and Central Asian countries. CAREC Corridor 1 is "an important transit route for cargo" from China, Kazakhstan, Russia, and European countries that will generate significant revenue in transit fees for the countries it traverses.37 The KorlaKuqa expressway, part of CAREC Corridor 5, connects "improved rural roads to schools, hospitals, and markets for about 50,000 rural people," facilitating the expansion of trade.38 With regard to oil and gas, the most important product in China's trade with Central Asia, it is as much in Central Asian countries' interest to diversify their energy exports as it is in China's interest to import from them. When in 1998 Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin cut off the export of gas from Turkmenistan, it reminded the country that trade diversification was indispensable for economic security.39 For Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, the two states in Central Asia with more politically autonomous relationships with Russia, China has become an increasingly important trading partner. For instance, 60 percent of Uzbekistan's energy resources now flow to China.40 Coexistence between the New Silk Road and EEUThe Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) aims to become a powerful economic union that will accumulate "natural resources, capital, and strong human potential" in the region to become a competitive regional bloc in the international economy.41 Currently, the EEU has five members: Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. Together, the EEU members produce a GDP of $2,411.2 billion and are the top natural gas producers in the world.42 The common understanding among its members is that the EEU seeks to deepen regional economic integration, with its first and foremost goal to create "common markets of electric power, gas, oil and petroleum products."43 A common market of labor" is the intended next step—an ecnomic boost for member countries whose national income relies substantially on remittances.44 Tajikistan needs Russia as a market to export labor.47 At the same time, Tajikistan is worried about limitations on its trade with non-EEU countries and constraints on its foreign policy. The recent accession of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan into the EEU occurred amid domestic opposition and doubt. Their concerns, shared by other Central Asian countries, derived from the potential risks of accession to the EEU: losing economic gains in trade with non-EEU countries and losing political influence in sovereign affairs to Russia. Kyrgyzstan is currently a key re-exporter of Chinese goods, in which it imports goods from China on a low customs fee scheme and makes profit by selling these goods to Kazakhstan and Russia, where customs fees on goods from China are higher. However, the EEU's new import tariff for goods originating outside the EEU is higher than Kyrgyzstan's current tariff regime and might cause Kyrgyzstan to lose its profitable position in this trade.45 Tajikistan, the next likely candidate for membership in the EEU, has similar concerns. The majority of Tajiks favor joining the Union in hopes of less restrictions on their ability to work in Russia.46 With its working-age population rapidly growing and domestic job growth unable to keep pace, Tajikistan needs Russia as a market to export labor.47 At the same time, Tajikistan is worried about limitations on its trade with non-EEU countries and constraints on its foreign policy. Higher and less uniform tariffs within the Union would result in more expensive imports from nonEEU member countries.48 Smuggling from border countries will be reduced due to tightened security, and the volume of Chinese goods available for re-export will decrease.49 Central Asian countries are also apprehensive about Russia's political motives for economic integration. In 2014, Russia supplied 61.9 percent of the volume of goods in the EEU market, while Belarus supplied 29 percent, and Kazakhstan supplied a mere 9.1 percent.50 Russia's economic clout could easily translate into political leverage within the economic union. Comparison with the development of the European Economic Community and the Eurasian Economic Union also suggests the possibility of further political integration. EEU institutions, such as the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council and the Eurasian Economic Commission, are modeled after those of the European Union.51 It seems inevitable that political considerations will come into play as Russia "coordinates" policy for the ends of achieving "common markets" in the Union.52 For one, Moscow's threats of reducing migrant worker quotas would be an effective way of pressuring other EEU members. For another the EEU should in principle "apply a common external trade policy in all respects to third countries," and Russia's counter-sanctions against Europe are also imposed on other EEU countries, which affects their economic growth and displays Russia's tendency of aligning other countries' economic interests with its own to meet political objectives.53 Such action has already provoked reaction from Belarus and Kazakhstan, who are not complying with these counter-sanctions and continue to purchase banned European goods.54 In contrast, China's New Silk Road initiative is an economic agenda and does not even remotely resemble a political union. As this paper has discussed, China's initiative relies on bilateral and multilateral mechanisms, some already existing, for developing infrastructure and trade in Central Asia. The New Silk Road "centers" its approach to regional integration on economic cooperation and "economic facilitation."55 Its main components as identified by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are policy communication, road connectivity, trade, monetary circulation and people-to-people exchange.56 These components all serve the overarching goal of facilitating economic growth. China also takes extra care to stick to its economic agenda and avoids interfering with domestic politics in the region. For example, it has held off from investing in the Rogun Dam until Tajikistan and Uzbekistan resolve their disputes over the project.57 Using David Arase's phrase, the aim of the Silk Road Initiative is "to channel economic flows to or from China."58 Expanding trade with China enables Central Asian countries to balance against Russia's economic power, which also curbs Russia's political leverage on them. ConclusionThis paper has argued that the New Silk Road initiative offers great potential for "winwin" cooperation in Central Asia, between China, Russia and Central Asian countries. For Central Asian countries, an economic relationship with both Russia and China is double insurance. Expanding trade with China enables Central Asian countries to balance against Russia's economic power, which also curbs Russia's political leverage on them.59 According to Nate Schenkkan of Freedom House, Central Asian countries are especially vulnerable to low oil and gas prices, ruble depreciation, remittance income from migrant workers in Russia, and Russian investment and contracts for infrastructure.60 Deeper energy and economic ties with China serve to boost growth when the Russian option is yielding weak results, such as during Russia's current economic crisis beginning in 2014. At the same time, maintaining trade ties with Russia guards against China's potential "economic imperialism,"61 with negative consequences for economic dependency and the environment. Central Asian countries can balance both Russia and China to ameliorate the negative effects of going over completely to one side and cutting ties with the other. China and Russia...must choose whether to compete or cooperate while pursuing their goals in Central Asia. With regard to the relationship between China and Russia, they must choose whether to compete or cooperate while pursuing their goals in Central Asia. Cooperation is the more pragmatic and likely choice. Indeed, China and Russia have already begun to take concrete steps to cooperate. In May 2015, China and Russia agreed to "set up a dialogue mechanism for the integration" of their strategic initiatives towards the region.61 As Andrew Scobell, Ely Ratner and Michael Beckley of the RAND Corporation point out, China's influence in Central Asia "remains quite modest except in the economic realm," and China is unlikely to impede Russia's political ambitions in the region in the foreseeable future.62 The two countries are courting the same Central Asian countries with a shared aim of regional economic growth. Joint development of infrastructure projects would give Russia access to China's deep investment pockets for improving connectivity in Central Asia, and a joint customs space would cut costs for Chinese goods going to the European Union through the EEU.63 By advancing regional infrastructure development and trade, the New Silk Road may prove a new engine for realizing "win-win" cooperation among all players in the region. ReferencesAnishchuk, Alexei. "As Putin looks east, China and Russia sign $400-billion gas deal," Reuters, May 21, 2014. Accessed November 4, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/05/21/us-china-russia-gas-idUSBREA4K07K20140521#QojSrt3TrQrg2uWD.99 Arase, David. "China's Two Silk Roads: Implications for Southeast Asia." ISEAS Perspective 2 (January 2015). Accessed May 3, 2015. http://www.iseas.edu.sg/documents/publication/ISEAS_perspective_2015_02.pdf. Asian Development Bank. "The New Silk Road: Ten Years of the Central Asia Economic Cooperation Program." Accessed April 20, 2015. http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29389/new-silk-road.pdf. British Petroleum. "BP Statistical Review of World Energy." Accessed May 9, 2015. https://www.bp.com/content/ dam/bp/pdf/Energy-economics/statistical-review-2014/BP-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2014-full-report.pdf. Bryd, William and Raiser, Martin. "Economic Cooperation in the Wider Central Asia Region." World Bank. Accessed April 20, 2015. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSOUTHASIA/556101-1101747511943/21363080/WiderCAWorkingPaperfinal.pdf. CAREC. Accessed April 15, 2015. http://www.carecprogram.org/. CNPC. "Flow of natural gas from Central Asia." Accessed April 22, 2015. http://www.cnpc.com.cn/en/FlowofnaturalgasfromCentralAsia/FlowofnaturalgasfromCentralAsia2.shtml. Cooley, Alexander. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford Scholarship Online: 2012. Dutkiewicz, Piotr, and Sakwa, Richard. Eurasian Integration The View from Within. New York: Routledge, 2015. Eurasian Commission. "Eurasia Economic Integration: Facts and Figures." Accessed May 8, 2015. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/en/Documents/broshura26_ENGL_2014.pdf. Fedorenko, Vladimir. "The New Silk Road Initiative in Central Asia," Rethink Institute, Working paper 10. Accessed May 8, 2015. http://www.rethinkinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Fedorenko-The-New-Silk-Road.pdf. FMPRC. "President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries." Accessed April 22, 2015. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpfwzysiesgjtfhshzzfh_665686/t1076334.shtml. Jiang, Xuan. "Zhongshiyou jiang yu wu jianli hezi gongsi yunying zhongyatianranqiguandaoDxian." Yicai, August 21, 2014. Accessed November 4, 2015. http://www.yicai.com/news/2014/08/4010424.html Kucera, Joshua. "China's relations in the Asia-Pacific: Central Asia." The Diplomat, February 2011. Accessed April 23, 2015. http://thediplomat.com/2011/02/central-asia/. Nakano, Jane and Chow, Edward C. "Russia-China Natural Gas Agreement Crosses the Finish Line." CSIS, May 28, 2014. Accessed May 8, 2015. http://csis.org/publication/russia-china-natural-gas-agreement-crosses-finishline. Olimova, Saodat. "Tajikistan's Prospects of Joining the Eurasian Economic Union." Russia Analytical Digest 165 (March 17 2015): 13-16. Peyrouse, Sebastien. "Impact of the Economic Crisis in Russia on Central Asia." Russia Analytical Digest 165 (March 17 2015): 3-6. Rickleton, Chris. "Turkmenistan: Seeking New Markets to Check Dependency on China." Eurasianet, November 6, 2014. Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.eurasianet.org/node/70801. Scobell, Andrew, Ratner, Ely, and Beckley, Michael. "China's Strategy Toward South and Central Asia: An Empty Fortress." Rand Corporation, 2014. Accessed May 9, 2015. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR500/RR525/RAND_RR525.pdf. Starr, Frederick S., and Cornell, Svante E., eds. Putin's Grand Strategy: The Eurasian Union and Its Discontents. Central Asia Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program: 2007. Accessed April 25, 2015. http://www.silkroadstudies.org/publications/silkroad-papers-and-monographs/item/13053-putins-grand-strategy-the-eurasianunionand-its-discontents.html. Tarr, David G. "The Eurasian Economic Union among Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and the Kyrgyz Republic: Can it succeed where its predecessor failed?," The Graduate Program in Economic Development, Vanderbilt University, September 29, 2015. Accessed November 4, 2015. http://as.vanderbilt.edu/gped/documents/DavidTarrEurasianCustomsUnion-prospectsSept282015.pdf. Tass Russian News Agency. "Putin and Xi Jinping discuss projects to combine the Silk Road economic belt with EEU." Tass Russian News Agency, July 8, 2015. Accessed October 24, 2015. http://tass.ru/en/economy/806984. The BRICS Post. "China's Silk Road wins big at SCO Summit," The BRICS Post, July 11, 2015. Accessed October 24, 2015. http://thebricspost.com/chinas-silk-road-wins-big-at-sco-summit/#.Vi6mpGSrQy4. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). "Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road." Accessed April 20, 2015. http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/201503/t20150330_669367.html. Tian, Shaohui, ed. "China, Russia agree to integrate Belt initiative with EAEU construction," Xinhua News Agency, May 9, 2015. Accessed May 9, 2015. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-05/09/c_134222936.htm. U.S. Department of State. "Investment Climate Statements 2014: Kyrgyz Republic." Accessed May 9, 2015. http://www.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/2014/index.htm. References

Image Attributions Public Domain Xizhuxi.jpg 2014 [Public Domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Xizhuxi.jpg)], via Wikimedia Commons. By Canuckguy (JCRules derivative) Eurasian Economic Union.svg 2014[Public Domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eurasian_Economic_Union.svg)], via Wikimedia Commons. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Political Science |